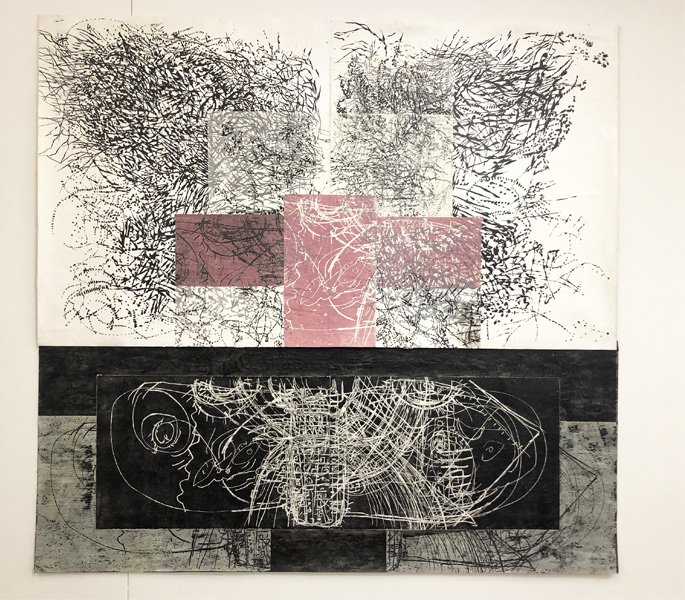

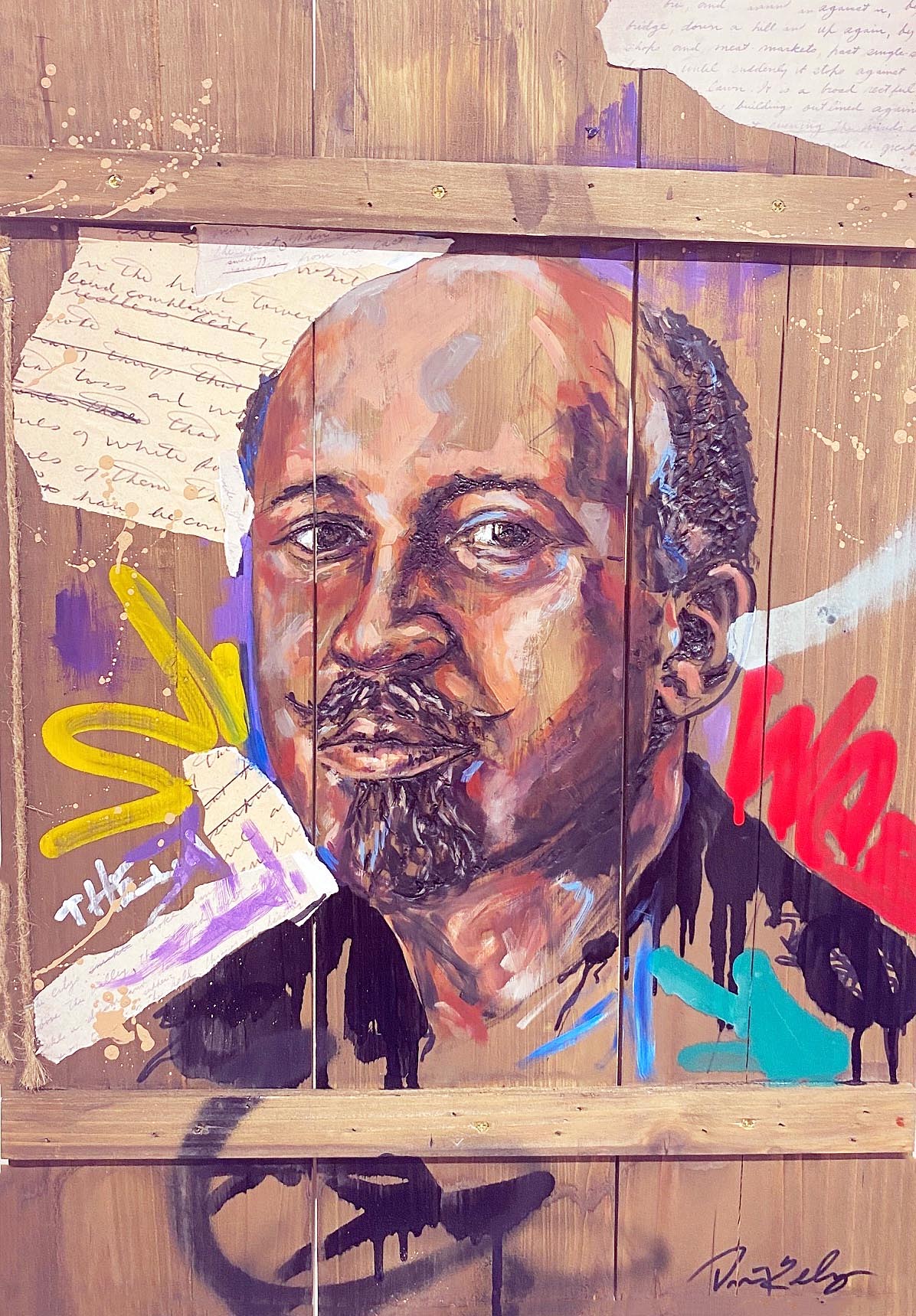

Installment Image, Souls Of Black Folk, Scarab Club, Detroit, Images : Courtesy of David E. Rudolph/ D. Ericson & Associates Public Relations.

In W.E.B. DuBois’ essay, “Of Our Spiritual Strivings” from his poignant collection, The Souls of Black Folk, the sociologist makes a thorough and thought triggering assessment on being Black in America.

“The Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world, — a world which yields him no self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world,” he wrote. “It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness; an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

Written in 1903, this passage is the impetus for the exhibition Souls of Black Folk: Bearing Our Truths, on view at the Scarab Club through March 20. Curated by Donna Jackson, artist and owner of DMJ Studios, DuBois’ words and concept of dual identity – being Black and being American– resonated on a deeper and heightened level for Jackson throughout 2020 – a year imploded with a global health pandemic that still looms and a socio-political and racial reckoning that forced America to finally discuss racism and injustices on a worldwide stage.

In a reflective statement about the exhibition, Jackson expressed, “With the death of George Floyd and the amount of pain and in many cases, guilt I have seen poured in our streets and in our media, I went back and re-read The Souls of Black Folk. The two-ness of being Black and American sits heavy and true with me. Sometimes this feeling is hard to pinpoint or express and yet, DuBois did it simply. It freed me to know that this feeling can be described. It is okay to be these two things. To be Black. To be American. The challenge is being accepted as both.”

The collection features the works of twenty, established and emerging Black artists – a first in the Scarab Club’s 100+ year-history– and range in emotion from depictions of harsh truths of existence in a Black body as well as expressions of joy, love and being human.

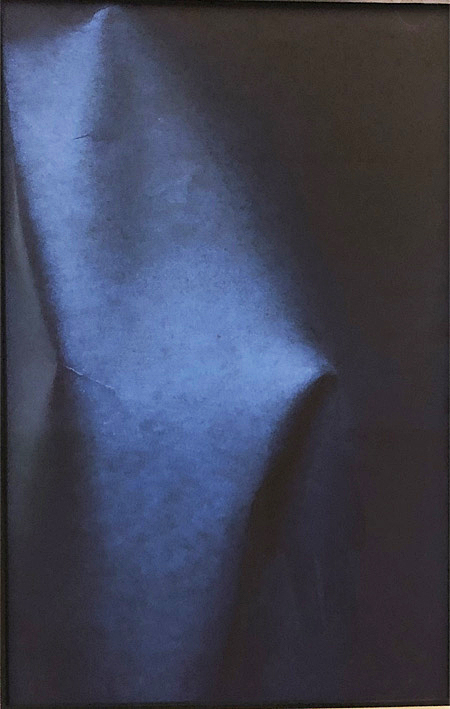

Jackson’s Black and Blue, sets a strong tone. The massive acrylic painting depicts a faceless black body as a shooting target, a red dot is on the chest and the words black and blue are scribbled throughout. ‘Black Lives Matters’ and ‘Blue Lives Matter’ chants mentally collide, drawing flashes of the racial contention and shooting deaths of Black men and women by police officers and white citizens. I am reminded of Dubois’ use of the veil as a metaphorical presentation of the color line, racial oppression and injustices.

Donna Jackson| Black and Blue (Who’s The Target) | Acrylic on Canvas

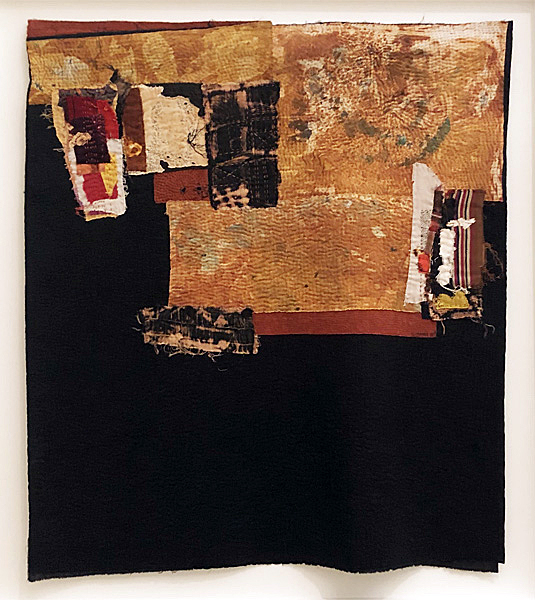

There’s a trauma that exists within Blackness that is inexperienced in mainstream America. Yvette Rock’s The Brutal Passage depicts the foundation of that pain. Accompanied by a performance, entitled 400 Years of Labor, the magnitude of the mixed-media canvas is aptly felt. Before the artist appears on screen, chains clinking is the first sound, followed by foot thumps, groans and heavy breathing. The artist appears carrying the thick canvas, each step a struggle. Each step a reminder of slavery and the oppressive mentality behind it.

The emotional and psychological grief that comes with injustice and trauma carries over into Carole Morriseau’s chilling, The Healing Wall. The mixed-media ensemble comprises four quadrants, containing 1200-1500 colorful ribbons with painted portraits bearing the names of Black lives lost due to police brutality. George Floyd. Rodney King. Breonna Taylor. Ayanna Jones. Emmett Till. And the list of Black and brown souls, gone (as we see it) too soon, goes on. Morriseau also incorporates phrases #StopTheKillings and #IAmTrayvon to represent social justice movements. The visual breaks your heart, but there is also a source of strength, purpose and a knowing that this is why we must continue to lift their names and use the tears as fuel to keep marching forward in hopes of a just world.

Yvette Rock | The Brutal Passage | Mixed Media on Canvas| 72×36| 2020

Carole Morriseau | The Healing Wall | Mixed Media | 45×50| 2020

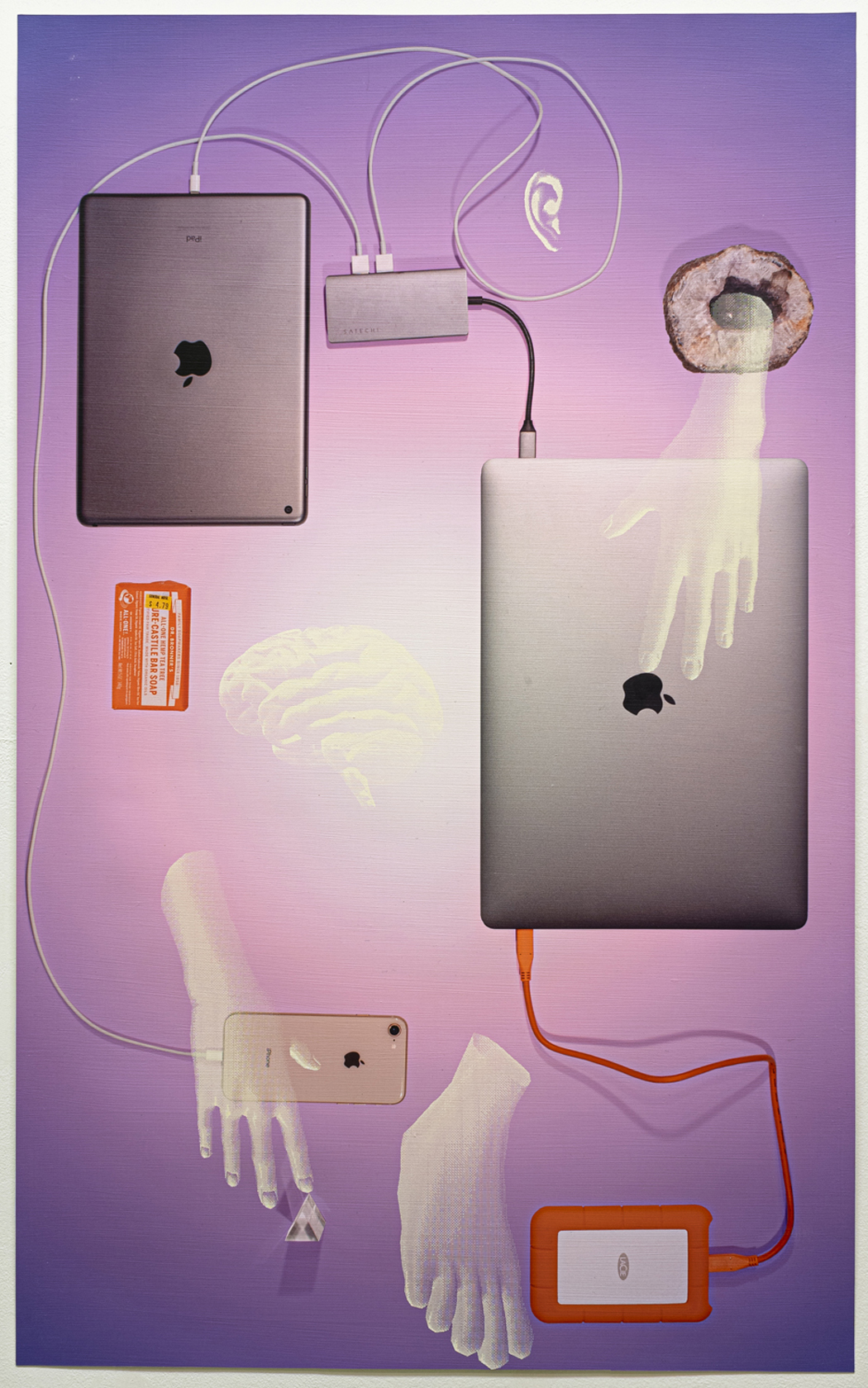

Grief is heavily felt in the aforementioned pieces and in Rita Dickerson’s$100,000,000 SLAVES: The Absence of Black Ownership and Control, that never settles. In this assortment of feelings, there is a visceral balance and resilience presented in the installation. We see the way joy claims its right to shine in spite of historical pain and constant wearing of the veil in Cydney Camp’s Juneteenth (Teenth) painting, which depicts a couple laid out in a yard, smiling while taking in a hot day, and Ralph Jones’ life photo, We’re All Here, that shows Black and brown children and families playing in water at Hart Plaza, and certainly in Mandisa Smith’s Black Joy made from felted wool. This is part of the story, too. This is love and care.

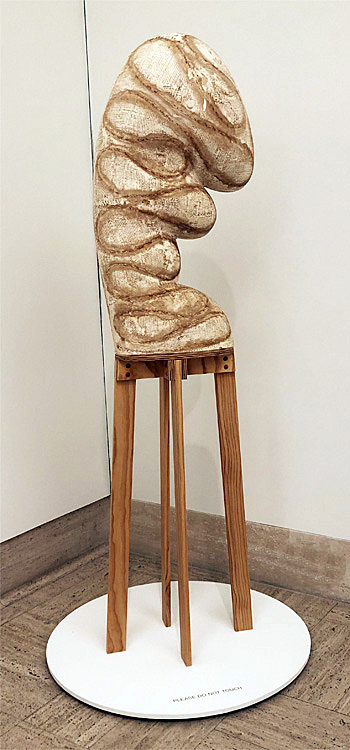

Mandisa Smith | Black Joy | Mixed Media | 18inx18in | 2020

Honoring the ancestral realm with spiritual grounding and understanding “I am, because they are,” Monica Brown’s mixed-media-on-wood painting and image-making, I Prayed For You Before You Were Born (I) and Prayed For You Before You Were Born (II ), are soothing like a needed hug. The art works are part of the artist’s ‘Mythical Memory’ series rooted in connections between the body, memory, personal history and healing. The circular motion in these small but mighty visuals feels like a continuous prayer and donning of armor by loved ones.

Monica Brown | I Prayed For You Before You Were Born (I) | Acrylic and Mixed-Media on Wood | 8”x8”

Monica Brown | I Prayed For You Before You Were Born (II) | Acrylic and Mixed-Media on Wood | 8”x8”

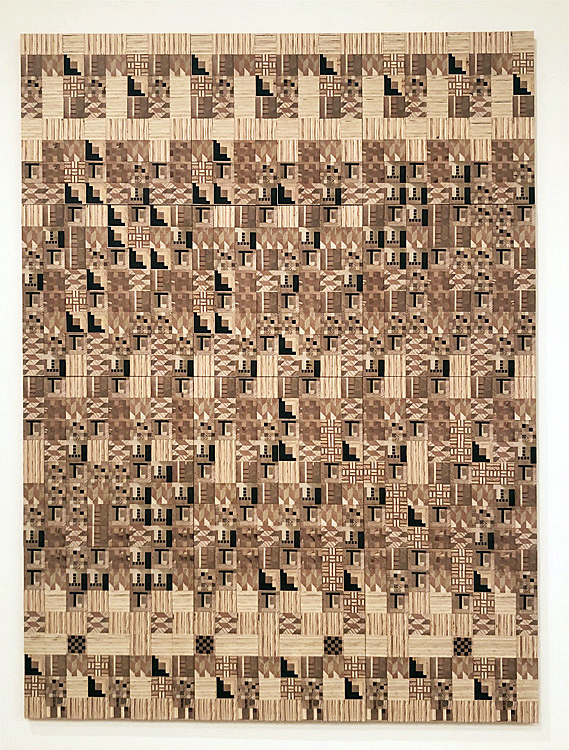

Olivia Guterson’s Sankofa, is reminiscent of Ghana’s Akan tribe and the mythical bird that serves as one of the Adinkra’s cultural symbols. With its head turned backward, the posturing speaks to embracing “what is at risk of being left behind.” Further, the three syllables that make up the word “Sankofa” mean return, go, look, seek and take. With this in mind, Guterson’s illustration welcomes a form of travel and seeking wisdom. There’s a present comforting that feels ancestral and communal. The artists’ use of black-and-white, textured lines and eyes throughout the image, brings both intensity and a sort of calm on this quest for knowledge and using the past as a guide to the future.

Olivia Guterson | Sankofa, 2020 Oil and ink on archival paper | 10×14

Throughout Jackson’s curation, we see the complexities and layers of the Black experience. We see love, the rich appreciation of literature, music, connection, progressive thinking and being amid the struggle and the striving. Souls of Black Folk: Bearing Our Truths is a looking glass for not only a deep dive into DuBois’ philosophy but that of Black life as narrated by Black visual artists.

View closely, Black voices have stories to tell. And this exhibition SPEAKS.

“The human soul cannot be permanently chained.” – W.E.B. Dubois

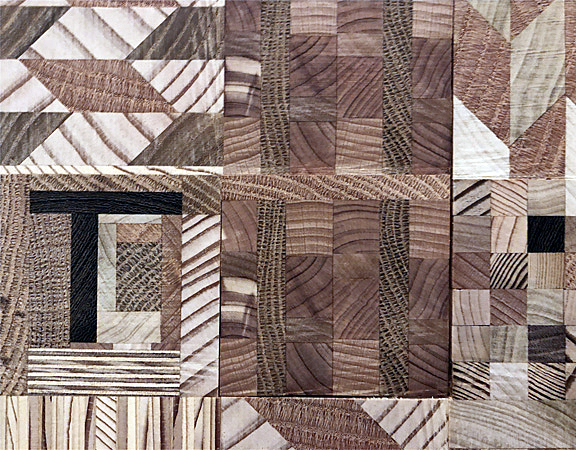

Desiree Kelly | W.E.B Du Bois | Woodburn, oil, acrylic, collage on wood | 12 x 12

Participating Artists: Monica Brown, Taurus Burns, Cydney Camp, Rita Dickerson, Olivia Guterson, Asia Hamilton, Donna Jackson, Sydney James, Ralph Jones, Desiree Kelly, Charles Miller, Carole Morisseau, Sabrina Nelson, Yvette Rock, Phillip Simpson, Mandisa Smith, Rachel E. Thomas, Charlene Uresy, Carl Wilson, Cara Marie Young

Souls of Black Folk: Bearing Our Truths – On Display at the Scarab Club until March 20, 2021

ALSO ONLINE: https://www.soulsofblackfolk.com/