Carole Harris, University of Michigan, North Campus Research Center Rotunda Gallery, Installation Image

Talking in layers: walking into the enormous and alien territory of the University of Michigan’s North Campus Research Center to see the exhibition “Bearing Witness,” the quilt works of Detroit artist Carole Harris hanging in the building’s Rotunda Gallery. Dramatically lit, a series of Harris’ dazzlingly colored fiber works punctuate the security-conscious, antiseptic space. It is a research facility that was formerly Pfizer Pharmaceutical (think Revolutionary anti-cholesterol med Lipitor that paid for the amazing building complex) and that, after the economic “downturn” of the ’80s, was purchased by the University of Michigan to now serve primarily as a medical research complex.

Harris’ brilliant, lively and layered textiles offer a shocking, perhaps painful contrast to the generic, monochromatic, modernist architectural surroundings of the NCRC building. As a child growing up in Detroit, Harris was taught embroidery and stitching by her mother, and, being “height challenged” and quite petite, she learned to make her own clothes so they would fit properly. In high school at Cass Tech she studied music and science before settling on art, and, after graduating from college in 1966, she began an interior design practice that she maintained until recently.

In an ironic twist, her magnificent, globally influenced art looks almost captive in this sequestered, post-industrial landscape. It’s a long distance from Harris’ vibrant life in Detroit to the strange, emptiness of the medical research center.

In a recent talk at Detroit’s Charles H. Wright Museum, Harris talked about her evolution as an artist and about deciding in 1966 to make her first quilt for her upcoming marriage. For a start, she used the simple, standard “pin wheel” pattern, and for “stuffing” used an old blanket: humble materials for a special moment. It’s a tradition for quilters to commemorate a birth or marriage by making one, and it was an auspicious moment for Harris and her husband, the playwright Bill Harris, the beginning of a marriage that has endured for over fifty very creative years. While maintaining an interior design practice, she kept up her chops as a quilter and, like the jazz musicians she regularly honors in her quilt designs and titles, she played her scales: scissoring, stitching, splicing, editing, and learned her art form to perfection.

Harris’ fiber pieces at the Rotunda Gallery are a retrospective of the last twenty-five years or so of her work and feature what seem to be breakthrough visions for her. After years of using traditional forms, she recently began experimenting with works inspired by such diverse sources as the African Yoruba tribe’s Egungun textiles, Japanese Boro or “patchwork” folk textiles, architectural spaces derived from such American Abstract Expressionists as painter Richard Diebenkorn (especially his “City Scapes” and “Ocean Park” series), her childhood memories, or the storied erosion of historical buildings of the city in which she grew up, all with the astonishingly inventive, constant background soundtrack of black American music. In the process, Harris has quietly become an American master in a medium nurtured and influenced by black rural culture.

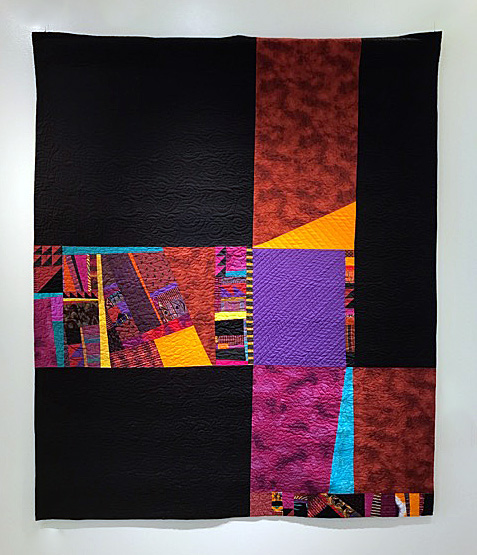

Carole Harris, Textile, Straight No Chaser, 60 x 69” 2006

The early work at the Rotunda Gallery reveals her break from traditional quilt patterns and shapes and, like much of the painting of the ’80s and ’90s (by Elizabeth Murray, Kenneth Noland, Frank Stella, et al.), explores ways of sculpting and lifting three dimensions to the flat surface of an abstract painting. “Outside the Lines,” 1994, posits an irregular shape, with a broad swath of negative space, corded fabric and loosely hanging strips, to create a sense of movement suggesting Harris’ homage to a Yoruba Egungun ceremonial dance that celebrates departed elders. Despite the radical break, Harris still uses basic quilt-making components such as individually composed “squares” and elaborate stitching to give texture and amazing painterly pattern to the surface.

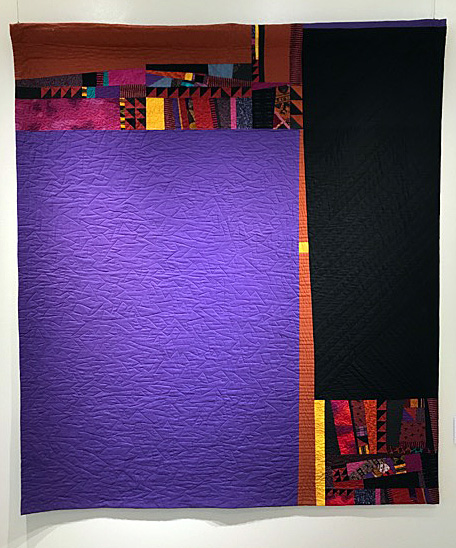

Carole Harris, Textile, Way Across Town, Textile, 59 x 70” 2008

There are two straight-up stunning works that employ hard-edged, geometric shapes of vibrant color balanced by coal-black negative space: “Way Across Town,” 2008, and “Straight No Chaser,” 2006, both in homage to Thelonious Monk, and that show Harris to be a daring colorist with both quilts centering a rectangle of electric purple supporting an array of oblique wedges and squares of oranges and reds. Not always a compliment, to be called a colorist sometimes implies that one is artistically not up to snuff, but this is hardly the case, as both of these works feature eye-popping geometric invention, and there’s real graphic genius operating here. With their daring, geometric slashes and exploration of architectural space, they might even reference the agitprop designs of the great Russian constructivists El Lissitsky and Rodchenko, from whom Diebenkorn, one of Harris’ honored influences, certainly learned. Throughout this visual musicality Harris keeps up an overall rhythm with a running stitch, sometimes with curving arabesques, sometimes with an angular geometric backbeat.

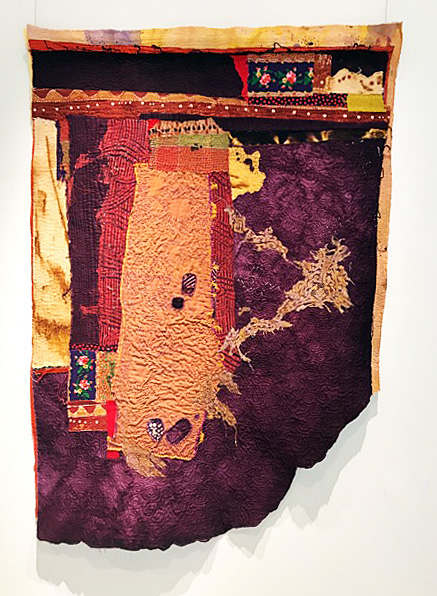

Carole Harris, Textile, From Before, 58 x 45 2013

Harris’ quilts from the last couple of years suggest the influence of the Japanese phenomenon of Boro patchwork clothing. Japanese peasants, especially in the 19th century, being economically challenged, would patch their clothing with remnants of old, worn-out garments, creating a remarkably beautiful folk style of dress. Using the running stitch, sashiko, to bind the patches to the old clothing, they would create a decorative pattern. There are six works in “Bearing Witness” that use the Boro technique. “From Before,” 2013, uses a layering of remnants or swatches — one is hand-stained with a radiating pattern– that overall suggests a geographical mapping. The irregularly shaped “Other People’s Memories,’ 2016, layers found remnants of clothing in various colors and patterns and combine machine and hand stitching to create what feels like a fragment of an ancient textile.

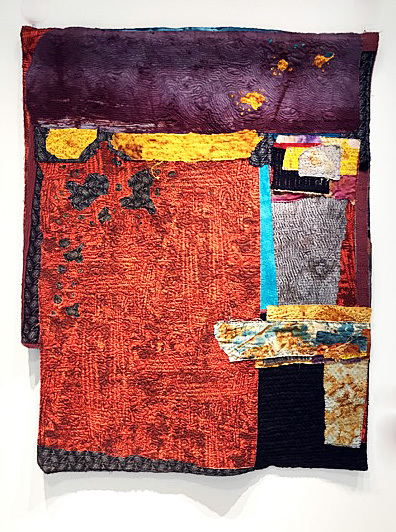

Carole Harris, Textile, Other People’s Memories 39 x57” 2016

Likewise, three small seasonal “sketches” — “Spring Ascending,” 2016, “Fall Etude,” 2015, and “Winter Etude” 2015 — combine stained remnants, machine and hand stitching, burnt holes, and hand-stitched florets, to image topographical maps that indeed, in their lyrical beauty, echo Chopin’s Etudes themselves.

The last piece to come out of Harris’ studio just for the exhibition was indeed the title work.

“Bearing Witness” is a tour de force of contemporary image making. It amalgamates not only Harris’s quilt-making magic with the disparate influences of her far-reaching eye, but is a profoundly rich metaphor for the deep struggle of living, of the balancing of life’s experiences, of listening and watching and caring for the world. This sublimely visual layering of color, shape, and line is not only an act of art but — what resonates through in this process of layering the fabric of life by hand— is an act of deep caring. The title “Bearing Witness” is thus not misplaced on Carole Harris’ practice as a whole.

Carole Harris, Bearing Witness, Textiles, 42 x53” 2017

“Bearing Witness” continues at the Rotunda Gallery through August 23

U-M North Campus Research Complex, 2800 Plymouth Road, Building 18, Ann Arbor, MI 48109