Square Peg, Round Hole, Hungry Ghost

One is reminded of the pre-eminence of painting as the pinnacle of fine art media- and its uncanny self-sufficiency- up to the late Twentieth Century when viewing Brenda Goodman’s decade-spanning retrospective at Center Galleries at College for Creative Studies. Coming face to face with the broad span of figures, forms, and grounds that float heavily through Goodman’s oeuvre unlocks a deep, visceral response. This is painting that tells me that I know nothing about painting. This is painting as it once was and is no longer. This is painting from the days when painting was a truly heroic undertaking- when works of profound genius that seamlessly roped form, material, surface, context, and narrative into an exploration that balanced on a knife’s edge between pure form and deep, expressive language seemed to roll right out of the minds of Goodman and her contemporaries, such as Philip Guston, Elizabeth Murray, Nancy Mitchnick, and Ellen Phelan.

The above-mentioned self-sufficiency that comes across in Goodman’s work is the result of visual engagement with the viewer’s experience, employing only one material to express a language that is both purely formal and not- that both dwells in and transcends the methods of its making- that feels (these works make one refer to a visual response as a feeling) like a foreign language heard in a dream that gradually becomes discernible as one listens to it.

Likewise, as one goes from work to work in Brenda Goodman: Selected Work 1961-2015, the development of her encyclopedia of symbols distills in different forms and contexts, its trajectory remaining intact despite the constant inversion of figure/ground and objective/nonobjective (these, I might add, are only two of the largest and most evident inversions- Goodman parses the notion of inversion, turning, twisting, and recasting through surface, picture plane, narrative, space, and form up to the horizon of the viewer’s vision and then, presumably, beyond it) that Goodman ropes into her exploration down the decades. It is this roster of forms and characters- Goodman has referred to them as “personal symbols”- that hauntingly parallel language in the aggressively visual, formal context of her work.

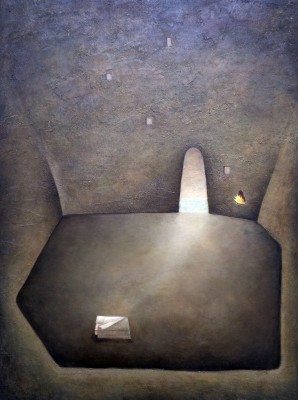

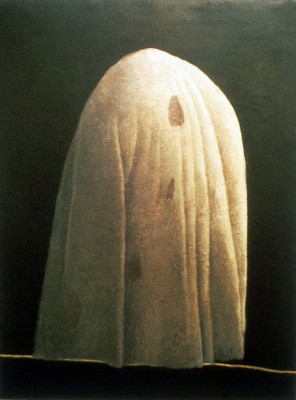

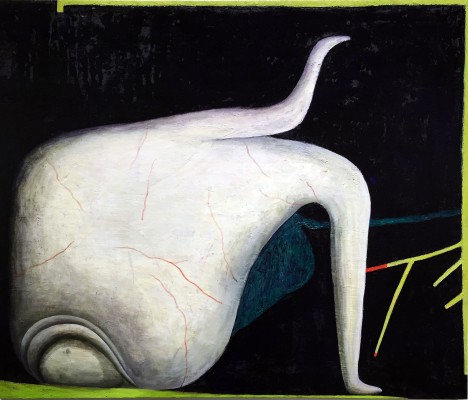

The figure makes its presence felt in various ways through the years spanned in Selected Work. Its earliest manifestations, in works such as The Race (1973) depict grotesque-yet-loveable mutations of human bodies into simplified intestinal forms with prehensile limbs and hungry mouths, clumsily filling minimal atmospheric spaces as they stretch and strain to work, express, and consume. These minimal spaces empty out intriguingly in a couple of works from the late 70’s though the forms of the figures remain, now sunk into ground space and half-camouflaged with light, as in Untitled (1979). Another untitled piece, one of the most striking in the show, is a smallish work on paper from 1981 depicting a rotund draped form that bears all the awkward heft of Goodman’s early organ-figure paintings, and yet floats across a deep black ground cut horizontally near the bottom of the picture plane to reveal a thin strip of earth-toned underpainting that reads like a tightrope. There are shades of Philip Guston’s Klansman romps here, but recast in an altogether more sombre, personal context.

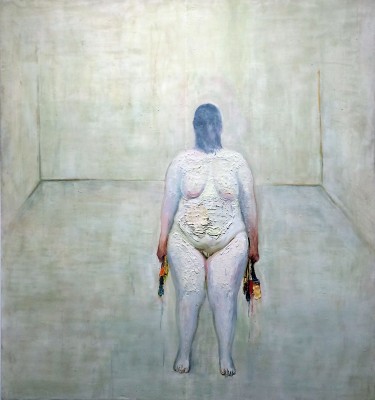

The figure fleshes out more representationally, in the same vague, thinly painted studio-type space, in a series of unforgiving self-portraits that progress through the 1990’s (an era marked by extreme hostility toward painting and explorations of the figure in particular that sparked an epoch of figurative painters such as Jenny Saville, Elizabeth Peyton, John Currin, and Lisa Yuscavage) to 2008. These portraits, which Goodman executed while struggling with her weight, depict a large, fleshy female figure ephemerally lodged among barely tipped-in canvas stretchers and vast pale space. The figure is heavy and fat, the flesh built up in crazy swaths and scorings of sick flesh tones, and yet floats- her feet are almost never visible, and her connection to the studio-like space is uncertain.

The organ-figure appears again around this time, undulating through dark voids and squirming beneath flat, saturated bands of color in a run of untitled works on paper that evolve through almost totally nonobjective color field studies shot through with drawing/painting marks, and coalesce again in Goodman’s most recent work on display, such as the taut, formally enclosed Euff (2015). Here, a pale, root-like figure waves two tapering limbs around a deep black ground, which it shares with pale, sharp slashes that read like unlit matches, creeping into the picture plane from the lower right. The figure’s limbs divide the picture plane into three petal shaped forms- looked at this way, the figure becomes the ground, and yet the sense of movement that radiates from it quickly re-establishes it as a figure. Is the form painted, or is the painting happening around the form? It’s a mark of Goodman’s genius that the two are constant, silently changing places. Her best work keeps the forms and the action vague enough that the interstice between figure and ground remains enticingly impossible to focus upon. It seems like such a practice, where the meat is in the surfaces, would preclude any meaningful figurative, symbolic, or contextual content. That’s another facet of Goodman’s genius. Her paintings are purely formal but not, intensely personal yet open, deeply symbolic and embedded in an experiential, bodily context, and yet ungrounded, floating, vulnerable to various points of entry and engagement. It is this quality that leaves the contemporary viewer in awe- the ability of Goodman’s work to function seamlessly on visual, emotive, and conceptual levels, with paint and surface as the only tools.

Brenda Goodman: Selected Work, 1961 – 2015 November 14 – December 19, 2015

http://www.collegeforcreativestudies.edu/community-outreach-and-engagement/center-galleries

“Brenda Goodman: A Life on Paper” Paul Kotula Projects, http://www.paulkotula.com