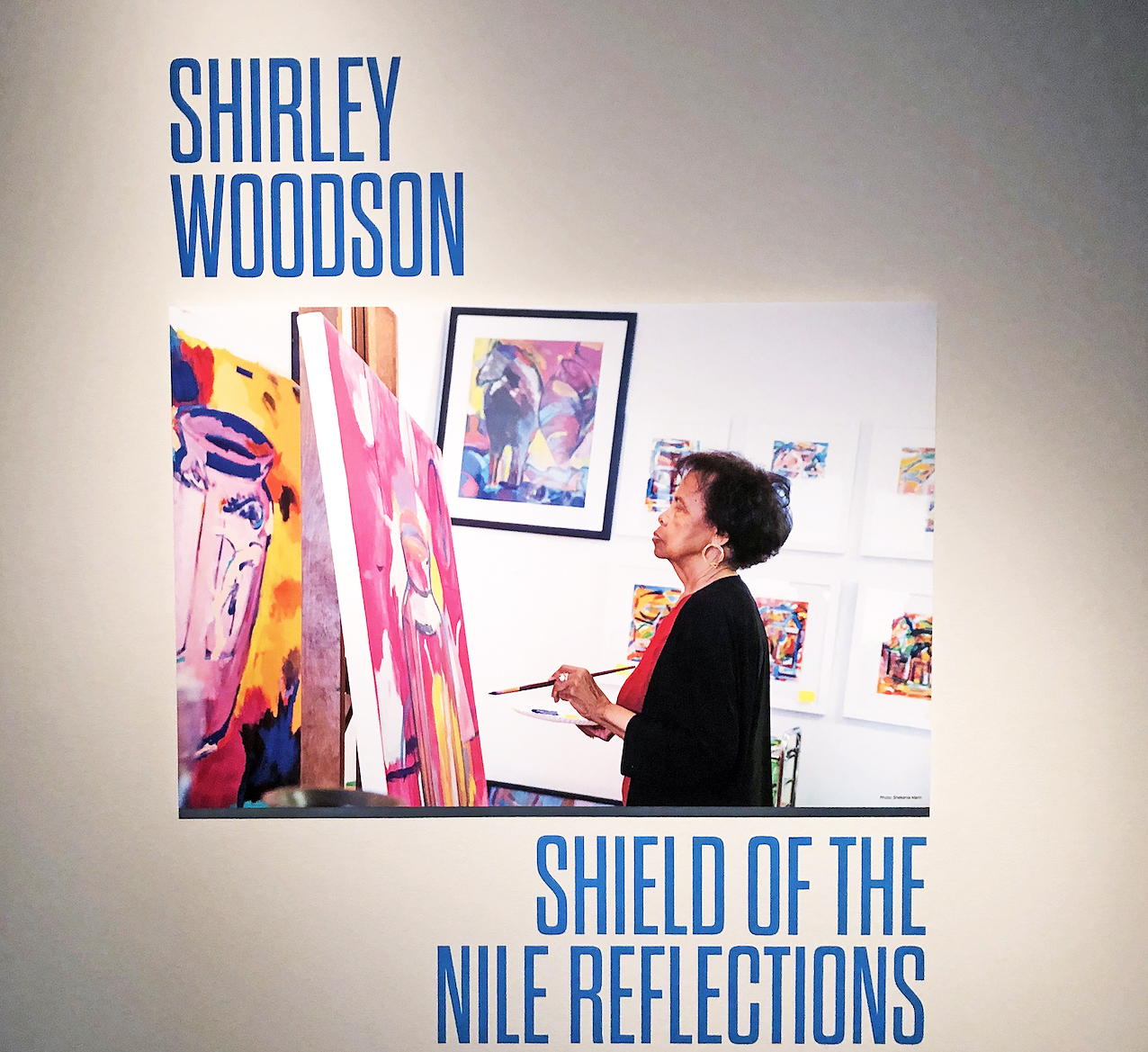

Oakland University Art Gallery presents: Image and the Photographic Allusion

Installation image OUAG: Image and the Photographic Allusion, 2022

The Oakland University Art Gallery opened a photographic exhibition on January 13, 2022, that will run through April 3, 2022. The curator of this exhibition is Dick Goody, Professor of Art in Oakland University’s Department of Art and Art History. Goody also serves as director of the Oakland University Art Gallery.

In a statement, he says, “Photography is thriving, but in a different way than before. We used to preserve our treasured paper snapshots in photo albums, but today, smartphone images have become digital ephemera. Incalculable numbers of them are taken only to be forgotten. Photography exhibitions like this give us pause to reconsider the aesthetic grandeur of a printed-out, permanent, archivable image. In no way a conceptual concern, these rarified images are nothing if not transcendental.”

Louis-Jacques Mand’e. Boulevard du Temple, 1838, Daguerreotype, 5 x 6.5”

Photography, when its end result is called a photo, a picture, or a pic, gives meaning to an image, real or abstract. The types are amateur, commercial, journalistic, scientific, and artistic with too many to name. Today, it finds its application into every part of human life. It was invented in France in 1829 when an artist and a chemist named Louis Daguerre obtained a camera obscura for his work on theatrical scene painting. Daguerre was put into contact with Nicéphore Niépce, who had already managed to record an image from a camera obscura using the process he invented: the early photographic process employing an iodine-sensitized silvered plate and mercury vapor. Daguerre got stuck with the process in his name, Daguerreotypes – that gave the early photographers the ability to preserve an image and their collective history. From these early images using glass and paper, the process eventually found its way to film and now to digital cameras containing an array of electronic photodetectors, all with the same intent: capturing light and forming an image.

Pieter Hugo – After Siqueiros, Oaxaca de Juárez, 2018 archival pigment print, 47 x 63 inches

Pieter Hugo’s work is dominated by images of the human figure and their condition. His work is informed by a self-taught approach to photography after beginning his career by starting out working in the Film Industry. Born in Johannesburg, South Africa, Pieter started taking photographs at the age of twelve when his father bought him a camera. He gained an impressive reputation and an enviable following for his documentary photography and his striking fashion images. Choosing to focus on marginalized or unusual groups of people, Hugo has published many books and has been exhibited worldwide. The South African artist currently lives in Cape Town.

He says in a statement, “While working in Mexico I was particularly looking at muralist paintings. This image was constructed using a group of garbage collectors who moonlight as a theatre troupe at the market where they work. I showed them a reference to a tableau from Alfredo Siqueiros and asked them to recreate it. I love the junction between premeditation and accident.”

Markus Brunetti – Wells, Cathedral Church of St. Andrews, 2015–16 archival pigment print, 59 x 70.8125 inches

Markus Brunetti’s work, Wells- Cathedral Church of St. Andrews, is part of a series titled Façades, which features a technically precise image of European religious buildings’ exteriors, primarily from the 14th century. This work reminds this writer of a time when cameras were fitted with architectural lenses that were adjusted when getting a perfectly flat image of a building. Using today’s technology, Brunetti depicts the facades of the building in a highly exact hyper-realistic manner by combining scores of individual frames into a single image.

He says in a statement, “The builders and architects that built the churches had to be patient. Most of them never saw the finished result of their endeavors, as it would take decades or sometimes hundreds of years to complete the building. I try to work on this series with the same spirit and patience they must have had when starting to work on those new historical monuments.”

Raïssa Venables – Sukkah, 2020 archival pigment print, 54 x 44 inches

The Sukkah image by Raissa Venables is a large-scale photograph that requires numerous photographs stitched together to form the illusion of movement without a human presence. The illusion of movement is created from the use of multiple vanishing points. Assumptions of reality are disrupted, creating a realm where inanimate objects seem alive. The result is both an architectural puzzle and a landscape of the mind. It is a kind of interior environment that makes the viewer ask questions.

In her statement, she says, “At first glance, they may seem to be realistic images or even entrances into existing places. My photographs are experiential visions of our environments, whether they are interior or exterior, mundane or opulent. Rather than reveal visible details captured by my camera, I delete what I perceive to be distractions.”

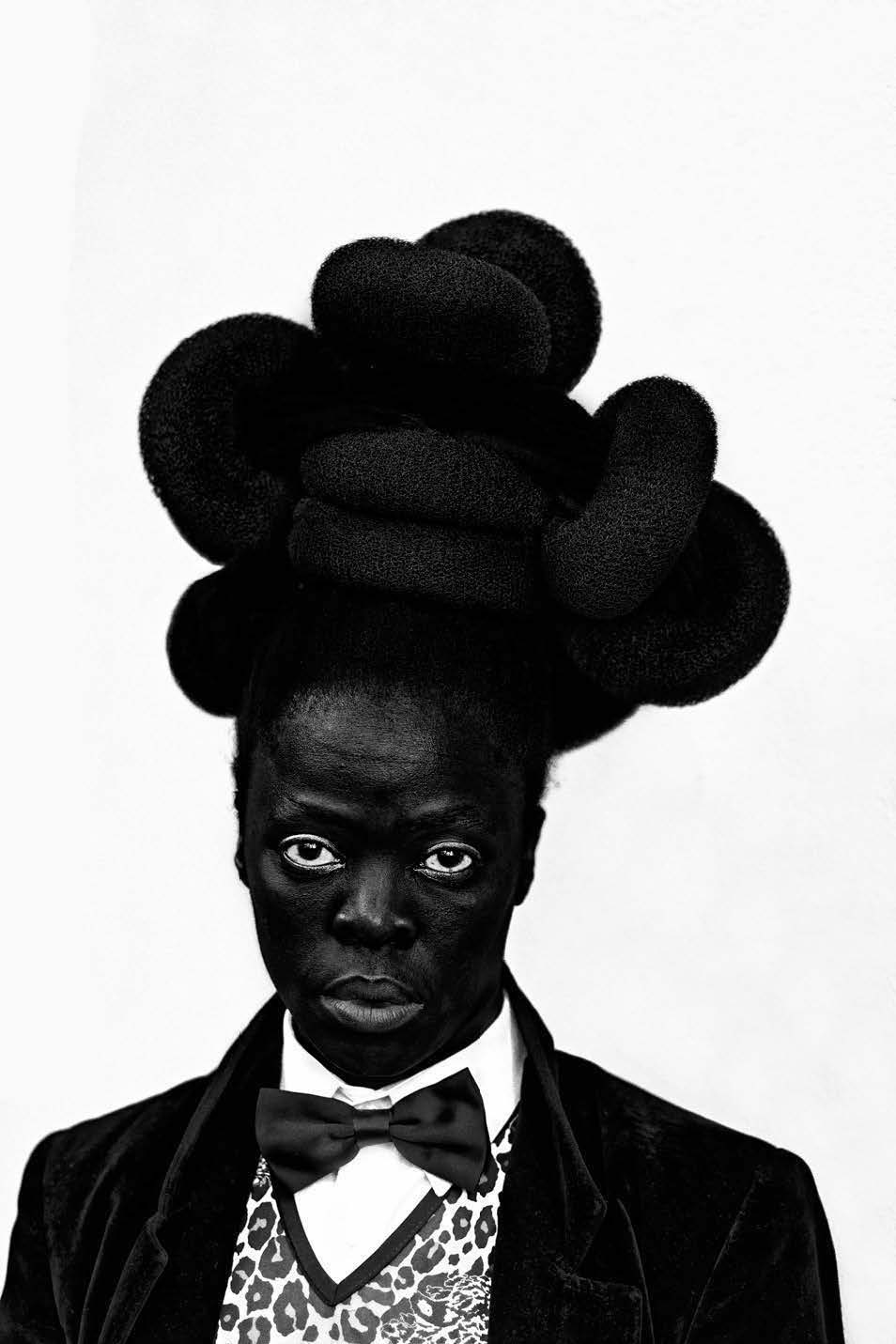

Zanele Muholi – Phaphama, at Cassilhaus, North Carolina, 2016 archival pigment print, 43.375 x 30 inches

Zanele Muholi is a South African woman who uses photography to capture portraits of black, lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, intersex people, including herself. Her images capture the realities of people she believes need to be heard. Her works in this exhibition are portraits of herself, where she intentionally darkens the exposure of her skin and compliments this with either her hair or the clothing she wears.

She says, “I wanted to use my own face so that people will always remember just how important our black faces are when confronted by them- for this black face to be recognized as belonging to a sensible, thinking being in their own right. The key question that I take to bed with me is: what is my responsibility as a living being – as a South African citizen reading continually about racism, xenophobia, and hate crimes in the mainstream media? This is what keeps me awake at night. You are worthy. You count. Nobody has the right to undermine you – because of your being, because of your race, because of your gender expression, because of your sexuality, because of all that you are.”

It is worth mentioning that many of these images are large prints (30 x 40-inch range), where scale plays a part in the art, and the printmaking is equal to the capture of the image. Most people don’t have or make prints, especially large prints, and when it is part of the creation it takes on an elevated meaning and presence. In addition, this exhibition is designed to give viewers an experience outside what is normally available to both students and the public alike and therefore differs in its audience and purpose. It is definitely worth a visit.

Artists represented: Mary Ellen Bartley, Peter Bialobrzeski, Markus Brunetti, Lucas Foglia, Cig Harvey, Jacqueline Hassink, Erik Madigan Heck, Pieter Hugo, Joshua Lutz, Michael Massaia, Jeffrey Milstein, Zanele Muholi, Christopher Payne, Toshio Shibata, and Raissa Venables.

The Oakland University Art Gallery presents Image And The Photographic Allusion, which runs through April 3, 2022