The Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center has three new exhibitions that are complementary

Iris Eichenberg, Alberte Tranberg, Shelly McMahon, Emergence Property, Installation courtesy of DAR

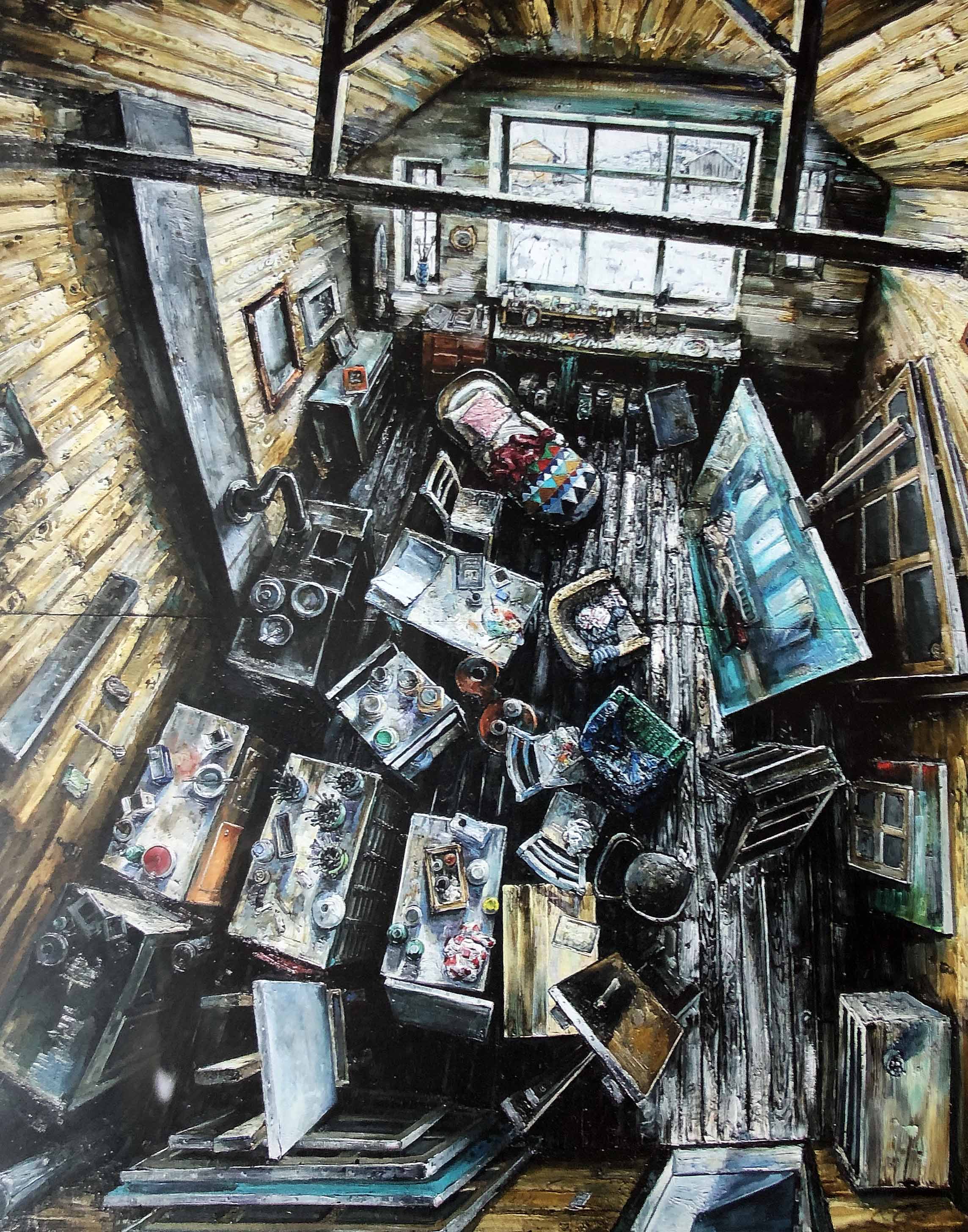

Having just returned from New York City and viewed the OPEN CALL exhibition at the new museum in Hudson Yards, The Shed, where it afforded me the opportunity to experience 22 art installations that were juried and funded for a group of New York Artists. Now back in Detroit, it has given me some context to view and experience the new art installation at the BBAC, Emergence Property, largely conceived by the artist Iris Eichenberg. This nearly all steel structure takes up the entire floor space in the Robinson Gallery, leaving only a 30″– 46″- 26″ path around the perimeter only to stop before it meets the first leg of the rectangle.

The installation is a collaboration of three artists, Iris Eichenberg, Shelly McMahon, and Alberte Tranberg whose work consumes the floor of the gallery, with one end of the space housing a pool of light, while the other end gradually ascends to a platform with delicate charcoal sculptures reaching upward, accompanied by a variety of flat rectangular screens of smoked glass varying in size. In addition, and not to be understated, the regular 2 x 4 ceiling tiles have been removed so as to reflect a grid that conforms to the layout of these steel weathered steel plates on the floor. There are several light bulbs hanging down from the ceiling in what appears to be random locations.

Iris Eichenberg, Alberte Tranberg, Shelly McMahon, Emergence Property, Installation image courtesy of DAR

This is not a group show, but a collaboration and they say in their statement that Emergence Property represents “the phenomena of collective behaviors by bodies larger than oneself. It is most commonly associated with flocks of birds whose movements in unison are executed unrehearsed and close proximity. Often these are evasive maneuvers which are transferred among the flock. This collective property begins with one, whose slight adjustment results in a rippling effect, shifting behavior on a large scale.”

I assume the artists refer to what is called murmuration, (large groups of birds flying in exact formation) and because that analogy was not clear to me, I asked Eichenberg to elaborate on the art installation.

Ron Scott What was your inspiration for the art installation and is it your first?

Iris Eichenberg It’s not my first. I would not call it inspiration but a shared interest in space , process and materiality to start with. We took on the grid of the ceiling as an external architectural and physical obstacle and rather than ignore it, we embraced it. We took the grid as a given as you can see on the floor. The patina of the floor might be a sky or the sea. As our conversation about emergence properties included the murmer of birds ….a simplification of what you see is the collapsing murmur of birds in the sky. But then again there is so much more going on which emerged through the interdependent process. I find space in limitations. That ceiling was restrictive, dominant and limiting. We turned the room upside down and then moved in.

RS Is this art installation a collaboration of ideas by three artists or were the other two artists on board for their expertise?

IE It is a collaboration of kindred minds who found their voice together. I cannot answer for them, but to me they were on board for the different sounds we make, for the mind which is not my own and foreign to me but getting sometimes closer to my intent than I might be able to by myself. The working process was one of trust and ego management. An ongoing unfolding of adding, deleting and change of course. The work for sure is the result of a collaboration on various levels, taking each other’s material to a different place, opening space for each other but also ending each other’s sentences.

RS Could you explain the idea of limited space around the perimeter for the viewer to walk or stand?

IE Exclusion is an effective tool to raise attention to those who assume to be included. The space is dark yet beautiful. The push and pull of seduction and exclusion complicates the relationship. Being pushed to the margins of the work, reduced to voyeurism, the viewer is not part of but outside and alone. That loneliness of the observer plays into the worldview of the piece. The awkwardness made people stay rather than leave.

RS In your statement, you refer to the phenomena of collective behaviors by bodies larger than oneself, so how does that relate to these metal plates and structures on the floor?

IE The work or the material is not an illustration of that thought but the process of picking up on one’s energy, enabling each other. Appropriating the potential of the other allowed for decisions none of us would have made. That is the phenomena we are talking about in the text. The metal plates are the vernacular of one of us. What they become in combination with the other elements is a dynamic energy and ultimately a force beyond the individual participation.

RS What was your thinking about the need to remove ceiling tiles?

IE We did not remove them. We found the voided ceiling, the void is what we embraced in shape, material and matter. It was the restriction we took on the unavoidable we accepted as a basic condition and, rather than ignoring it, we allowed it to define the mirrored ground space. In more than the grid we reversed ceiling and floor. The mirrors even fuse/confuse the identical grid.

Iris Eichenberg, Alberte Tranberg, Shelly McMahon, Emergence Property, Installation detail. Image courtesy of BBAC

I did learn more about this installation of art from this interview with Eichenberg and, as a result, I perceive it more deeply. Let’s step back and realize that art installation is a relatively new genre of contemporary art and is temporary by nature. The ideas presented tend to be more important than the quality of its medium and largely are site specific, designed to transform the perception of space. By using the metaphor of a murmur of birds, I was not sure she was referring to the art or the relationship of the artists. Perhaps both. It has not been my own personal experience to be limited, even one might say captive, while viewing art, so with regard to the small and restrictive pathway around the work, this juror is still out.

When I think back to Étant donnés by Marcel Duchamp, or I Like America and America Likes Me by Joseph Beuys, I can easily support the concept of art installation as an important genre, and in the case of Emergence Property, it will likely transform the Metro Detroit area by surprising audiences and engaging viewers in new ways.

Iris Eichenberg earned her university credentials from Gerrit Rietveld Academy, Amsterdam, NL and is the recipient of numerous awards and grants. Alberte Tranbert earned his MFA from Cranbrook Academy in 2018, and Shelly McMahon earned her BFA from the University of Oregon, and her MFA from Cranbrook Academy in 2018.

Gregory Thielker: The Wall

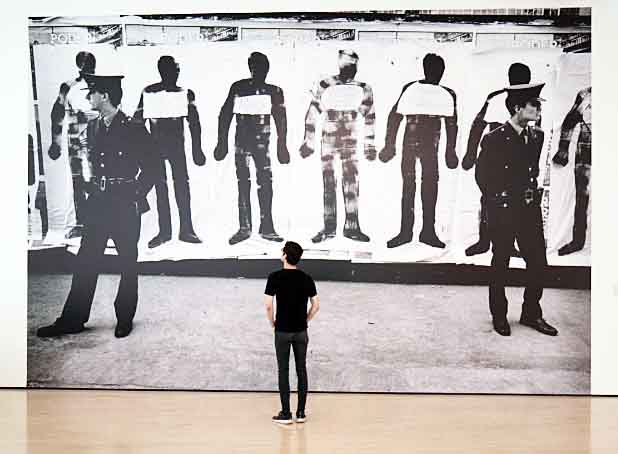

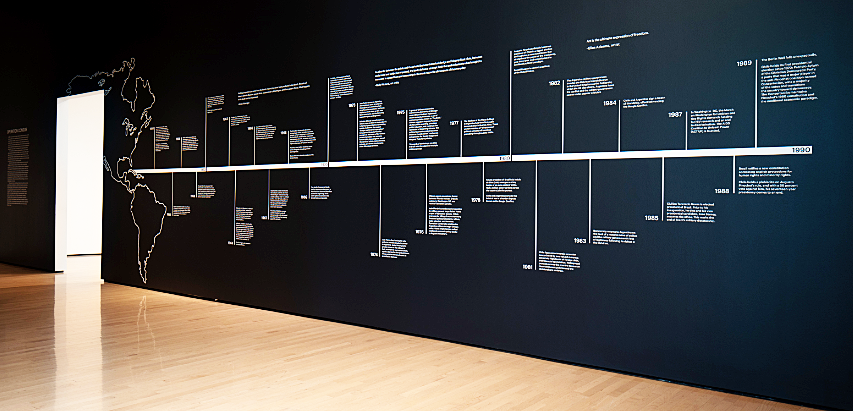

Gregory Thielker, installation, color photographs & objects

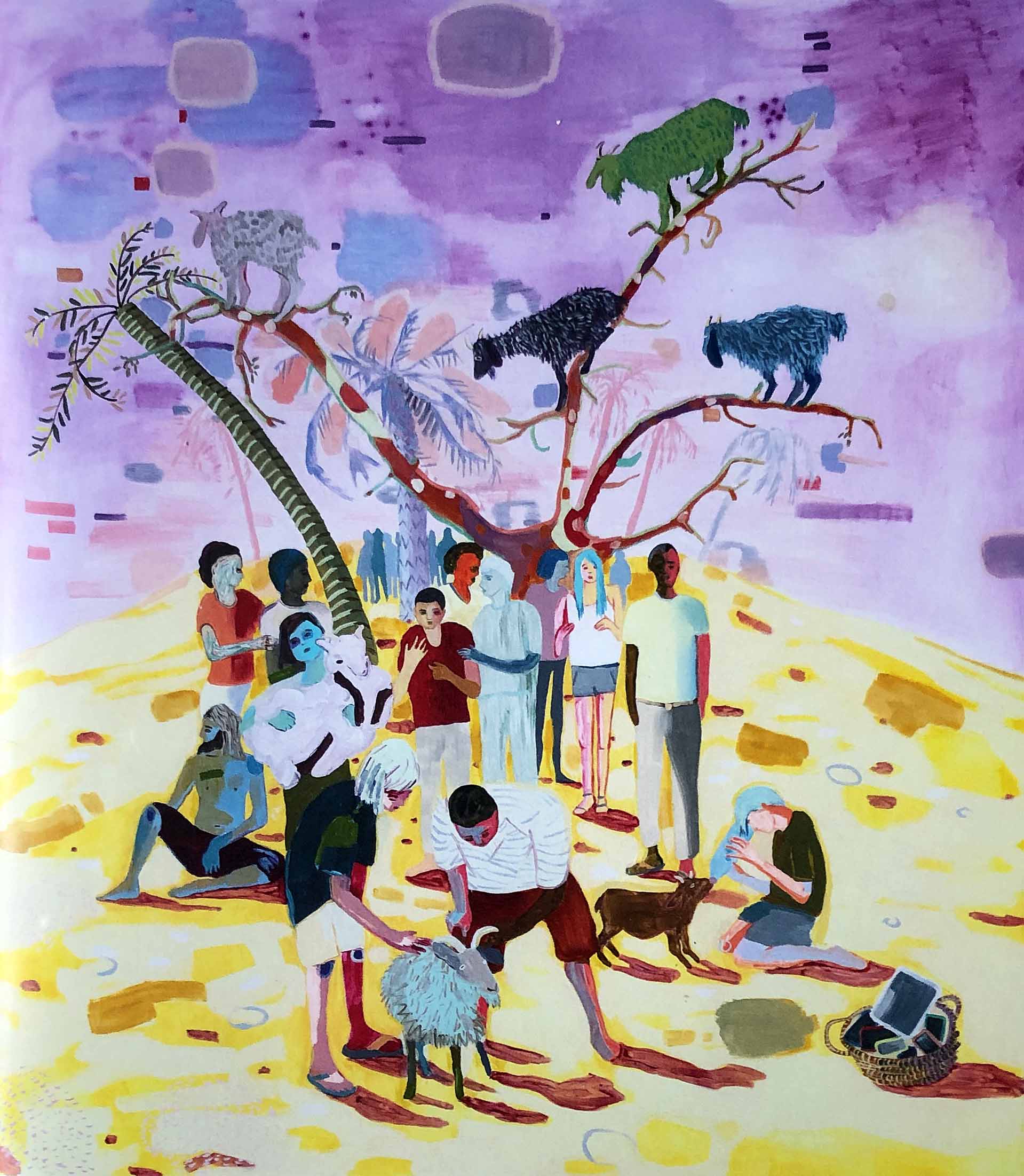

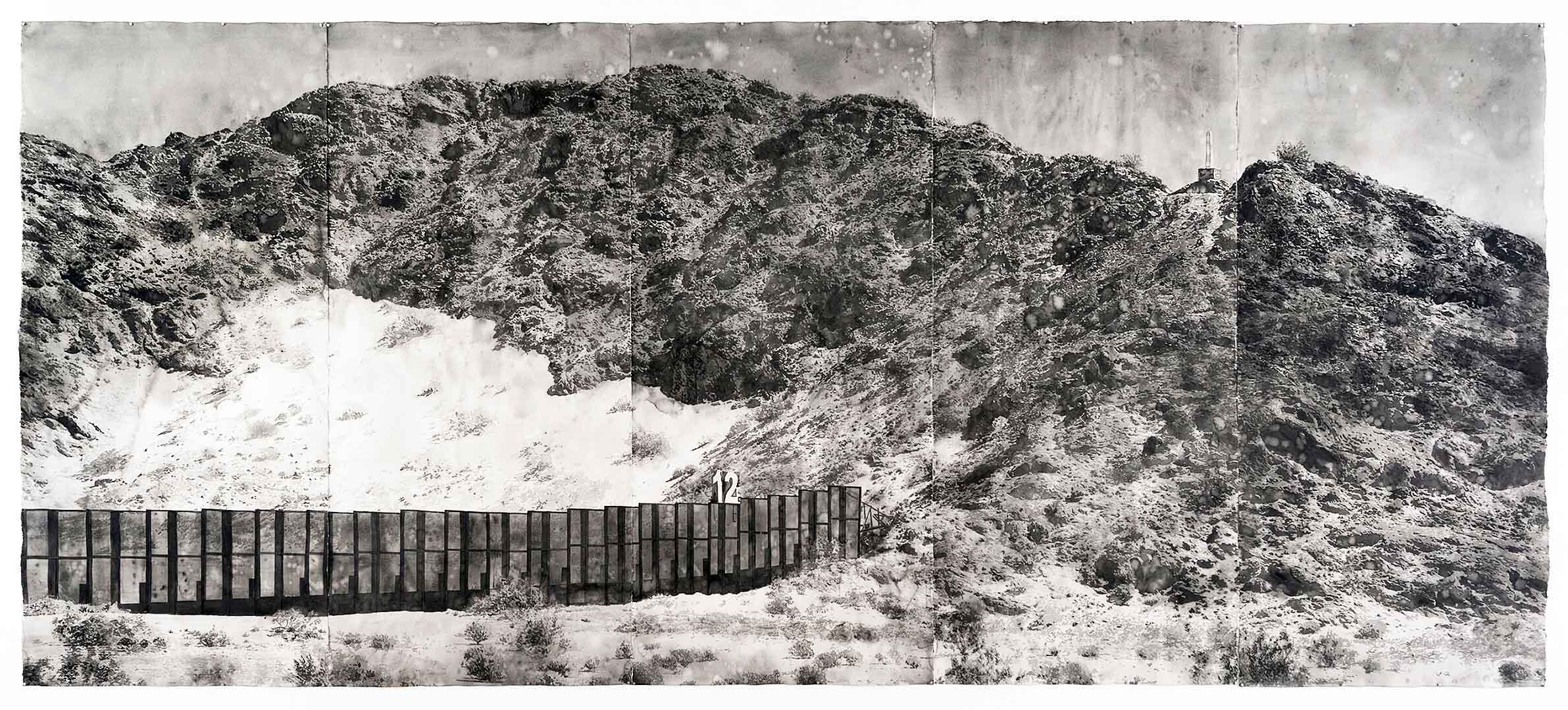

It should not surprise anyone that artists are drawn to issues of social justice. Just look at the headlines from the Whitney Biennial 2019 culminating in the forced resignation of board member Warren B. Kanders, or the uproar over Purdue Pharma and the Sackler family. In the current center gallery at the BBAC is a visual portrait of the border territory between the U.S. and Mexico where the visual artist Gregory Thielker has an exhibition of both black & white, and color watercolors (and color photos) that depict various views of the border wall, from tall steel barricades to sheet metal fences without containing humans, just the landscape.

He says in his statement, “This is a visual portrait of the border territory between the U.S. and Mexico. I traveled to different sections of the border region, crisscrossing back and forth, interviewing local community members and documenting the diverse terrain. The result is a series of black and white watercolor paintings ranging from small, intimate views to a large mural.”

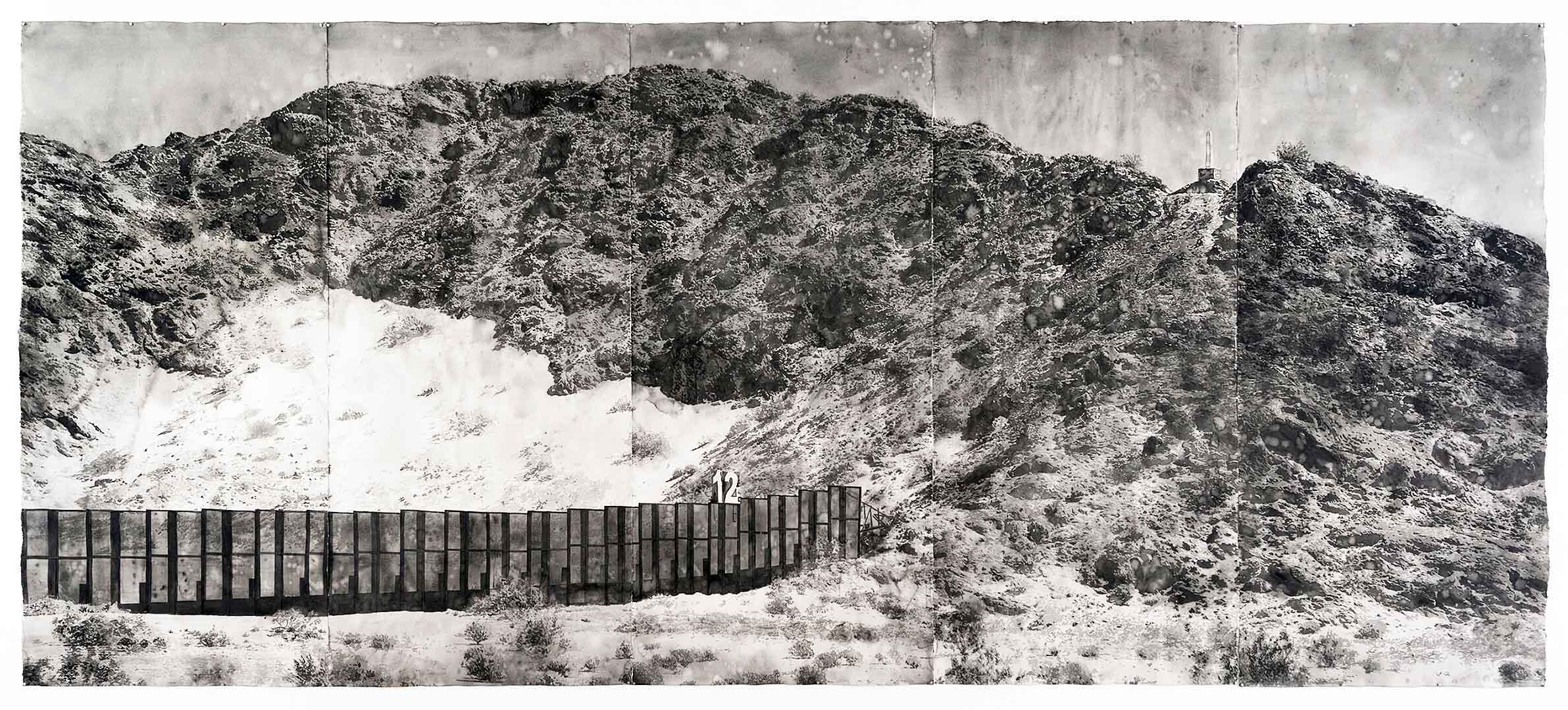

Gregory Thielker, The Wall, watercolor on paper, 96 x 225″

At first glance, you might think you are experiencing photo images, but on closer examination, some of these photo-based paintings are watercolors. Just the scale of this painting is impressive, divided into five sections and measuring 96 x 225”, the photo realistic watercolor dominates the gallery space. There is a feeling of border patrol presence, just from the number 12 and the structure in the upper right-hand corner. This exhibition evokes the headlines in our daily news where images of people from the southern part of North America are fleeing violence and oppression to seek asylum in the United States. The collective of these paintings rings in our heads the sonnet by Emma Lazarus, “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

Gregory Thielker earned his BFA from Williams College, and his MFA from Washington University in St. Louis Missouri, in painting.

Animal Pleasures – Small Etchings by Alan Larkin

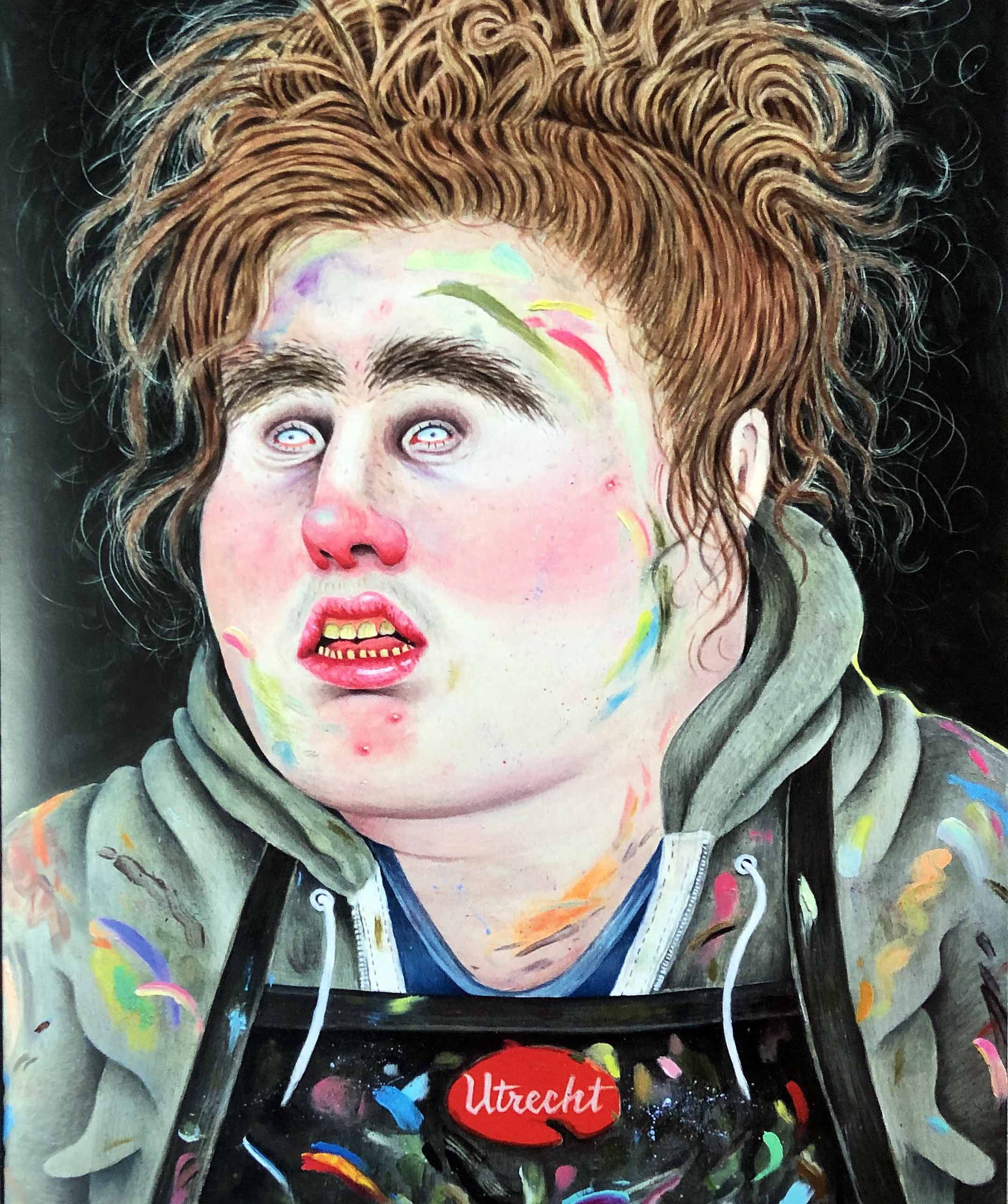

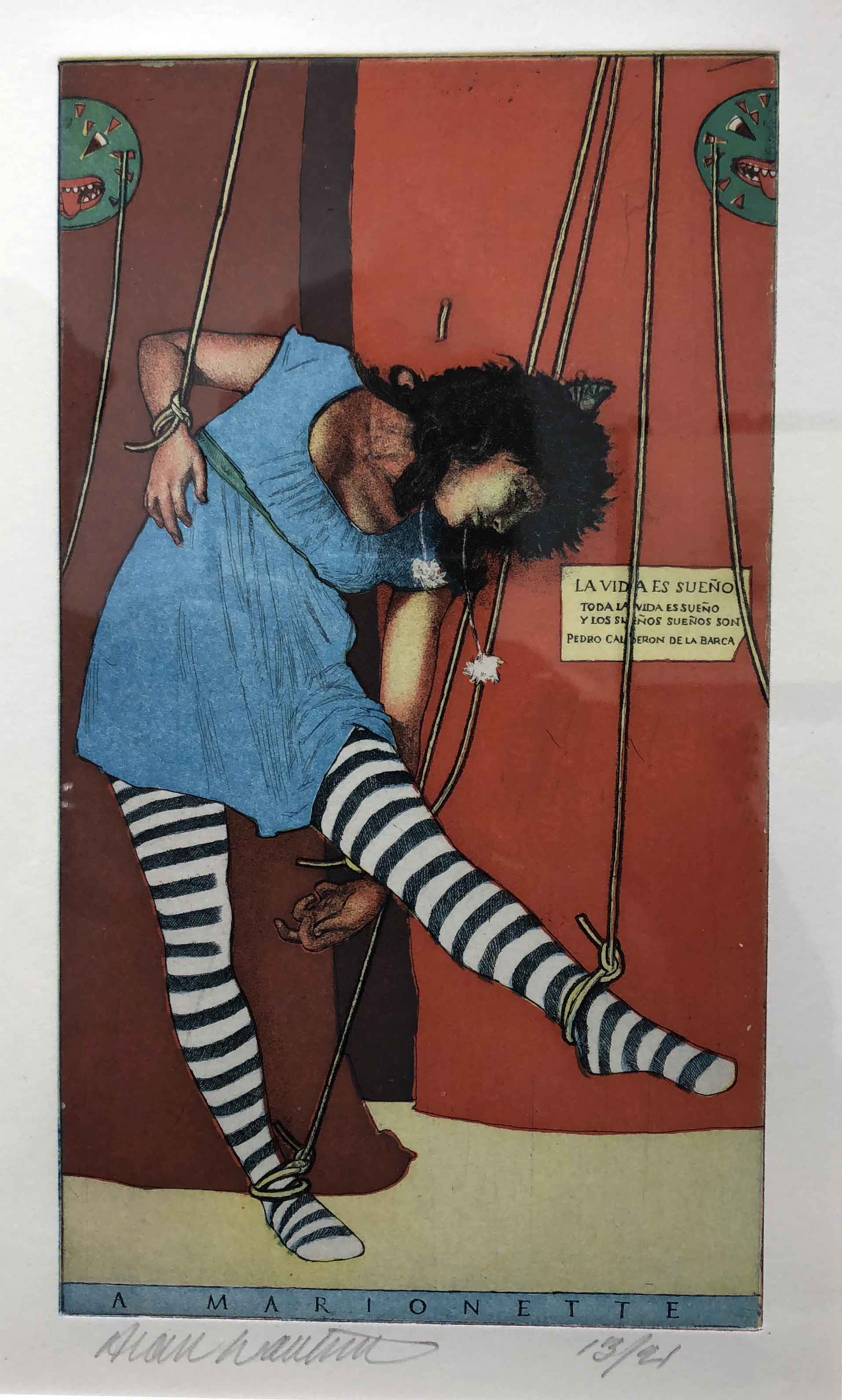

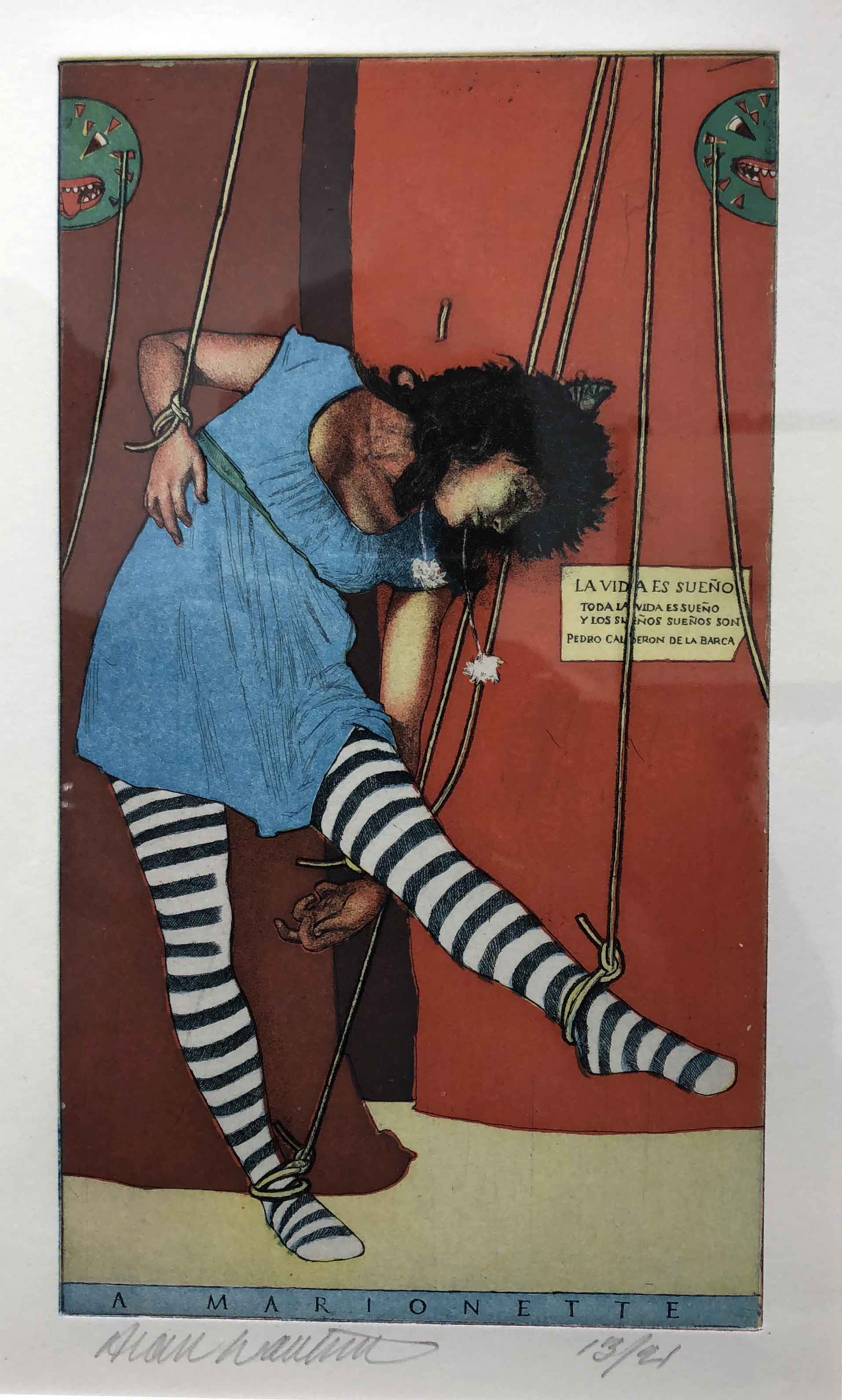

Alan Larkin, A Marionette, Etching & Aquatint

I have seen Alan Larkin’s work in the BBAC Fine Art Competition exhibition and was delighted to see more of his printmaking in his small, intimate show in the Ramp Gallery. These etchings bring to mind a neoclassical feel, both in subject and execution. Larkin, an associate professor at Indiana University for thirty years, taught drawing and printmaking. In this Etching and Aquatint, “The Marionette,” Larkin provides the viewer with a lush and coherent three dimensional image grounded in composition , subtle primary colors and engaging design elements.

Larkin says in his statement, “Art should engage people’s interest both immediately and over time. When we stand in front of something it is often because it calls to us from across the room, but when we return to it we should discover something new. Objects that can have this power are not accidents. They are made by thinking people who learn how to connect their intellect with their emotions.”

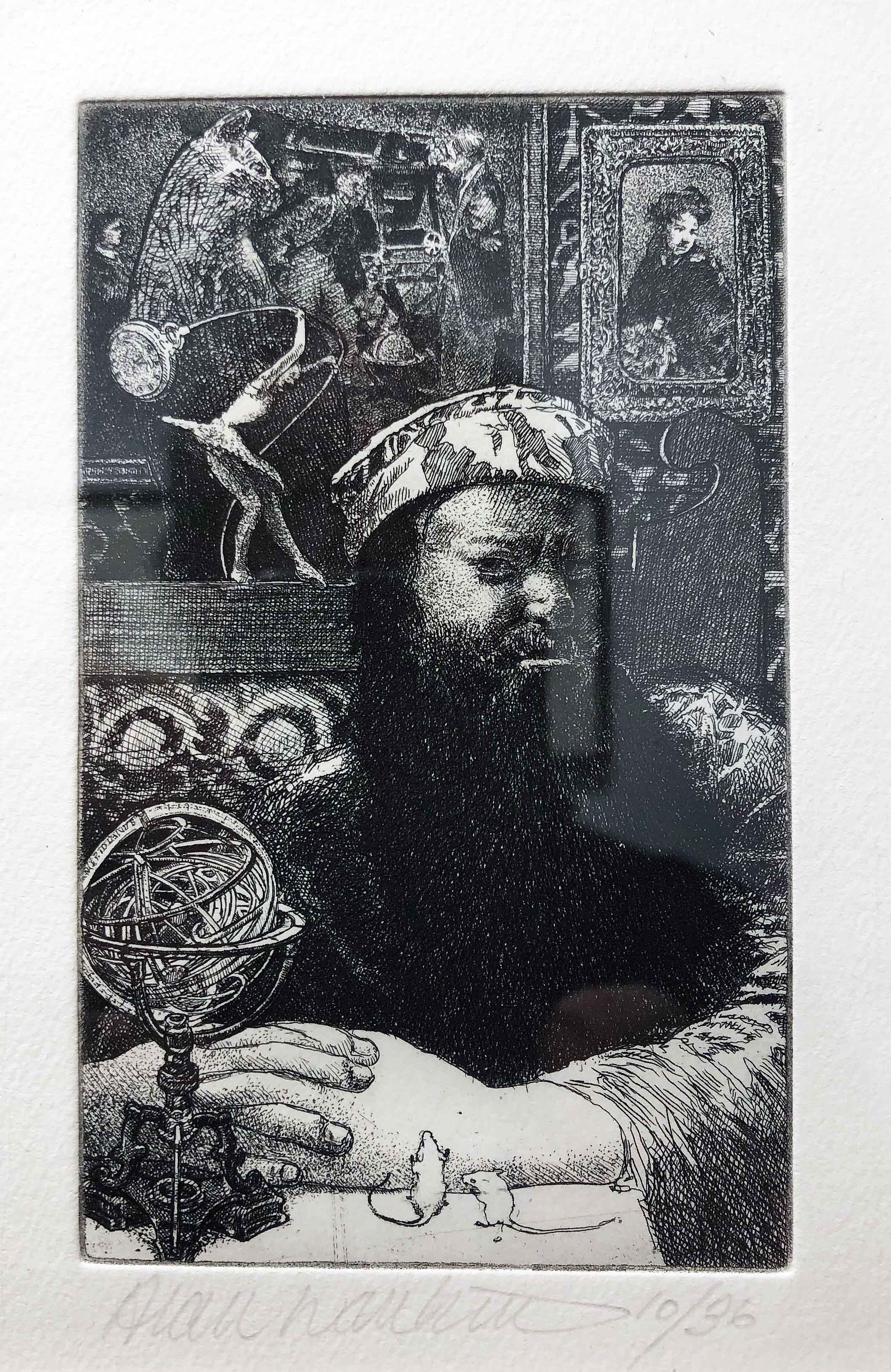

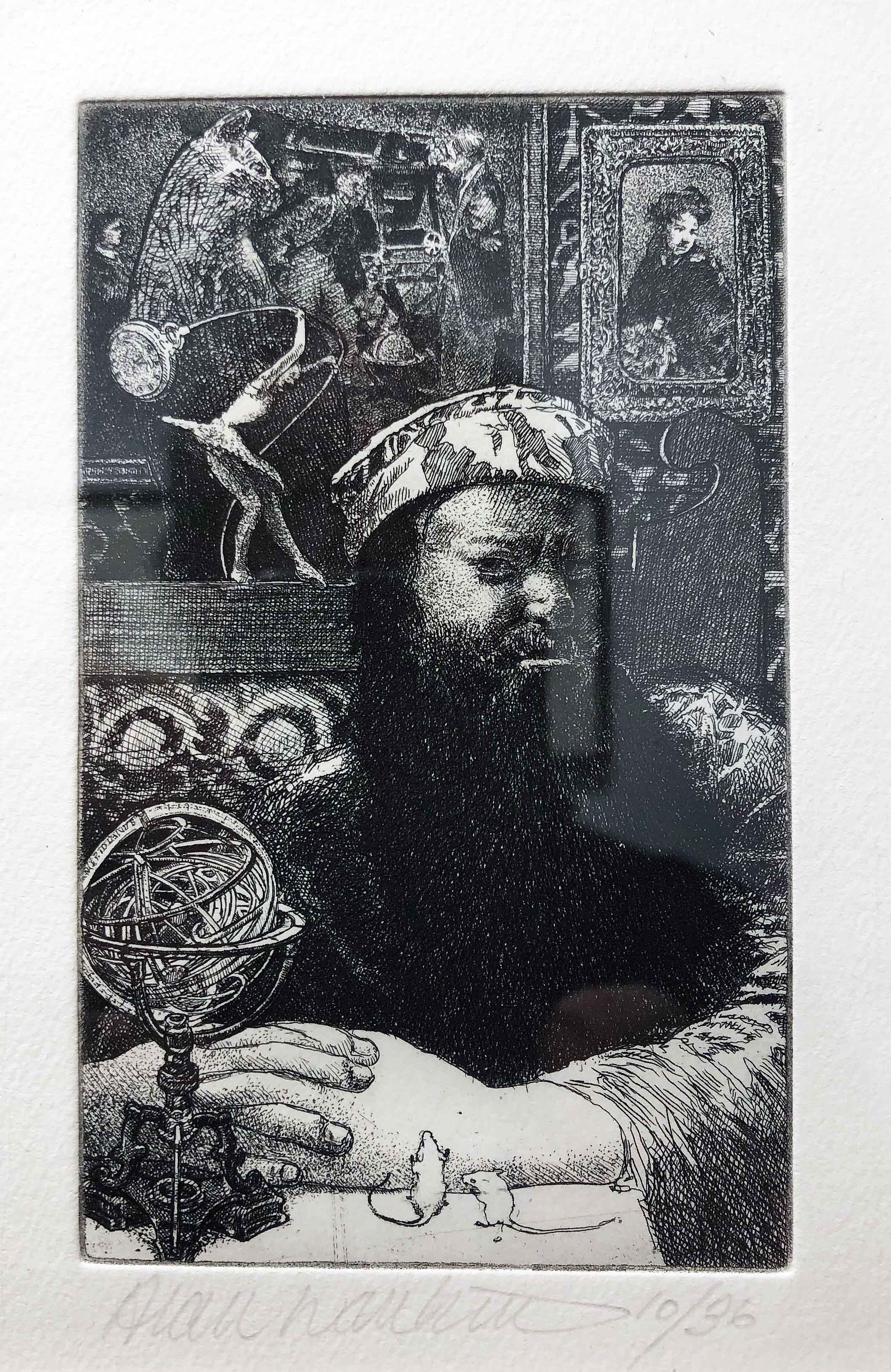

Alan Larkin, Oberon, Etching

The etchings are small and are executed with 000 needles, often under a microscope, drawn on copper plates and submerged in a Ferric Chloride bath and often go through multiple baths. I submit there is room for this oeuvre in our collecting, much like classical music, literature and photography. “It can be discussed and understood in a number of different ways: as a design in terms of its color, balance and movement, as a craft, in terms of its mastery, or even as a story, in terms of its emotional impact or its capacity to give us insight.” Larkin earned his BA in art from Carleton College in Northfield Minnesota in 1975 and his MFA in printmaking from Pennsylvania State University in 1977.

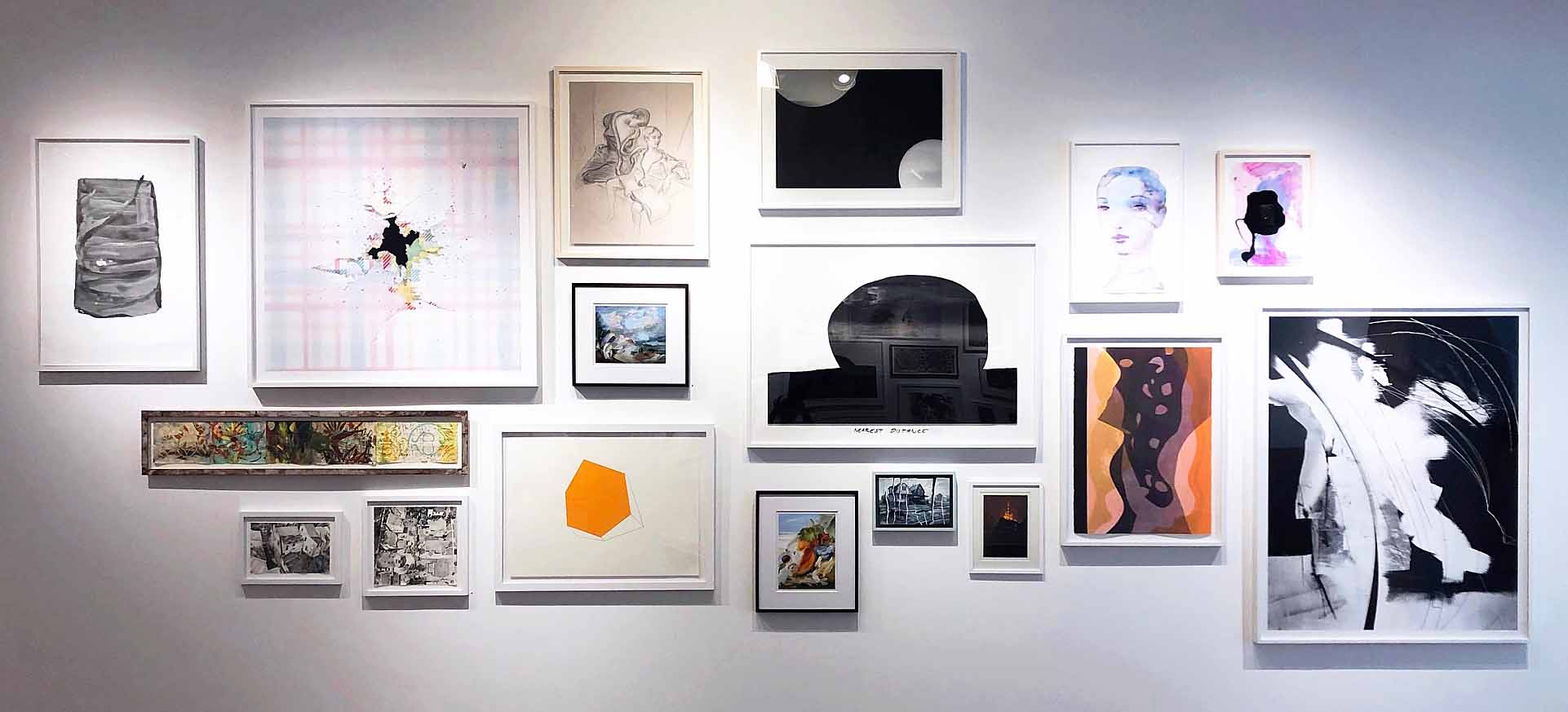

This collection of three exhibitions are complementary and demonstrate how the curation at the BBAC is not about sales, but more about providing the public with thought-provoking aesthetic experiences.

Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center – The Four Exhibitions will run through October, 10, 2019.