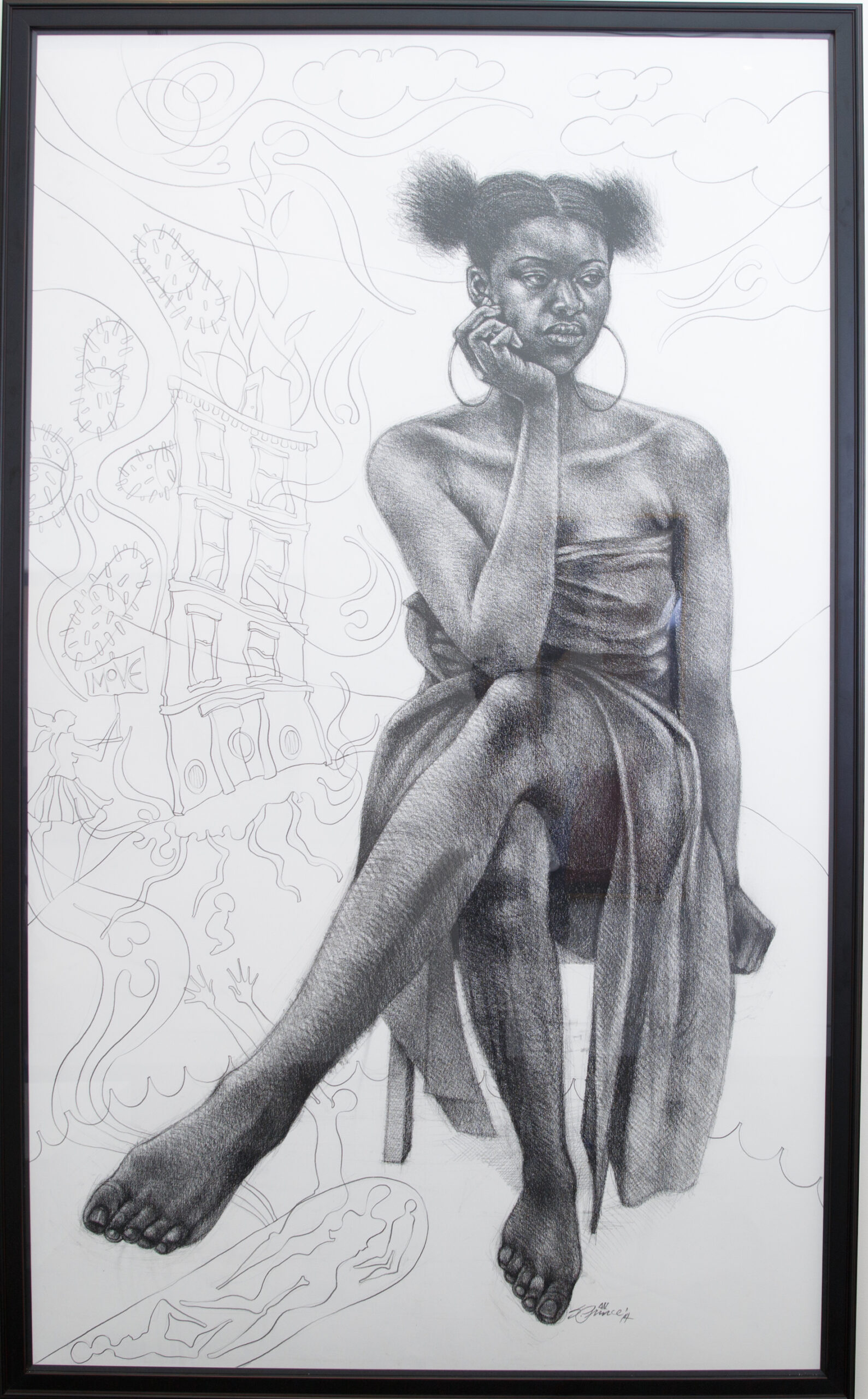

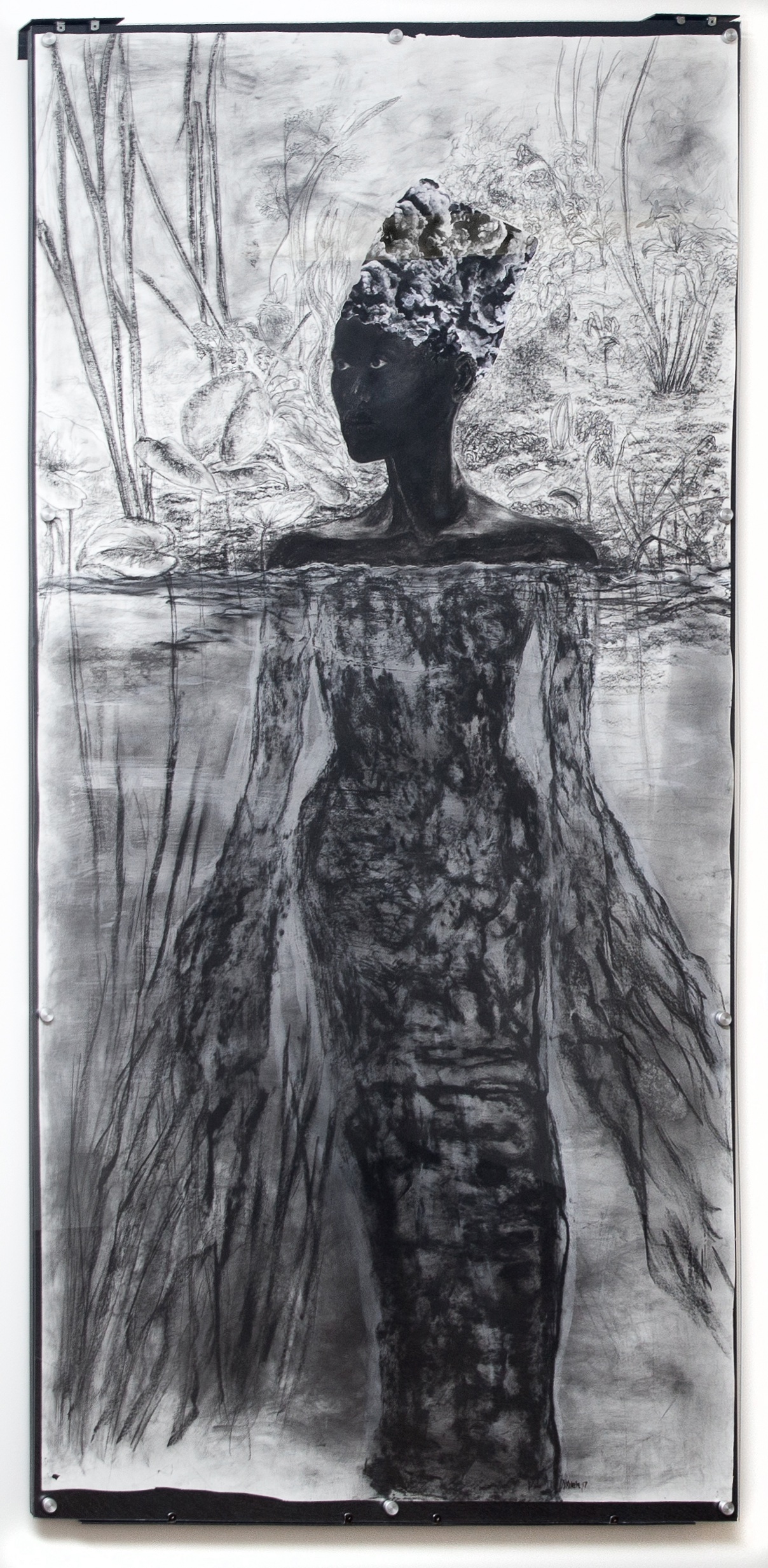

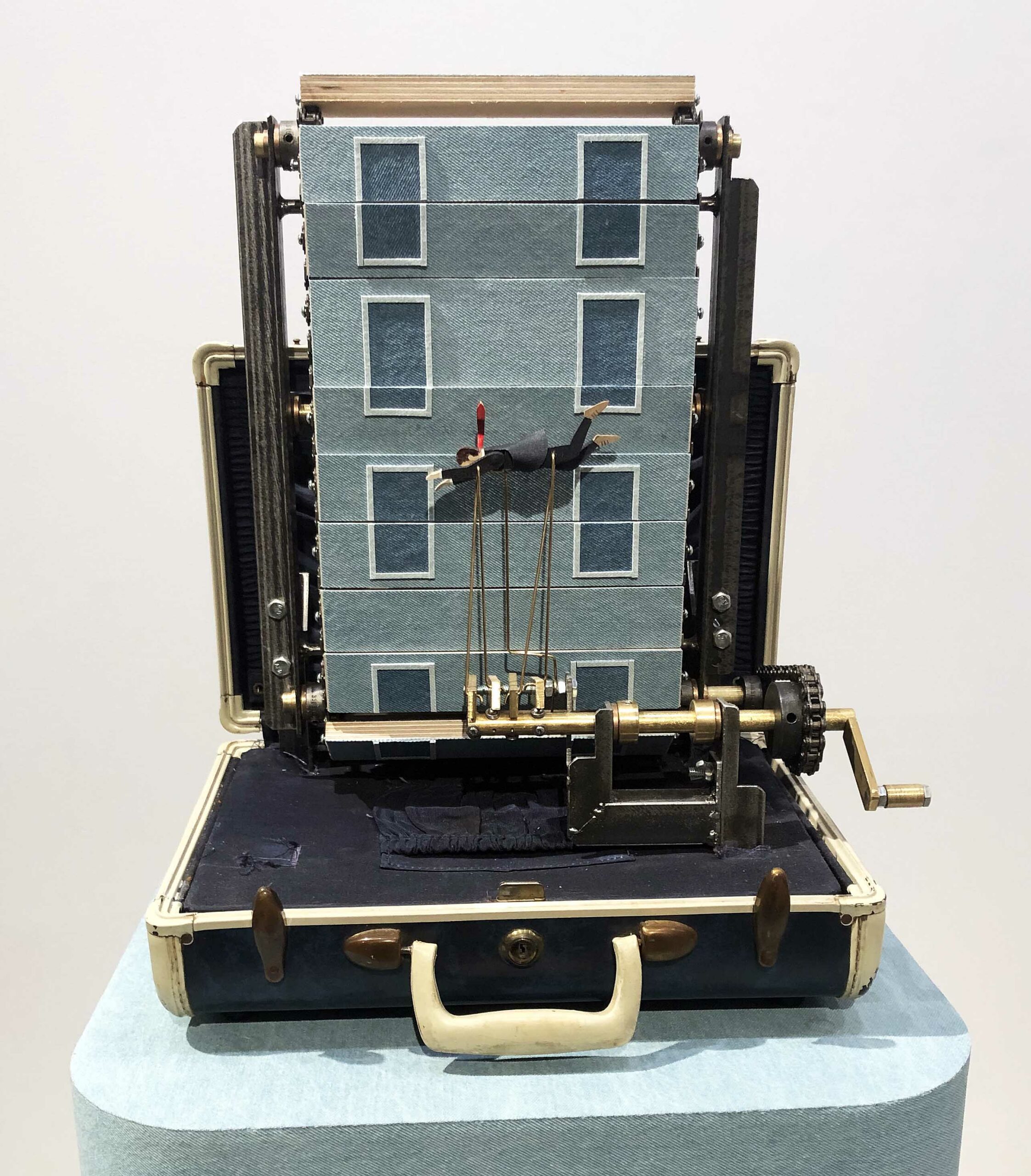

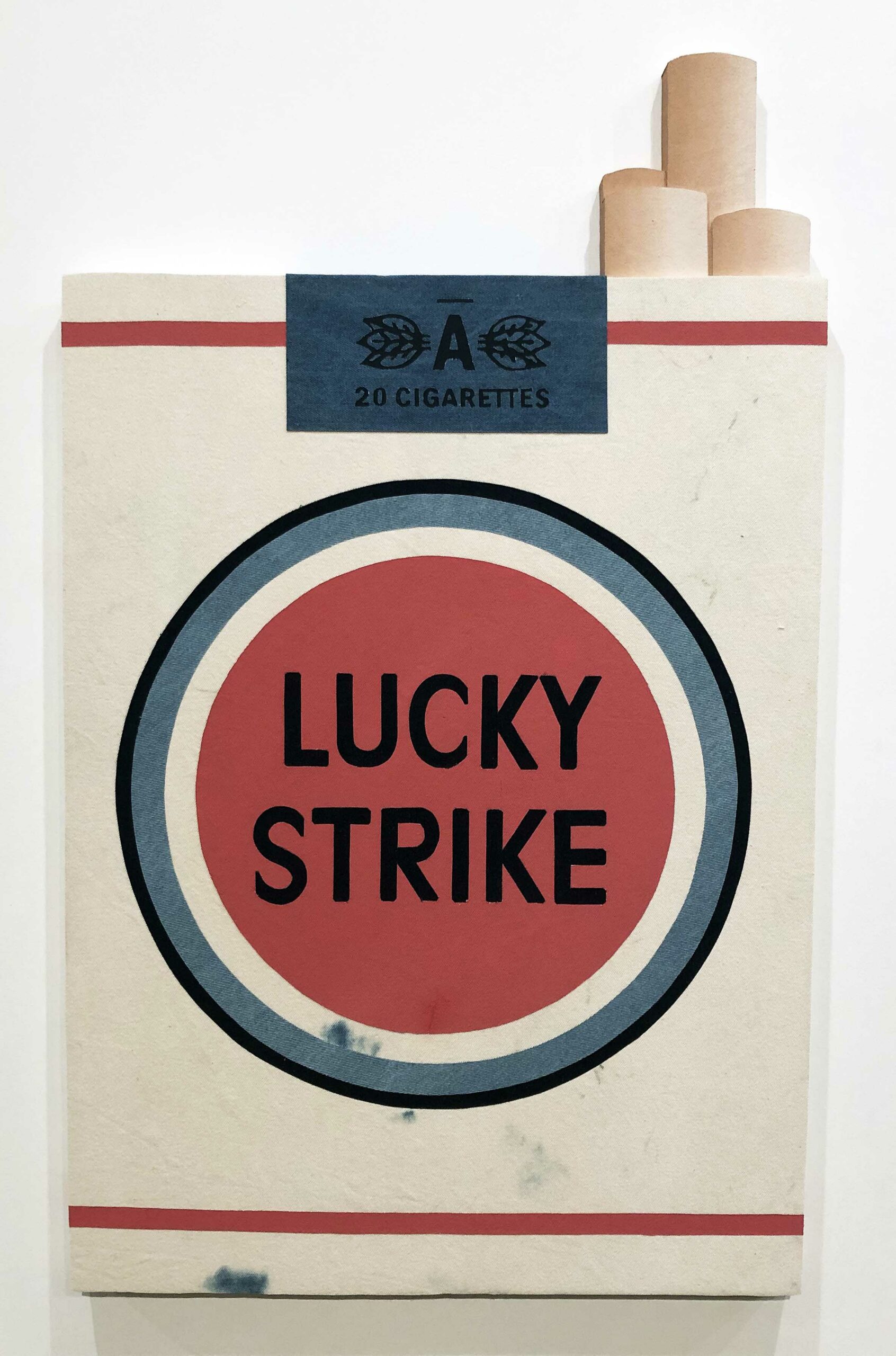

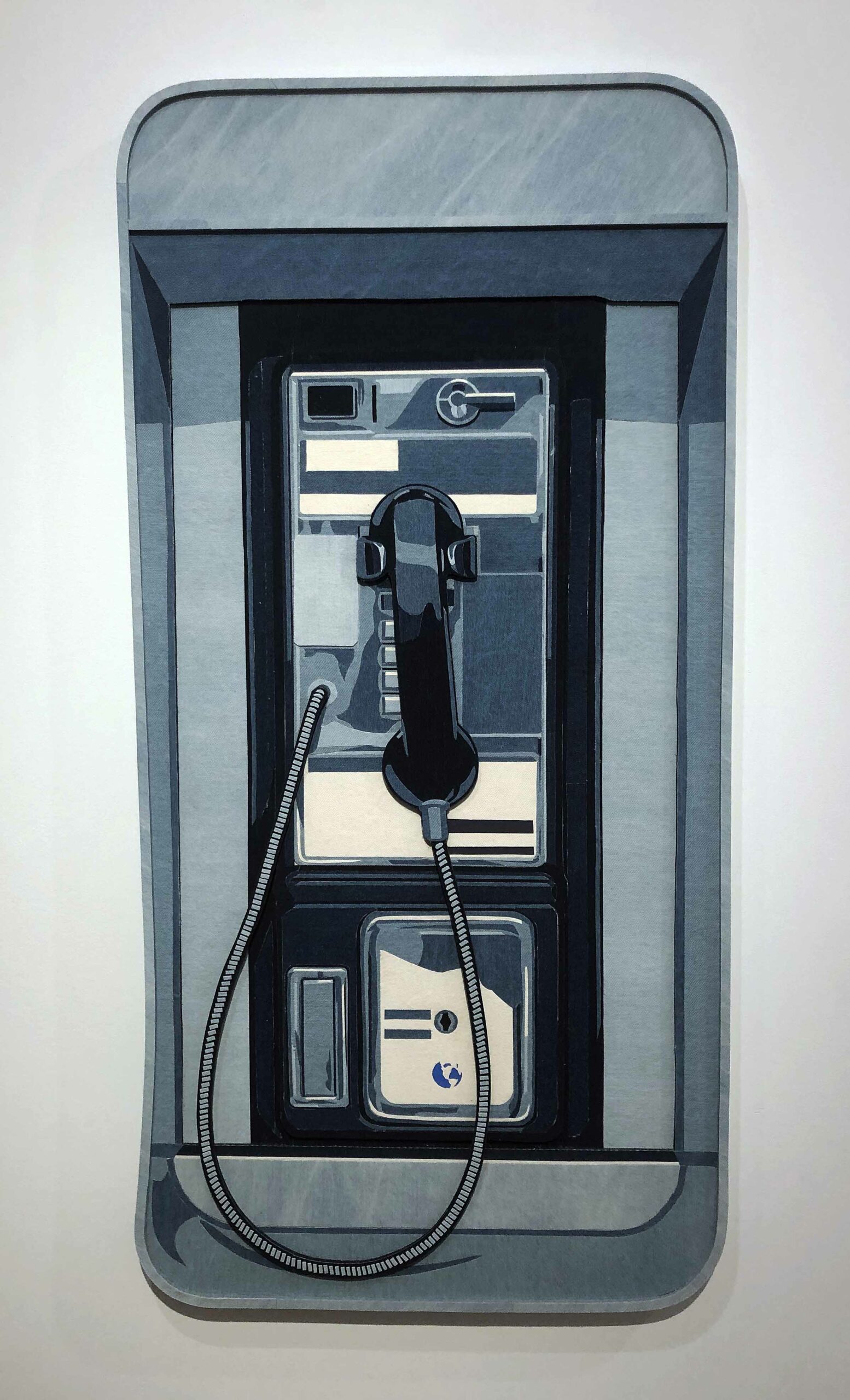

Installation View, All images courtesy of the Flint Art Institute

Two years ago, the Flint Art Institute opened the doors to its newly completed 11,000 square-foot Contemporary Glass Wing, supplemented by a 3,620 square foot glass arena where glassblowers offer demonstrations to audiences who can watch from stadium-style seating. Chic and emphatically modern, these new spaces seem to proclaim that while handcrafted glass is an ancient art, it’s also a medium for the 21st century and it will definitely be here in the future. The wing is home to a fine collection of eighty-eight glass artists representing sixteen countries, making this one of the best venues in the country for viewing contemporary glass.

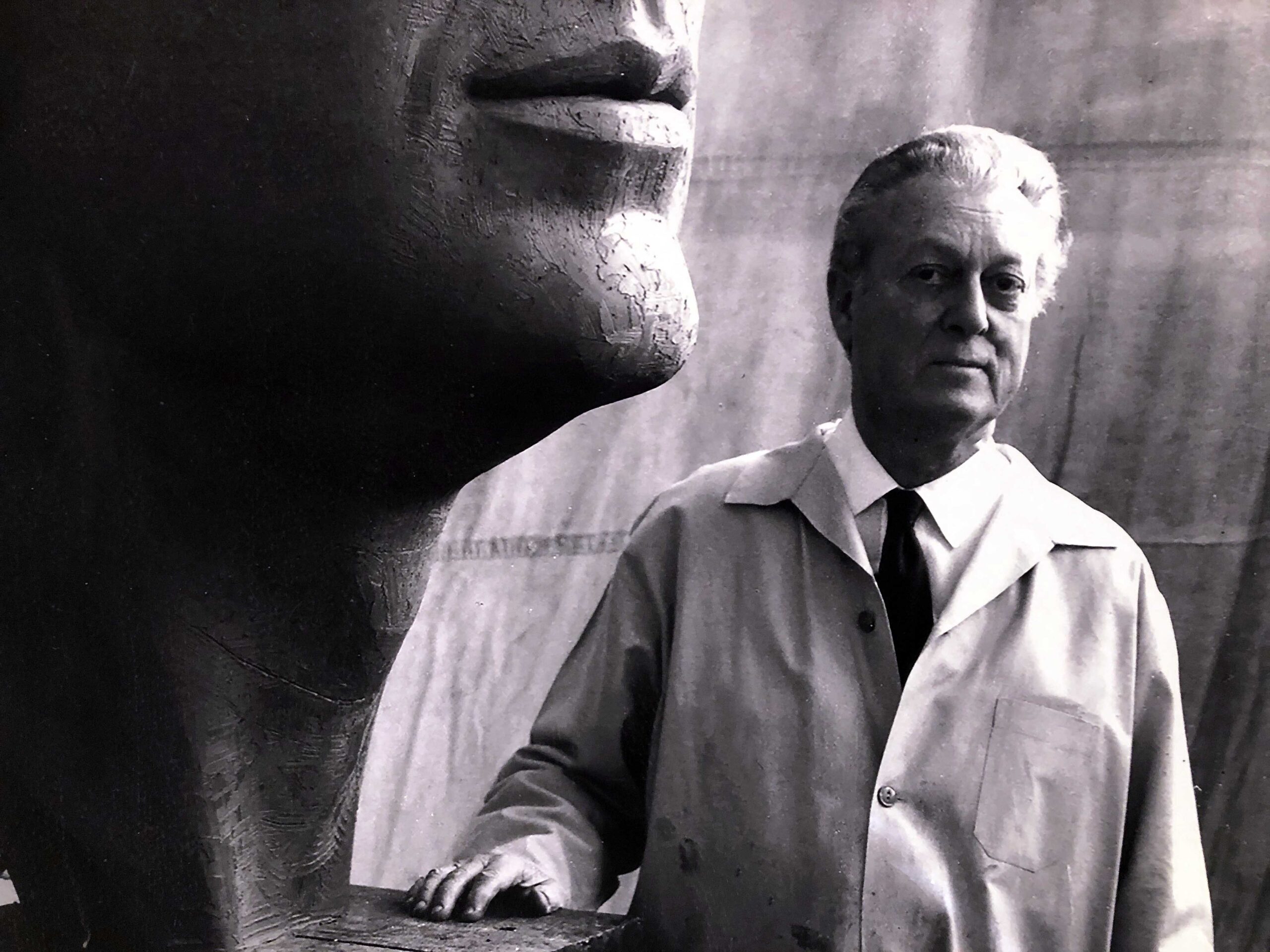

The works on view come from the collection of the serendipitously named Sherwin and Shirley Glass, and are currently on loan from the Isabel foundation. The heart of the collection is glass that emerged from the Studio Glass Movement, which had its roots in Toledo, Ohio–itself home to a fine glass collection. The movement began when Harvey Littleton and Dominick Labino engineered ways for artisans to create glass in their own studios with relatively small furnaces. They held a famous workshop on the subject at the Toledo Art Museum in 1962 (among others, Dale Chihuly was present), energizing the movement and creating the nexus which allowed for it to attain a global reach.

Suggesting highlights from the collection is a little difficult, given its strength. Karen LaMonte’s Dress Impression with a Traincertainly warrants mention. Here, viewers encounter a dress reminiscent of what you might expect to find draped on a Greek Aphrodite, except there’s no Aphrodite under these folds, merely a void created from a cast of a model. Her work subtly addresses the tension between the body and the spirit, though one’s principal thought will likely simply be “how did she make that?!”

Cast glass Dimensions: 58 5/16 × 22 1/2 × 43 5/16 in. Courtesy of the Isabel Foundation, L2017.143

Demonstrating the often-surprising trompe l’oeil possibilities of glass art, William Morris creates deceptive works inspired by African art like Zande Man and Bull Trophy, each seemingly fashioned out of wood and ivory. Similarly deceptive are the organic-looking elements of Debora Moore’s Orchid Tree, which looks uncannily like an arrangement of brittle fragments of twigs and withered petals. The overwhelming majority of works in this collection are sculptural, but Miriam Silvia Di Fiore’s Washing Boardapplies glass wire and thinly ground glass to create illustrative landscapes that seem almost painterly.

Blown glass, steel stand Dimensions: 26 × 16 × 16 in. (66 × 40.6 × 40.6 cm) Courtesy of the Isabel Foundation, 2017

Flameworked and kiln-worked glass, found object Dimensions: 30 3/4 × 16 × 5 3/4 in. (78.1 × 40.6 × 14.6 cm) Courtesy of the Isabel Foundation, 2017

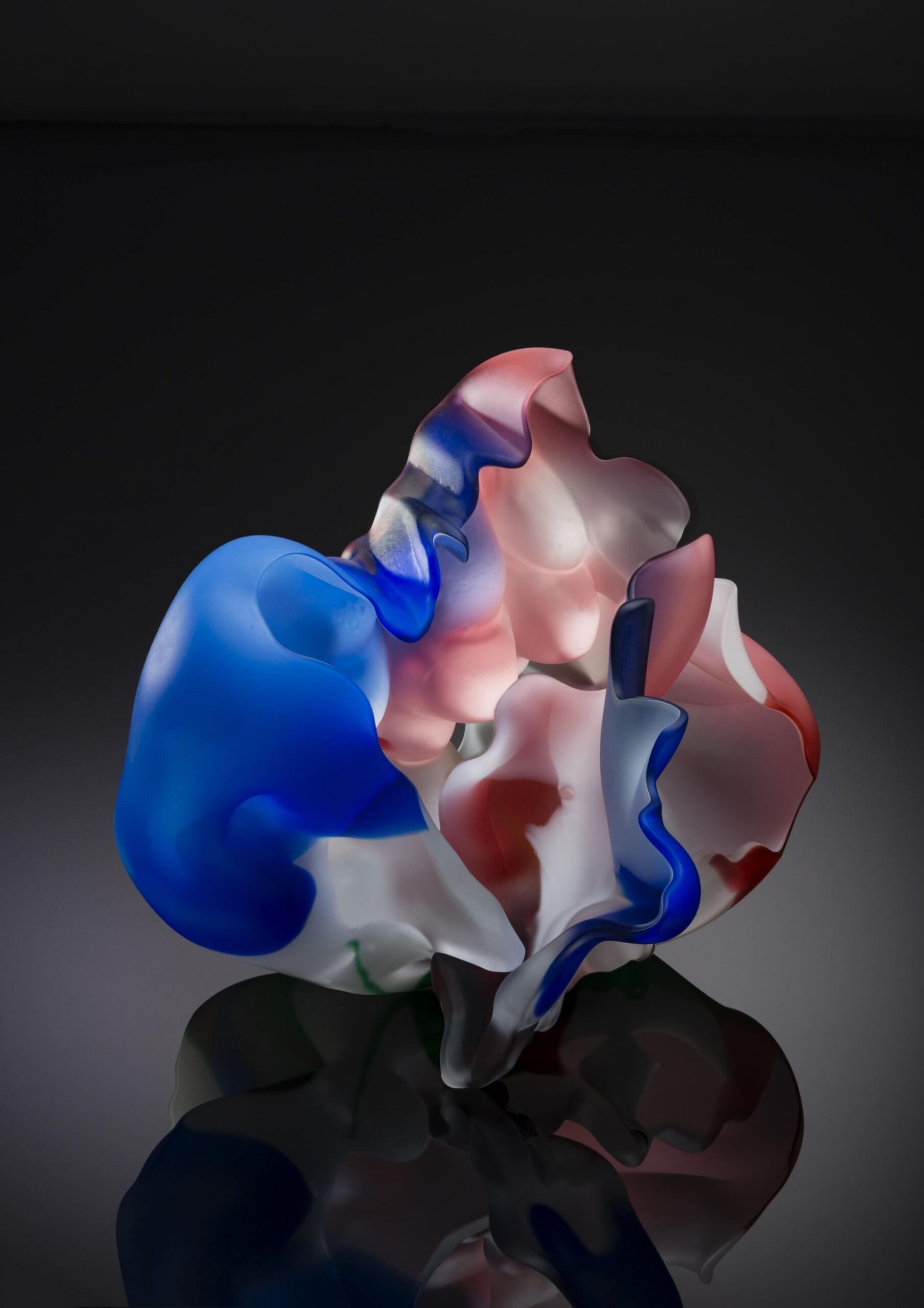

This collection forcefully advances the argument that abstract art can indeed be stunningly beautiful (incidentally, the FIA has some impressively accessible abstract art across all genres). The billowing forms of Marvin Lipofski are colorful abstractions reminiscent of Georgia O’Keefe flowers, but rendered in three dimensions. And staple to any collection of contemporary glass are the works of Chihuly; here, a set of his characteristically biomorphic bowls nestle into each other somewhat like Matryoshka stacking dolls. Works like these can easily serve as a gateway-drug into the world of abstraction for those who aren’t especially fond of abstract art.

Acid-polished blown glass Dimensions: 15 × 21 3/4 × 16 1/2 in. (38.1 × 55.2 × 41.9 cm) Courtesy of the Isabel Foundation, 2017

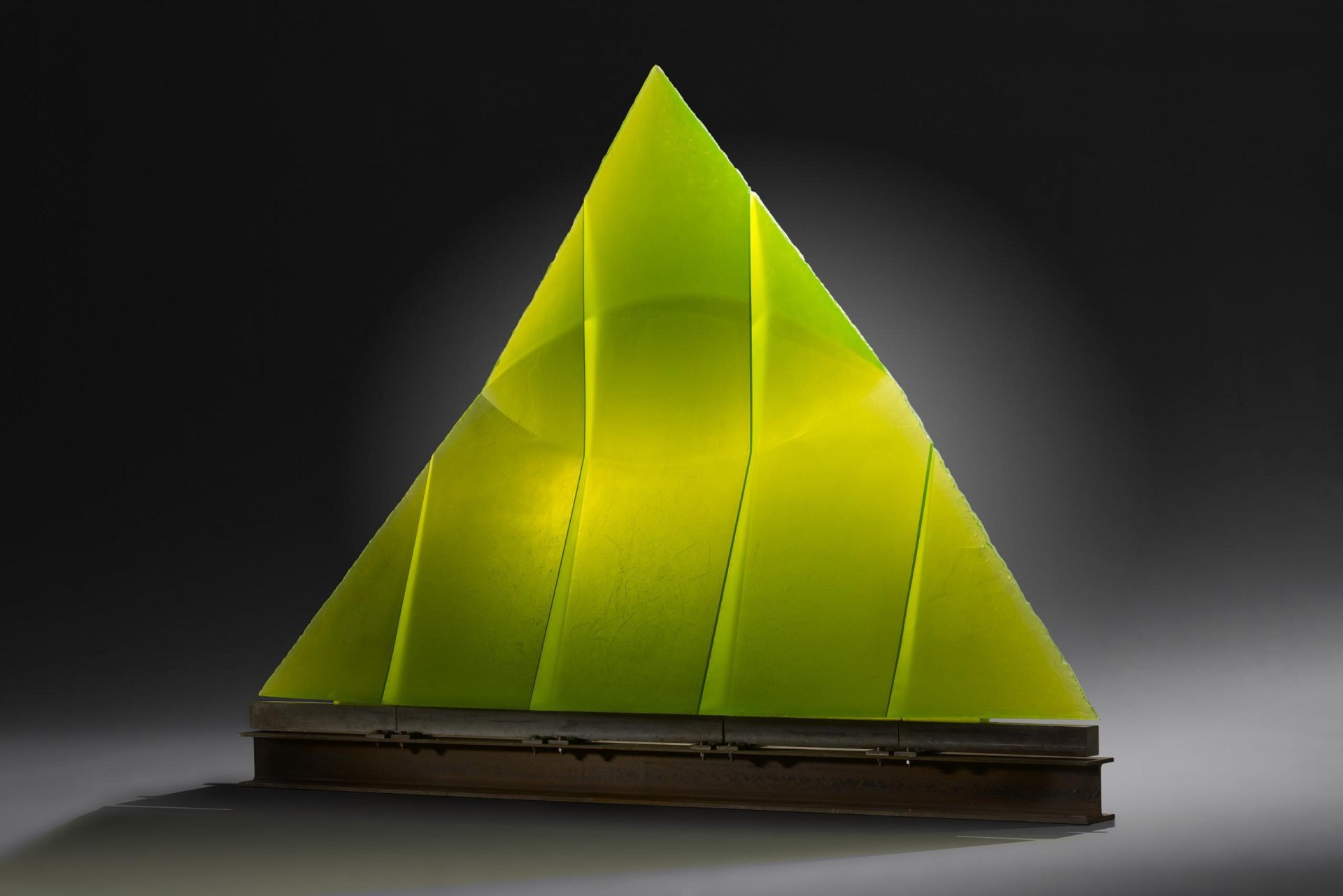

Many of these works are from Eastern Europe, a testament to the region’s history of glassmaking which stretches back to the Renaissance. Surprisingly, even while Communism exerted its dampening effect on the arts, glass artists were comparatively immune from restrictive policies, since the authorities didn’t think glass art had any subversive potential. The abstract works of Stanislav Libensky and his wife Jaroslavia Brychtova are a foil to state-sanctioned Socialist Realism, triumphantly making the case for abstraction and self-expression. The monumental scale of their collaborative Green Eye of the Pyramid helps to situate this work a visual anchor for the collection.

Cast, cut and polished glass, I-Beam pedestal, Dimensions: 82 1/2 × 113 × 29 3/4 in., 2000 lb. Courtesy of the Isabel Foundation, 2017

None of this is currently on view to the public, of course, but it will be eventually. In the meantime, the FIA has done an excellent job of digitizing its collection. Viewers can browse an online catalogue of art from the museum; one page offers selected highlights accompanied with audio guides, making the experience more informative and satisfying than simply clicking through pictures online. The Contemporary Glass page currently offers a catalogue of the FIA’s glass collection, and most works are accompanied by information about the artist. The FIA also produced a fine print catalogue of its glass collection, replete with beauty-shots of each work that fill the entire page, and occasionally spill onto a second.

Centuries ago, Abbot Suger, the mastermind behind the French Gothic style, famously referred to the light that passes through stained-glass as Lux Nova, or transformed, heavenly light. Best, of course, to experience its magic in person. But not all is lost in translation when viewing glass online. Many of these works are at their best when tactfully backlit by soft light, an effect that the luminosity of the computer screen almost seems to replicate. So until the FIA is able to safely open its doors to the public again, do take advantage of the chance to browse its glass collection which has been placed online in its entirety, and, of course, is completely free of charge.

Installation View, Courtesy of the Flint Art Institute

Glass Exhibition at the Flint Art Institute. The FIA staff is working hard to get ready for the moment when they will be able to open their doors to welcome you to visit the galleries. Although they haven’t set a date yet, FIA is preparing for the opportunity to reconnect with you while practicing social distancing throughout a virus free facility.