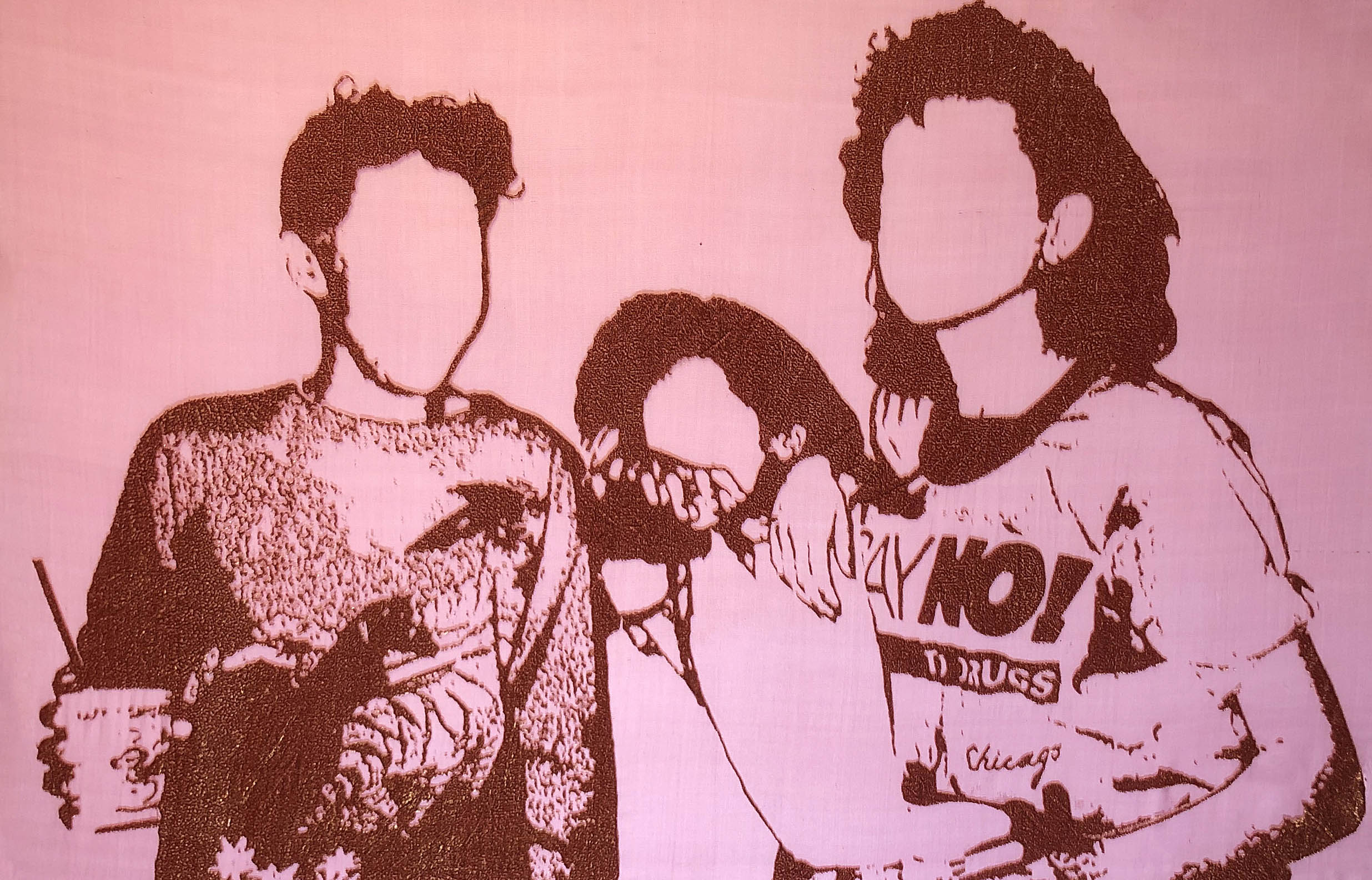

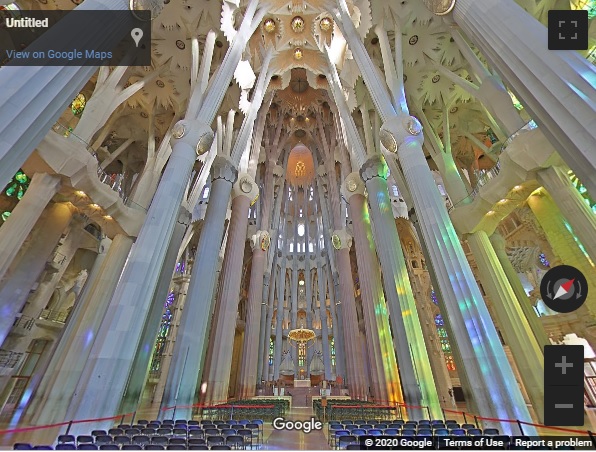

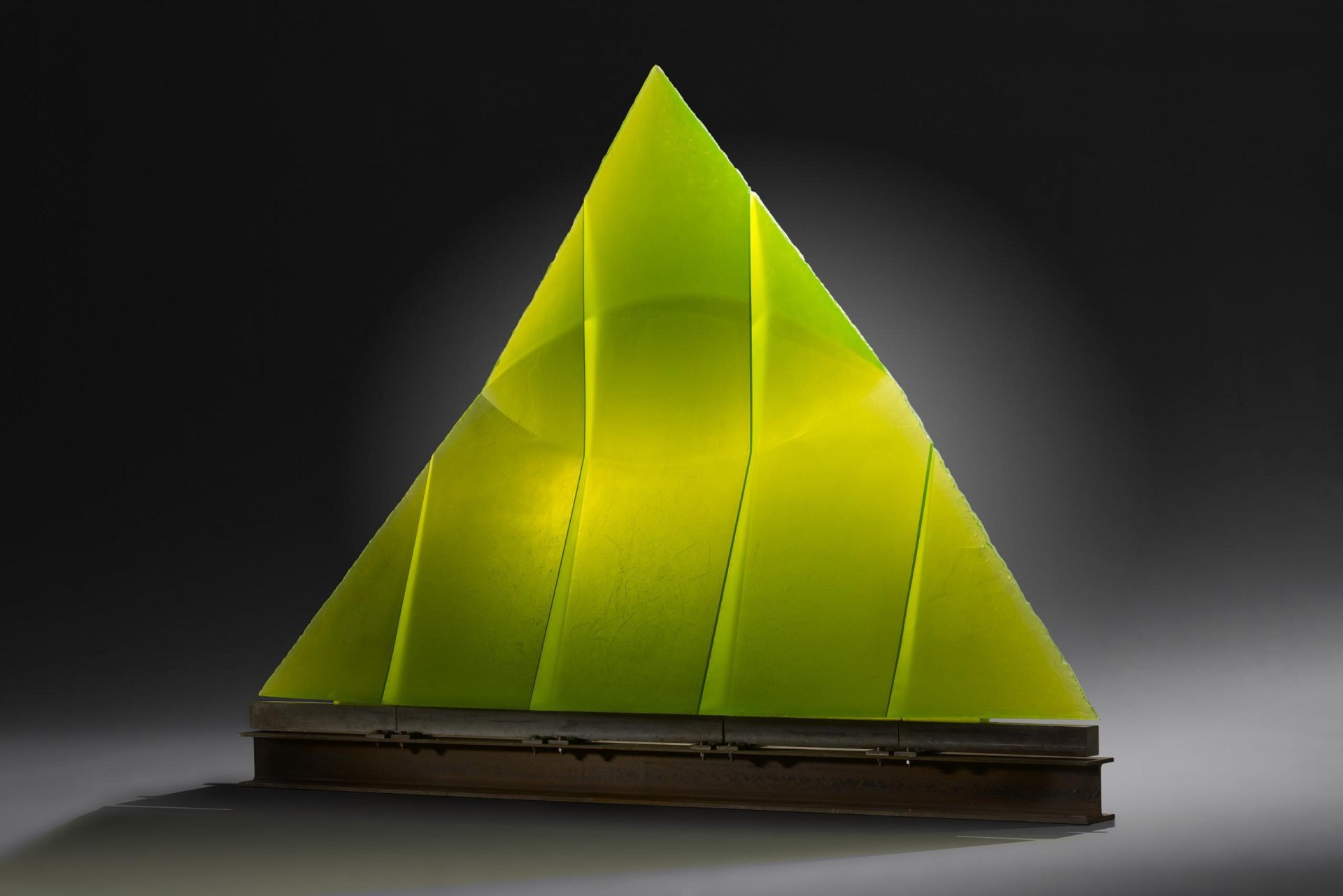

Install image, Black Matters, FIA

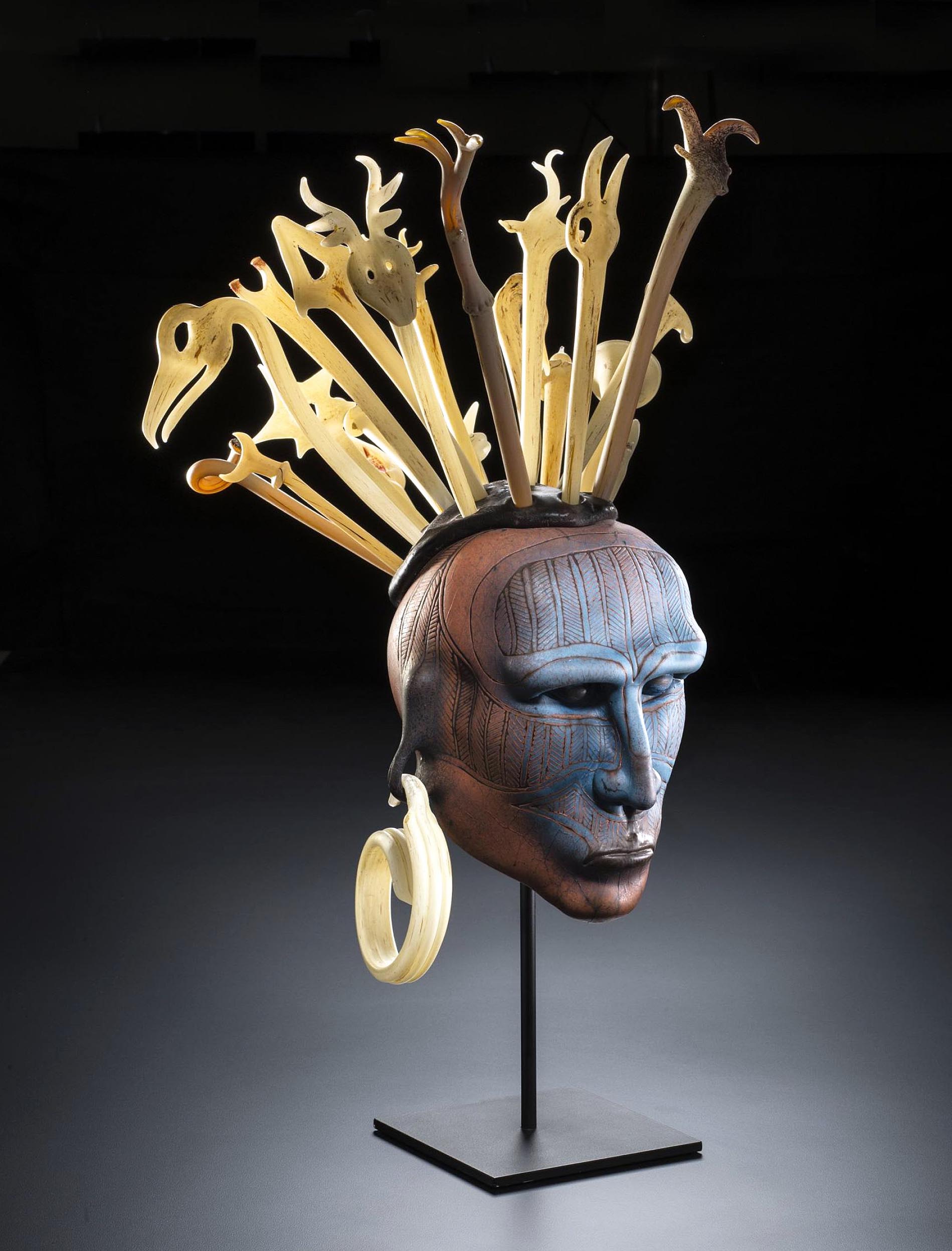

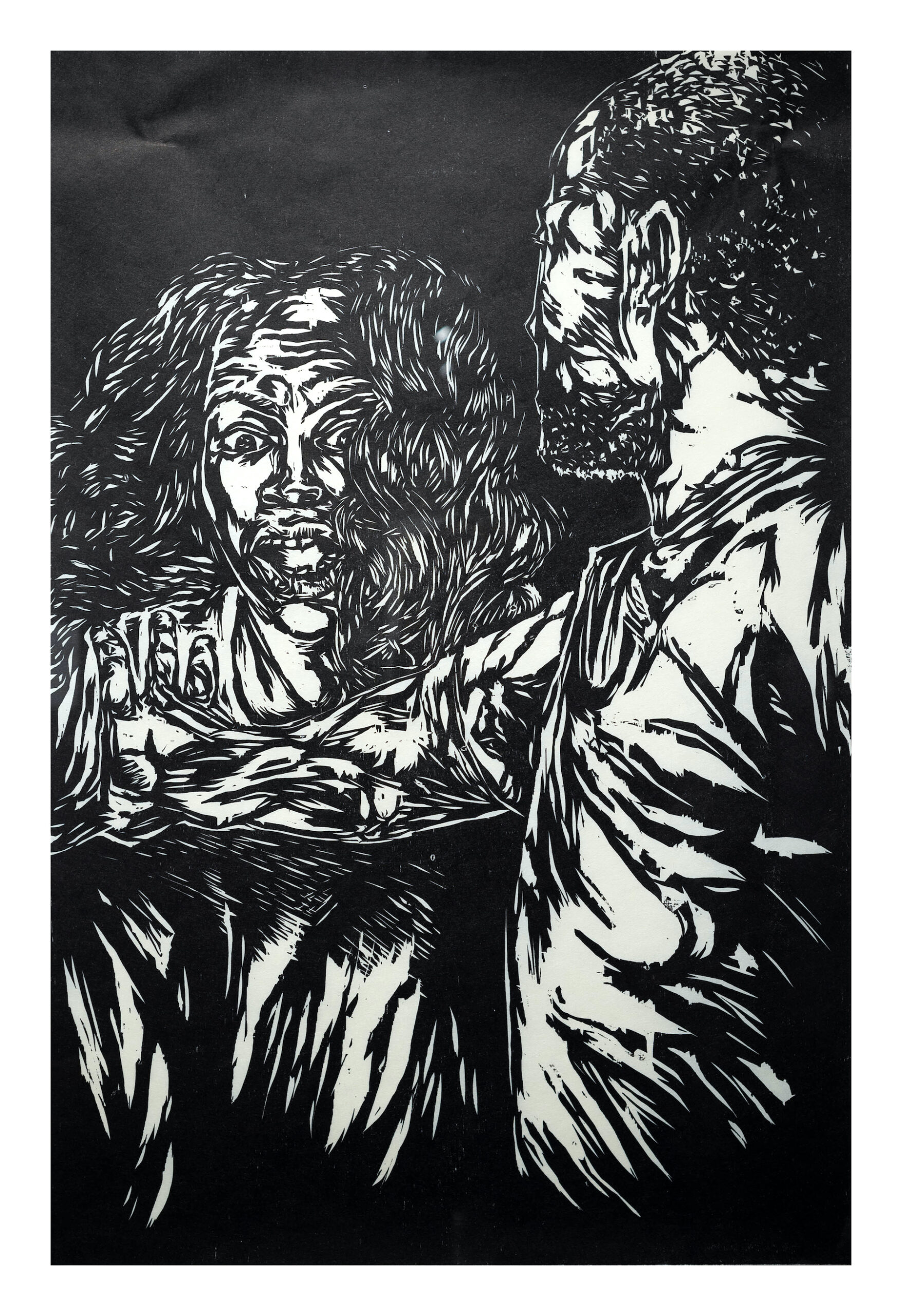

Chicago-based artist Matthew Owen Wead never intended Shooting Targets to be an ongoing series. Originally conceived in 2009, this body of work memorialized selected black victims of police violence spanning the years 1969 through 2009. But the deaths of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Ahmaud Arbery earlier this year sadly keep this body of work perennially relevant. The thirteen works from Shooting Targets comprise the bulk of the exhibition Black Matters currently on view at the Flint Art Institute, a moving and considered exhibition of life-sized woodcuts that manage to cross into the realm of performance and conceptual art.

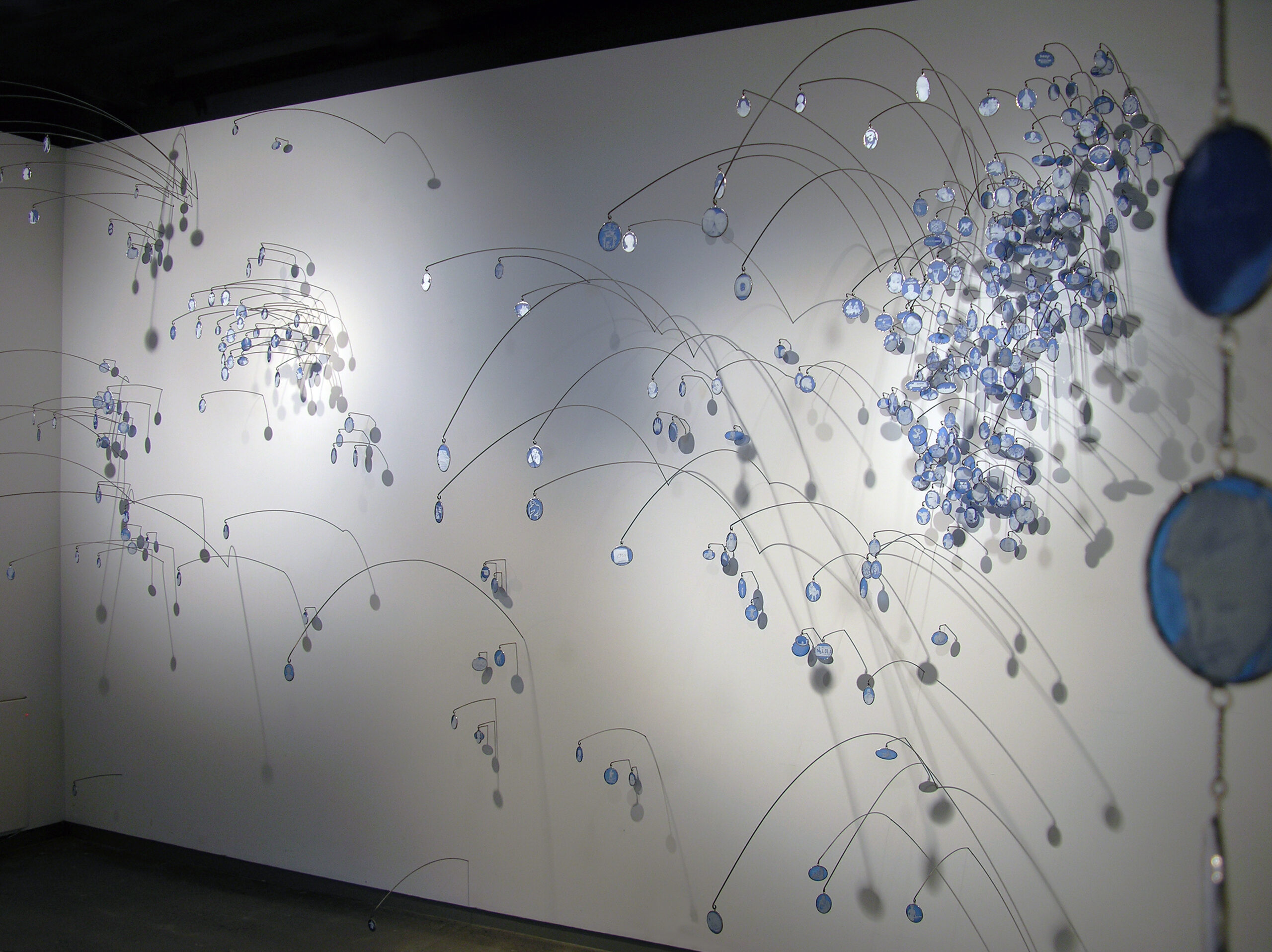

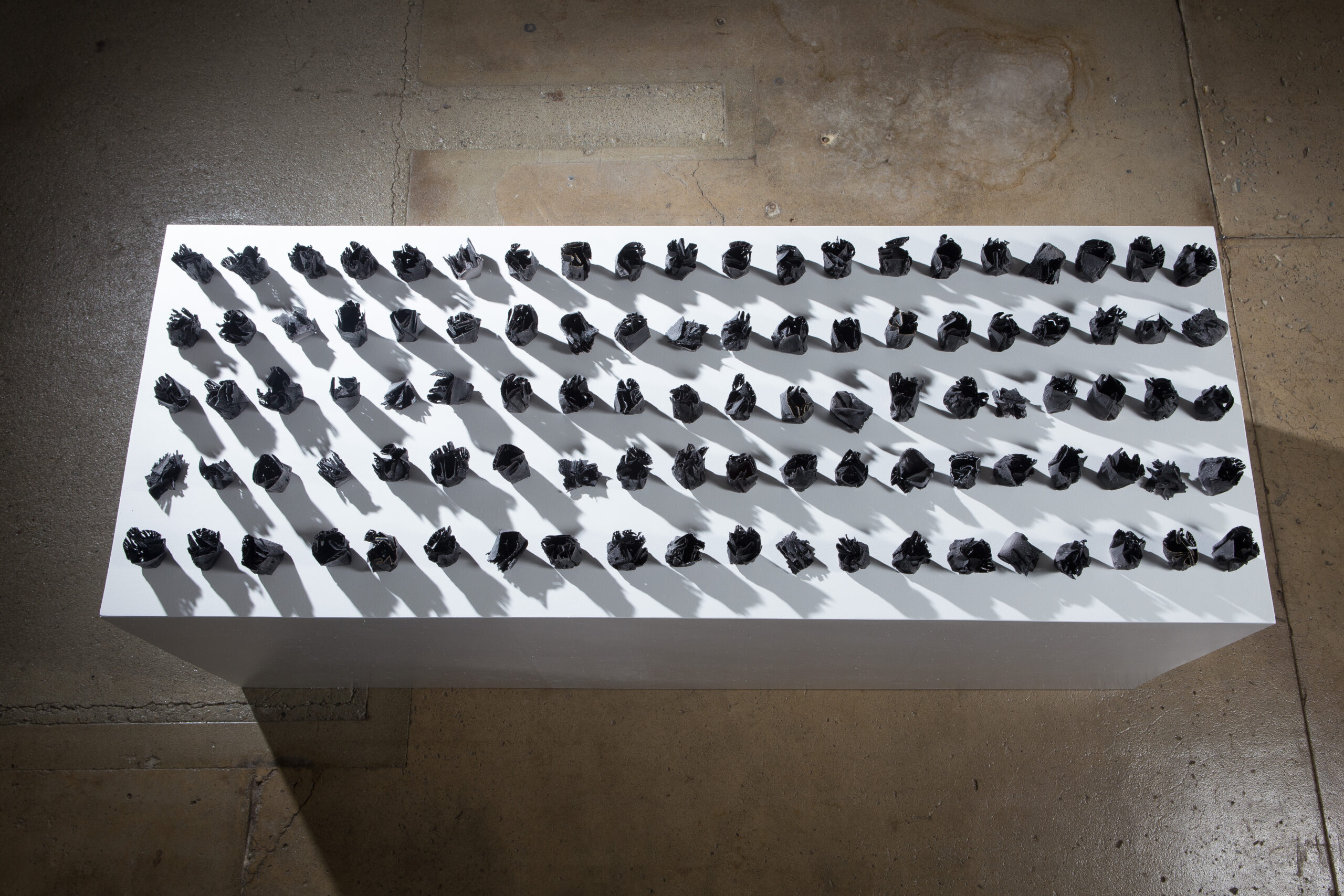

Occupying the FIA’s single-room graphics gallery, Black Matters consists of sixteen large woodcuts depicting black victims of police or vigilante violence; each print shows a black figure against a stark, white void, echoing the nearly universal formula for a typical target at a shooting range. Using himself as the model for most of the prints, Wead imagined the possible expression and posture of each victim in the moment before their death. Revealingly, it’s not necessarily always fear or panic we see; the five bullets that struck the mentally disabled Ronald Madison were fired into his back, for example, so some of these victims couldn’t react to what they didn’t expect. Each image is accompanied with didactic text on the wall relaying the story of each victim.

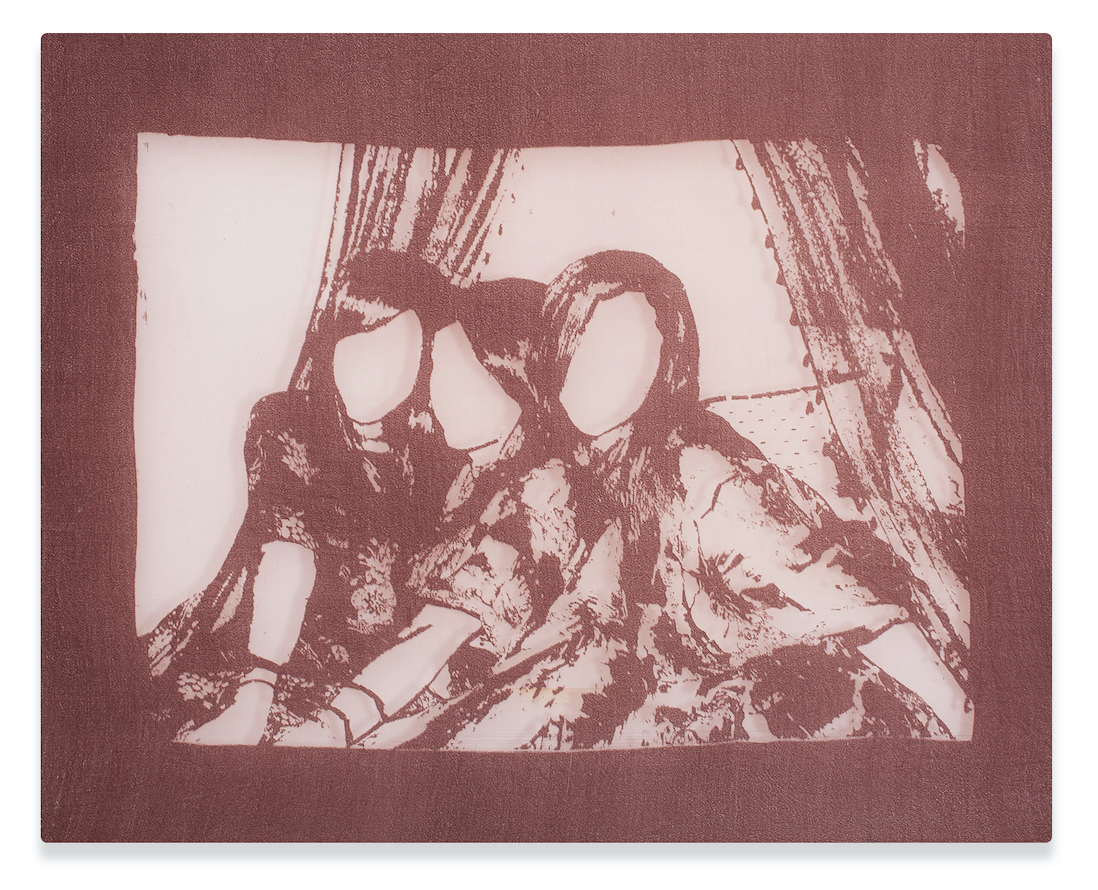

Matthew Owen Wead, American, born 1984 Breonna Taylor, 2020 Woodcut on paper 36 x 24 inches Courtesy of the artist

These works are confrontational in scale and certainly make a strong statement presented together as an ensemble, but their size also references the approximate size of a target at a shooting range. And we see each individual only from the waist up, also a conscious allusion to a target. Close inspection of some of these prints reveals actual bullet holes in the print corresponding to the number of times each victim was shot.

Stylistically, these works conscientiously betray the influence of early 20th century expressionistic woodcuts, particularly the visceral and emotionally charged works of Kathe Kollwitz, which Wead acknowledges were a formative influence on his work, along with the dark and visually punchy works of the Baroque painter Caravaggio.

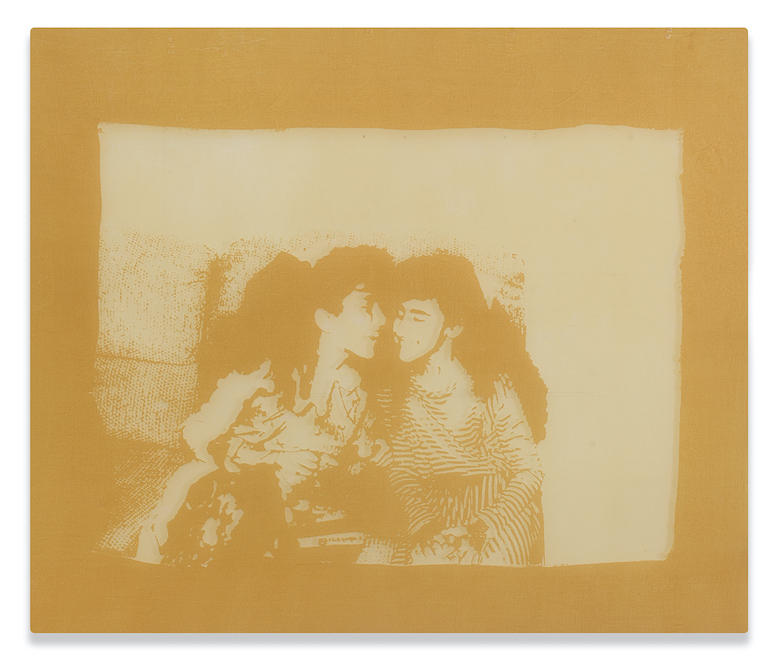

Matthew Owen Wead, American, born 1984 Johnny Gammage, 2009 Woodcut on paper 36 x 24 inches Museum purchase, FIA

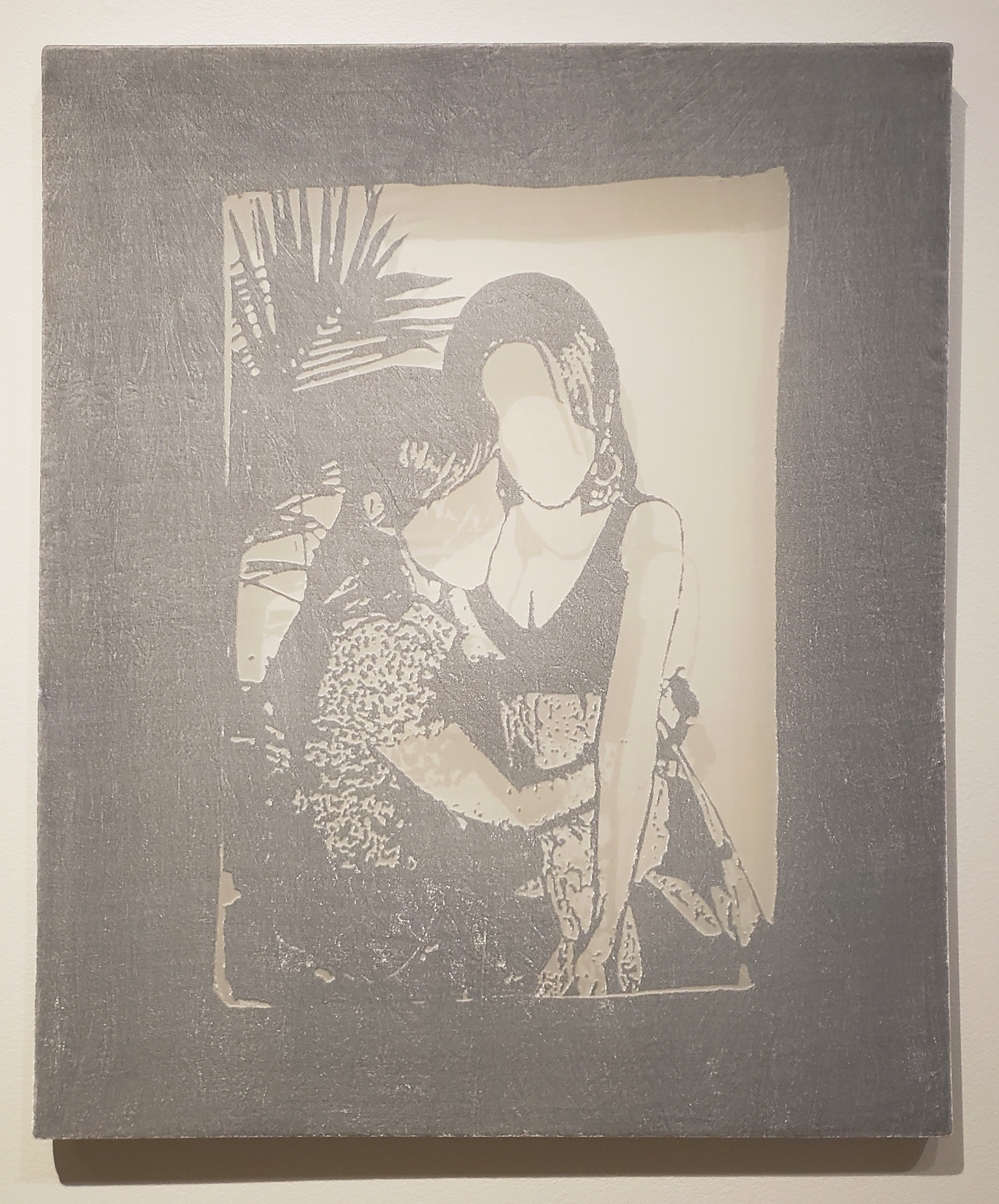

All of these works apply expressive linework. The agitated undulations and swirling light and shadow that appear on the jackets of Michael Pleasance and Khiel Coppin seem to help externalize their states of mind and underscore the drama of the moment, for example. And the knee on George Floyd’s neck is rendered abstractly as a frighteningly oppressive network of chevron lines which consume half the page. But there’s also an understated elegance in some of these images, as in the portrait of Ronald Madison, his back rendered with sinuous linework and deft application of light and shadow.

Matthew Owen Wead, American, born 1984 Ronald Madison, 2009 Woodcut on paper 36 x 24 inches Museum purchase, FIA

Both this exhibition’s title and font carry subtle references. Black Matters, of course, references the Black Lives Matter movement. But the “B” and “M” in Black Matters double as a 3 and a 5, wittily referencing the Three-Fifth’s Compromise which emerged from the 1787 Constitutional Convention, a policy that determined that in assessing the populations of each state, slaves would be counted as 3/5 of a person. The title and the 3/5 fraction together also subtly make the point that addressing systemic racism should always be a priority, not merely in those moments when a particularly sensational video happens to go viral.

Matthew Owen Wead, American, born 1984 George Floyd, 2020 Woodcut on paper 36 x 24 inches Courtesy of the artist

Install image, Black Matters, FIA

This show demonstrates that police brutality has been a problem well before George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbey unwittingly became names with which we are all familiar. Personally, I found it sadly revealing that almost all of these individuals were people I had never heard of before, suggesting my own relative ignorance of the history and the scope of the problem. Black Matters is a considered, moving, and pathos-laden exhibition, and it’s also an exhibition that shouldn’t have to happen.