Family Album: Faina Markovna Lerman at Cave

Faina Markovna Lerman worked with photographs to make the twelve paintings that comprise “Family Album” currently exhibited at Cave in the Russell Industrial Center. The photographs are mostly stored in the family album from which she took the name and from which she worked. In her artist’s statement for the exhibit she says:

“These paintings are inspired by the desire to honor my family history and experiences that are fading, gone, or were well before my time. They reference photos from the 1950’s (post WWll Latvia)-1980 (when my family immigrated to the United States)”.

To make paintings in honor of the family is to celebrate and remember its existence but Lerman uses photos which, typically, already serve as memories. Family photos are the evidence, the signs, that the family was, and provide a sense of continuity and context, even likeness for heirs to compare themselves, to find lineage. As artifacts, they carry with them their own cultural information: the serrated edges of the square format photos, the fading chemicals used to make them, and the eroding paper on which the images are printed, these things locate them in time. What Lerman is after is more complex than either the fact and corroboration of their existence.

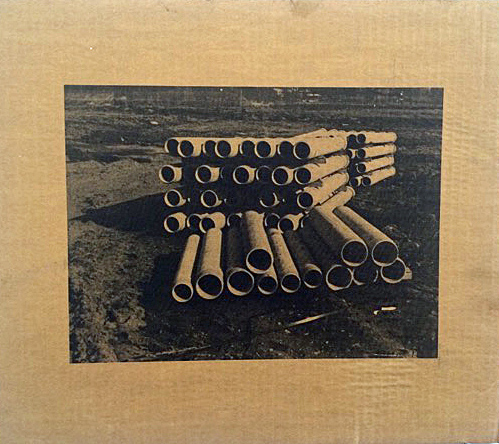

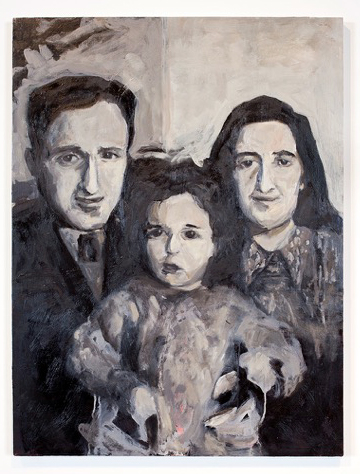

Faina Markovna Lerman, “Baba, Dzeda and Mom before Josef arrived (Riga 1955)” Water-based oil on wood, 2017 All images courtesy of Corine Vermeulen

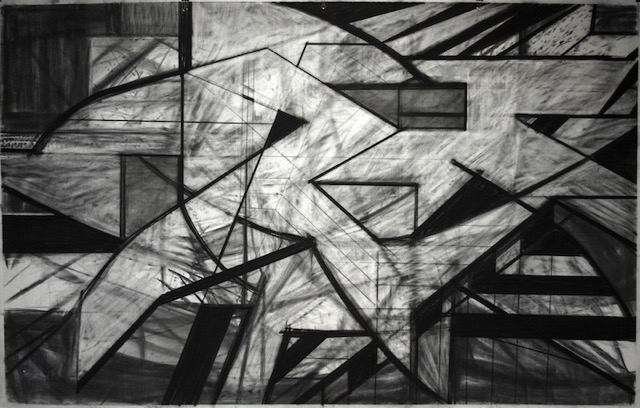

The first image that we encounter, and there is a definitive evolution of the twelve paintings, is “Baba, Dzeda and Mom before Joseph arrived (Riga 1955).” It is a black and white painting with pink tinges shadowing the figures. (I learned that Lerman painted over a painting of her grandfather with which she was completely dissatisfied: “There was red in it.”) We get a sense of her pursuit by the title. Baba and Dzeda are Russian names commonly used for Grandmother and Grandfather, and it is clear in this painting that Lerman was after likeness to the photo and mirroring the initial effect of the image at which she is gazing. She is interrogating the photo searching for connection. Whether intended or factual or not each figure has the same brush- stroked nose to accomplish the notion of family. Wonderfully the act painting contains a genetic component. Most interestingly Dzeda’s half of the portrait is shaded darker than Baba’s and her mother (Lerman’s mother), the baby between them, is half shaded and half in the light, representing a genetic sharing of her parents. Is this a conscious mirroring of the photograph or is it a factor of Lerman’s desire to find likeness in her family? While classically sober, in keeping with traditional family portraits, it is an energetically expressionistic rendering of her mother and grandparents. Each brush stroke is deft and fraught with meaning. The figures express an innocently touching but uncertain humanity.

Photographs might be considered a pure, distilled concentrate, a moment composed of many recognizable signifying features, a face, a nose, a certain dress, of a life. In her paintings Lerman is working at reconstituting a family “fading, gone, or were well before my time.” The painting becomes the echo within her of first family, of ontologically, her beginning. The painting is a reification of that history. It is not a slavish copying, but a deep mining of herself to affirm their lives.

Latvia, along with Lithuania and Estonia, borders the Eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Riga, the capital of Latvia, where the photo was taken, was torn, like all Baltic Soviets, between Germany and Russia, between persecution of the Jews by both the invading Nazis and by Latvian nationalists themselves, and by the Russians. That said, Latvia was where Lerman was born and the site of her early childhood. “That culture, that landscape, the food, the smells, the music, that world is disappearing, that moment of the world is maybe gone and I want to preserve it somehow. I want my children to know it. When we would have dinner before they were gone I would sit there eating and cry, cry while I was eating, knowing how fragile the moment was and that it was disappearing.”

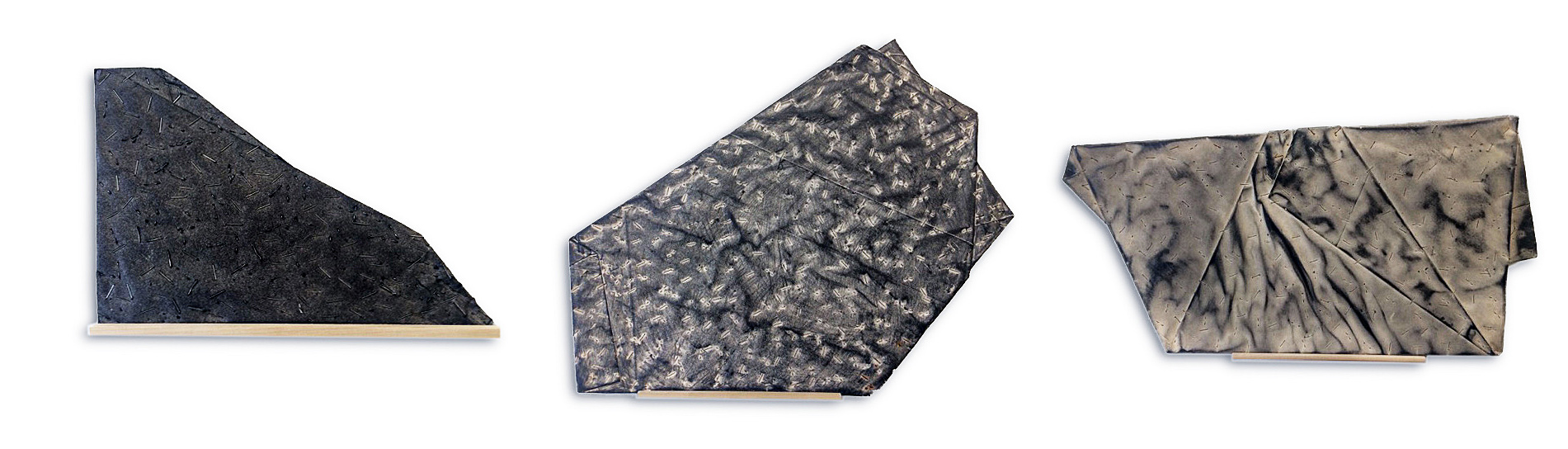

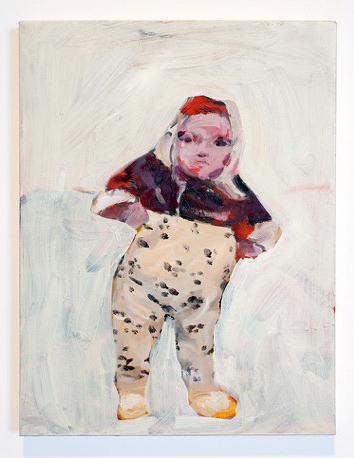

Faina Markovna Lerman “The Baby with a fever (Riga 1976)”, 1Water-based oil on canvas, 2017

There are two other paintings from Riga. One is “The Baby with Fever (Riga 1976)” based upon a photo of Lerman as an infant, straddled and supported by her parents. Her mother told her that because she was sick with fever she had bundled-her- up against the cold. Lerman painted-out, or intentionally left her parents out, and added color to the black and white image as if to create a reality for herself as a child that has faded or that she never had. It is a loose, gestural painting, with the sense of the infant almost rescued out of the painted-out background. There is also a look of decisive and emerging identity in the painting of the infant that Lerman has asserted.

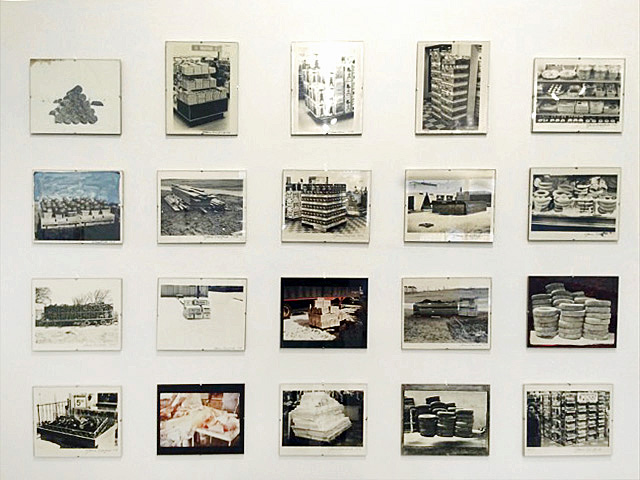

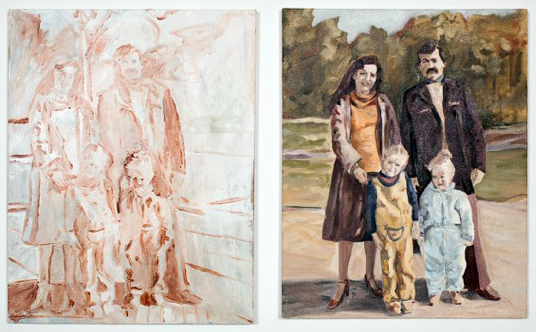

Faina Markovna Lerman, “Rainis Park (Last family photo taken before coming toAmerica,1980),” Water-based oil on canvas, 2017

The other painting, “Rainis Park (Last family photo taken before coming to America,1980),” is a diptych. One panel is an almost transparent, study-like sketch of Lerman’s immediate family, her mother, father, sister and her. Riga’s Rainis Park is infamous in history as a site where in June 1941 the Nazis gathered and shot 300 Latvian Jews, and thousands of other Russian patriots and Jews were murdered in and around Riga. The transparent quality of the study, juxtaposed to the second painting that reveals a stylish and life-affirming family, throws a painful question into Lerman’s narrative tableau of what could have been.

Faina Markovna Lerman, “Baba Sonya and Josef with horses (date and place unknown),” Water-based oil on canvas, 2017

There is a strong sense of evolution in “Family Album.” The paintings become looser and gestural, almost abstract. She is comfortable with her gestures and the marks she makes on the canvas are convincing and beautifully lyrical. In discussing Lerman’s “Family Album” exhibition and particularly the wonderful little painting, “Baba Sonya and Josef with horses (date and place unknown), “ 2017, a prominent Detroit artist said “This is a very brave exhibition and she learned to paint marvelous paintings doing it.”

Faina Markovna Lerman is a multi-talented artist and cultural activist and “Family Album” isn’t simply an exhibition of her artistic talent as a painter but illustrates her broad view of personal identity and our collective history.

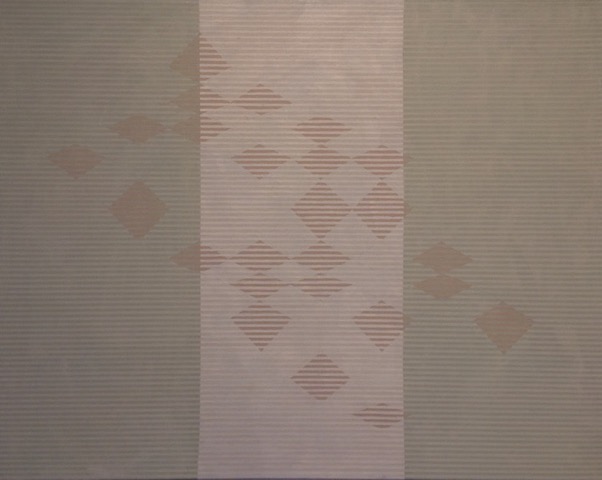

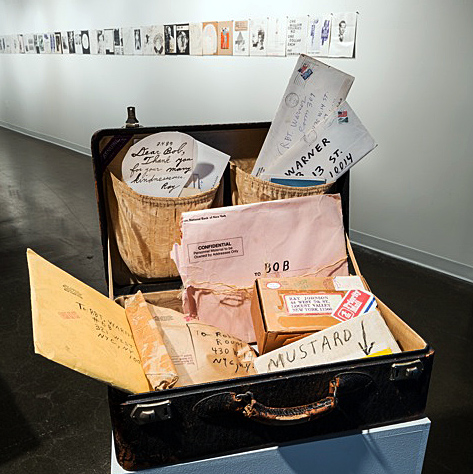

The exhibition is punctuated by a few simple family possessions– original stools, linens, baby blanket and Russian Nesting dolls (Matryoshka)– that were brought from Russia when her family migrated to Detroit in 1980. The Latvian symbol for growth, fertility and prosperity, which is on the cover of her family album is reproduced on the wall of the Cave Gallery.

Cave through 5/12 17

Russell Industrial Center 1600 Clay St.

Building Four-Third Floor

Detroit, Mi 48211