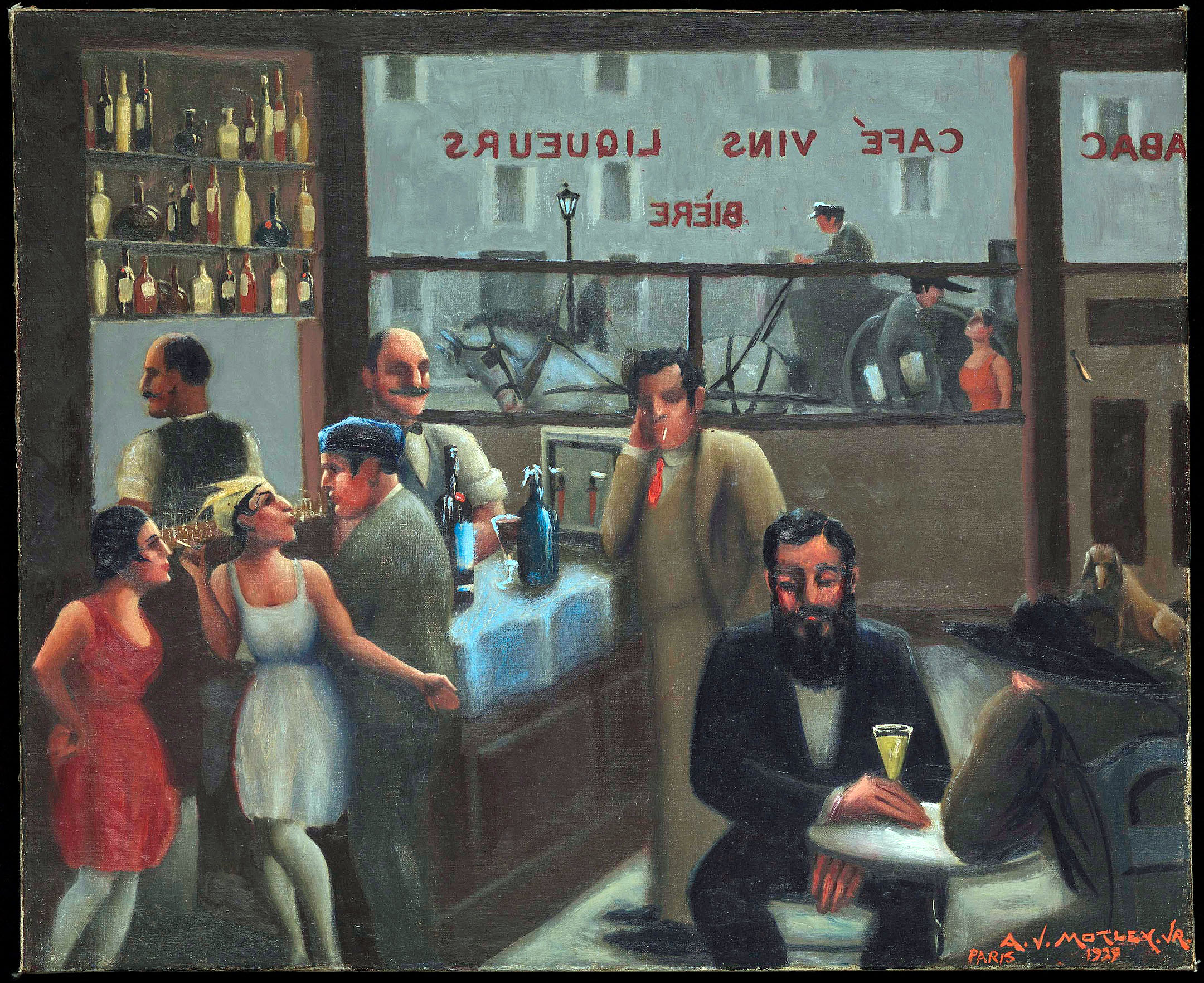

An installation shot of Marianna Olague: People You Know at Detroit’s David Klein Gallery, up through Dec. 23. Running simultaneously: Patrick Ethen: Selected Light Works. (All photos courtesy David Klein Gallery)

Need to get out of the cold? Two shows blazing with light and color in downtown Detroit at the David Klein Gallery should help warm you up and capture your attention at the same time – Marianna Olague: People You Know, and the electronic Patrick Ethen: Selected Light Works. Both shows are up through Dec. 23.

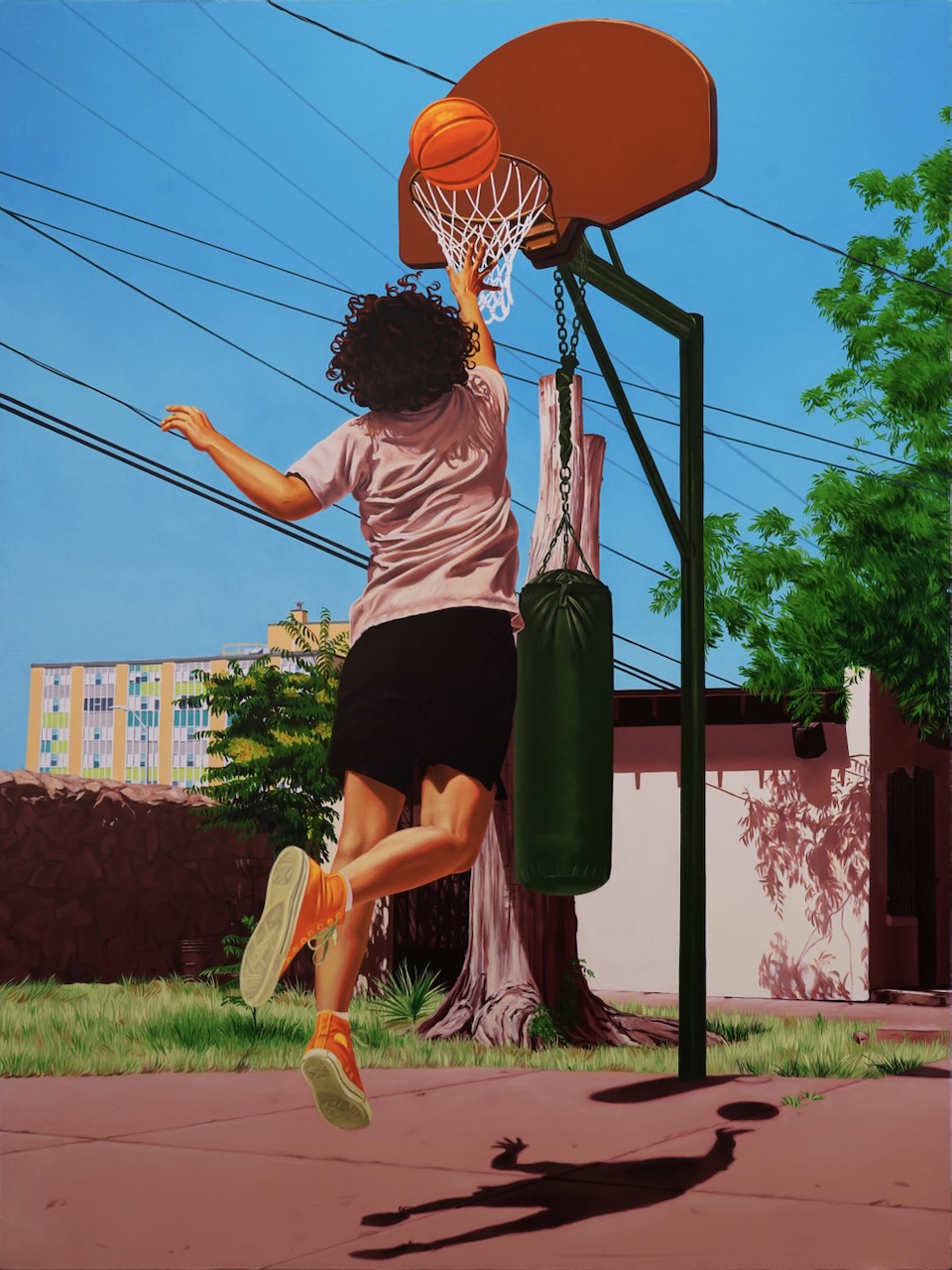

People You Know is the latest in a series of deeply convincing portraits that Olague has produced of family and friends in her hometown of El Paso, Texas, where she’s based. Olague’s gifted on many levels – her technical mastery is striking – but perhaps rarest of all is her enviable skill at finding and replicating the astonishing beauty of the mundane.

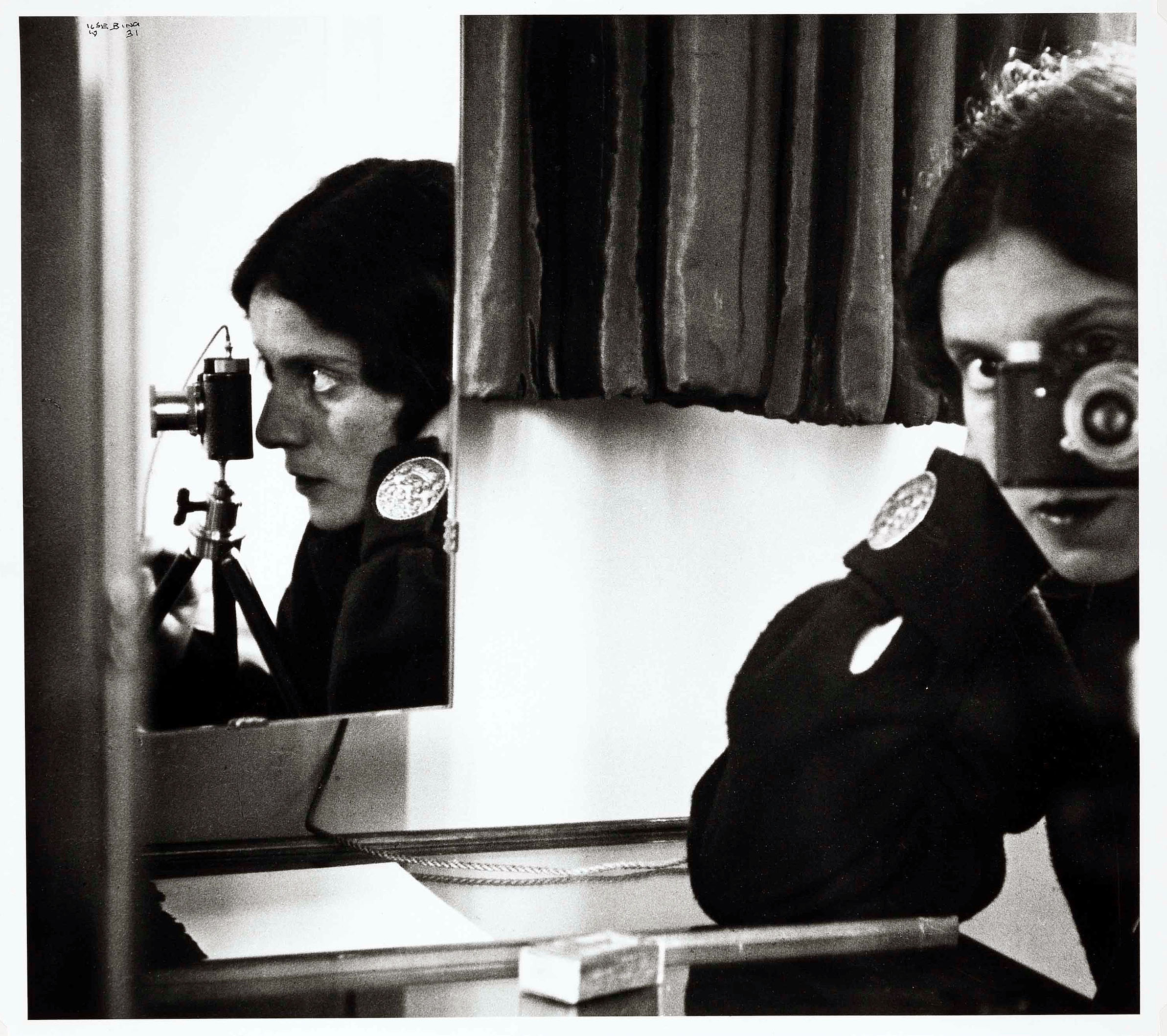

Marianna Olague, A Home of Our Own, Oil on canvas, 60 x 58 inches, 2023.

Olague, who got her MFA in painting at Cranbrook in 2019 and a drawing degree at the University of Texas at El Paso, where she now teaches, creates transfixing portraits rendered in a palette she calls “over-saturated and improbable.” Or call it an intensified version of the way life looks under the pounding Rio Grande sun. In A Home of Our Own, Olague plays with a range of orange hues, from the saffron on the concrete blocks to the tanned skin of the young man whom Olague catches in an unguarded moment, gaze locked on his beloved. There’s a luminosity to A Home of Our Own, visible not just in the impossibly warm orange of that concrete wall, but in the trust and mutual dependence that radiate off the handsome young couple.

While the U.S.-Mexican border itself isn’t represented in these compositions, “it remains,” as Olague writes in her artist’s statement, “an omnipotent presence both on and off the canvas.” Case in point: she notes that the young couple in A Home of Our Own commute back and forth daily between El Paso and Juarez, Mexico.

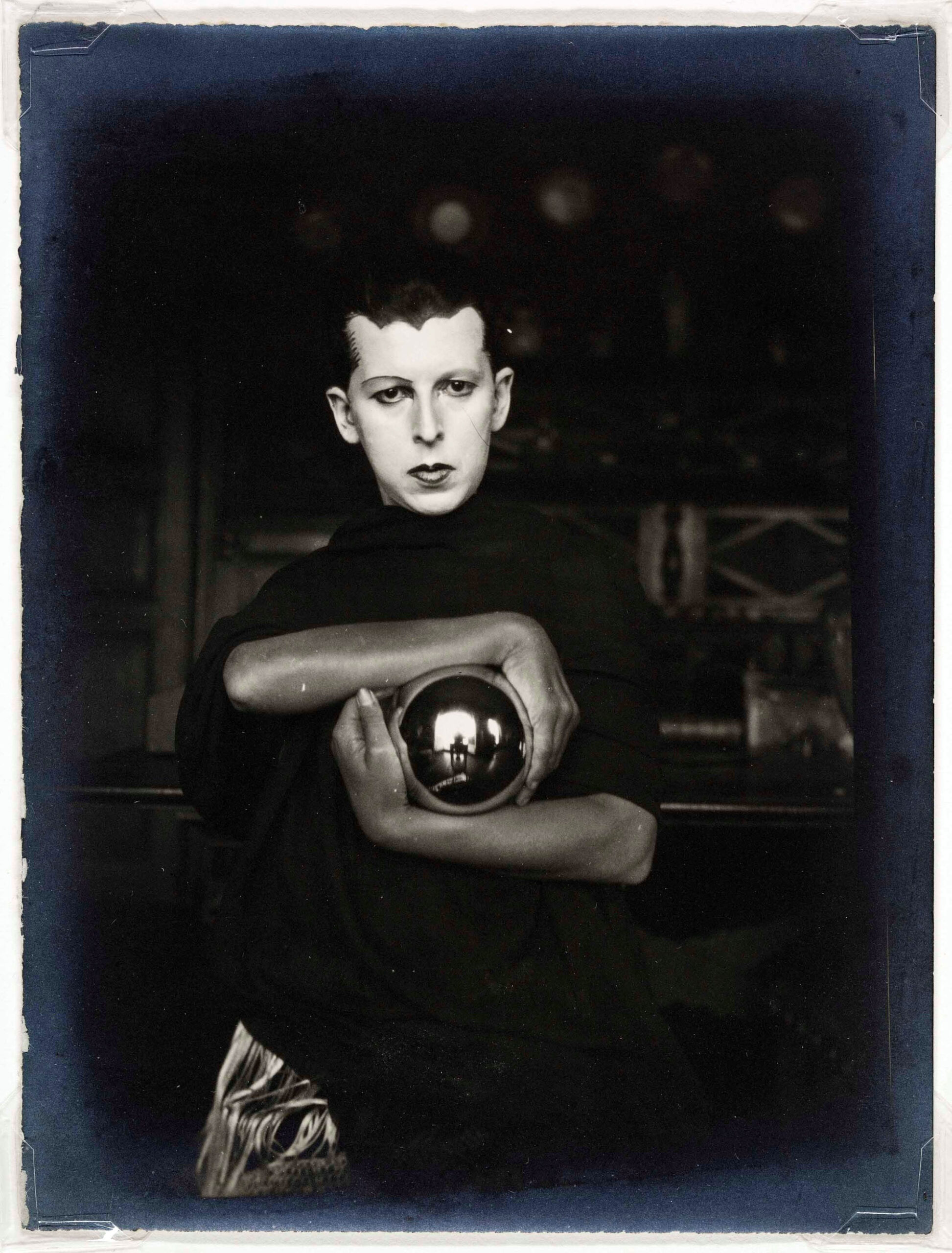

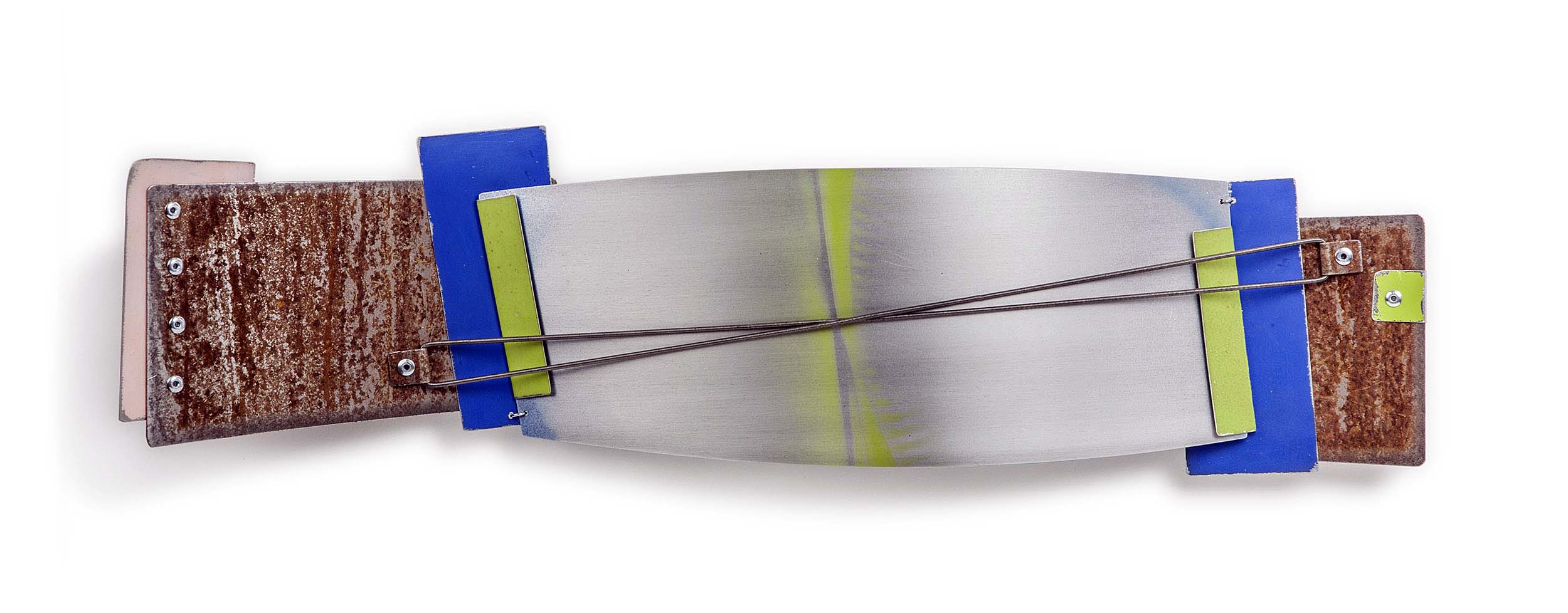

Marianna Olague, H.O.R.S.E., Oil on canvas, 64 x 48 inches, 2023

Most of the eight portraits here are static, the subject usually seated, generally looking at the viewer. Only H.O.R.S.E. packs kinetic energy, and in this case, the shadow’s the thing – floating beneath the soaring athlete caught mid-leap on the basketball court. Not only does the shadow itself, almost comic in its simplicity, suggest movement, but it gives us a different perspective on the young person in motion – almost like a camera shot from another angle – that makes the whole composition suddenly feel rather 3-D.

Strong colors organize H.O.R.S.E. as much as with A Home of Our Own, but the centerpiece of the portrait – the youngster, seen from behind, jumping and aiming for the hoop – is rendered in muted tones against dull concrete. Balancing those are the piercing green of a tree arched over a storefront, the powerful blue sky, and the orange glow of both basketball and the player’s high-top sneakers.

By contrast, the show-stopper “Onyx” is a dazzling color study in deep blues and yellows starring a sweet-looking black dog seated in front of a kitchen table and chairs, all of which Olague’s simplified until outlines dissolve into blocks of strong color. Shadows in a range of electric blues dominate the frame, scissored here and there by linear strips of sharp sunlight crossing the floor. As color studies go, it’s a knock-out, and does pretty well in the why-we-like-dogs department, too.

Marianna Olague, Onyx, Oil on canvas, 56 x 40 inches, 2023

“Quickening” is a tribute to the artist’s sister, who was eight months pregnant at the time of the painting. Seated on a deck outdoors in late sunset light, Olague’s framed the young woman’s forthright, determined face with a long, pink robe beneath and mottled tones of blue and green forest above and beyond. There’s an engaging verticality at work – in the upright, yellow slats of the railing behind the young woman, and the shadows from their mates on the opposite side that land, distorted into curves, on the woman’s waist and hips.

Marianna Olague, Quickening, 72 x 50 inches, 2023.

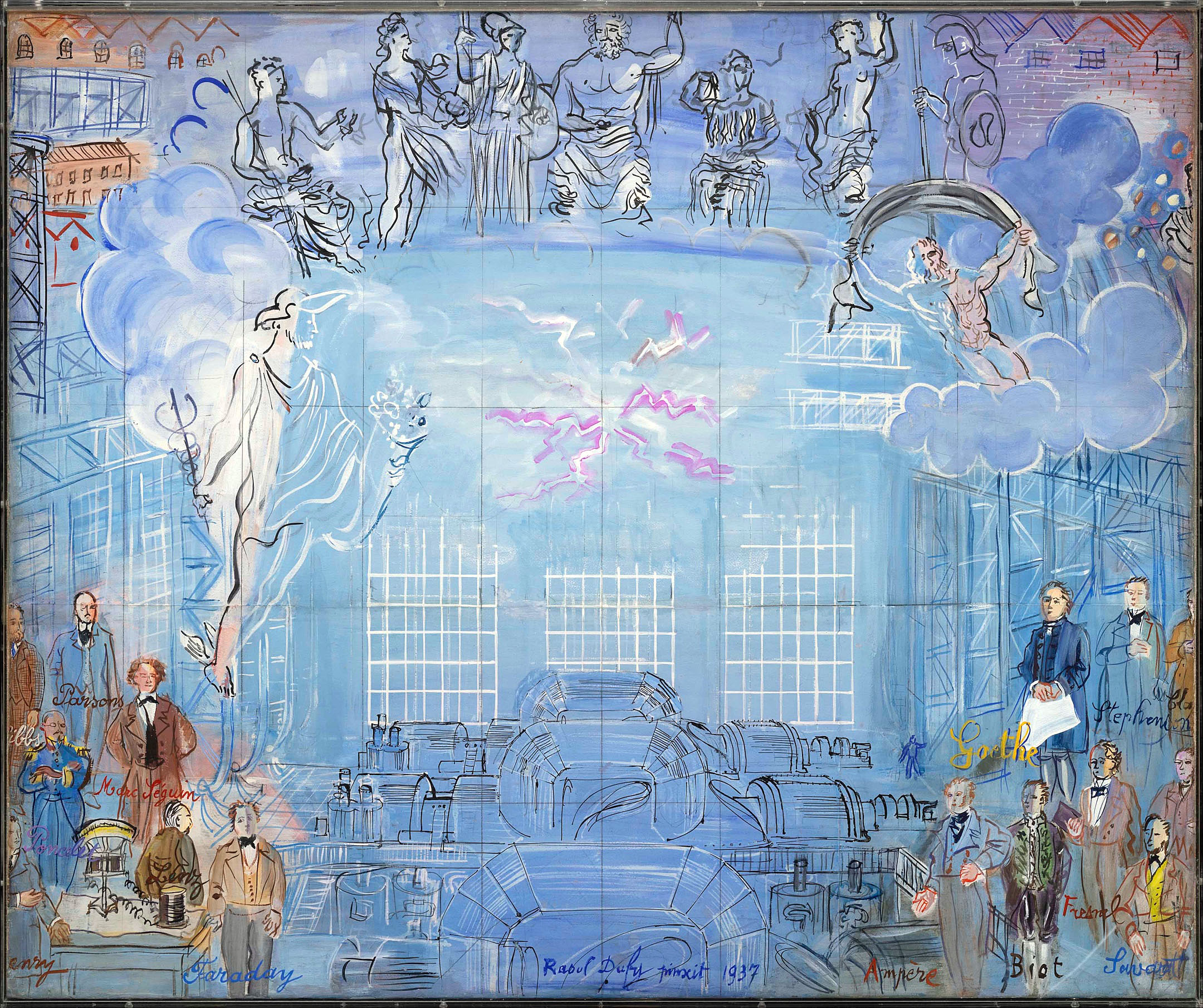

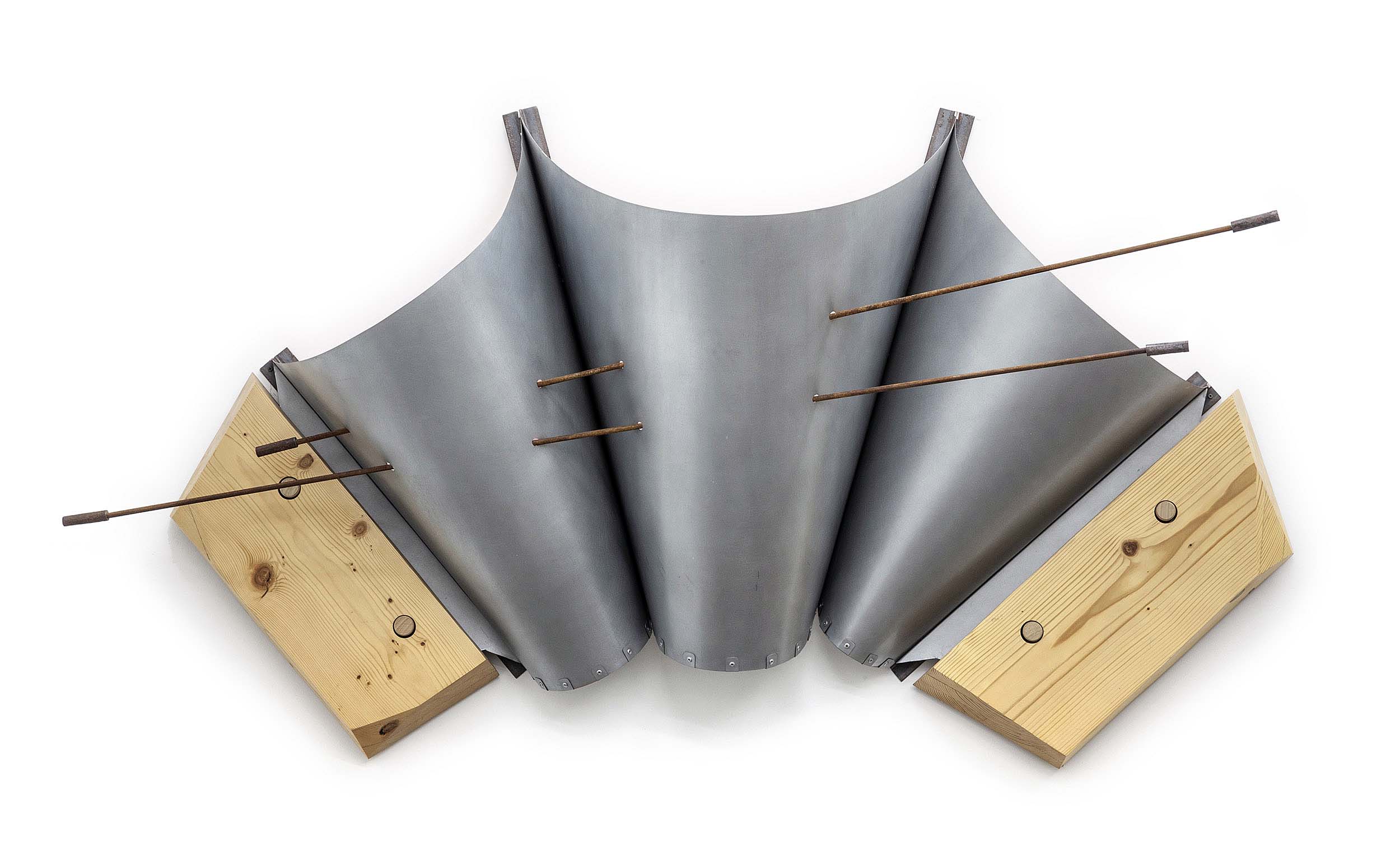

In the gallery at the back of David Klein, don’t miss the small solo show – Patrick Ethen: Selected Light Works. Ethen’s light designs are a treat, and have been featured in Detroit’s iconic Movement Electronic Music Festival, Murals at the Market, as well as Detroit Design Week. The works on display here are all small light objects that could go on a household wall, but some of his outdoor installations can be large and immersive. Exploiting both digital and analog technology, Ethen, who’s an architecturally trained artist and designer, gives his practice a New Age spin by calling it a sort of “pseudo-spiritual techno-futurism.” His process of assembling his constructions has been likened to weaving, albeit with circuitry and electronics.

Patrick Ethen, Valence Shell, Sculptural light installation, 19 ¾ x 19 ¾ x 4 ¾ inches, 2023.

Marianna Olague: People You Know and Patrick Ethen: Selected Light Works will both be up at Detroit’s David Klein Gallery through December 2o23.