Detroit Photographer has a Survey Exhibition of Work at the Halsted Gallery

Installation, Bill Schwab talking at open, 2018

Photography celebrates its 180th anniversary in 2019. This art form has fascinated us from its early beginnings with its ability to record time and aide our memories of people, places and objects. Photographs are magical things, credited with the power to steal a person’s shadow and provide a mysterious interaction of silver and salt akin to alchemy. That was pre-digital era, of course.

If you are anywhere near my age (and studied art in the 1960s) you may have taken a class in photography in your college years. You may have purchased a Pentax, Cannon, or Nikon 35-millimeter single lens reflex (SLR) camera and exposed a series of rectangles that captured an image of your family, friends and possibly your pet. After loading the camera and recording images, you rolled your black-and-white Tri-X film back into its cannister, removed it in a darkroom under a mysterious red light, and developed the celluloid impressions, each producing a negative image. The negative was then placed into a photo enlarger which projected a lit image onto photo sensitive paper, usually Kodak or Afga, creating a sensation that when wiggled around in a developing solution, magically forms an image right before your eyes. Life’s moment became concentrated, condensed and captured in a split second of time.

Bill Schwab, Metropolitan, Gum over Platinum Print, Detroit 2012

The Halsted Gallery was the only photo gallery in the Detroit metro area back in the early 1970s and, as part of the gallery archive, there are letters from photographers whom Tom Halsted represented, including: Henri Cartier Bresson, Andre Kertesz, Edward Weston, Edward Steichen, Ansel Adams, Berenice Abbott, and Imogen Cunningham to name only a few. In the year 2000, the Halsted Gallery had an opening for Bill Schwab, who was then a young and emerging photographer. The exhibit included small prints made from long exposures in the early morning fog of Belle Isle, Detroit. I bought his small, beautiful 36-page book and a limited-edition signed print.

Bill Schwab, House on Dearborn Street, 30 x 40″ Pigment Ink print, 2016

Fast forward to December 1, 2018, where the Halsted Gallery, now under the ownership of Wendy Halsted Beard, has reopened in a new location and mounted an exhibition, Relative Importance, of Bill Schwab’s photography that covers his work for the past two decades, including his more recent digital, aerial and wet plate collodion photographs. As professional and artistic photography still exists in this world of “everyone is a photographer,” Bill Schwab has endured with a prodigious reputation that many admire and he rightly deserves. Just because we all have smart phone cameras doesn’t mean we can compose, acutely observe and most importantly understand light. Circumstantial light considers not only all the properties and behaviors of natural light, but also how that light interacts with the objects around (you), transforming those objects into light-shaping tools.

Bill Schwab, Van Road Stars, 30 x 40″, Pigment Ink print, 2017

The first digital camera was created by Steven Sasson of Eastman Kodak in 1975, but the first consumer products didn’t arrive until the late 1980s and early 1990s. It wasn’t until 2010 that digital cameras were integrated into smart phones and by 2003, digital cameras out-sold film cameras. According to Info Trends, 1.2 trillion photos were taken in 2017. The technological change has had a tremendous effect on photography and photographers, but that is not to say it hasn’t been a natural advancement of capturing an image. Schwab is a good example of how photographers have embraced the new technology and used its tools as leverage to produce new kinds work. The digital image Van Road Stars, is a good example of how the manipulation of light and exposure can produce a rather engaging image, in part due to scale and incredible detail.

Bill Schawb, Mack at Lennox, Pigmented Ink Print, Detroit, 2016

What makes this Mack at Lennox image interesting has nothing to do with the recording device, but rather the sensibility to light, color and thought. You end up asking yourself how odd is that? Was it an ice cream stand or a dairy shop? But the cow has horns making it either a he, or a she. Formal in its composition, he makes the print large, 30 x 40 inches, which adds to its strength as a photograph. And then there is the light. Where is the light source coming from? Did he set a light up high against the darkened sky? These considerations are what set an artist apart from your average snapshot taker..

Bill Schwab, Five Trees in a Field, Pigment Ink Print, Detroit, 2016

Bill Schwab was early to take an interest in drone technology, something that most professional photographers now consider a necessary tool. He has a series called the Human Stain, largely made up of a decade of images taken of crumbling farm houses in rural areas, but this aerial image is of five trees with low light shadows and tractor trails that become the marks of visual artists with respect to placement and composition. It provides the viewer with a different point of view of the landscape, something that painters have been doing for hundreds of years.

Bill Schwab, Tidal Flooding – Hofn, Silver Gelatin Print, Iceland, 2015

Photography captures reality in distinct ways that were rarely available to painters. There once was debate over whether or not photography is fine art? I am not sure when that got answered, but the answer is clear: yes and no. If you’re photographing a still life for a garden magazine or a car for a showroom brochure, it is commercial photography. But when you are making abstractions, as Andre Kertesz or Ernst Haas did, or capturing precious moments in time based on light and composition as Henri Bresson did, it is fine art. The difference might be analogous to the difference between illustration and painting, although in the case of Norman Rockwell, the debate drags on, at least in some critics’ minds.

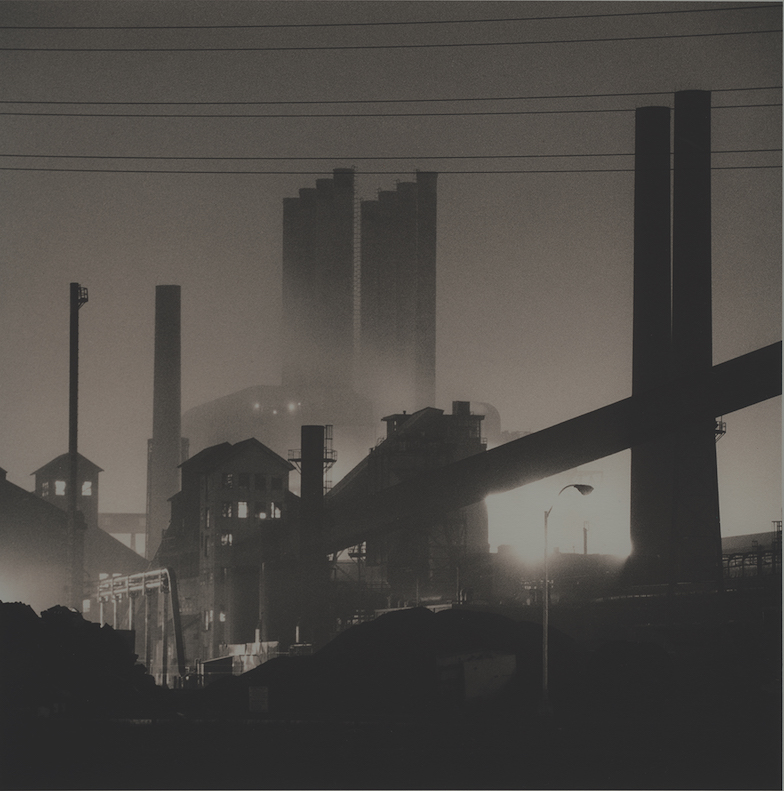

Bill Schwab, Rouge Steel, Silver Gelatin Print, 1994

Beginning at an early age, Bill Schwab developed an interest in photography with his Kodak Brownie camera and a home darkroom kit he got from his father as a gift. Like they say, give a person a fish and it’s a meal for that day, teach him how to fish, and it’s a lifetime of meals. Photography is Bill Schwab’s life, and great photography is about the depth of feeling, not the depth of field.

Bill Schwab earned his B.F.A in photography from Central Michigan University and worked for a short while in NYC assisting commercial photographer Alen MacWeeney before traveling the world as a commercial photographer. He has taken students of photography on workshops to Iceland, founded the Northern Light Press and coordinates the Photostock Festival yearly each June, changing and influencing photographers in his path. He has published four books on his photography, and his work is part of many museum, corporate and personal collections.

Bill Schwab, Relative Importance, at the Halsted Gallery runs through January 30, 2019