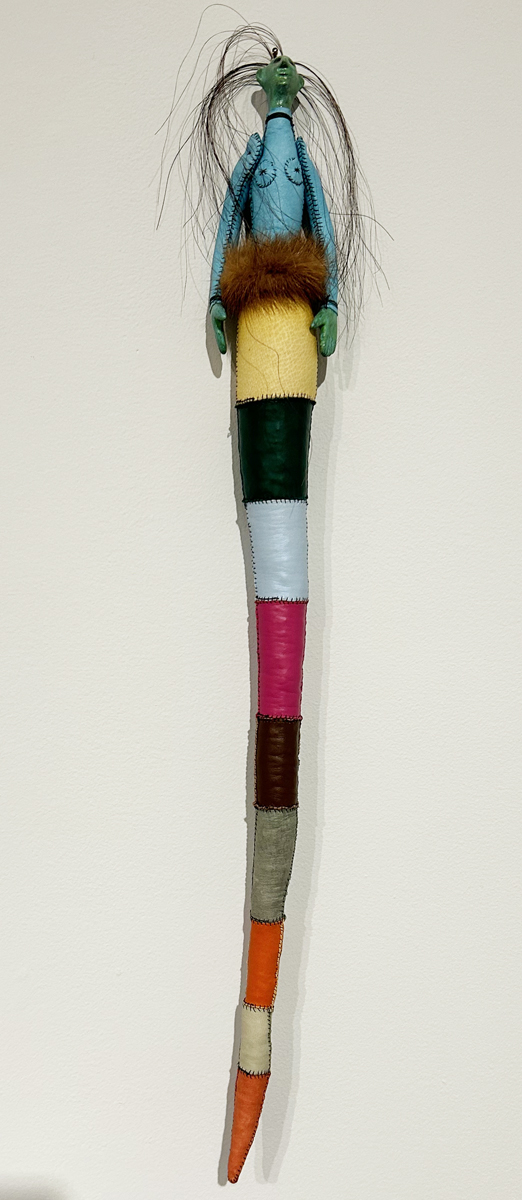

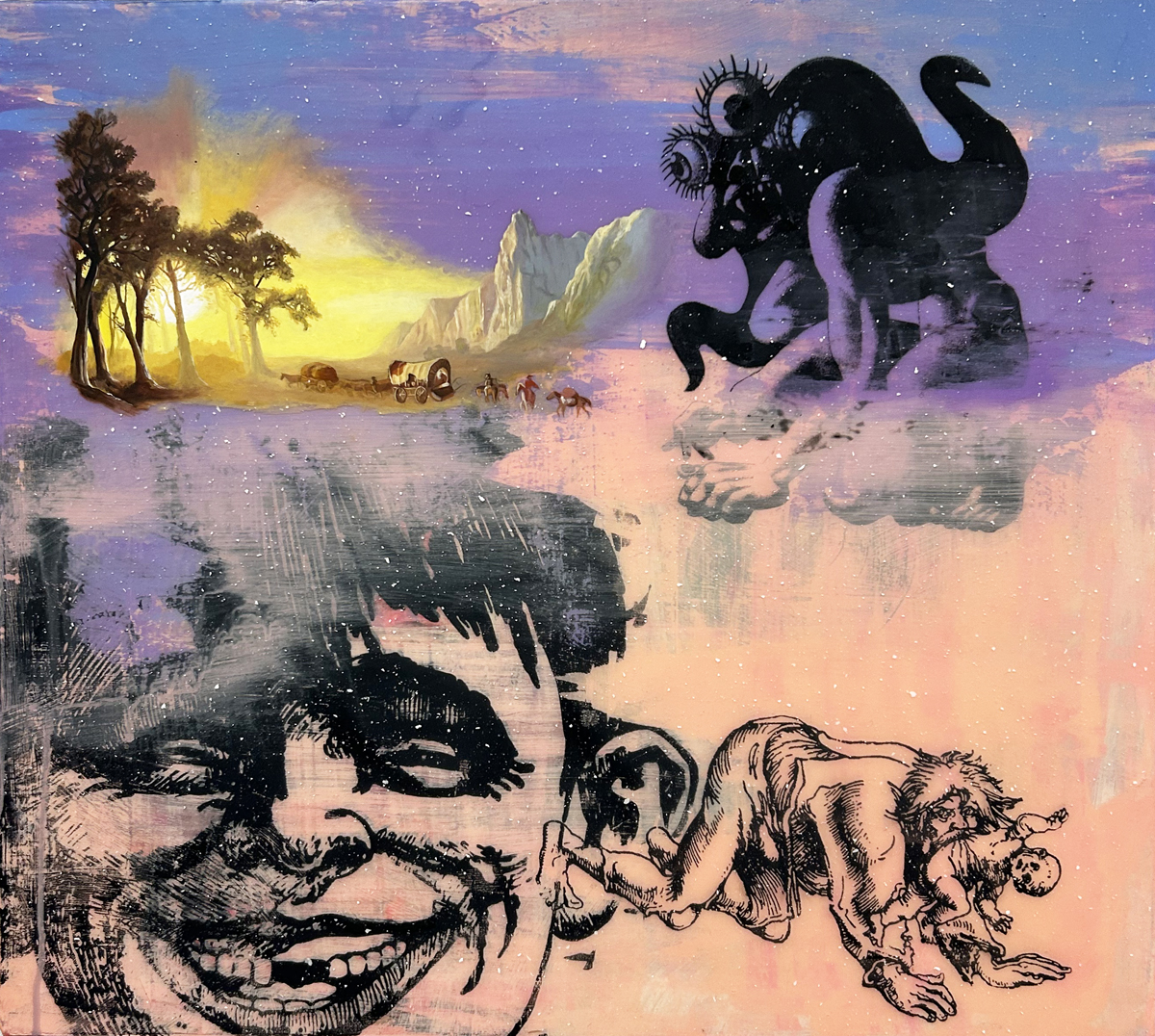

Islands Inlands: James Collins at Matéria Core City previously Simone DeSousa

The series of paintings on display at Matéria Core City embodies the most recent explorations of Detroit-based artist James Collins. Since the onset of his career in the late 1990s, Collins has been working with the harmonies and disharmonies of oil and acrylic paint on canvas. His dedication to the study of these materials has resulted in an array of abstract compositions that align his work with minimalist philosophy from the 1960s, bringing it into the present day.

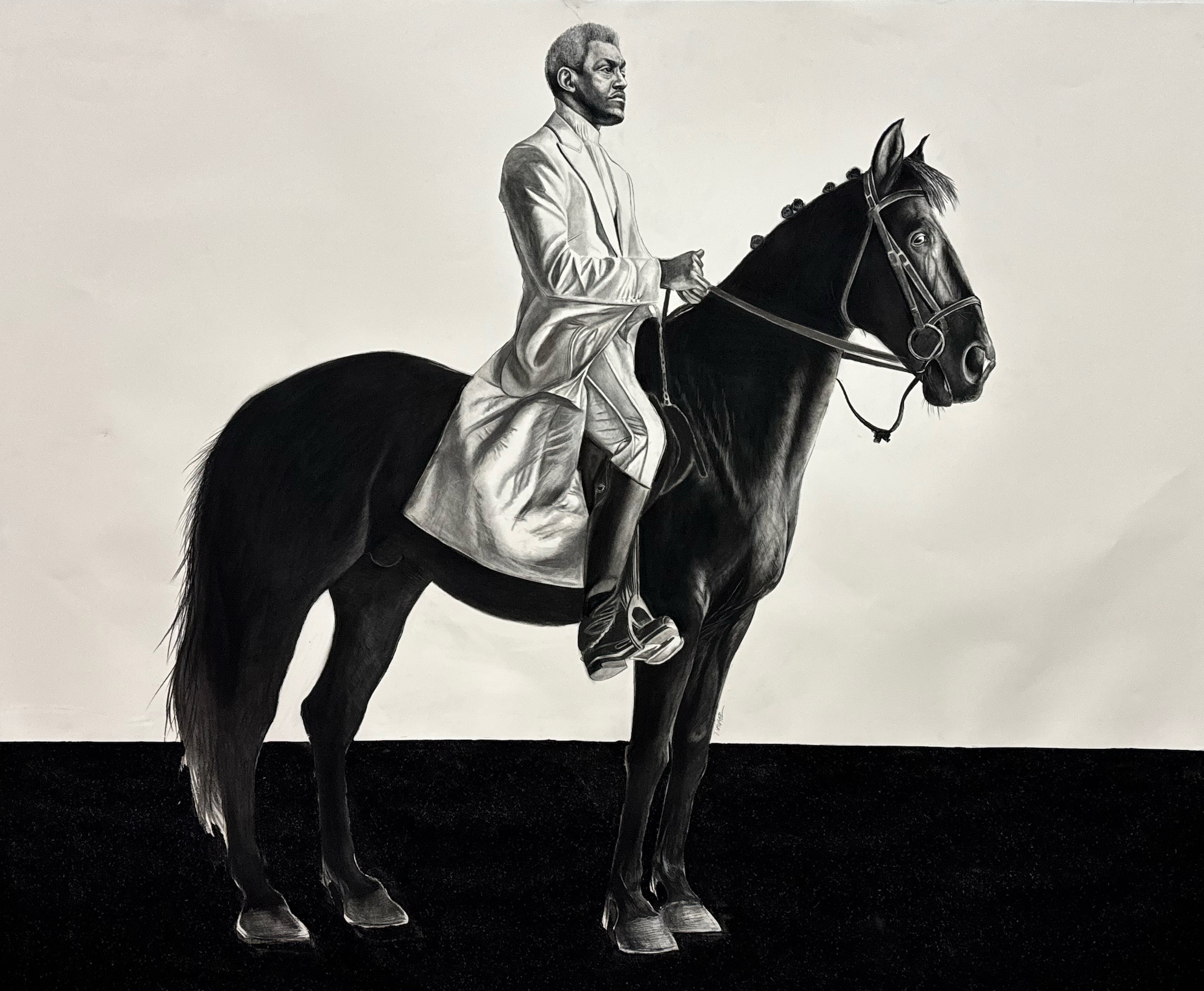

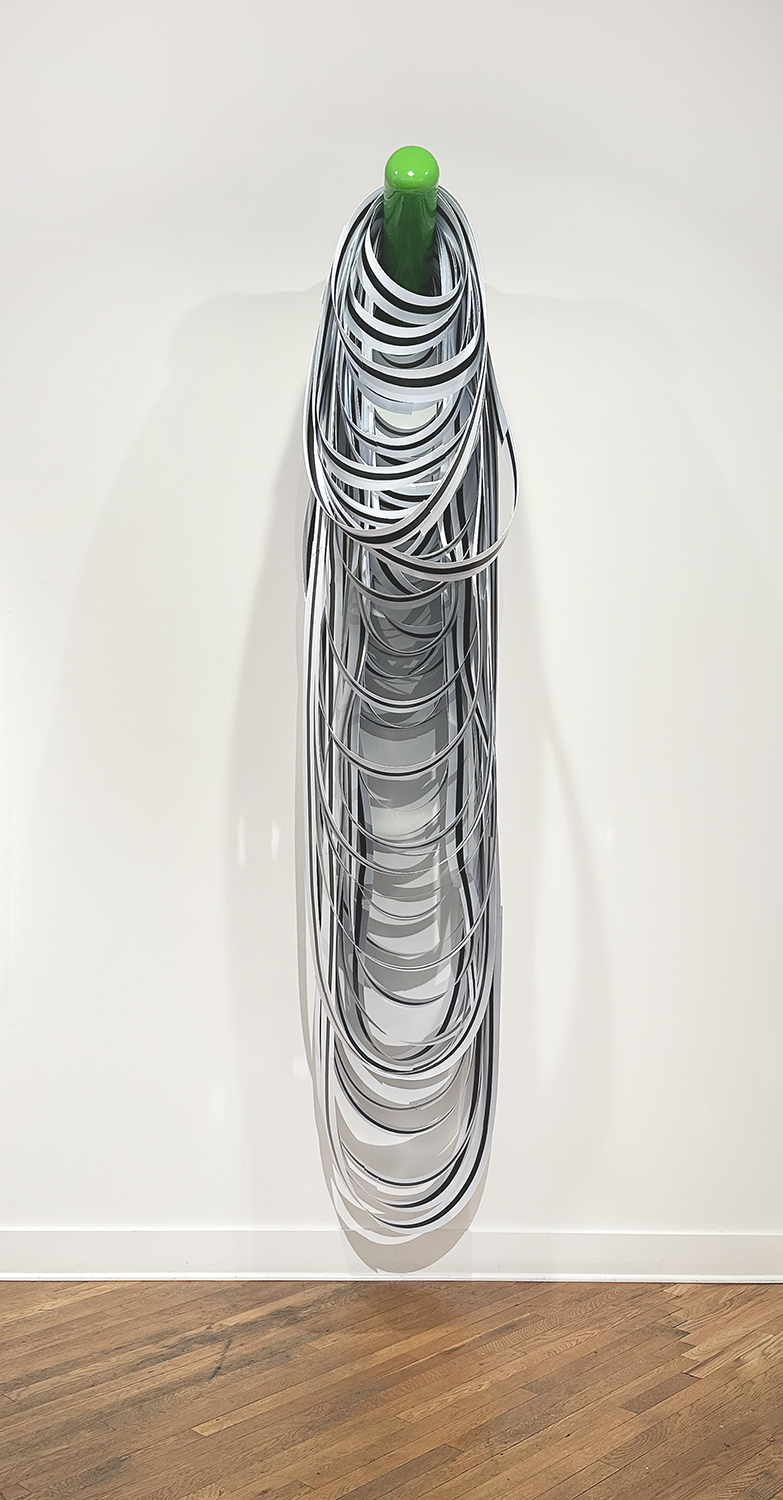

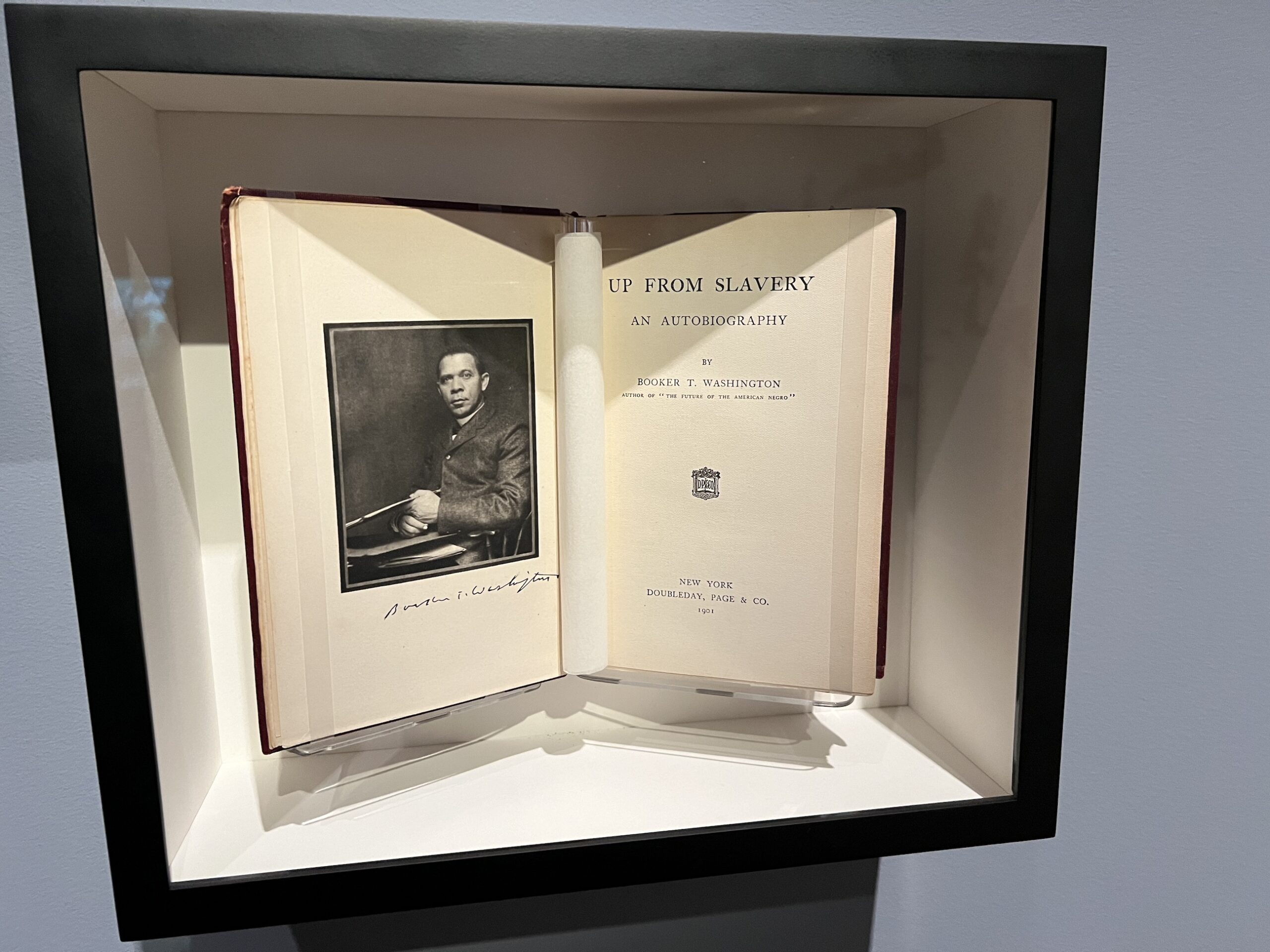

James Collins, installation of Islands Inlands at Matéria Core City, 2023, All photos courtesy of Matéria Core City.

Minimalism emerged as a creative movement in New York City as a reaction to the traditional expectations of artists to be messengers of narrative or conduits of expressive thought. Many artists of the time became bored of methods used in abstract expressionism and other preexisting movements. Setting out to challenge the concept of romanticism in art, artists like Donald Judd, Agnes Martin, John Cage, and Meis van der Rohe simultaneously worked to explore material abstraction and the reduction of meaning in creative production. This resulted in the blurring of boundaries between painting, sculpture, architecture, writing, and music that became profoundly revolutionary.

James Collins, installation of Islands Inlands at Matéria Core City, 2023

Frank Stella, one of Minimalism’s founding painters, was famous for saying “what you see is what you see,” and in this statement, summarized the movement’s embrace of the literal properties of any object presented as art. Size, form and the work’s relationship to its surrounding environment held precedence over symbolism and emotion. Artists used prefabricated forms and geometric shapes to reduce the influence of the artist’s hand and promote an exploration of the form or process as subjects in themselves.

James Collins, installation of Islands Inlands at Matéria Core City, 2023

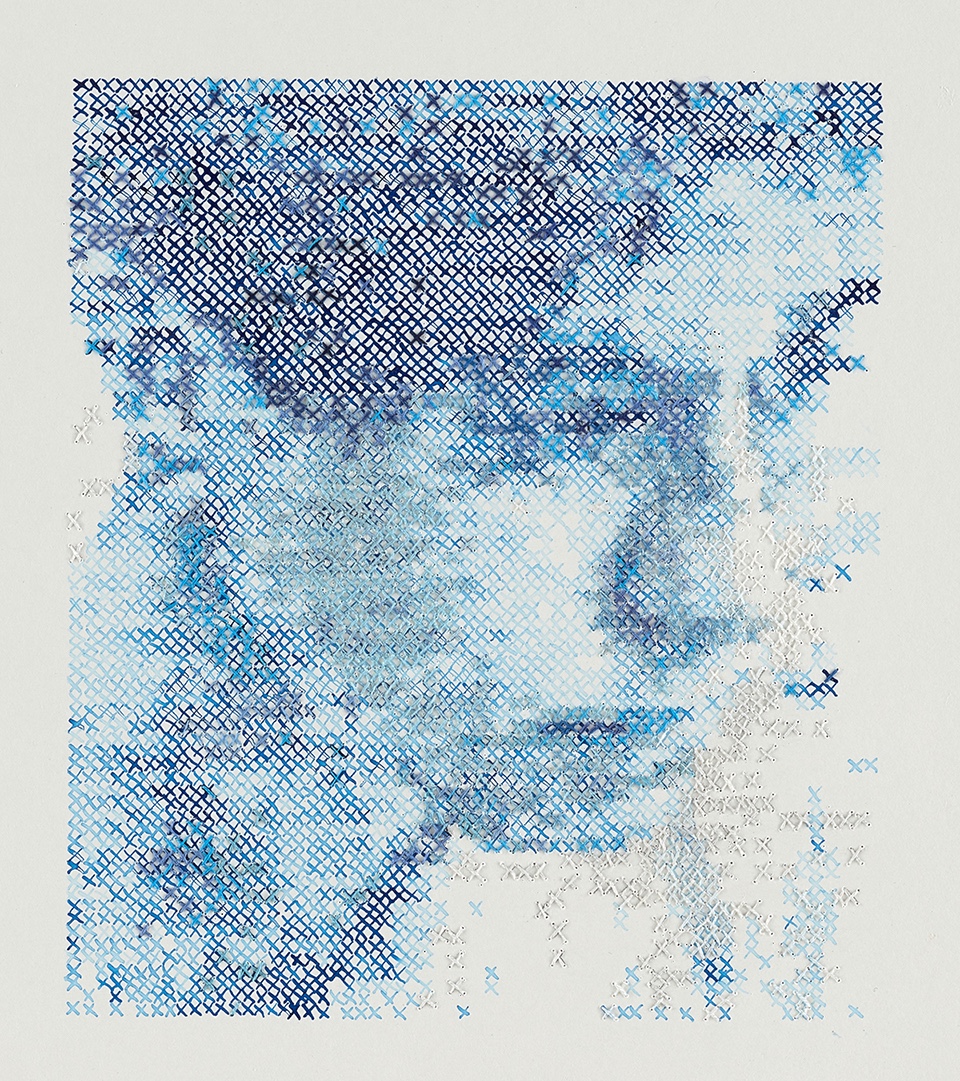

Naturally as a painter, the presence of the rectangle is prominent in the artist’s practice, but in addition to this geometric form that mirrors the surrounding architecture, James Collins’ “employment of the process as content” sustains traditional minimalist characteristics. The exhibition text underlines this sentiment through descriptions of the household items used to produce these images that resemble detailed aerial views of natural landscapes. However, despite us learning about what he used to make the paintings, the details of how he used them remains a mystery. Viewers have the opportunity to engage in a phenomenological experience that challenges perception through direct interaction with the work. From afar, many of them seem to be photographic prints only to reveal intricate applications of paint upon closer analysis.

James Collins, installation of Islands Inlands at Matéria Core City, 2023

Illusionism, dating back to ancient times, is an artistic tradition that attempts to mimic three- dimensional forms on two-dimensional surfaces. Artists of this practice have used color and perspective to mimic reality to such a degree that it could deceive any eye that sees it. In fact, there is an old myth from the elder Pliney in 464 BCE Greece that tells a story of the artist Zeuxis painted grapes so realistic that the birds attempted to eat them right off the wall. The occupancy of illusionism in these twelve paintings by Collins is carried forward as an effect achieved through the artist’s exploratory approach to the medium of paint. Texture is used to suggest space on these flat surfaces the way line was used to imply depth in his previous works. What is interesting about the body of work is its tendency to oscillate between an illusionist and minimalist approach, both of which are inherently opposite of one another. The sophisticated use of color in them further stimulates our tendencies to make sense of abstract

forms based on optical likeness, but in the end, time spent with the work becomes a moment of visual play that forgoes definition due to its high degree of investment in abstraction.

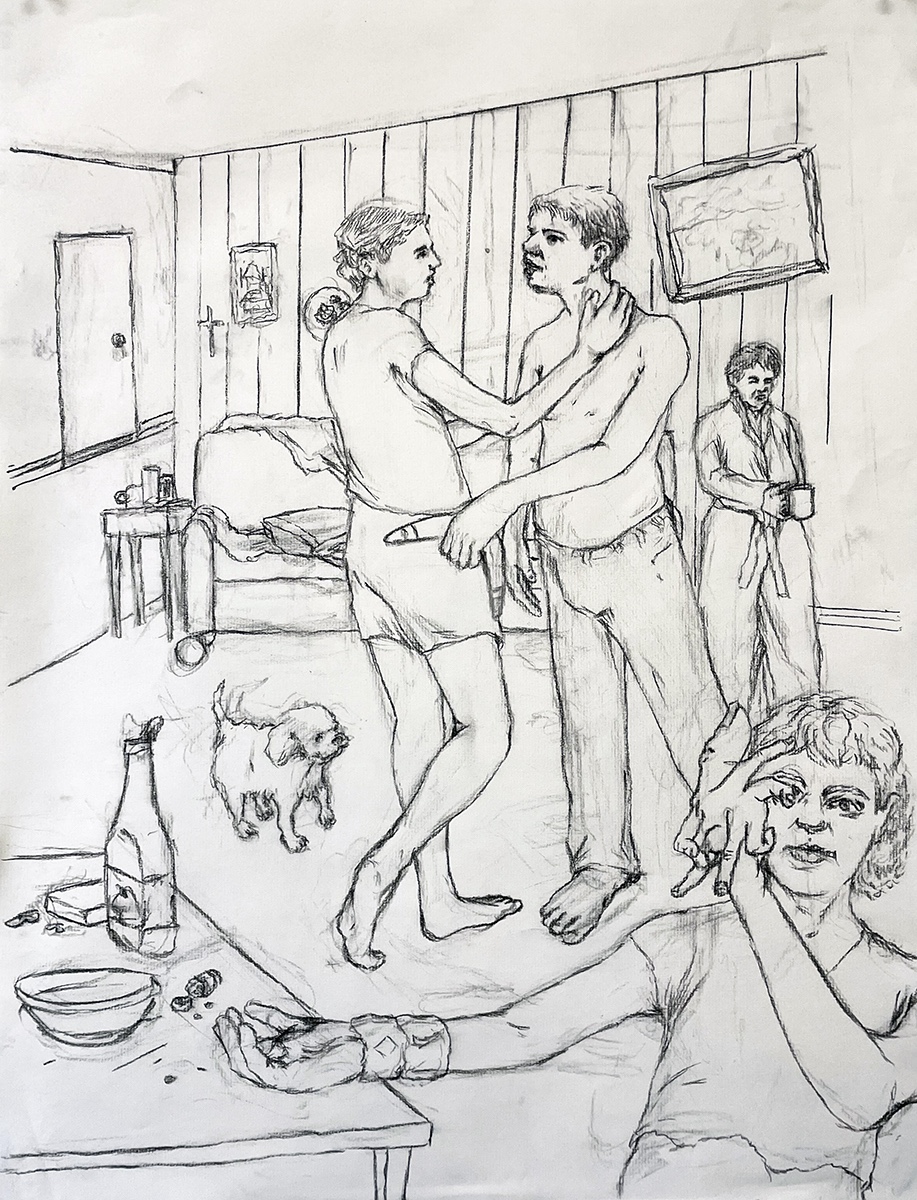

Photograph of the artist with his painting, 2023, photo: Matéria Core City

Each painting in Islands Inlands utilizes patterns of sharp lines that mimic the visual qualities of arteries found in nature. Blood vessels, root systems, and canyons become visible through contrasts in color and tone, and these two-dimensional simulations are achieved through the delicate chromatic gradients that render shadows into these micro or macro pathways. Small hints to inspire this read occur in titles like Here Come the Warm Jets, Points Beyond, Untitled (arquipelago #1) and Untitled (arquipelago #2). A denial of external references becomes present, however, through the majority of untitled works in the show, and it is again confirmed through the same textures having seemingly exploded into fragments on a few white canvases. The reduction of subjectivity is another marker of minimalist thought that emerges not only in limited visual elements but also in the sparseness of information provided to guide translation. Like many creative approaches in this postmodern era of art, minimalism continues to be investigated decades after its debut. Perhaps the reason it continues to be relevant amongst the wide scope of methodologies is its ability to provide an experience of open interpretation. It can be rewarding to locate meaning in such abstraction and the ambiguous nature of these minimalist compositions allow for a range of meaning as broad as its diverse audience.

James Collins, installation of Islands Inlands at Matéria Core City, 2023.