Olga de Amaral: To Weave a Rock at the Cranbrook Art Museum

Bogotá-born and based fiber artist Olga de Amaral is now receiving her first U.S. retrospective at the Cranbrook Art Museum in a joint curatorial venture with the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, the institutional hotbed of Latin American scholarship, primarily driven by well-researched exhibitions. This current show, which traveled here from Texas, is a rare treat since Latin American programming does not feature centrally in the Michigan cultural agenda.

By way of introducing the non-utilitarian textile practice of this Colombian artist to an audience mostly unfamiliar with her rich practice from the last five decades, the Cranbrook Art Museum commissioned a short video displayed in the entrance space, directed by Andrew Miller. Filmed in close-up in what appears as a single take, the artist directly speaks to the viewer about the essential role that color, texture, and structure, alongside the simplicity of a geometry of squares, circles, and triangles, play in her woven, braided, and knotted fabric “constructions” in space.

Such concerns are perfectly in keeping with the principles of an abstract artist whose series of works are distinguished by permutations in technique accompanied by a plethora of intricate color, texture, material, and shape variations developed throughout her career. In the 1960s, the planar tapestry-style weavings, often featuring a fringe above or below, allowed the viewer to look through the existing wool threads onto the support, the white wall.

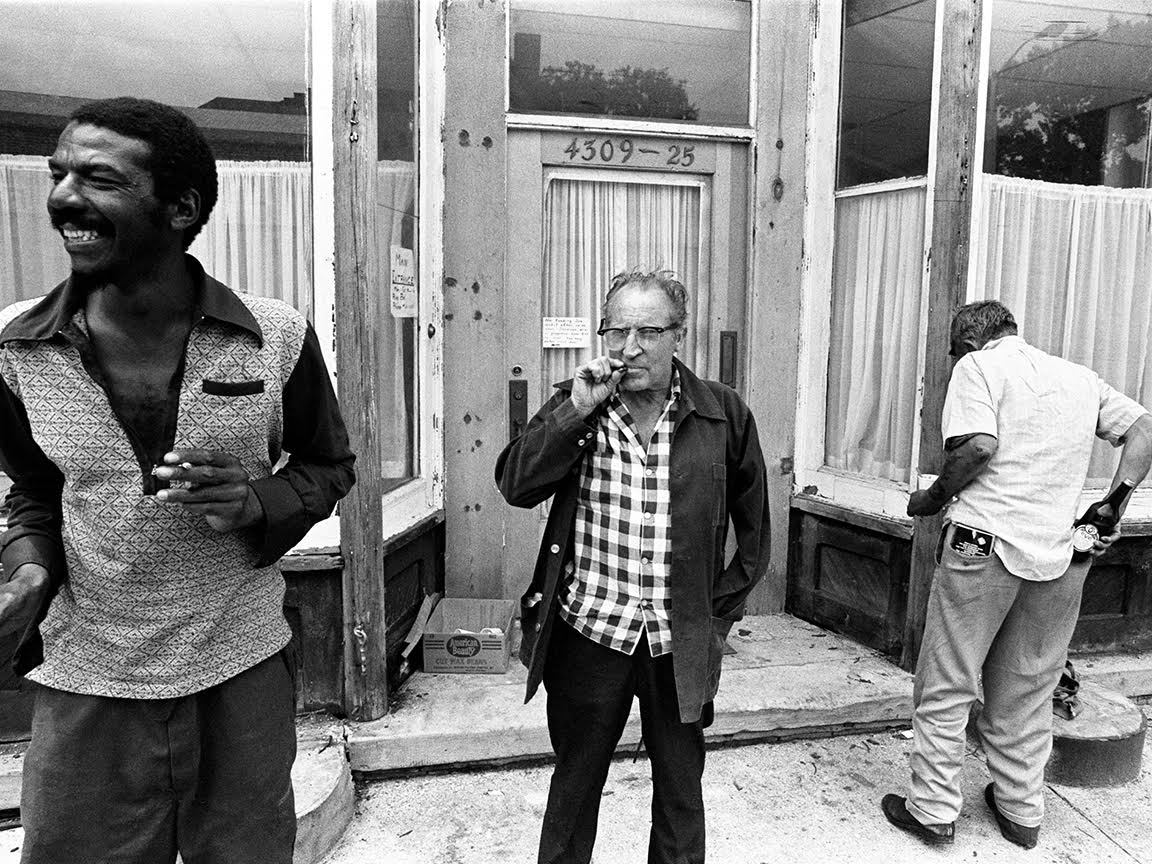

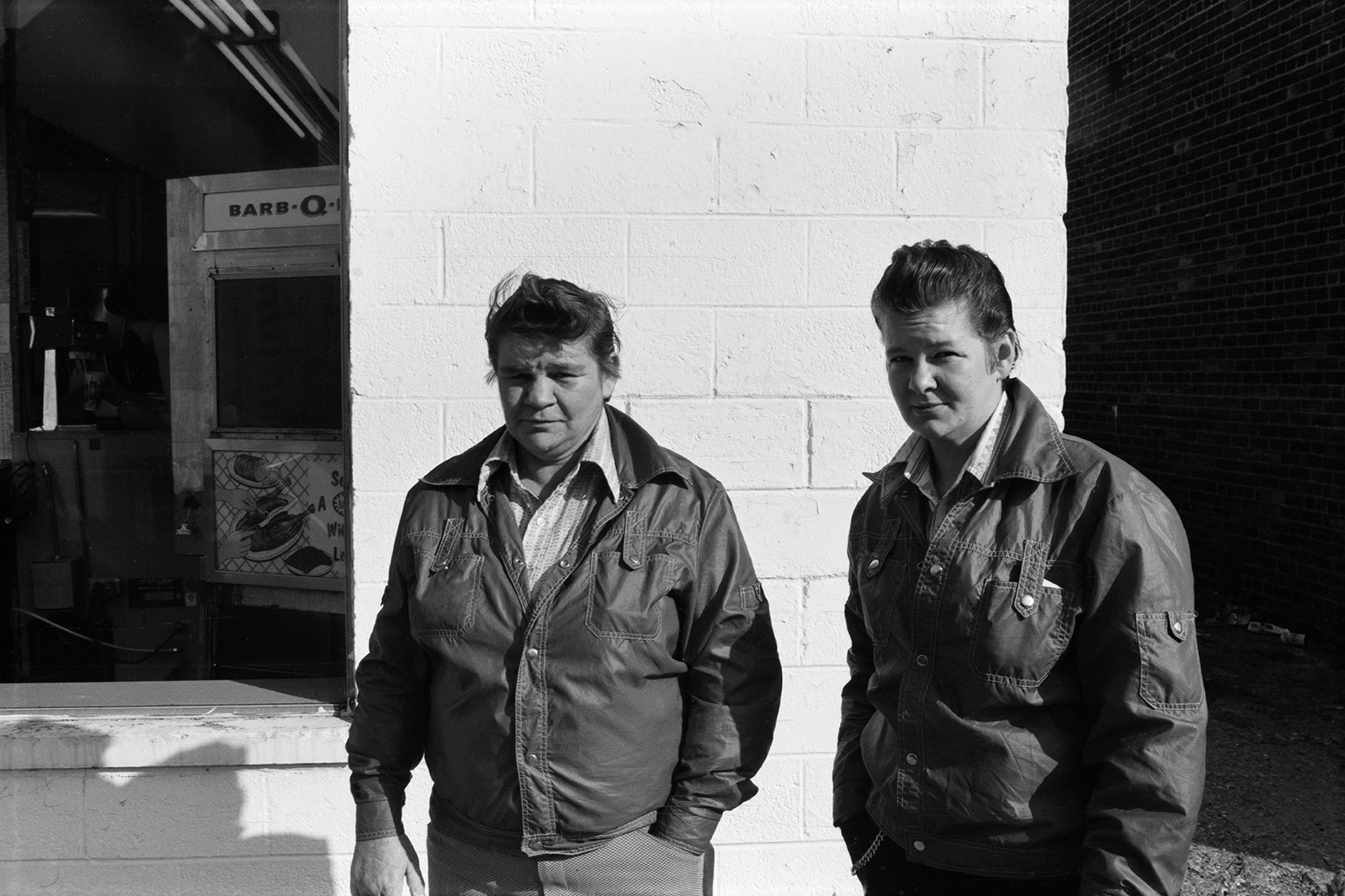

Installation shot, Olga de Amaral: To Weave a Rock, Cranbrook Art Museum, Photo credit for all images except noted: PD Rearick

Amaral first encountered a loom at Cranbrook, even taking one back to Bogotá. Most countries where abstraction was central between the 1940s and late 1970s were immersed in lengthy periods of dictatorships during those decades. Whether despite or because of the political situation, Amaral’s frequent years abroad, always returning to Bogotá, heralded an international career. After initial training in architectural drafting at the Colegio Mayor de Cundinamarca in Bogotá before coming to the U.S. to briefly study English at Columbia University in New York, she transferred to Cranbrook in 1954. During her two years in Michigan, she accomplished the most conspicuous of her transformations as a non-degree seeking student trained by the Finnish-American textile designer Marianne Strengell. Back in the 1940s, artists such as Strengell and Anni Albers at Black Mountain College began to pave the way for a more experimental approach to weaving, opening it up to integrating concerns from the “other” arts of painting and sculpture.

Amaral’s iconic Carretón negre (Black Clover), 1973, reminding us of the sculptural work of Eva Hesse, is displayed prominently as a signature work to be seen immediately upon entry to the exhibition. As it sits on a low white pedestal, supported by a hook, the bulbous knot exudes a tremendous sense of weight. This sculpture is indicative of how in the wake of process-oriented soft sculpture many artists chose to make visible the fact that material behavior in space controls shape. It was appealing that this occurs beyond the immediate control of the artist as a force of nature.

A pictorial play with light and air as forces of transparency in the first tapestries gave way in the 1970s to a radical pursuit of free-standing and free-hanging objects suspended from the ceiling.

Installation shot, Olga de Amaral: To Weave a Rock, Cranbrook Art Museum

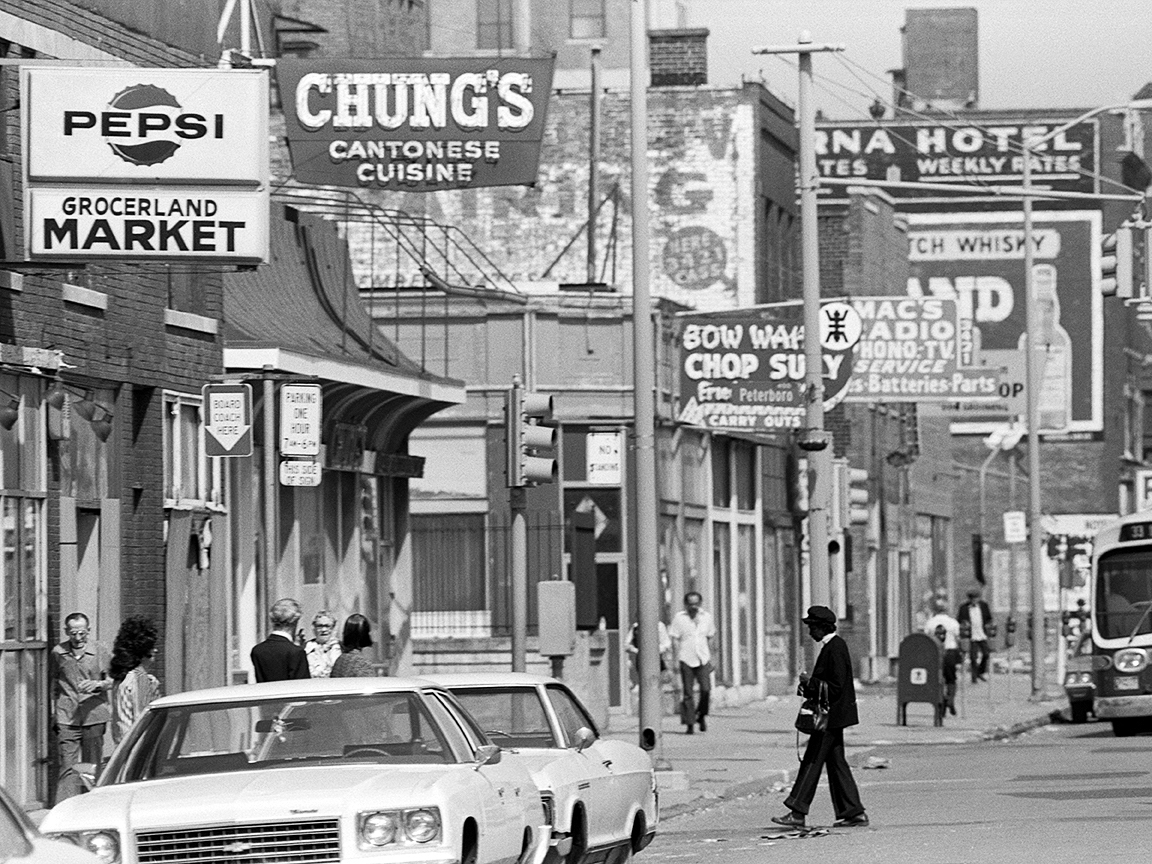

The weavings gain an unprecedented degree of volume in space driven by a sculptural monumentality that explores weight, mass, and gravity as form-giving forces. As a direct response to the developments of Minimalism and Postminimalism when artists became attentive to the architectural context, the behavior of the art material, and the bodily experience of the viewer in space as a mobile entity, fiber art as an independent art form was born in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and Amaral emerges on the forefront of it with the Muro tejidos (Woven Grid Walls.)

Made from wool strings and horsehair braided together, Muro tejido, 1972 (the second work from the left in installation shot 2), rejects the rigidity of the right angle that dominated the loom-based tapestries from the mid-1960s. As weighty and sagging dividers of space, these “physical structures” from the 1970s break with the order of the grid, often omitting the horizontal line of the weft in large sections in an emphasis on materiality as a force of expression. This is accompanied by hand-tying and wrapping increasingly tactile materials of coarse horsehair, broad straps of linen, and even bands of plastic directly into the constructions. Secondary to concerns with shape and volume, color in this period is somewhat subdued to greys and browns and bound to a traditional waving process of dying the thread before the weave. Increasingly, throughout the 1990s and 2000s, the color becomes a vital force when fabric works are made entirely off the loom.

Installation shot, Olga de Amaral: To Weave a Rock, Cranbrook Art Museum

This stellar show of about fifty works shines a light on those terrific leaps into space and color by Amaral, so that viewers can study the formal changes in a mostly chronologically organized lineup from 1965 to 2017. The five curatorial themes of “Rebel Warp,” “Radical Materialism,” “Alchemy,” “Space Odyssey,” and “The Line” cut through an artistic oeuvre characterized by series that often carry associative references to the landscape of Antioquia dominated by the Andes Mountains and prehistoric Colombia.

Of special note in this regard is a series of luminous golden plaques begun in 1996, the Estelas; the title is the artist’s creative composite of the Spanish words for star and fabric. Tightly grouped together in a black niche, about a dozen items hang from the ceiling on transparent nylon wires. The crusted surfaces shimmer brilliantly in the light, strongly enhanced by their contrast to the surrounding black wall paint.

Installation shot, Estela Grouping, 2007, linen, gesso, and gold leaf, Olga de Amaral: To Weave a Rock, Cranbrook Art Museum, Photo credit: Nadja Rottner

Ancient cultic monuments, stone tablets, or gravestones come to mind that brings ideas of ritual, commemoration, memory, and the passing of time on a cosmological scale to the fore. All the while, the double-side sculptures items float precariously in space with changing impressions of light and color lending a quality of impermanence and fragility to the Estelas that seems contradictory. Color is no longer the result of a fabric dye but added onto a linen ground with a tool, stabilized by gesso in the manner of a painter. Words such as off-stretcher painting, free-hanging sculpture, or off-loom weavings characterize her objects as Amaral continues to abandon the fundamental concept of weaving—the opposition between the warp and the weft—entirely in the most recent decades of her practice.

One such example hangs to the left of the Estelas. Suspended from the ceiling and about two feet away from the wall, a black and dark green curtain-like item leaves a strong but unstable and fluctuating cast shadow with a wave pattern behind it.

Olga de Amaral, Entorno Quieto 5 (Quiet Environment 5), 1993, Wool and horsehair, 86 ½ x 86 ½, Courtesy: Case de Amaral.

In Etorno Quieto 5 (Quiet Environment 5), 1993, we encounter an alternative conception of surface and support from the Estelas. Two superimposed planes of differently colored fabric celebrate the freedom of the vertical line from its horizontal imprisonment, creating a wave like vibration of shape reminiscent of the illusionism of optical art when an artwork sets in place shape and color oscillations subject to the viewer’s eye-brain response. Then there is the fact that the fabric threads literally move in infinite ways by circulations of air.

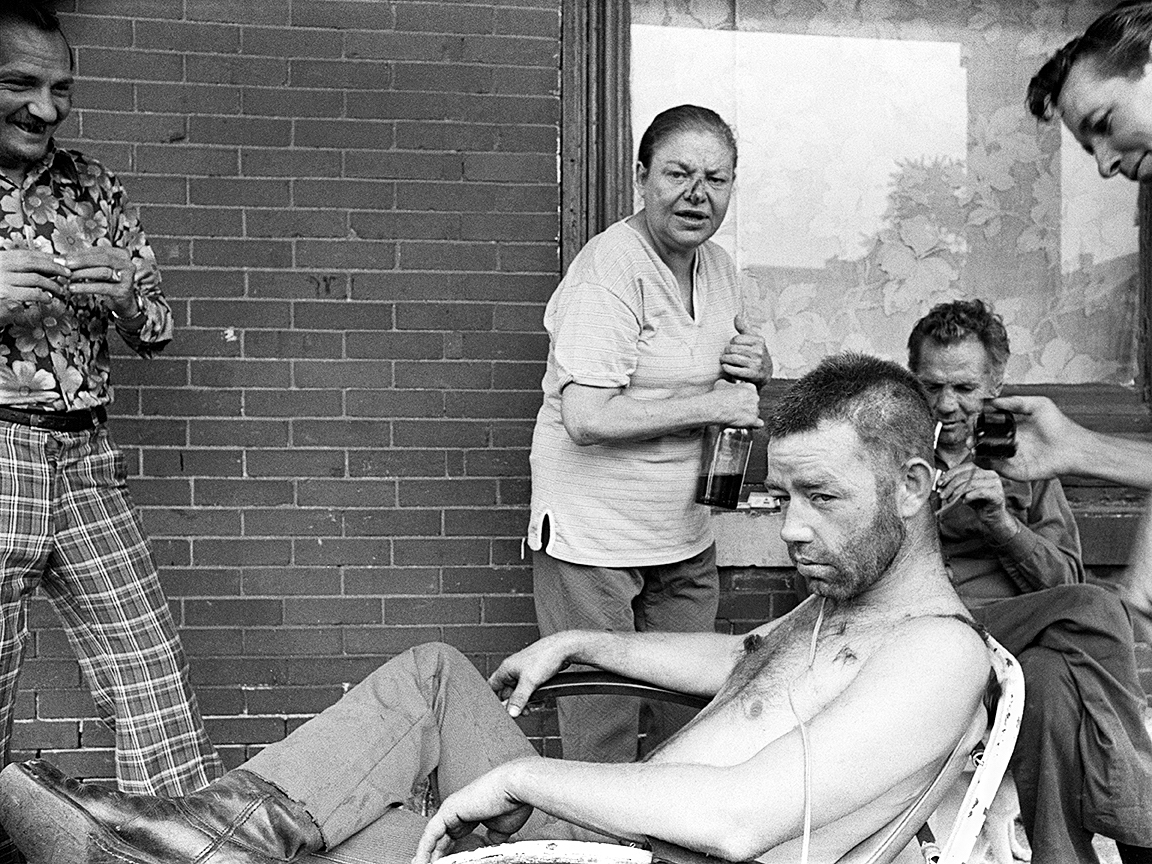

Extending this push toward opticality into a room-spanning environment, the viewer encounters the impressive installation of the Brumas (Mists), 2013, made from acrylic, gesso, and cotton on wood, toward the end of the gallery. Hung off four black rectangular panels (each about 75 x 35 inches in size), myriads of colored threads hang loose. Cut at different lengths, the impression of triangular shapes is only upended when the moving viewer comes in closely.

Installation shot, Olga de Amaral: To Weave a Rock, Cranbrook Art Museum

This work, among others from the last three decades of her practice, is directly inspired by two forms of geometric abstraction, known as Optical (or Op art), a style of abstract art based on patterns and optical illusions, and Kinetic art (objects that have moving parts). Both became popular in Venezuela in the 1950s and 1960s represented by artists such as Carlos Cruz-Diez and Jesús Soto. Their works included small and large-scale abstract sculptures in bright colors and industrial materials that promote the experience of color by the viewer, through his or her own subjectivity, in an individual, emotional and virtual way, changing the way we perceive space, light, and movement.

Behind the Brumas in the last room on the left, three recent tall knots from 2016-2017 are suspended from the ceiling, all the while touching a floor pedestal. Nudo 19, 27, 25 are colored in non-naturalistic turquoise, yellow, and magenta (made from linen, gesso, acrylic.) They stand in front of two vibrant tapestries titled Lienzo en dos colores (Canvas in Two Colors), featuring a blue and green color combination and one in red and magenta that matches the knots. These works recall an artist’s statement from the video, namely that mixing colors in fabric art is like painting, except that paint is replaced by died threads that are interwoven, be it on a machine or by hand.

The show brings out beautifully how the work as a whole oscillates semantically, formally, and procedurally around artistic and intellectual concepts of opposition such as opticality versus gravity, the industrial and the indigenous, the hand and the machine. Air, movement, gravity, and water evoke ideas of natural change and impermanence. They stand in a productive dialogue with concepts such as universality, the cosmological, and the monumental. It is those tensions, among others, that animate the work from within.