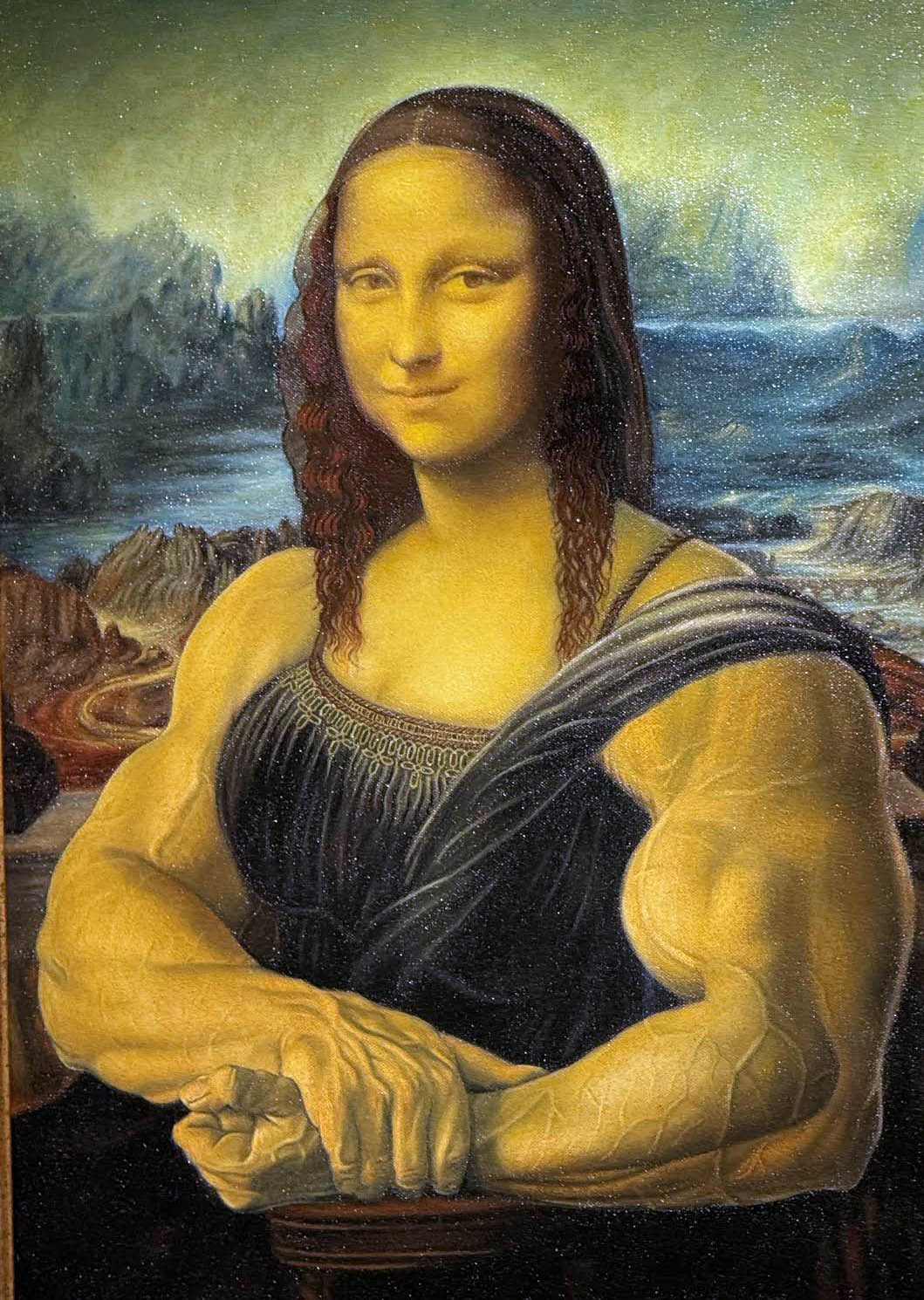

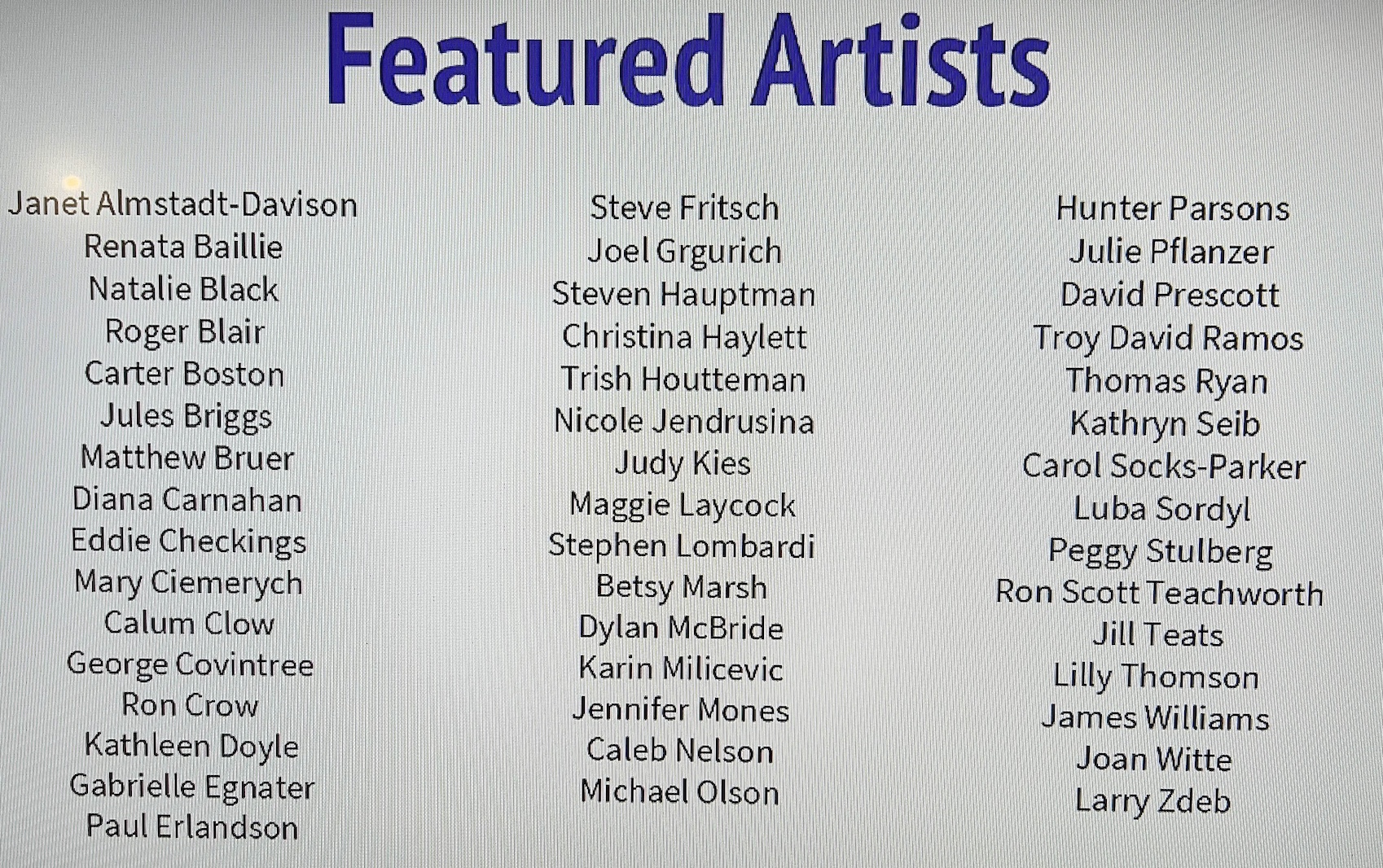

Installation image, courtesy of Trinosophes

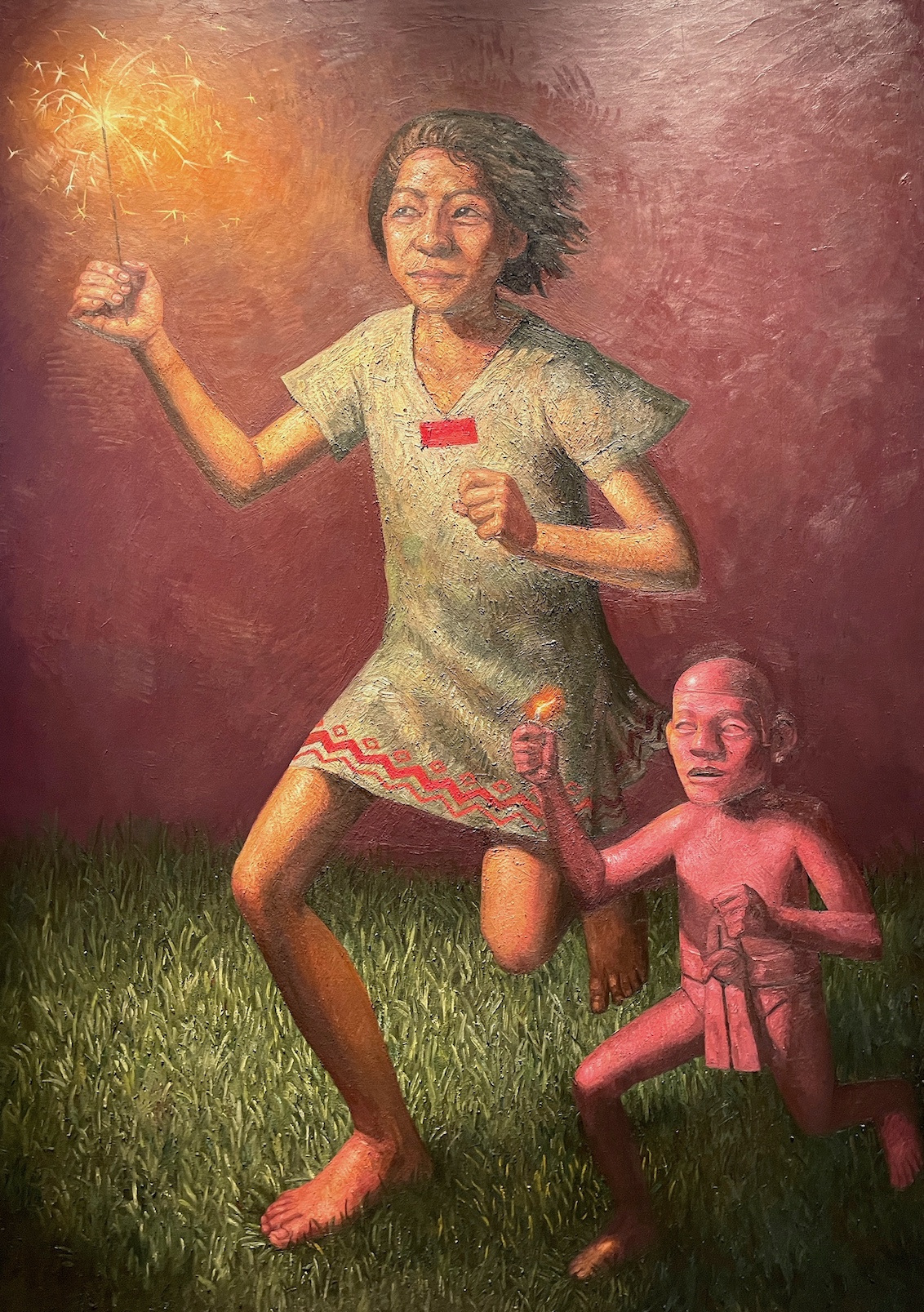

Trinosophes, the multidisciplinary arts space on Gratiot Avenue across the street from Eastern Market, is now featuring an exhibition of El De Smith, an erstwhile denizen of Detroit’s Cass Corridor area during the art movement’s vintage years in the 1970s. (Born in 1913, the artist’s death date remains unknown.) Smith’s “outsider art” on view, comprised of paintings, signs, and texts from 1970-76, the approximate years he lived amidst the territory of the Corridor artists, as evidenced by the several artists who held onto his works and lent them to the current presentation. In his introductory essay, Steve Foust asserts, “He gave away his works, saying that they were his communication to others.”

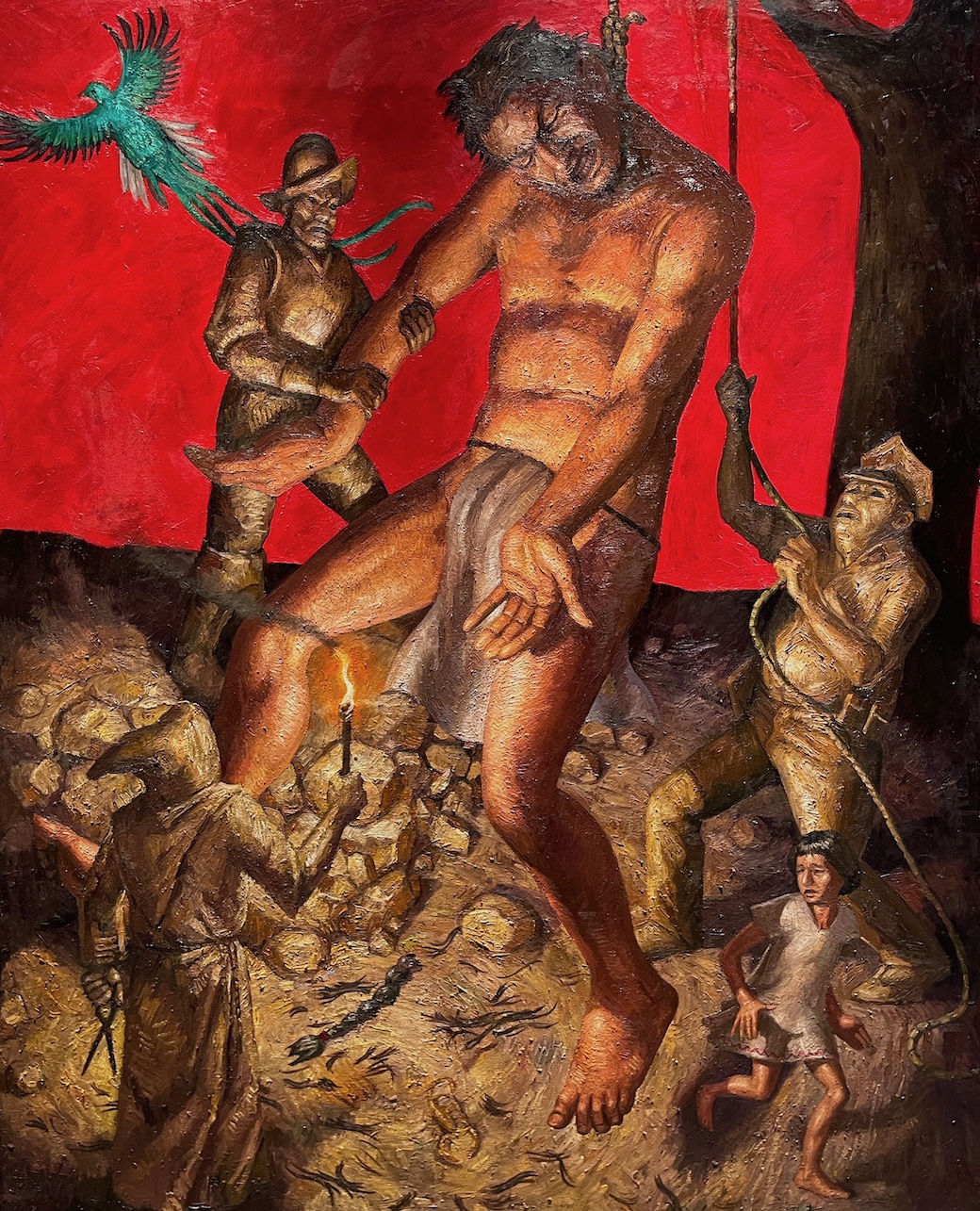

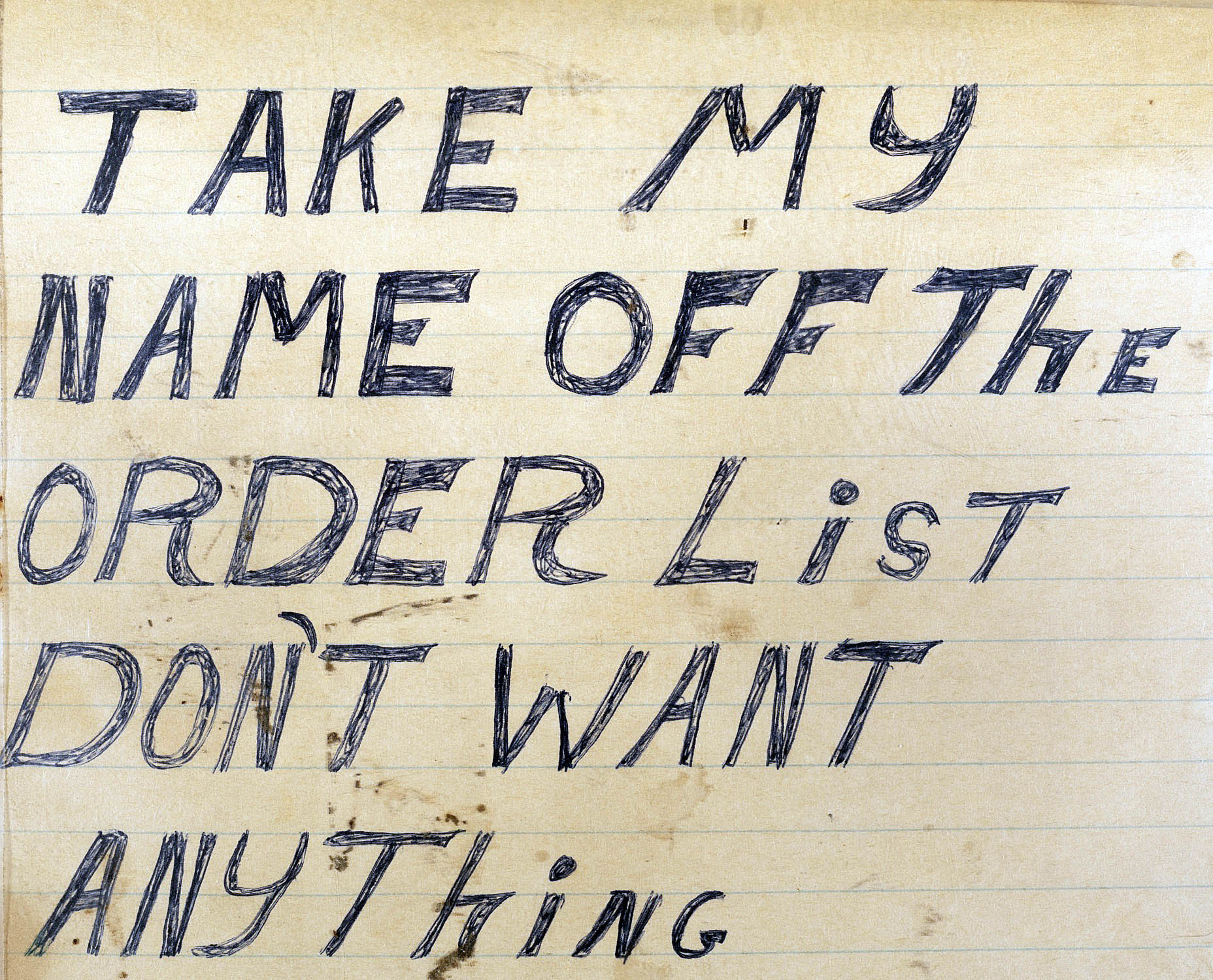

El De Smith, Take My Name Off the Order List Don’t Want Anything, n.d., ballpoint pen on paper, excerpt from a longer text.

The lengthy title of the show is, in fact, drawn from a typical text by Smith that expresses an emphatic point of view, as in: “Take My Name Off The Order List Don’t Want Anything.” Such a blunt declaration about unwanted interferences in his life is apparent in other texts and handwritten statements accessible to visitors in a file case displayed in the exhibition.

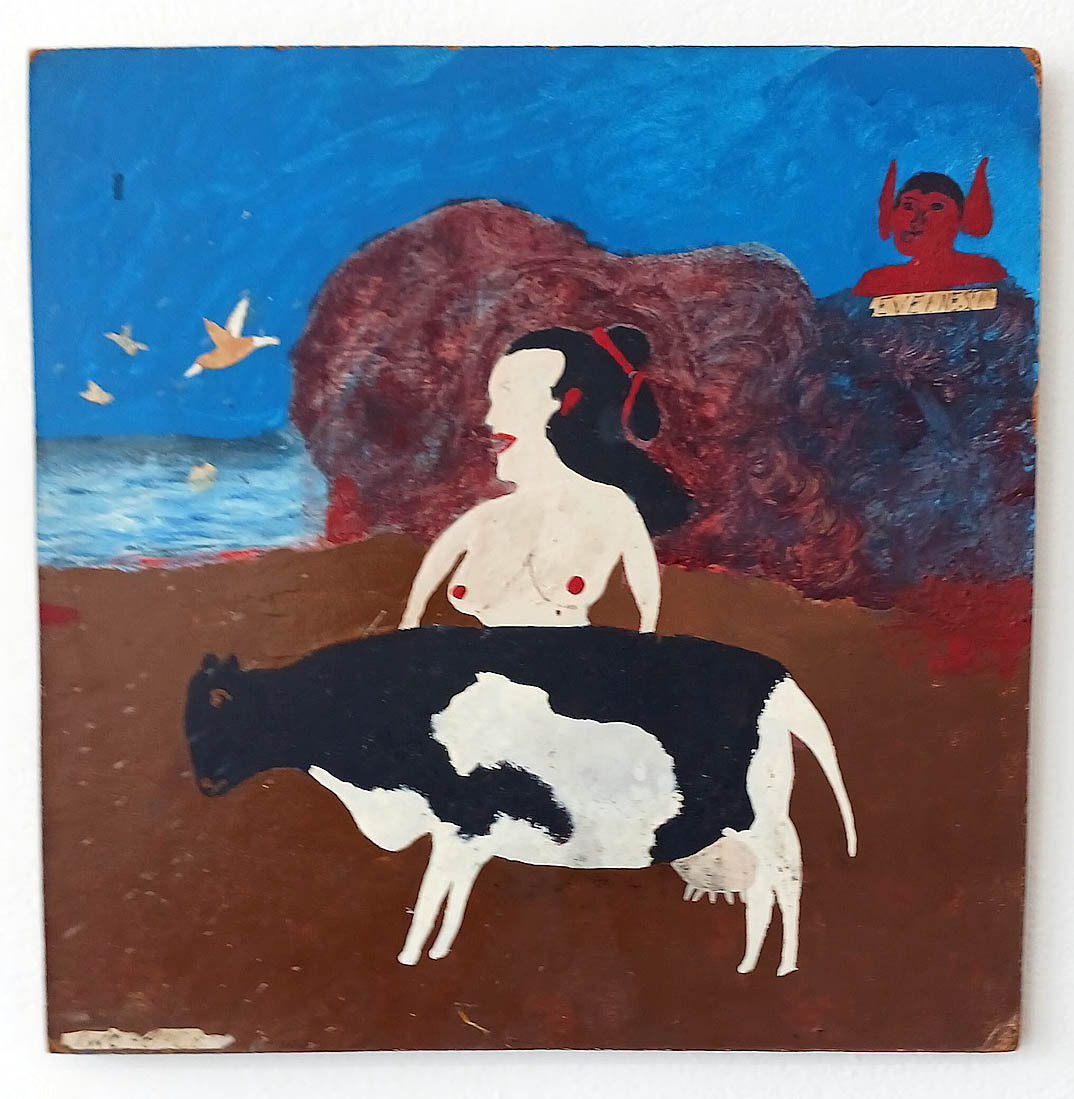

El De Smith, Untitled (Bull), c. 1972-74, paint on plywood, 11 x 27 in., Collection of Steve Foust & Nancy Bonoir

Smith’s pictorial imagery often features animals, many of them farmyard familiars such as cows, dogs, roosters, and bulls, often posed before solid, uniform backgrounds. In Untitled (Bull), the centralized image of a snorting bull is outlined against blue sky and green grass barely distinct from one another. The arc of the bull’s body is aptly echoed by the parenthetical curves of the sides of the plywood panel. And the clever, handwritten title affixed to Rooster to Wake One Up, pictures a rooster whose puffed-up body, and ostensibly harsh wake-up cries, literally obliterates most of the blue background.

El De Smith, Rooster to Wake One Up, 1973, paint on matboard, 12 x 13 in., Collection of Jim Chatelain.

Figural representations by Smith include a couple of friendly ghosts, three humanized bears from the children’s story, and several portrayals of that stealthy arch-enemy, the devil, aka Diablo, who is often (if not always) up to no good. In Two Holy Cows, a naked woman and a cow stand in the foreground of a landscape with the sea and a cliff as backdrop. At the far upper right, however, behind another of Smith’s affixed labels reading “Evil Nest,” a devil leers at the scene below, and the age-old story of Susanna and the Elders hoves into view as proverbial prototype.

El De Smith, Two Holy Cows, c. 1972-74, paint on Masonite, 13 x 13 in., Collection of Douglas James.

Another devilish depiction, Untitled (Devil with Painting), is the largest in the exhibition at three feet tall, and is delicately cut from sheet metal. Presented in profile, this devil seems elated as he trots along with a painting under his arm. Has he just completed his latest masterwork, or is he absconding with stolen goods? And true to form, in Untitled (Diablo with Book) the evil villain, teeth bared, hunches threateningly as he grasps his ill gotten treasure while poised atop a green hilltop depicted, somewhat unexpectedly for Smith, with swirling, expressive brushstrokes applied alla prima.

El De Smith, Untitled (Devil with Painting), c. 1972-74, paint on sheet metal cutout, 36 x 16 in., Collection of Jim Chatelain

Lastly, a human figure captured in a human predicament appears in a scene representing a dejected man bestride a looming chair. Hunched over, with a hand shielding his face, he remains unresponsive as the cartoon rabbit beside him absurdly queries, “What’s up, doc?” The rigid, towering blue chair on which he has collapsed, plus the hot, sultry red hue, vivify the emotional tenor of the setting. Is this perhaps a self-portrait of the artist undergoing a dark night of the soul?

El De Smith, What’s Up Doc, c. 1972-74, Paint on matboard, 17 x 23 in., Collection of Jim Chatelain.

The “paint on matboard” materials that Smith employs in this touching portrayal may have been scavenged and/or furnished by the Cass Corridor entourage, whom he knew and they him, as he dwelt among them. He traveled and camped out with them on occasion before leaving the Corridorian enclave in 1976. Indeed, Foust appreciatively summarizes the rediscovery of Smith’s art, concluding that, “He was a community member and Cass Corridor artist.”

Twenty works in all were rediscovered for this Trinosophes’ production curated by artist Jim Chatelain; many of the artworks on view were drawn from the collections of Cass Corridor artists identified in the checklist; and the hang was designed/installed by artist Dylan Spaysky. One hopes that additional works by El De Smith will be located in the future, whether tucked away in the Detroit metro area or found farther afield.

The El De Smith exhibition remains on view through May 25, 2025. Trinosophes is located at 1464 Gratiot Avenue. Parking is available at the front and back of the building. Hours are 10 – 3, Wednesday – Saturday.