Detroit Style: Car Design in the Motor City, 1950 – 2020 at the Detroit Institute of Arts

Installation: counterclockwise, Firebird III, General Motors, 1958; 300C, Chrysler Corporation, 1957; Le Sabre, General Motors, 1951

As a visitor arriving at the Farnsworth Street entrance of the Detroit Institute of Arts to take in “Detroit Style: Car Design in the Motor City, 1950 – 2020,” you’ve just begun your journey. After entering the Farnsworth doors of the South Wing of the building, one begins a colorful and eye-catching hike across the width of the museum. The tour passes through the hallowed halls and treasure laden galleries of the Institute until reaching the North Wing and the now deinstalled modern/contemporary galleries and the exhibition entrance. There, a wide doorway (definitely not a columned portal) leads into the first show-stopping gallery of “Detroit Style.” Unlike any other gallery in the DIA, arrayed before you is a breathtaking trio of sleek, shiny automobiles seemingly floating on an expansive white vinyl plinth: a silvery gray Firebird III (General Motors, 1958), a pristine white 300C (Chrysler Corporation, 1957), and a lush misty blue Le Sabre (General Motors,1951). Their elegantly understated hues allow the clean lines, crisp edges and creases, wings, fins, and upswept taillights to protrude and project into space. After all, as a curator once wittily claimed, “Automobiles are hollow, rolling sculptures.”

This, the first and largest gallery, focuses on the 1950s in an exhibition that unfolds chronologically decade by decade. Organized and overseen by DIA curator Benjamin Colman, twelve cars in all are displayed, four from each of the Big Three manufacturers. (And, tactfully, a different car graces three distinct covers of the indispensable catalog–in red, silver, or blue, your choice.) Each of the sequential galleries showcases one or more concept and/or production vehicles. In addition to automobiles, the show offers design drawings, archival photos, paintings, a sculpture, and short videos in which designers discuss their works. (Access the videos at end of this text.)

In the opening gallery, for instance, devoted to the 1950s and presenting the cars described above, a drawing by Art Miller, Rendering of Automobile Interior (1952), features a cutaway view of a gleaming red and black interior and the startling sight beyond the opposite window of a tiny, low flying jet zooming by in the distance, an apt reflection of the influence of aircraft forms on auto design then as well as of the au courant lingo of the 50s: “The Forward Look.”

Installation: foreground, Corvette Stingray Racer, General Motors, 1959; background, Edward Ruscha, Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas, oil on canvas, 1963

In one of the subsequent galleries addressing the 1960s, a Corvette Stingray Racer (General Motors,1959) is backgrounded by Edward Ruscha’s Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas (1963). Sharp, crisp lines exaggerating length and emphasizing edges and creases earmark both objects. The iconic red, white, and blue gas station, defined by thrusting diagonals that recede into infinity, is silhouetted against a dark sky with criss crossing searchlights that highlight both the glowing filling station and silvery Stingray in the foreground.

Installation: left, Mustang, Ford Motor Company, 1967; right, Plymouth Barracuda, Chrysler Corporation, 1970; middle, John Chamberlain, Coo Wha Zee, painted steel, 1962

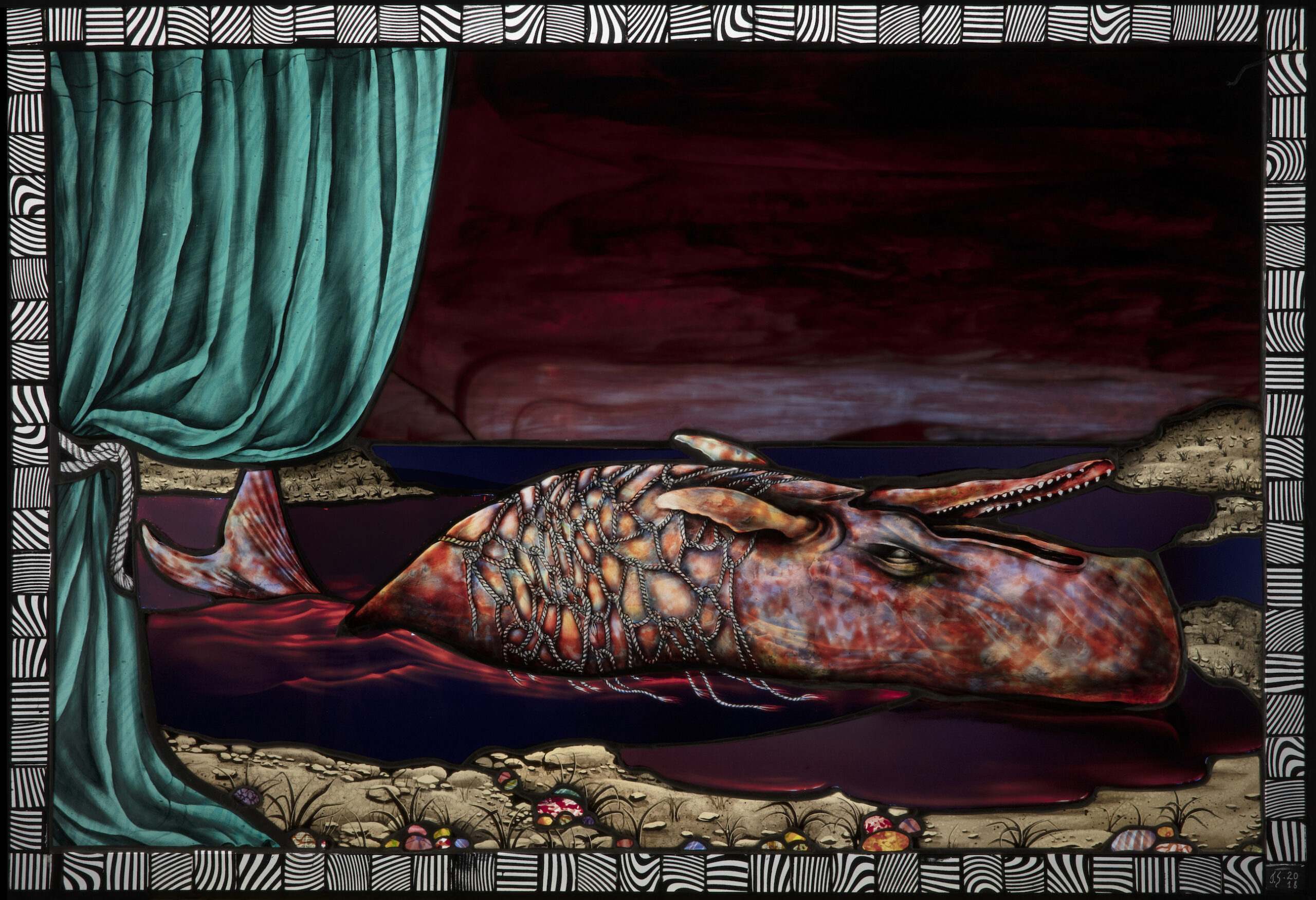

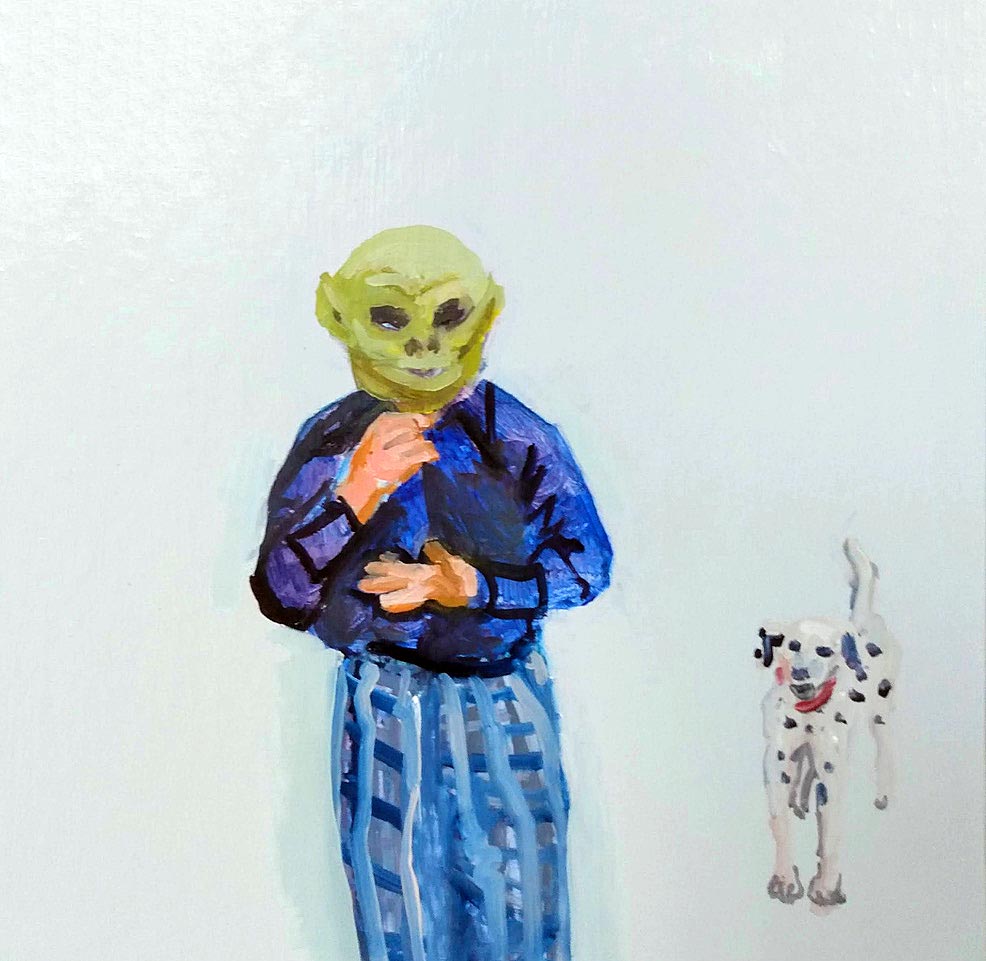

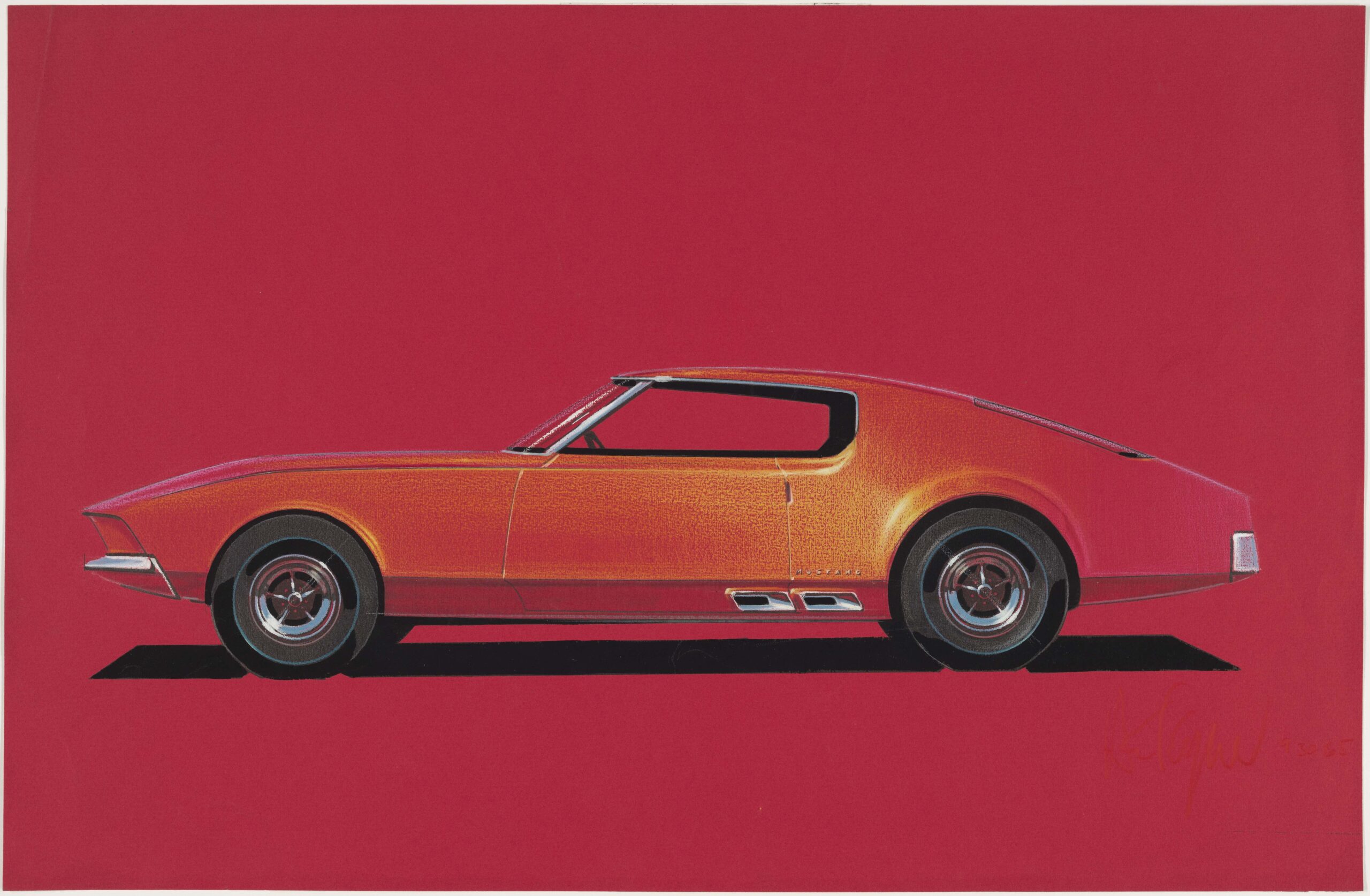

Moving further along into the 60s, two so-called pony cars, the Mustang ((Ford, 1967) and Plymouth Barracuda (Chrysler, 1970), enter the scene. Viewed head on, as here, these sporty, youthful, and spirited vehicles present contrasting hues, one gutsy black, the other flaming red, each with a broad, mouthy grille suggestive of a tense, one-on-one confrontation. Nestled between them is John Chamberlain’s brawny black and white sculpture, Coo Wah Zee (1963). Fabricated from discarded car parts bent and contorted into a tall, rough-edged abstraction, it is, as the title intimates, one “crazy” sculpture. Two drawings, the rakishly tilted 71 Barracuda Front End Facelift Concept (1968) by Donald Hood and Howard Payne’s smoldering Ford Mustang(1965)–a ripe orange body profiled on red paper–attest to the visceral appeal of these feisty, automative rivals.

Donald Hood, ’71 Barracuda Front End Facelift Concept, mixed media on vellum, 1968

Howard Payne, Ford Mustang, Prismacolor and gouache on red charcoal paper, 1965

Just beyond midpoint in the exhibition, rather like a palate refresher, the 4-door, aerodynamic Probe IV (Ford, 1983) comes into view. Its soft, pristine white hue, integrated forms, rounded corners, quiet, whispering demeanor, and four wheel covers minimizing the presence of tires and implicit speed, denote what one commentator described as a “wind cheating supercar.” Accompanying its calm presence are a number of fluid, ovoid renderings by Howard “Buck” Mook, Maurice Chandler, Taru Lahti, and Ken Okuyama (c. 1982 -1991).

GT, Ford Motor Company, 2017

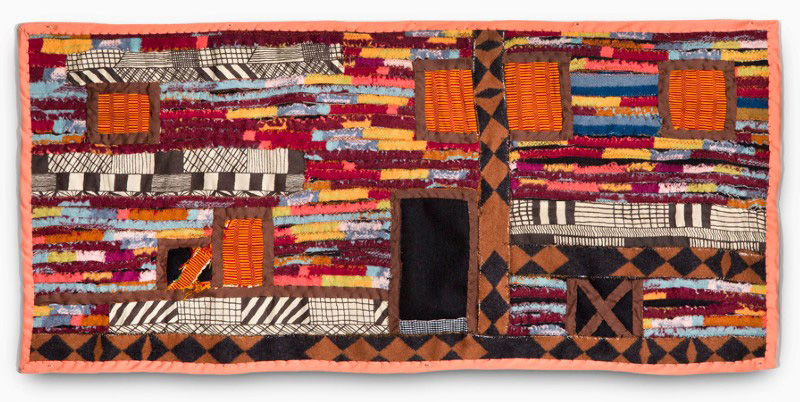

Kristin Baker, The Unfair Advantage, acrylic on PVC on board, 2003

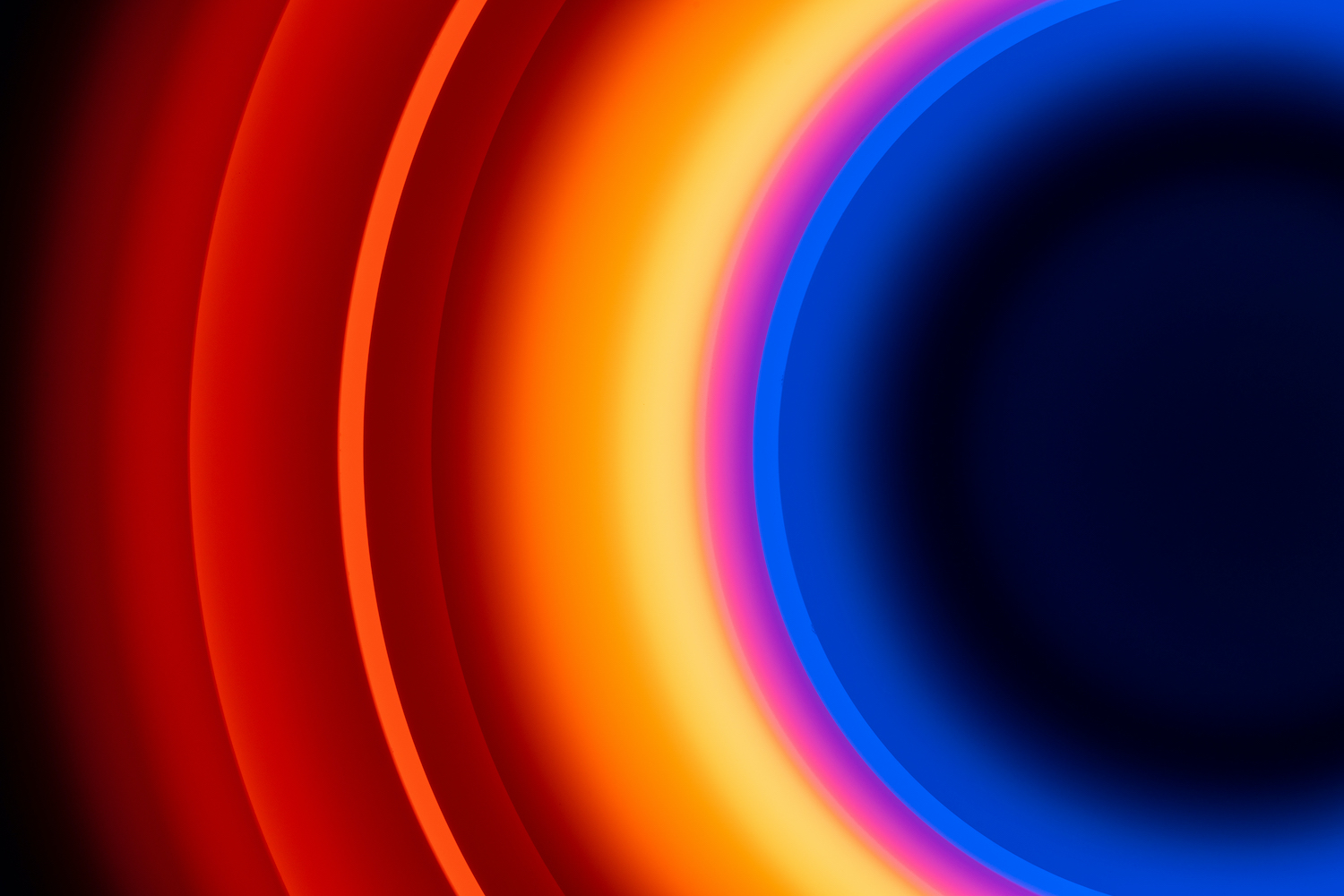

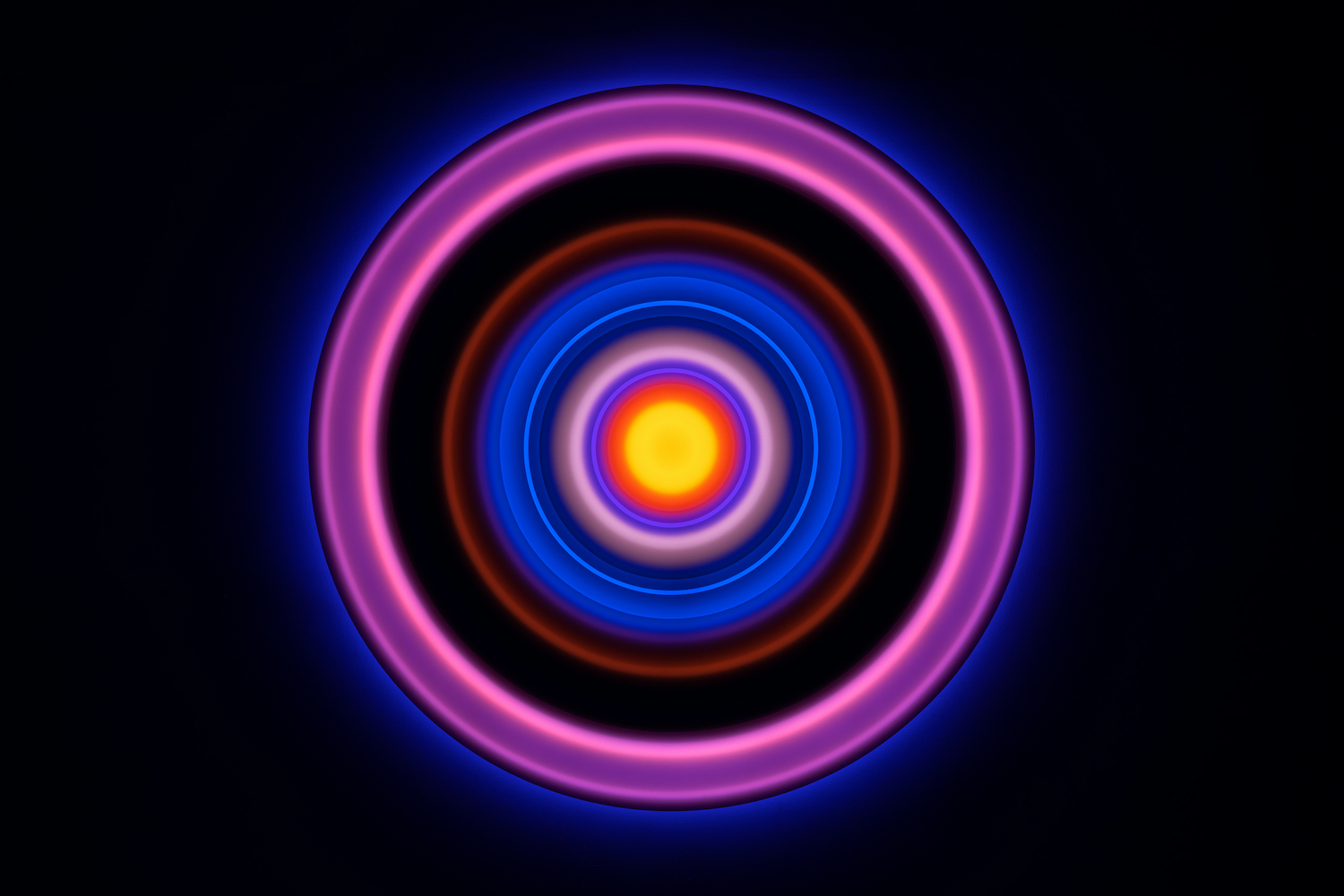

The final gallery, sparely installed, is home to just two works: an electric blue, sinuous, teardrop shaped GT (Ford, 2017) and Kristin Baker’s large scale, mixed media composition The Unfair Advantage (2003). The swept-back lines of the low-slung GT, a reinterpretation of a racing car legend of 1966, telegraph power, speed, machismo. Baker, alternatively, presents a cautionary work, an updated Futurist scene (landscape, raceway?) that evokes jagged, colorful forms whizzing by AND, as a counterpoint, the blurred, roiling smoke and fire indicative of a catastrophic crash. Nothing like ending the show with a bang!

Videos, accessible here, provide perspective on how Detroit’s iconic vehicles are created with this interview series featuring car designers Ralph Gilles, Emeline King, Craig Metros, and Ed Welburn. The four designers share their insights on favorite cars, the use of materials, and the collaboration between designers and engineers.

“Detroit Style: Car Design in the Motor City, 1950 – 2020” is on display at the DIA through June 27, 2021. Keep in mind that to view the exhibition you will need to reserve in advance a specific day and time for your visit.