Vincent Castagnacci: Quarry Echoes & Wanderings at the Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center

An installation view of Vincent Castagnacci: Quarry Echoes & Wanderings, which will be at the Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center until April 21.

Vincent Castagnacci: Quarry Echoes & Wanderings (1984-2021) is an intriguing tour through abstraction with a distinctly geometric cast, and will be up at the Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center through April 21. Castagnacci, the University of Michigan’s Arthur F. Thurnau Professor of Fine Art Emeritus, takes rationalism’s standard forms – squares, semi-circles, triangles and parallel lines – and twists them to his liking, confounding conventional expectations.

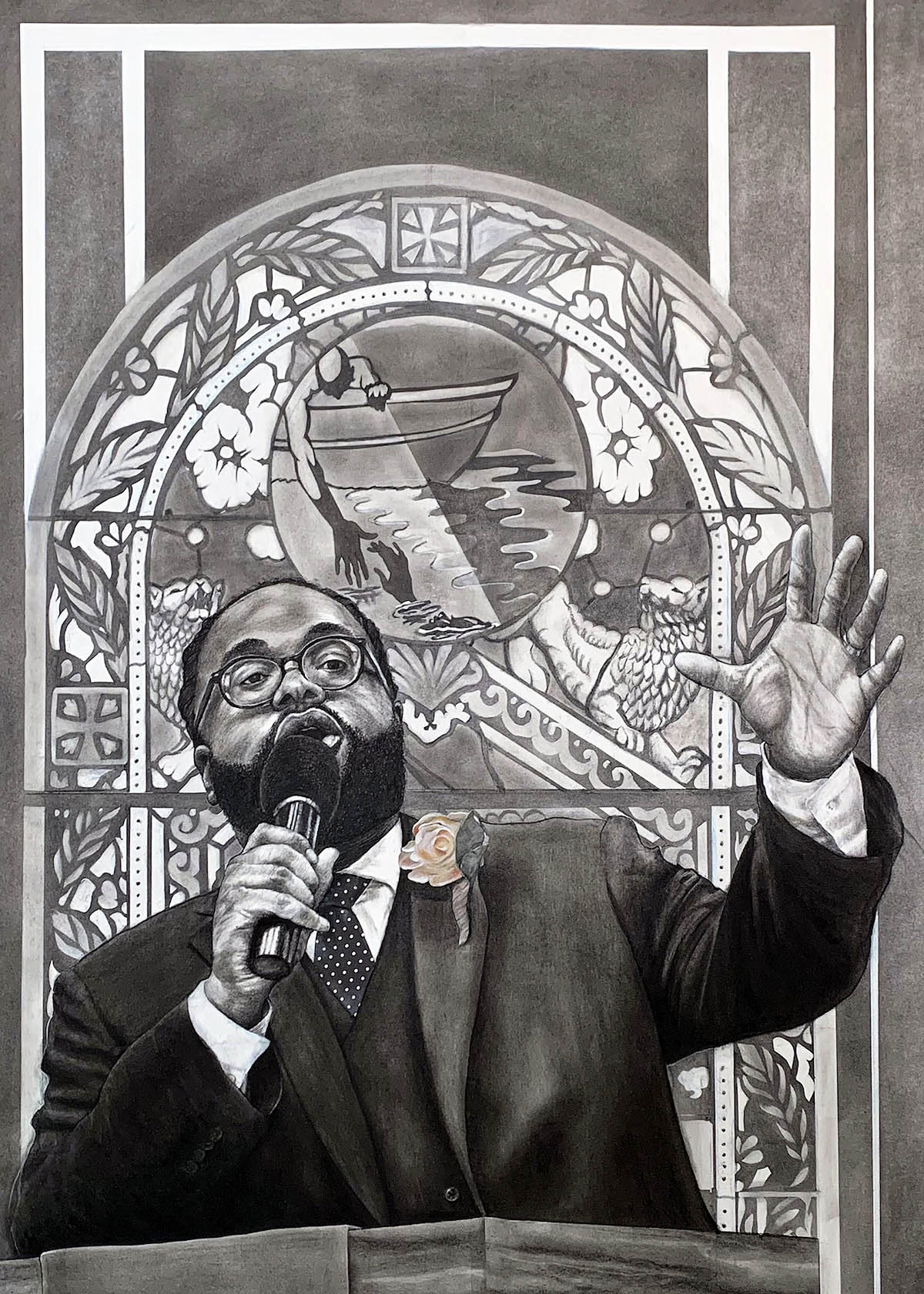

Take, for example, the large, black and white VII.06 – 19.VIII.06. This series of interconnected squares, some scored in dull red, has an undeniable momentum, and appears to be in the process of levitating from left to right. The piece is spare, and looks like it was sketched rather quickly — doubtless an illusion. In some respects, you could say it resembles a series of matchbooks or, more intriguingly, the sort of early renderings architects jot down to see how different building volumes will interact with one another.

Vincent Castagnacci, VII.06 – 19.VIII.06, Charcoal pencil, Dry pigment, Gesso, 2007.

But Castagnacci, who maintains a studio locally in Pinckney and one in Gloucester, Massachusetts, attributes the genesis of his work to the geometry of natural landscapes, not man-made forms. In his artist’s statement Castagnacci cites the “coastal topography of Cape Ann” around Gloucester, with its boulder-tossed beaches and craggy granite bluffs, as both inspiration and defining aesthetic undergirding his point of view. So perhaps VII.06 – 19.VIII.06 is less architectural and more a tectonic rendering of rock and hillside.

Castagnacci, who arrived at the University of Michigan in 1973, studied at the Boston Museum School at Tufts University, then followed that with both a B.F.A. and M.F.A. from Yale. He was most recently a Mellon Fellow at Kalamazoo College, and has also been a visiting artist at the American Academy in Rome. His artistic interests range widely. Encouraged by the dean of the U-M School of Art & Design to reach across academic boundaries, Castagnacci collaborated with percussionist and composer Michael Gould in a five-year project that in 2005 yielded Into the Quarry, an installation celebrating the convergence of art and music in space and time.

Annie VanGelderen, BBAC president and CEO, praised Castagnacci’s “incredible body of work, one that demonstrates both restraint and a thread connecting through the years.” The pieces on display, she added, “unfold in geometric presentation, whether with painting, drawing or printmaking.”

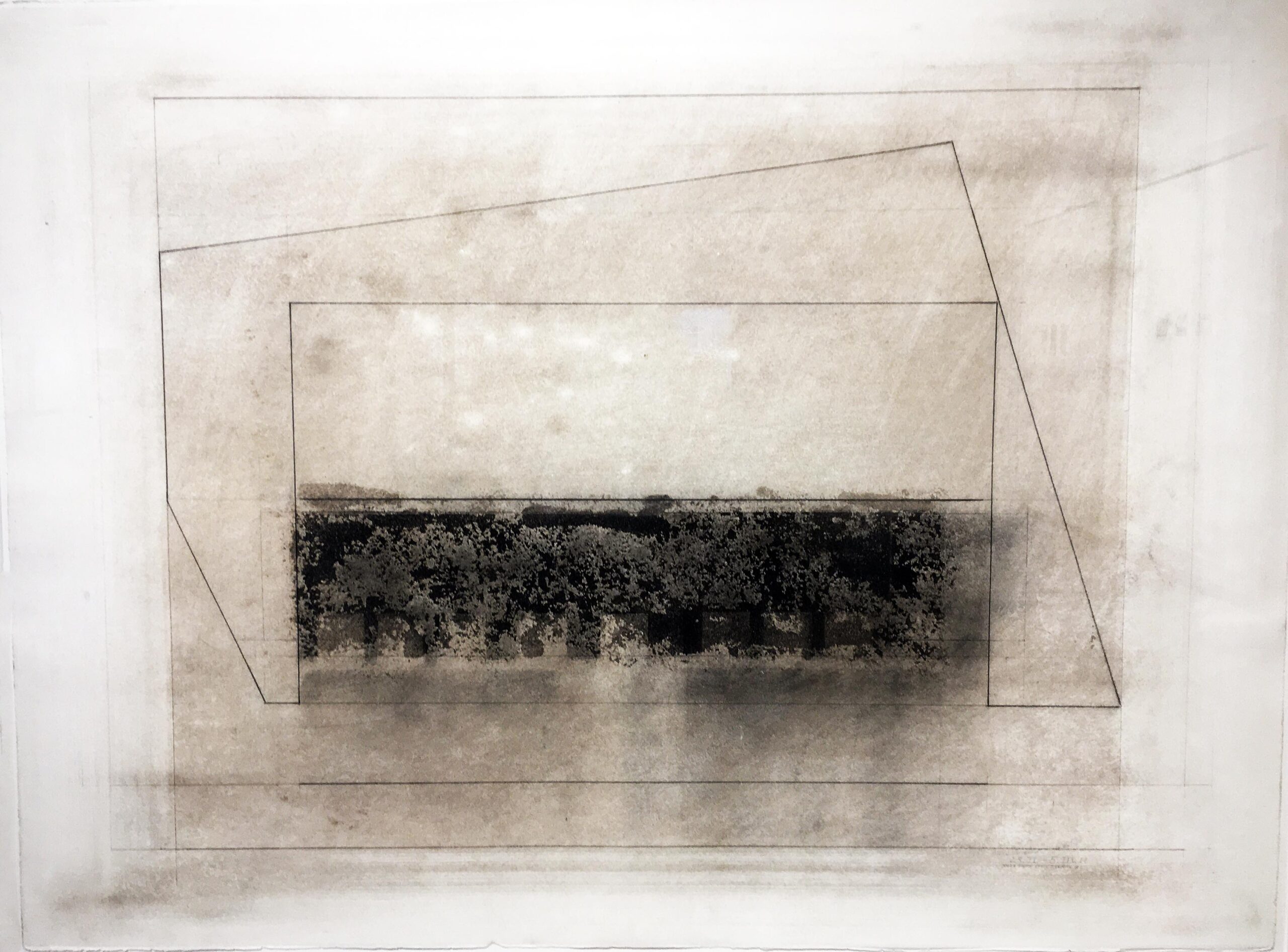

Vincent Castagnacci, Rome: III.25.80-20.VII.12, Oil and chalk, 2012

The contrast between Castagnacci’s spare black-and-white drawings and his colorful, texture-rich paintings, which pop like exclamation points, is part of what gives this exhibition its juice. The oil-and-chalk Rome: III.25.80-20.VII.12 offers a pleasing contrast to the “simpler” works, an essay in repetitive verticals that progress in color from dull, mottled shades of powder blue to nightingale brown. It’s a remarkably textured exercise. The effect, one viewer suggested, reminded her of the raw material for blue jeans, though for this visitor, it read more like a satisfyingly weathered, corrugated metal wall in tones of grayish-blue.

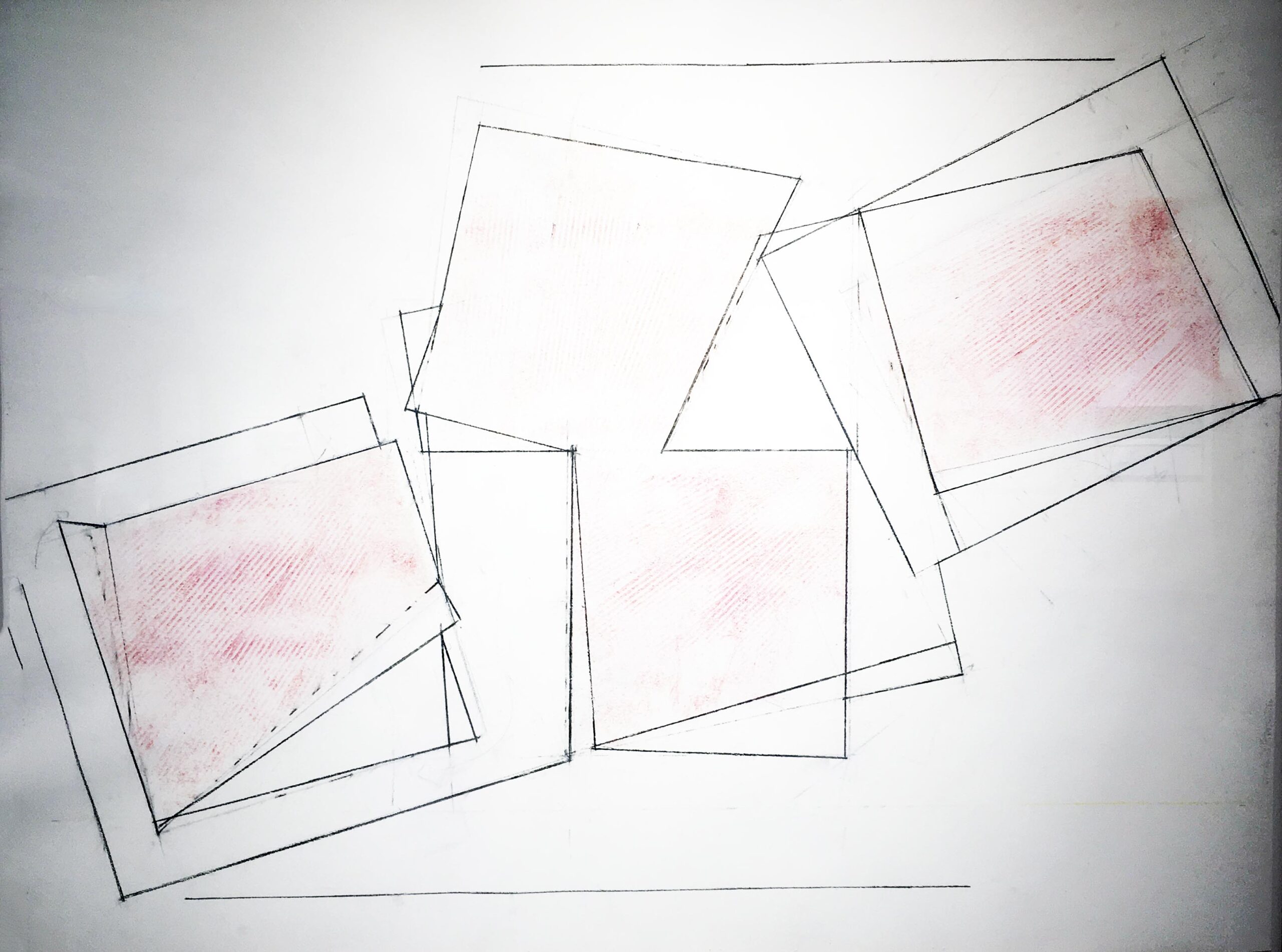

There are a number of absorbing essays in squares and rectangles here, including the austere, geometric 23.II-5.III.11#1, comprised of three or four superimposed frames. Two are squarish, while a third contained within the others tilts and lists into its fellows, like an unsteady parallelogram. Rendered in surprisingly rich tones of charcoal and ash, 23.II-5 almost amounts to a monochromatic color study, animated by a densely textured black rectangle that anchors the work and gives it its mesmerizing depth.

Vincent Castagnacci, 23.II-5.III.11#1, Oil, 1997

23.II-5.III.11#1, is a warm, color-saturated canvas in distressed shades of barn red, scored here and there with verticals and horizontals that almost suggest inset panels in a door. In some ways this lush, resonant piece feels thousands of miles from the Massachusetts coast and Cape Ann. In its warmth and seemingly ancient appearance, it calls up the Mediterranean more readily than the North Atlantic.

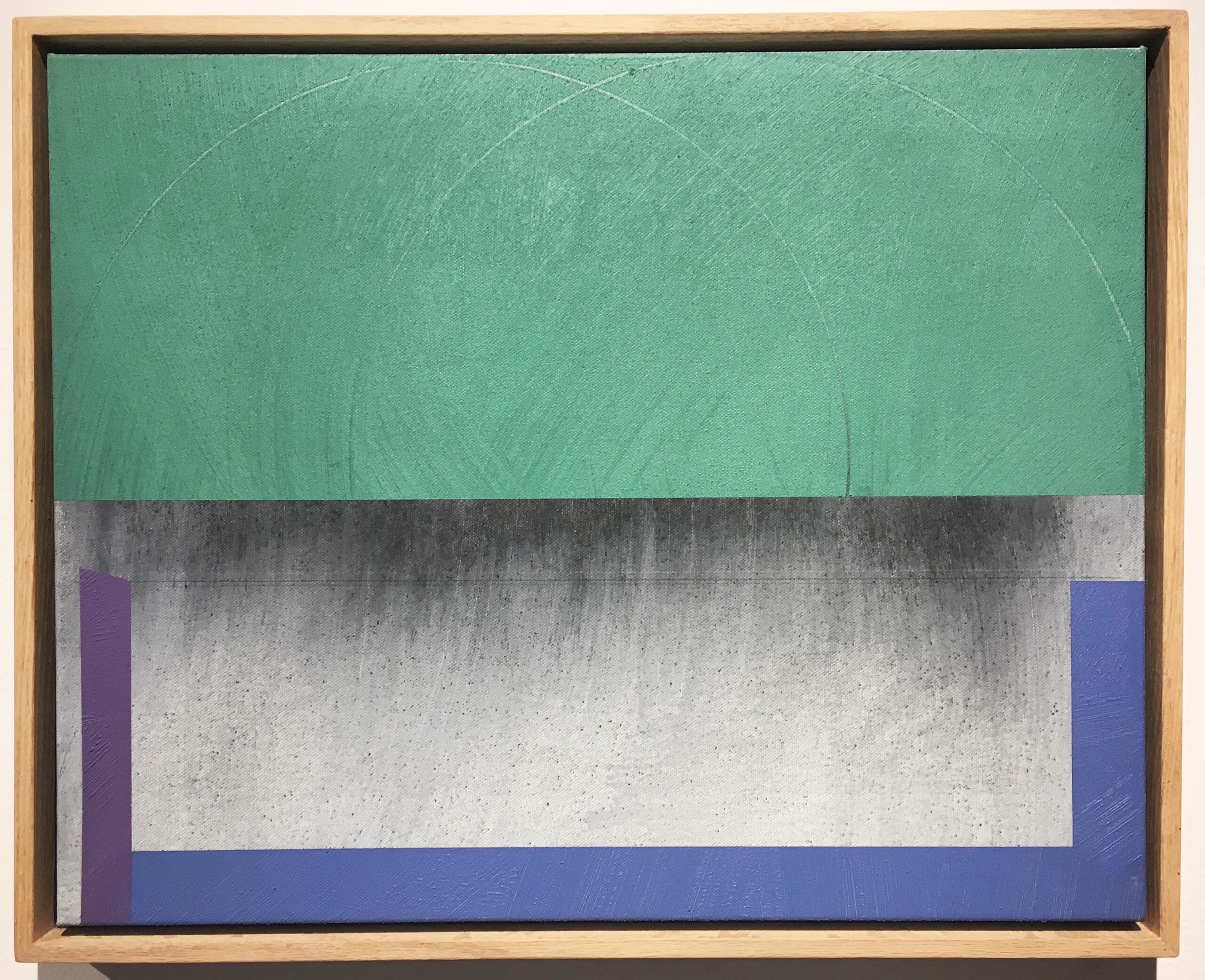

Finally, 7-11.X.19, one of the handsomest pieces on display, is a highly formalistic, acrylic-and-ash color study in green, periwinkle, lavender and shades of gray edging into black. Part of the charm of this composition is that while the strong colors all seem to occupy the same plane, the dark gray they frame looks downright three-dimensional, as if that quadrant of the canvas were receding several inches from the rest of the work. It’s an absorbing design that tiptoes to the edge of trompe l’oeil.

Vincent Castagnacci, 7-11.X.19, Acrylic, Ash, 2019.

Get ready for something completely different when you pass from Castagnacci to the adjacent gallery housing Christine Welch’s Nature of Things, also up through April 21. The first work that greets you is a “wasp comb,” very much like a honeycomb, framed in a box atop a bed of greenish-yellow leaves. Wasp nests figure large in this unusual exhibition. Indeed, perhaps the most-striking elements are the several large paper-wasp nests hanging from the ceiling like so many cocoons of prodigious size.

Welch says she’s dazzled by our connection to nature, and in particular with the structural similarities beneath the surface of any number of natural forms, the human body included. With Nature’s Seamstress, she constructs a mannequin out of a clothing designer’s dress form, in a skirt made from large sheets of wasp paper, and a round wasp comb for a head. Completing the ensemble are two strands of large, brown seed pods strung together into a necklace.

The combination of oddball elements at first sounds like it might be amusing, a bit of a visual joke, but the actual assemblage is far more sobering than humorous, with suggestions of a totemic form constructed by a people far more intimate with the natural sphere than those of us in the “civilized” world.

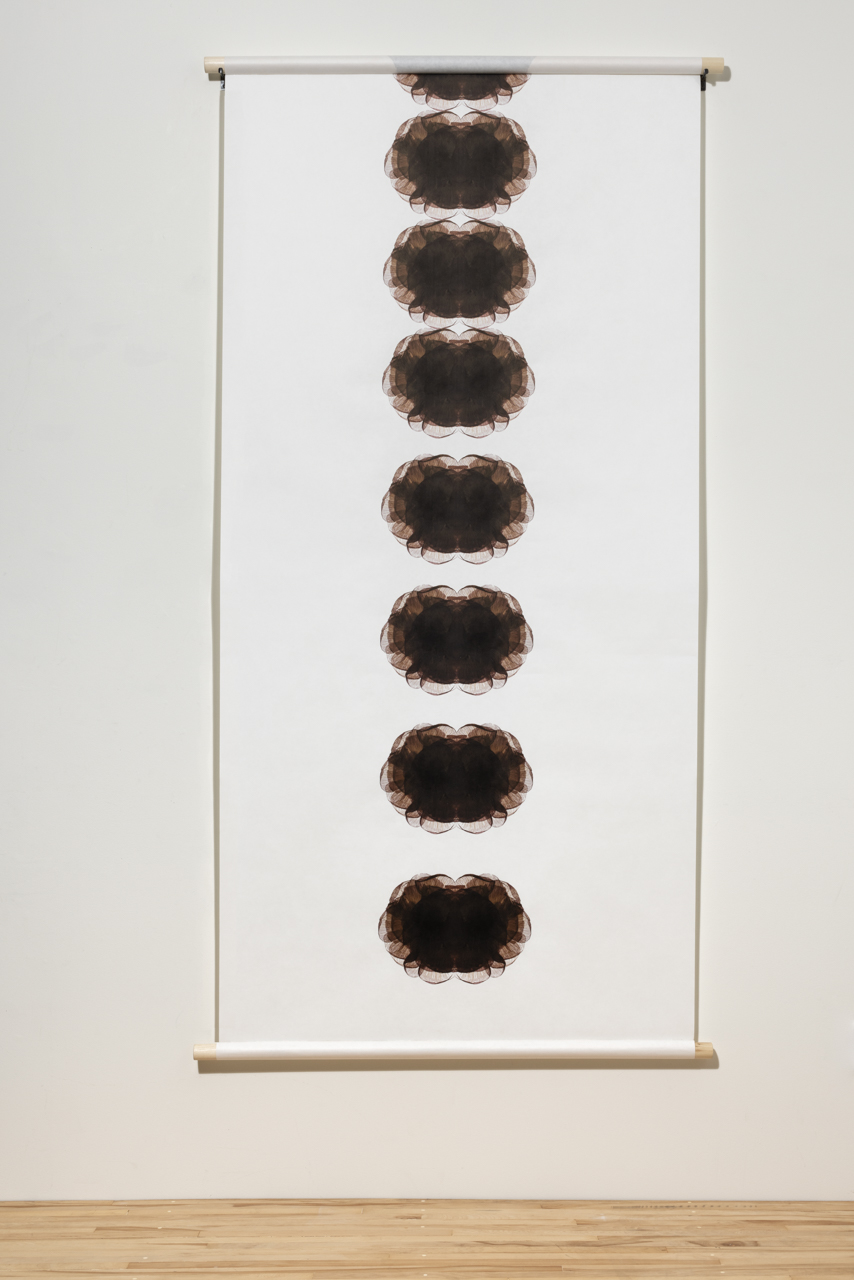

An installation view of Nature of Things: Christine Welch, at the Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center through April 21.

Christine Welch, Hive, at the Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center

Both Vincent Castagnacci: Quarry Echoes & Wanderings (1984-2021) and Nature of Things: Christine Welch will be up at the Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center through April 21.