Laura Magnusson, Blue, 2019

Water is a paradoxical thing, both sustaining and dangerous; it’s our origin, our literal lifeblood, yet it has a hundred ways of eroding our foundations and pulling us under. Canadian interdisciplinary artist, University of Michigan grad, and trained scuba diver Laura Magnusson considers water her collaborator: “supportive, receptive, restrictive, indifferent.” Her eleven-minute silent video Blue (2019), on view at the Flint Institute of Arts through December 30, is set entirely underwater — 70 feet below the surface of the Caribbean, in fact, off the shore of the Mexican island of Cozumel. Down there, the horizon disappears into an azure haze that hangs over the cyan-tinted sand of the nearly featureless sea floor. It’s an abstract environment, an open stage for a performance that Magnusson describes as a voyage “through the afterlife of sexual violence,” and “the impact statement (she) was never permitted to give before a court of law.”

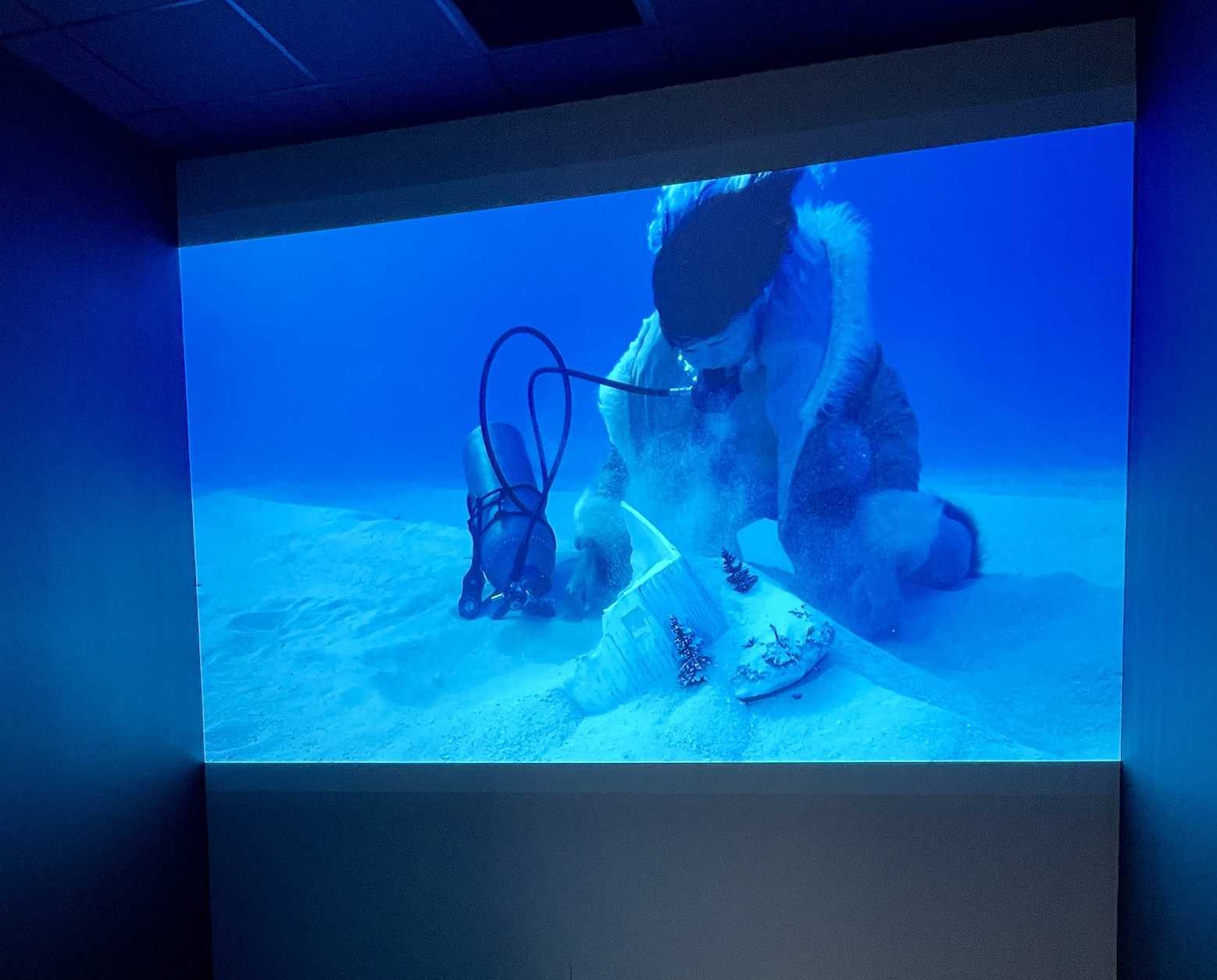

The video opens on Magnusson crouched on the seabed, wearing a winter parka with a fur-trimmed hood and matching snow boots that seem less incongruous than one might imagine in this alien environment. Magnusson begins to trudge through the course sand, leaning into the water’s resistance, carrying in one hand the large tank that’s providing her with air, and in the other a model of a corrugated metal building complete with pine trees and a porch. In the doorway stands a figure in black underwear, a miniature version of the artist.

Laura Magnusson, Blue, 2019

First Magnusson tries to bury the model building (which was looks to be broken, a corner or fragment rather than a complete structure), scooping sand up over it. She makes a few attempts to leap upward toward the surface, but sinks back down each time, descending to the sea floor in slow motion. She wrestles to remove the parka before appearing half buried in the sand still wearing it. Eventually we see the coat fluttering free through the water like a diaphanous sea creature. Magnusson crouches again, nude now but for underpants and a diver’s weight belt, encircled by the arc of her air tube.

Magnusson alternates between standing, crouching, and self-burial until the cycle is interrupted by a shot of the artist wearing a pained expression above the scuba regulator stuck in her mouth. The hood of the parka is pulled up over her head, and she’s framed by a black void as silver fish dart around her. Crouching again, she screams silently into the sea, bubbles streaming from her mouth. In a close-up, we see her fingers attempting to pry the miniature figure of herself from out of the doorway of the model structure. It feels like a breakthrough, but it’s followed by a literal reversal: the film starts moving backwards. Air retreats into Magnusson’s mouth and she retraces her steps as if pushed back by the current. In the end, the broken building remains planted in the sand, and the black void returns, minus Magnusson, with only the silvery-blue fish remaining. The video loops, and begins again.

Laura Magnusson, Blue, 2019

Speaking in a YouTube video on Blue, Magnusson reveals some of the thinking behind the piece. The model is based on the inn in Manitoba where Magnusson was assaulted; its small scale allows her to better grapple with the place, though she fails to completely bury it or wrest her miniature self from its doorway. The multilayered construction of the handmade parka, which the artist describes as “clamshell-like,” was inspired by the shell of “Hafrún,” a living clam discovered in Iceland in 2006 that was 507 years old — when it was killed by scientists who pried it open to determine its age. If the coat is protective, why shed it, unless it’s a hindrance as well? Why does Magnusson bury herself? Some sea creatures cloak themselves in sand as camouflage; does the artist want to protect herself, anchor herself, or disappear? Magnusson explains that her actions in Blue were not scripted, but developed during the performance and organized in the editing process. This is not a tidy, linear narrative of someone who’s conquered adversity, with a satisfying resolution and a prescription for a clear path forward; it’s a metaphorical document of a continuing journey toward healing, one Magnusson calls “circuitous,” “wandering” and, appropriately, “fluid.”