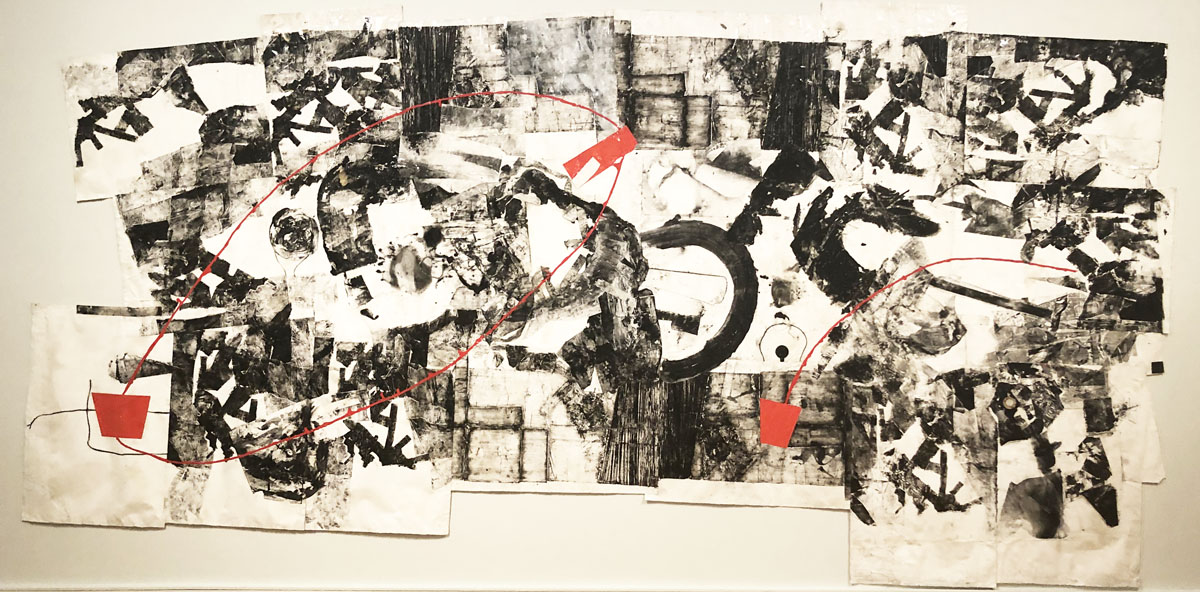

Install Image, Alternative Testimony, Image Courtesy of David Klein Gallery

Alternative Testimony, a group show at David Klein Gallery that is part chemistry experiment, part art historical tour of photographic processes, features the work of four artists who have slipped the tether binding conventional photography to representation. They proceed to spin the medium off into new and unexplored territory where the resulting abstract images challenge established notions about the function and purpose of photography.

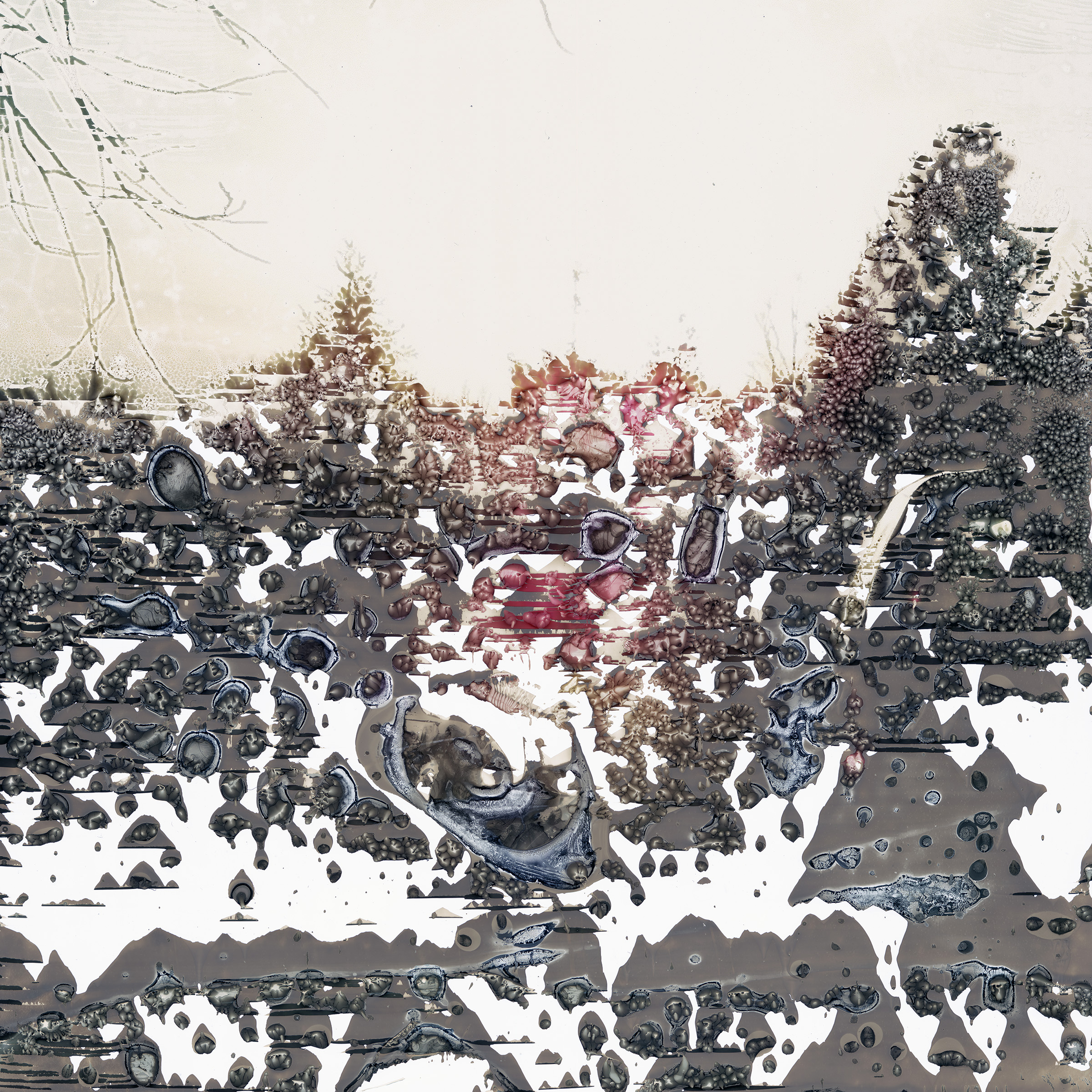

Untitled: 3/23/2016, 8:15 a.m., by Cyrus Karimipour, archival pigment print, 44” x 44” (ed.1/5, 2 ap) All photos are courtesy of David Klein Gallery

Cyrus Karimipour’s hazy pastel vistas are barely-there evocations of images recorded by trail cameras. He placed them on his remote Michigan property, where they documented trespassers over the course of several years. At first, he viewed the hikers as unwelcome interlopers, but Karimipour came to accept them as a part of the natural wildlife on his land and as a resource for his work. “I used to dread finding people on the cameras, but now I rely on their presence,“ he says.

Karimipour combines contact printing, a photographic technique popular in the 1890’s, with contemporary inkjet materials to create a kind of process art. His method depends on the serendipitous interaction of built-up pigment on low adhesion film, which is then applied to a more absorptive surface. The pigment immediately dries and bonds the films to each other. The effect, which is evident in Untitled, 03/23/2016, 8:15 a.m. is somewhat map-adjacent, like traditional Asian charts that render the view in forced perspective from a high, almost aerial, angle. Much of the visual incident in each picture comes from the bubble-like spherical puddles distributed throughout the composition. The ghostly result is a little reminiscent of video static, through which, occasionally, one can detect trees, humans and the like, purely coincidental remnants of the artist’s time-based exploration of the landscape.

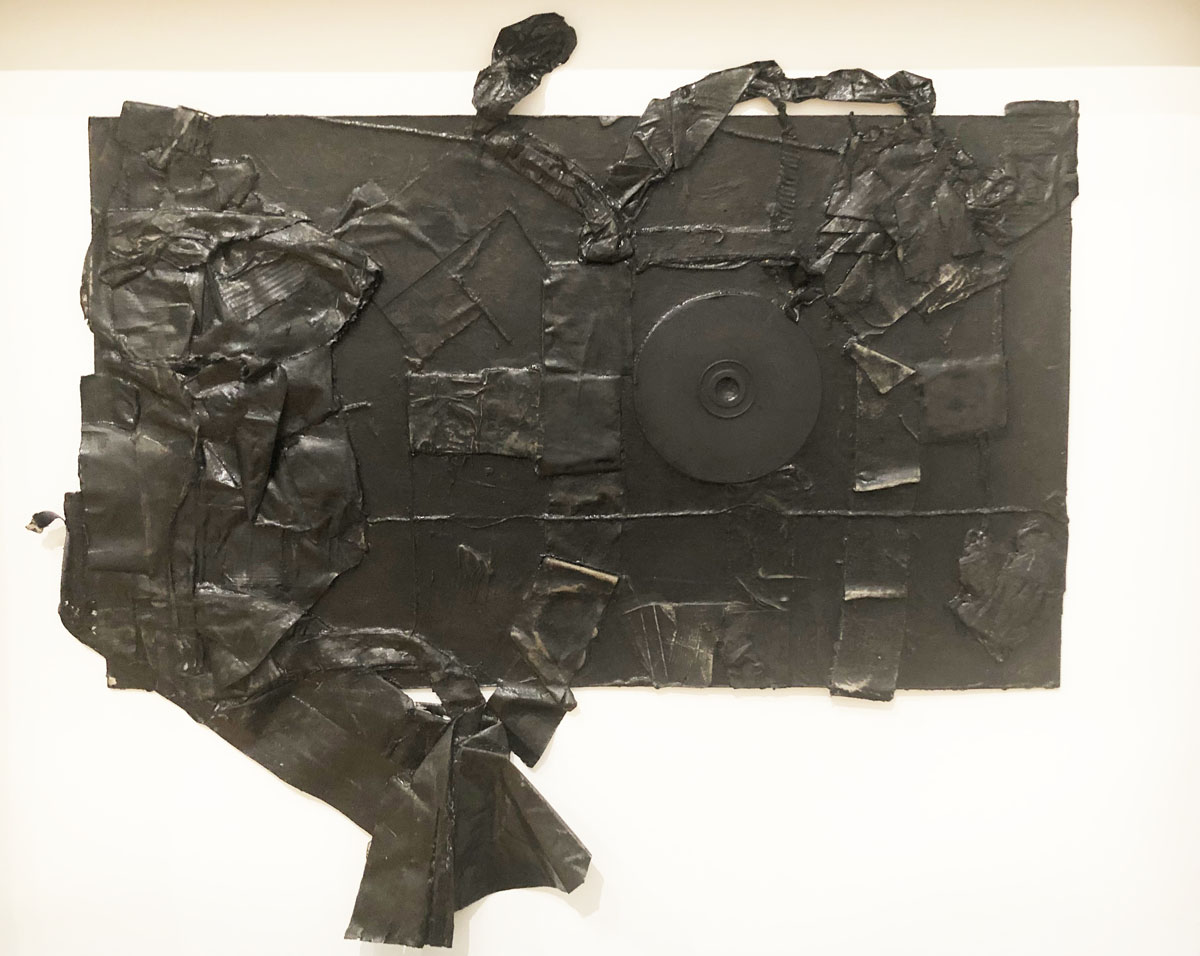

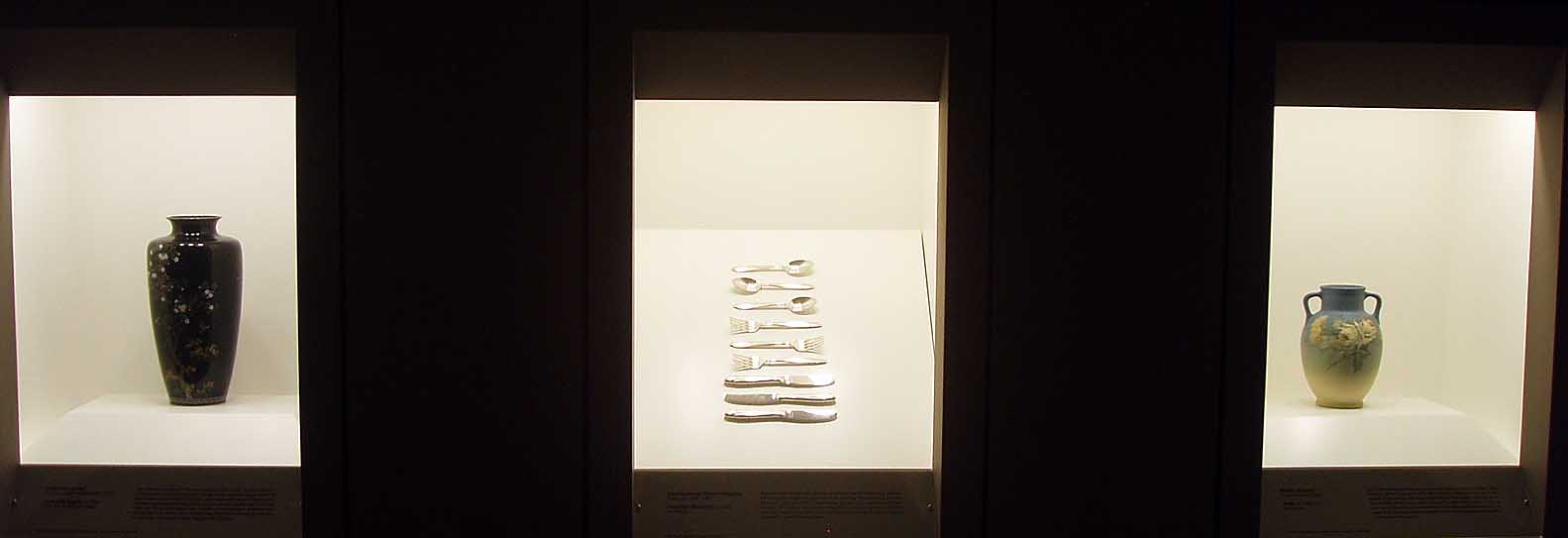

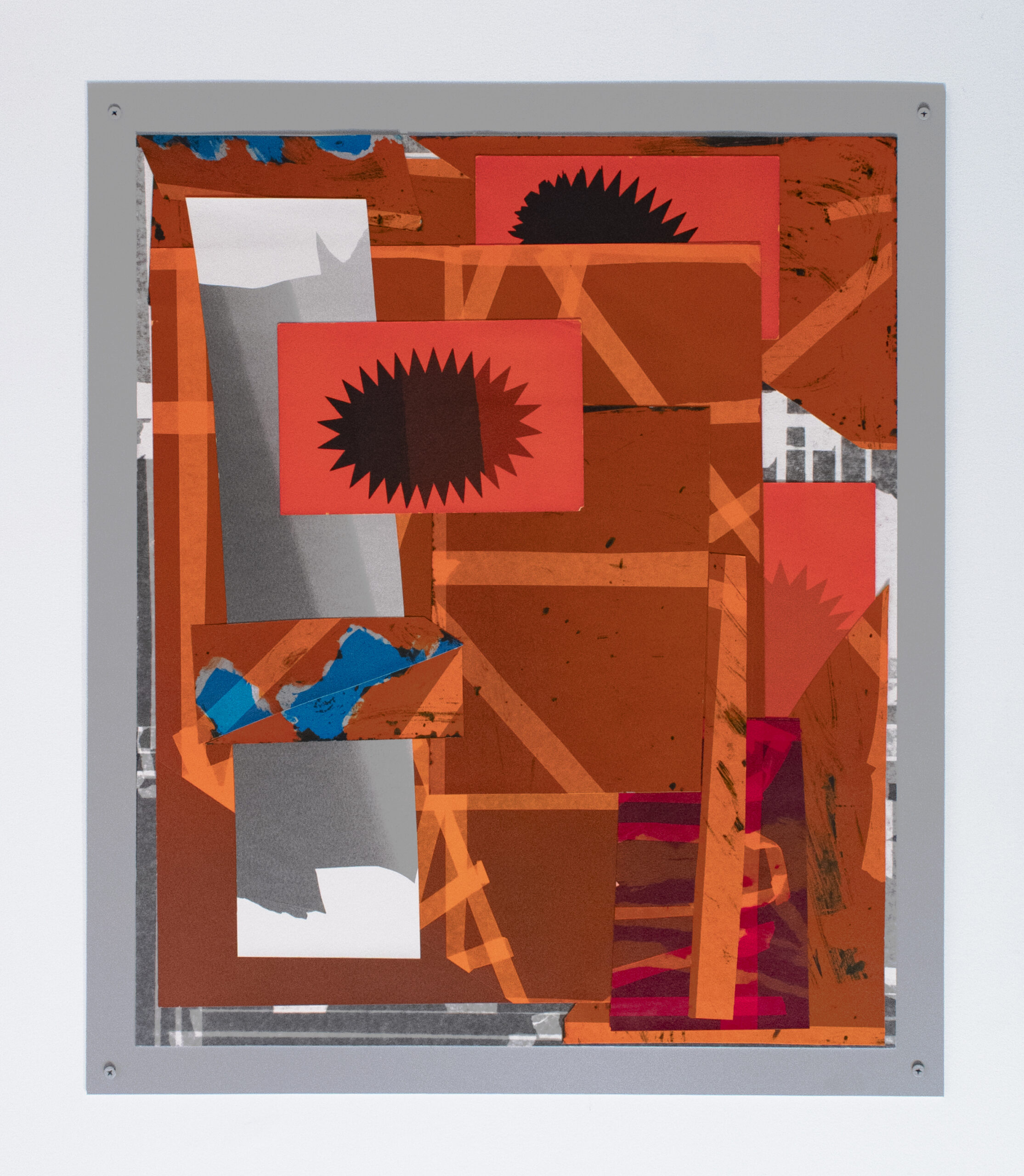

On the opposite gallery wall from Karimipour, dimensional collages by Aspen Mays document her long and complicated relationship with the weather–specifically, her recollections of Hurricane Hugo. The category 4 storm devastated her hometown of Charleston SC in 1989 and provided the inspiration for her Hugo Series. Many of the elements in these assemblages recall her youthful memories of the storm, although the artist freely admits they may be genuine recollections or merely media images that have infiltrated her reminiscence. She recalls with particular interest the ritualistic taping of windows in preparation for the storm, an activity that she describes as more shamanistic than practical.

Hugo 23, by Aspen Mays, 2019, gelatin silverprint, photo gram, blue sintra, 26.5” x 22.5”, unique

Hugo 20, by Aspen Mays, 2019, gelatin silverprint, photogram, grey sintra, 26.5” x 22.5”, unique

In the artworks themselves, grids and x-es of masking tape, starburst shapes and free-form fragments generate exuberant architectonic compositions. The layered gelatin prints of photograms on rag paper, cut up and reassembled on colorful sintra backing, are curiously cheerful and appealingly tactile. Mays describes the colors as derived from the alert codes used on weather maps to indicate violent weather patterns, but her palette projects a child-like optimism at odds with apprehensions of disaster.

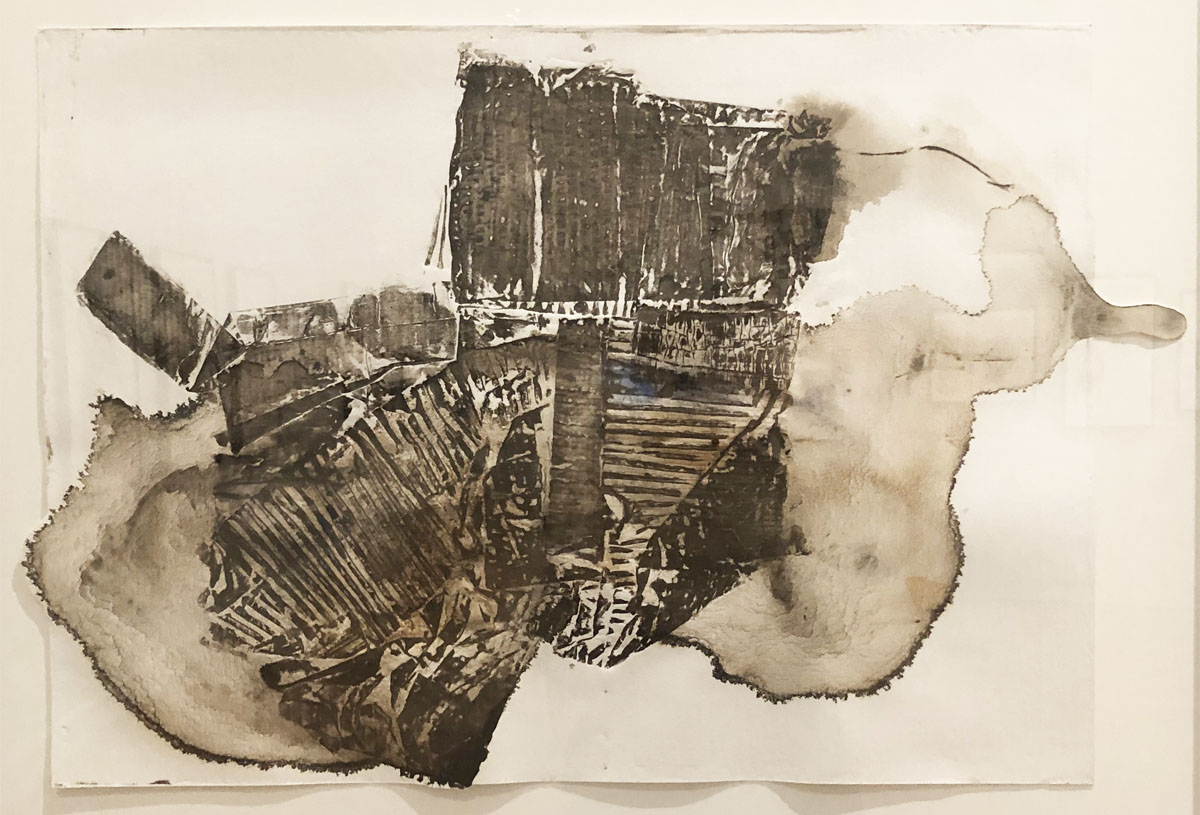

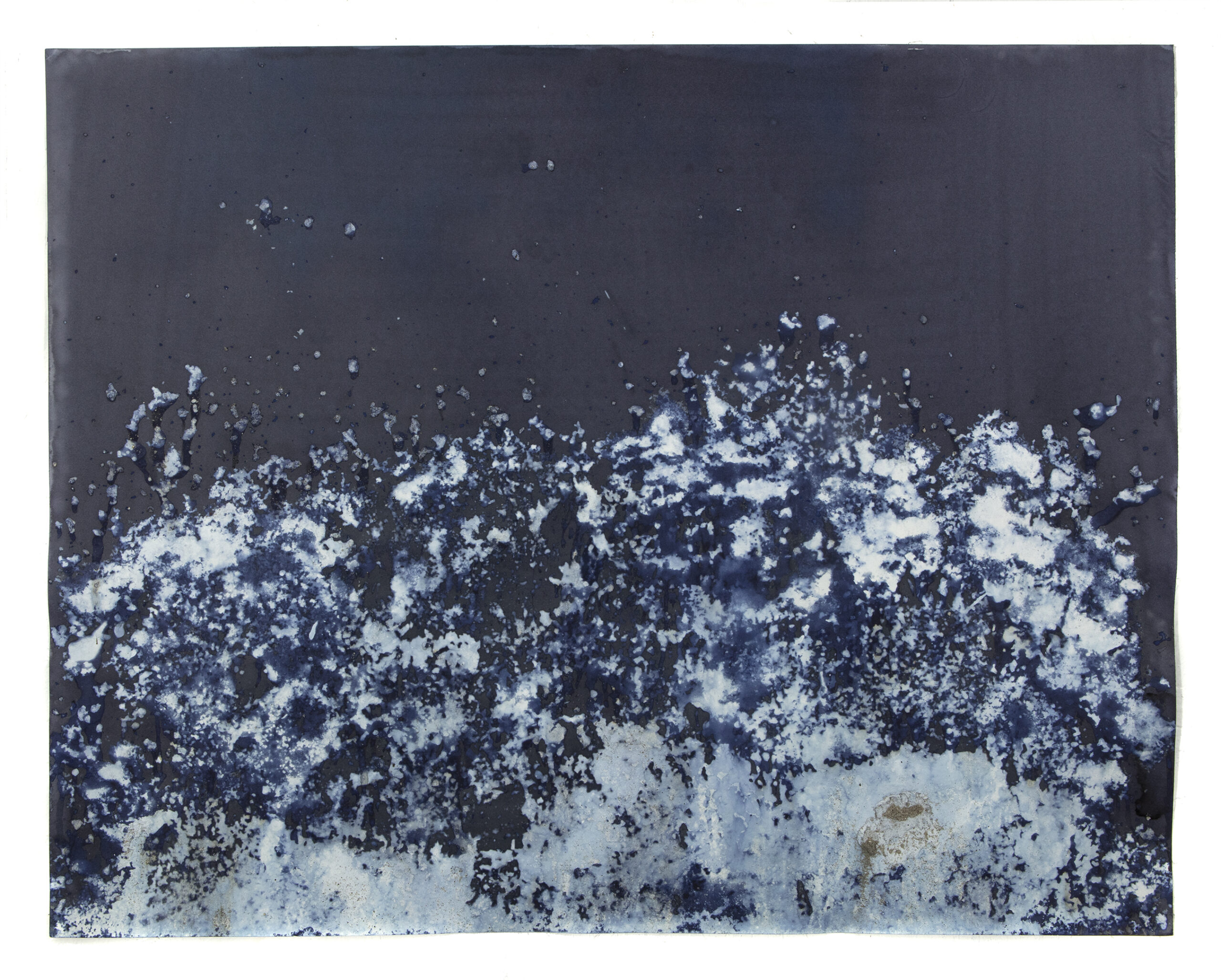

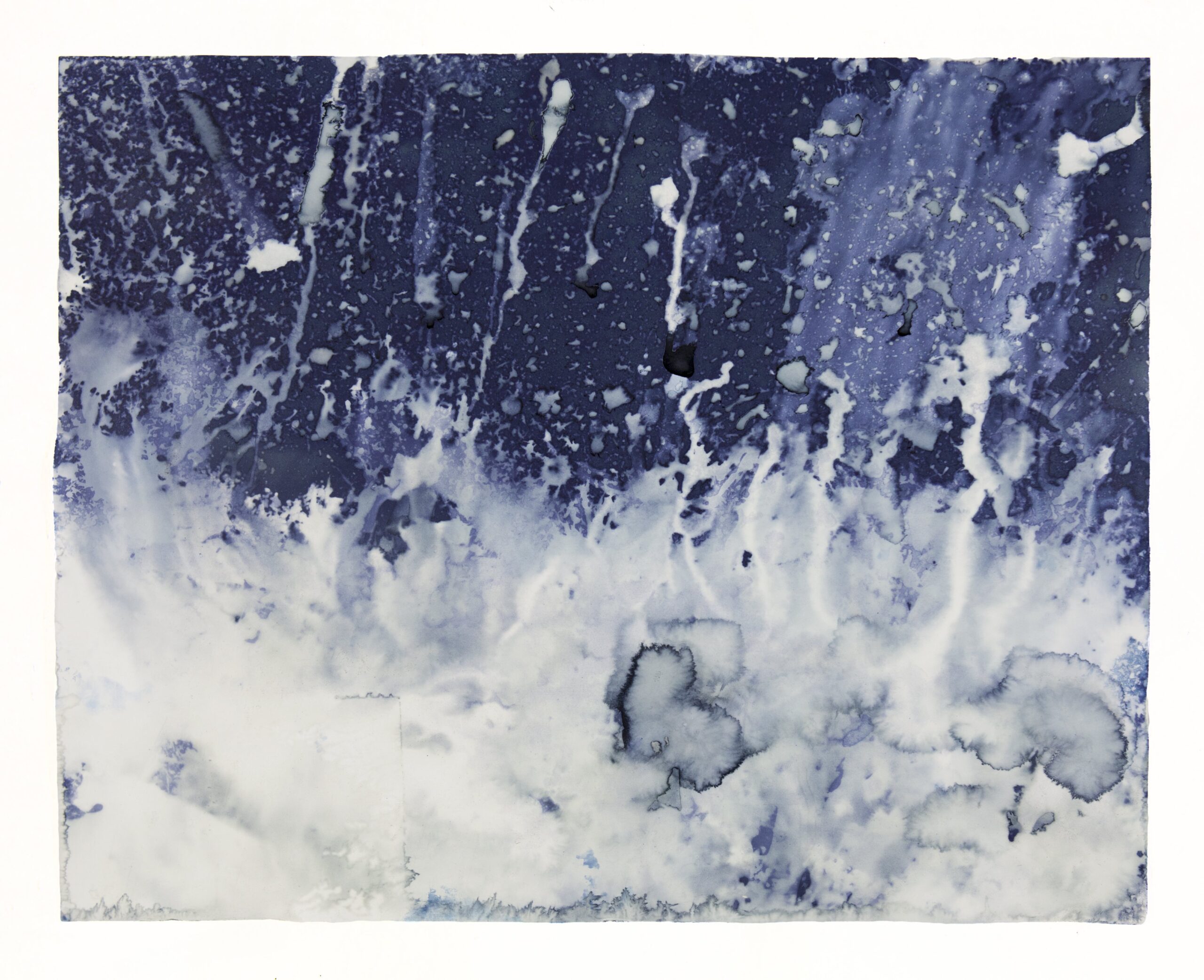

With her cyanotype prints, west coast-based photographer Meghann Riepenhoff engages directly with the natural environment and, in particular, with the dynamic temporal features of her watery surroundings– rain, snow and ice, wind and waves. Cyanotype, a photographic process that will be familiar to many from childhood craft projects, is the fairly primitive technique that the artist employs to brilliant effect in her program to directly record fugitive natural phenomena. She says, “Each cyanotype is like a fingerprint of a place, a hyper-literal, sometimes three-dimensional photographic record of specific cumulative circumstances.” Her cyanotype Ecotone #163 exemplifies the specificity of her vision: it is a physical record of snow, rain and melting ice on a draped construction barrier in front of a New York City gallery. The rich shades of blue in these visual records of natural phenomena develop over 48 hours and continue to respond over time to local conditions.

Ecotone #163 (parking space in front of Yossi Milo Gallery, New York City, 3/14/17, snow rain, melting ice draped on construction barrier), by Meghann Riepenhoff, dynamic cyanotype, 19” x 24”, unique

Ecotone #287 (Pier 4 beach, Brooklyn, New York, 12/17/17, melting snow under shelf ice), by Meghann Riepenhoff, dynamic cyanotype, 19” x 24”, unique

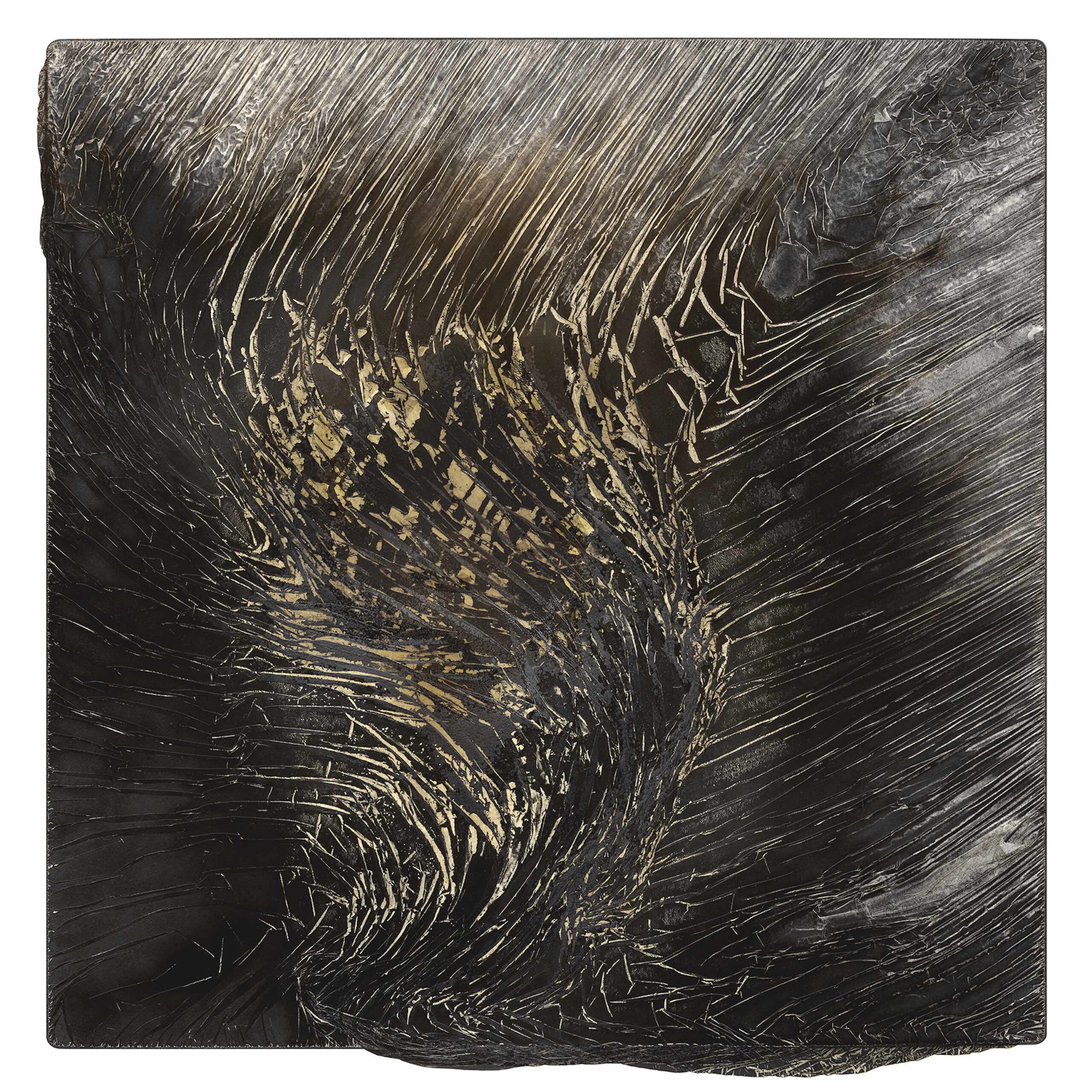

Of the four artists in Alternative Testimony, Brittany Nelson seems to be the most militantly committed to discarding photography’s traditional preoccupation with the surface appearance of things and places. Instead, she engages in an experimental exploration of the medium’s chemical essence.

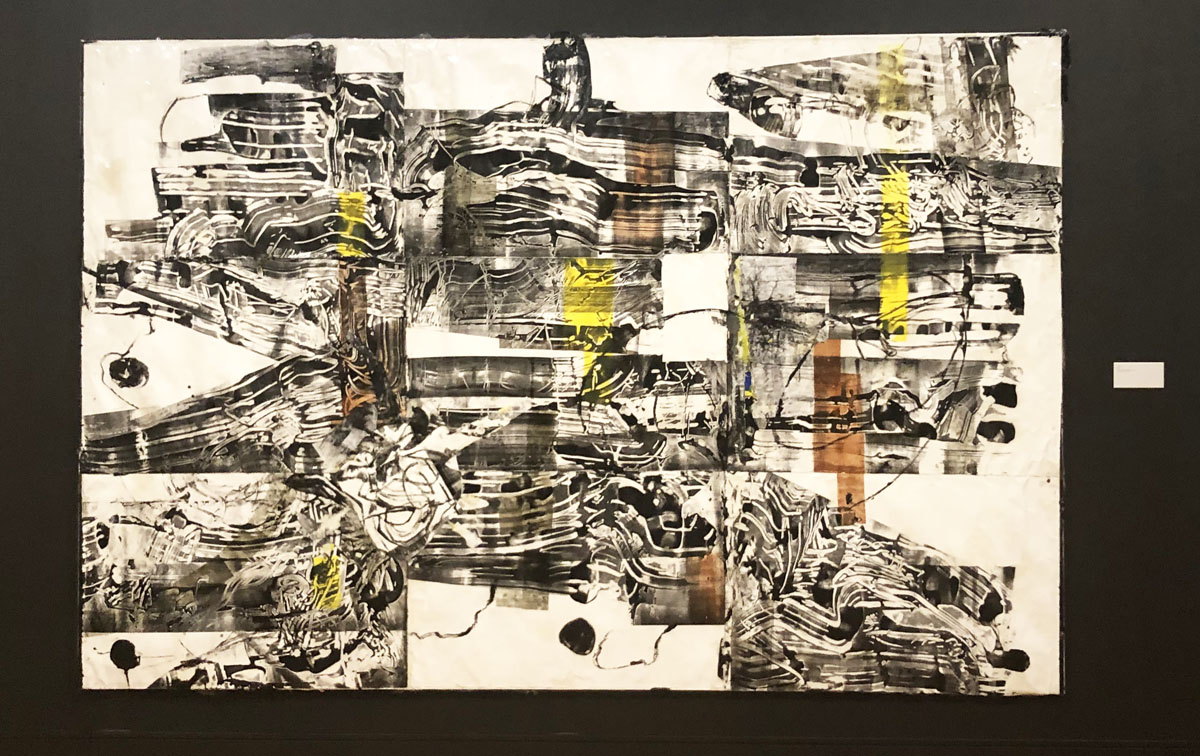

The two (very large) works by Nelson in Alternative Testimony depend for their visual charge on arcane and caustic 19th century processes. Mordencage 5 employs a hybrid procedure that starts with the eponymous mordencage, a translucent veiling, draping effect caused by the chemical reaction of acid with the silver content of gelatin paper. The resulting (very small) print has been digitally enlarged to highlight the diaphanous striations.

Mordencage 5 – 2020, by Brittany Nelson, c-print, 72” x 72”, (ed.1, 2 ap)

It is a little ironic that the only image in Alternative Testimony that can be described as a standard landscape has been produced by Nelson, who most categorically denies the relevance of the pictorial in contemporary photography. The scene, though, is hardly mundane–in fact it is other-worldly in the most literal sense–a 4 ft. x 6 ft. bromoil print of a Martian landscape from the NASA archives, the largest of its kind ever produced. (bromoil, popular in the early 20th century, is created when a silver gelatin print is bleached and then soaked in water and coated with oil-based ink.)

Tracks 2 – 2019, by Brittany Nelson, bromoil print, 48” x 72”, unique

Each of the four artists in Alternative Testimony can claim a unique art practice, but what they share is unfettered curiosity and a willingness to experiment with alternative photographic processes in unique ways—in combination with contemporary tools— to achieve their formal goals. By avoiding the merely representational, they have found a new and deeper reality at the intersection of science and art, observation and expression.