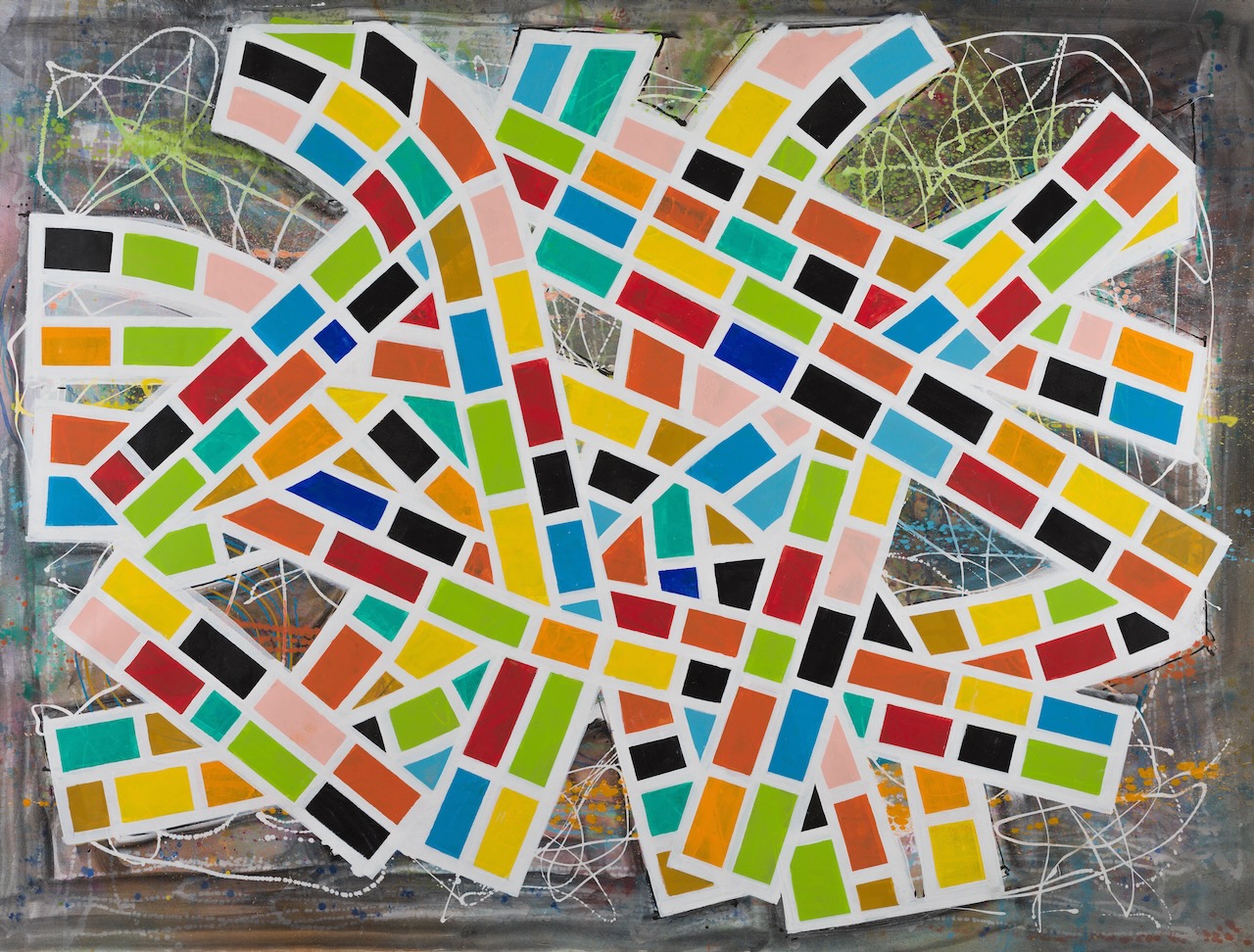

Installation view of Robert Sestok: Space and Time at Detroit’s Simone DeSousa Gallery through Dec. 17.

Many Detroiters may associate Cass Corridor veteran Robert Sestok most with his towering steel assemblages, simultaneously daunting and mesmerizing, found around downtown and Midtown as well as at his City Sculpture Park. But with Robert Sestok: Space and Time at the Simone DeSousa Gallery, the 2017 Kresge Artist Fellow reminds us that in addition to being a large-form sculptor, he’s also an adroit painter perfectly willing to break form and startle his audience.

Space and Time, up through Dec. 17, speaks to both talents. Your first impression on entering might be one of technicolor roadmaps, given the belts of strongly colored “brick paths” barreling across the three Origins canvases in the first gallery. It’s all a bit hallucinogenic. Picture the Yellow Brick Road on acid and you’re halfway there. Contributing to the visual drama is that these are big pieces – in the neighborhood of 11 feet by nine feet – and our view is seemingly from high above, as if peering down on three incredibly complex, colorful LA freeway interchanges superimposed on gray backgrounds covered with thin, dreamy dribblings of paint.

Robert Sestok, Origin #3, 2022, Acrylic on canvas, 108 x 144 x 2 inches. (Courtesy Simone DeSousa Gallery.)

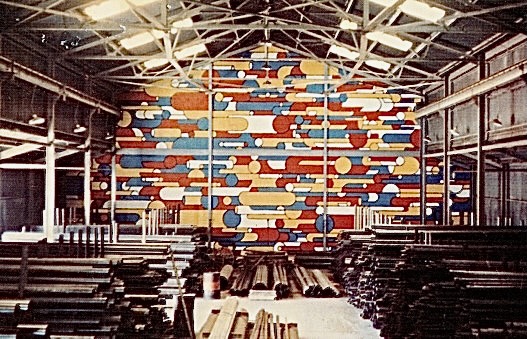

“This work reaches back to my early murals at the Duffy Company,” Sestok said, referring to the interior and exterior murals he created in 1971 at the behest of James Duffy, the collector and art patron who owned the warehouse at West Jefferson and Junction that housed his family’s steel-pipe business. (Duffy would later bequeath his outstanding Cass Corridor collection to Wayne State University.)

“When you walked in,” Sestok said of the warehouse, now leveled for the Gordy Howe International Bridge to Canada, “you’d see this huge pile of heavy steel pipes — and down the wall you’d see a mural of the pipes floating in space.”

The floating pipes were painted on concrete-block walls, and Sestok used the horizontal grout lines as a sort of hard-edged framing device for his lyrical circles. And there you can see the genesis, perhaps, of the bold linear stripes in Origins, underlining the artist’s habit of circling back to work made decades ago, pulling out old ideas and making them new again.

“I kind of shocked myself,” Sestok said. “I didn’t realize at first I was repeating something I’d done a long time ago. It just came out of me.”

Interior of the former Edward W. Duffy Co. steel-pipe warehouse near Fort Wayne, with Robert Sestok’s 1971 mural on the far wall. (Courtesy of the artist)

Sestok, who grew up in Birmingham, got his very first Detroit studio in 1967 with Gordon Newton in the Old Convention Hall near Wayne State University, a building that also housed other Corridor artists like John Egner, Michael Luchs, Brenda Goodman and Jim Chatelain. For his part, Sestok quickly developed a reputation for productivity – or, as critic Dennis A. Nawrocki’s put it in Essay’d, “the prime protagonist of the indefatigable do-it-yourself Detroit work ethic.”

(A good example of that ethic is Sestok’s one-man City Sculpture Park with about 30 works that went up in 2015 at the John Lodge Freeway Service Drive North and Alexandrine in Detroit, and came down in 2020. It was a striking gift to the city; those who’ve mourned its disappearance will be happy to learn that it’s been relocated a couple miles away to 3573 Farnsworth, just west of Mt. Elliott.)

Playing the role of midwife to the Cass Corridor movement was the formerly depressed neighborhood along Cass Avenue south of Wayne State – the sort of urban streetscape in the Sixties and Seventies where nervous suburbanites punched the gas pedal. In those years, the Corridor attracted dozens of young, artistic rebels with a collective attraction towards the gritty and the raw, and a bent for exploiting the city’s treasure trove of industrial detritus.

In spotlighting the work of this rowdy cohort, the movement’s principal exhibition space – the Willis Gallery (where Avalon International Breads is today) — drew serious attention from Sam Wagstaff, curator of contemporary art at the Detroit Institute of Arts, as well as coastal art elites, who started paying attention to the Motor City for the first time in decades. (Indeed, there are some, Sestok included, who argue the Corridor represents the only actual artistic movement the city’s ever generated.)

“The art was kind of fast and furious,” Sestok told The Detroit News in an interview 10 years ago, “with people in competition with each other to get their work in the gallery and have a show. It was an exciting time.”

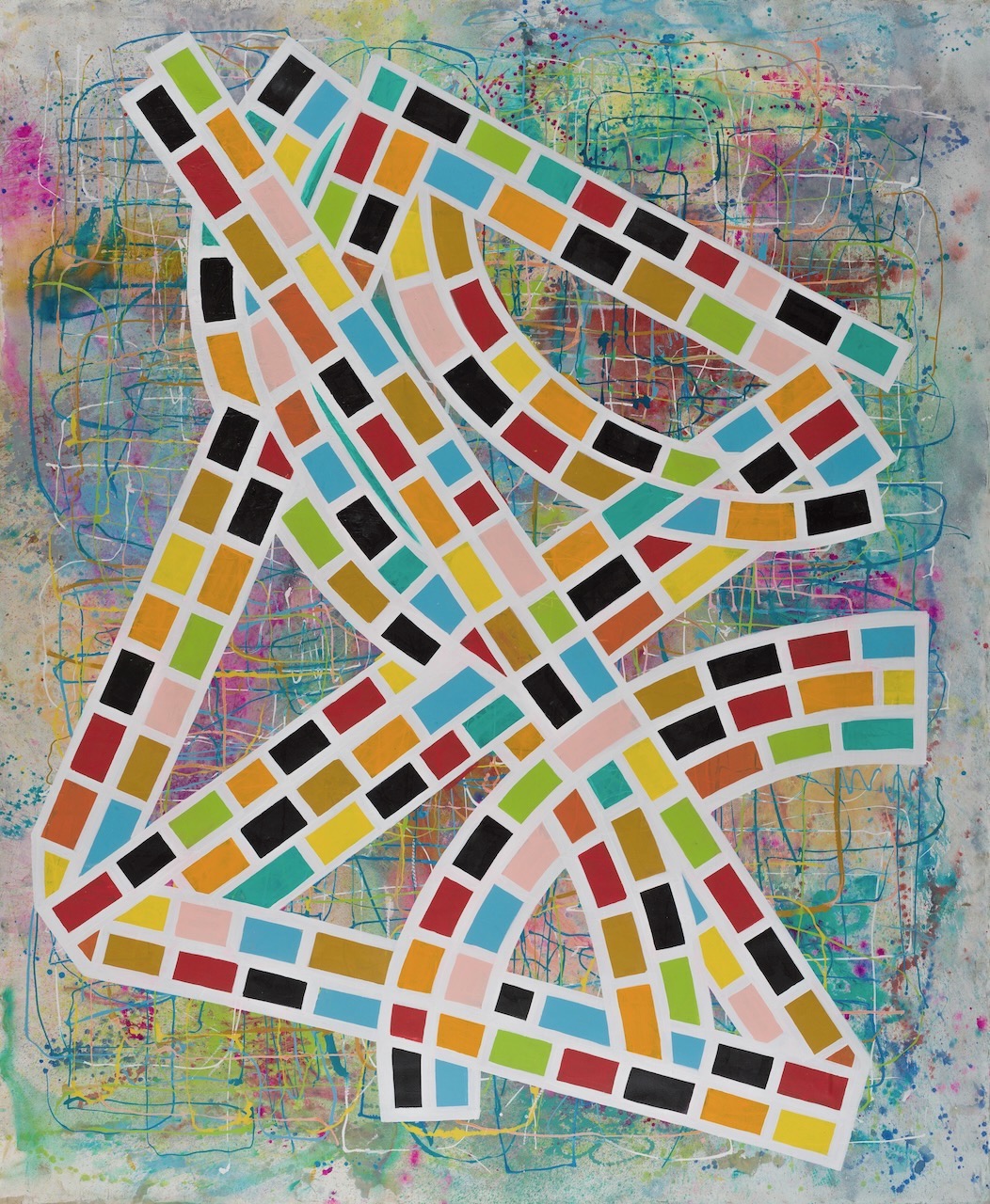

Robert Sestok, Origin #1, 2022 Acrylic on canvas 132 x 111 x 2 inches. (Courtesy Simone DeSousa Gallery)

“Fast and furious” isn’t a bad description for Origins Nos. 1-3, cited above, all of which are three-step constructions. First Sestok poured and pushed (in some cases with a leaf-blower) thick gray paint to form the substructure, with a second layer of colorful, whimsical dribblings enlivening the surface. On top of that composition, and blotting out most of it, he laid down the severe, multicolored geometric pathways.

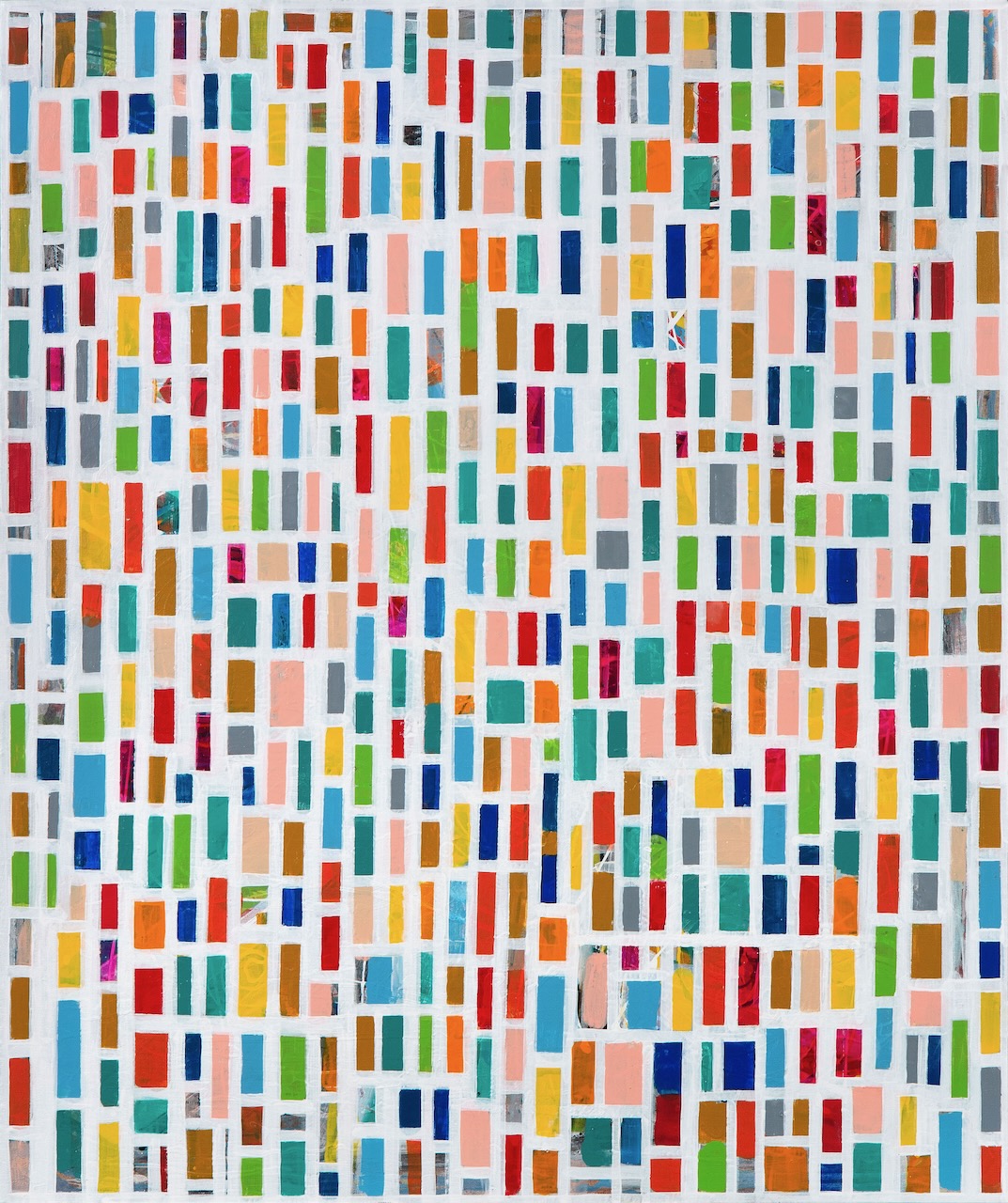

Intriguingly, the simply titled Origin in the gallery’s back room inverts this hierarchy. Here the geometric checkerboard is overlaid with thin, circular vortices and a drizzled white line that meanders, taking its time, all across the canvas. In some ways it’d be interesting to see Origin installed between two of the front-room pieces, rather than segregating it. The contrast in aesthetics, and the clear inversion in design, would be bracing.

Robert Sestok, Origin, 2022 Acrylic on canvas, 63 x 53 x 2 inches. (Courtesy Simone DeSousa Gallery)

Completing the show are several works, somewhat smaller than the exclamation points in the first gallery, that also lean heavily on geometry, but in a completely different fashion. Origins Nos. 4-6 feature something like gridworks of colored squares and rectangles – sharp and exact, as if cut into the white backgrounds with an X-Acto knife.

They are, it must be said, in many ways quite beautiful. “Yeah,” said Sestok, “if you can get away from the wallpaper idea.”

Robert Sestok, Origin #6, 2022, Acrylic on canvas, 63 x 53 x 2 inches. (Courtesy Simone DeSousa Gallery)

Robert Sestok: Space and Time will be up through Dec. 17 at Detroit’s Simone DeSousa Gallery.