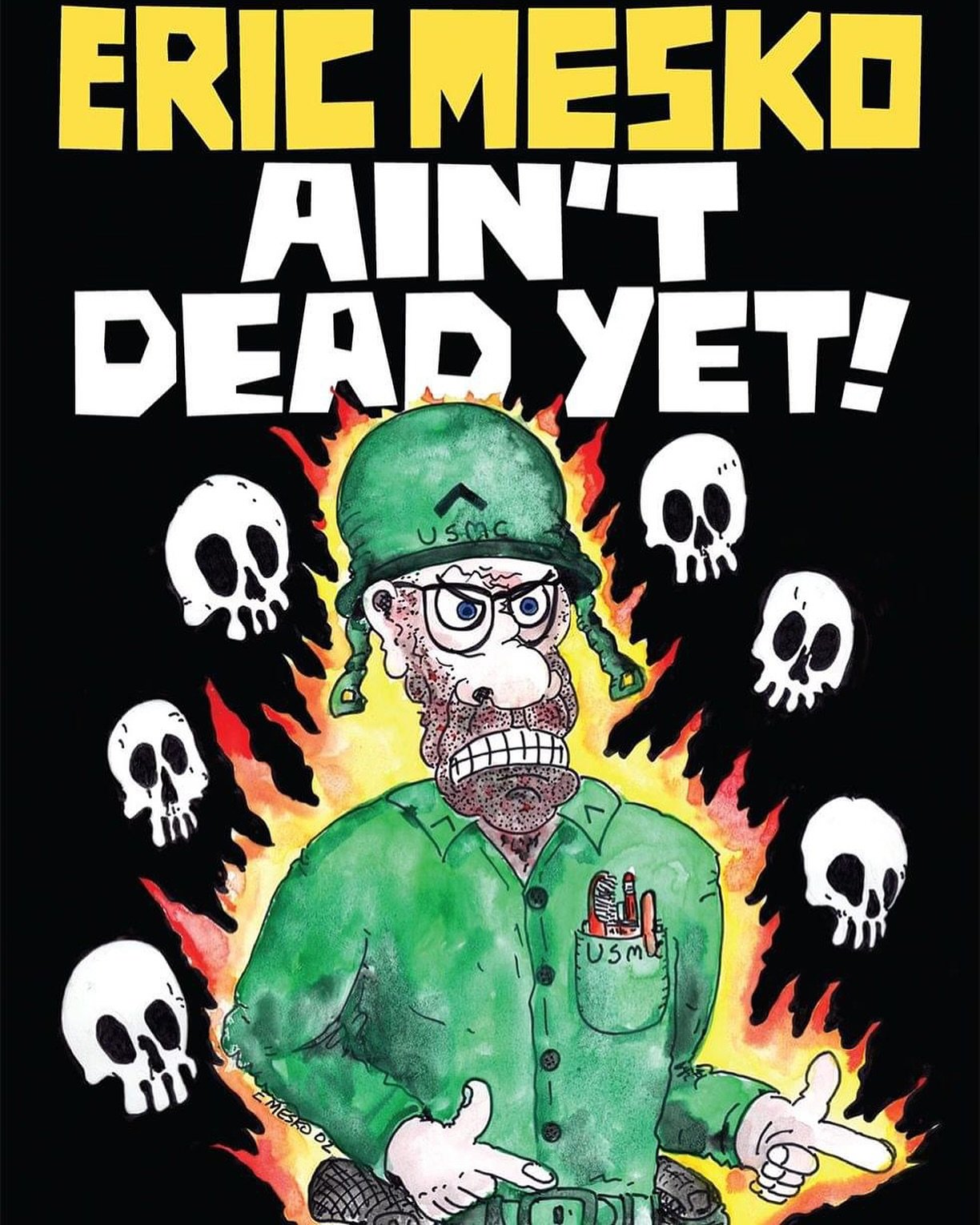

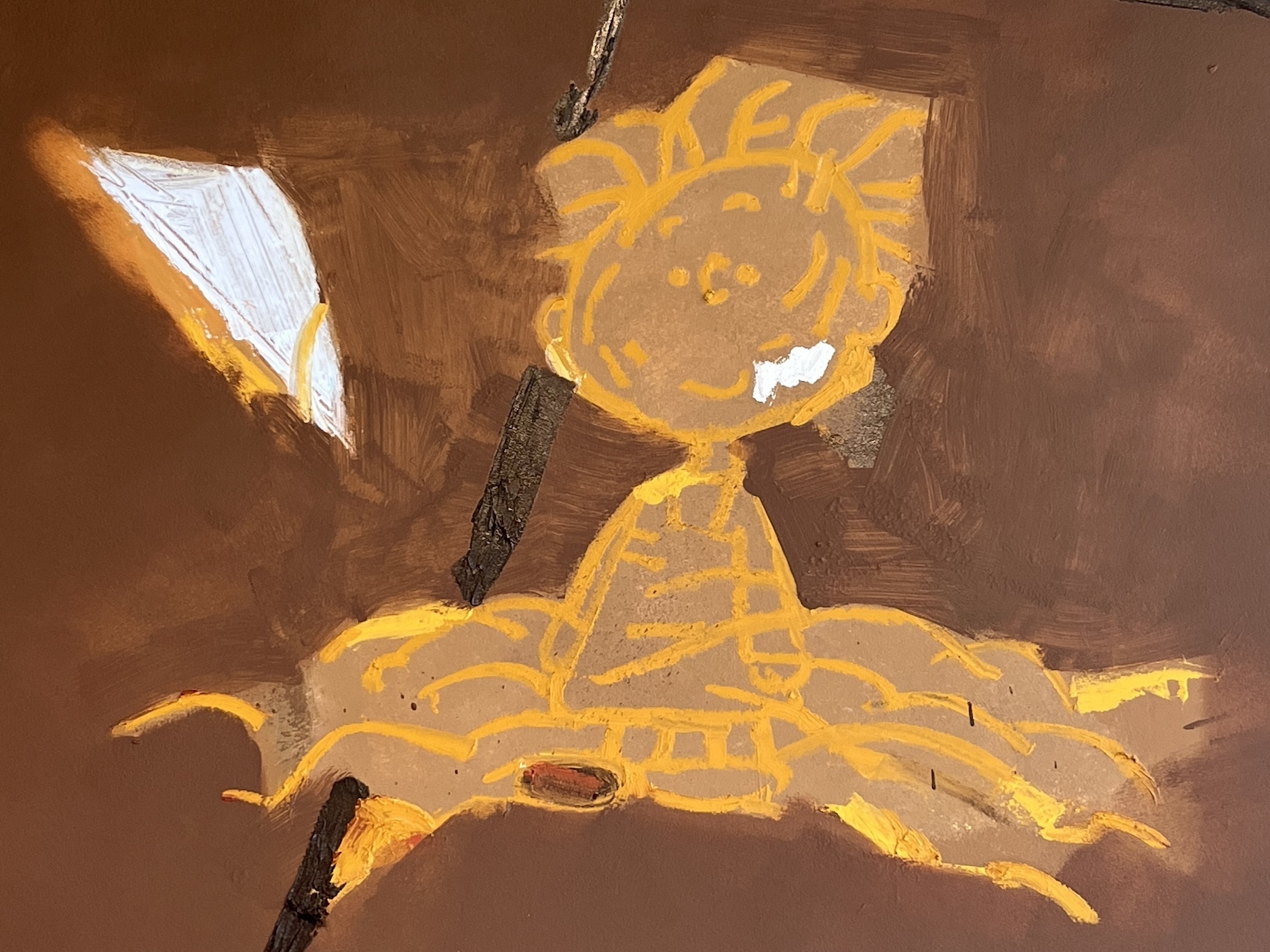

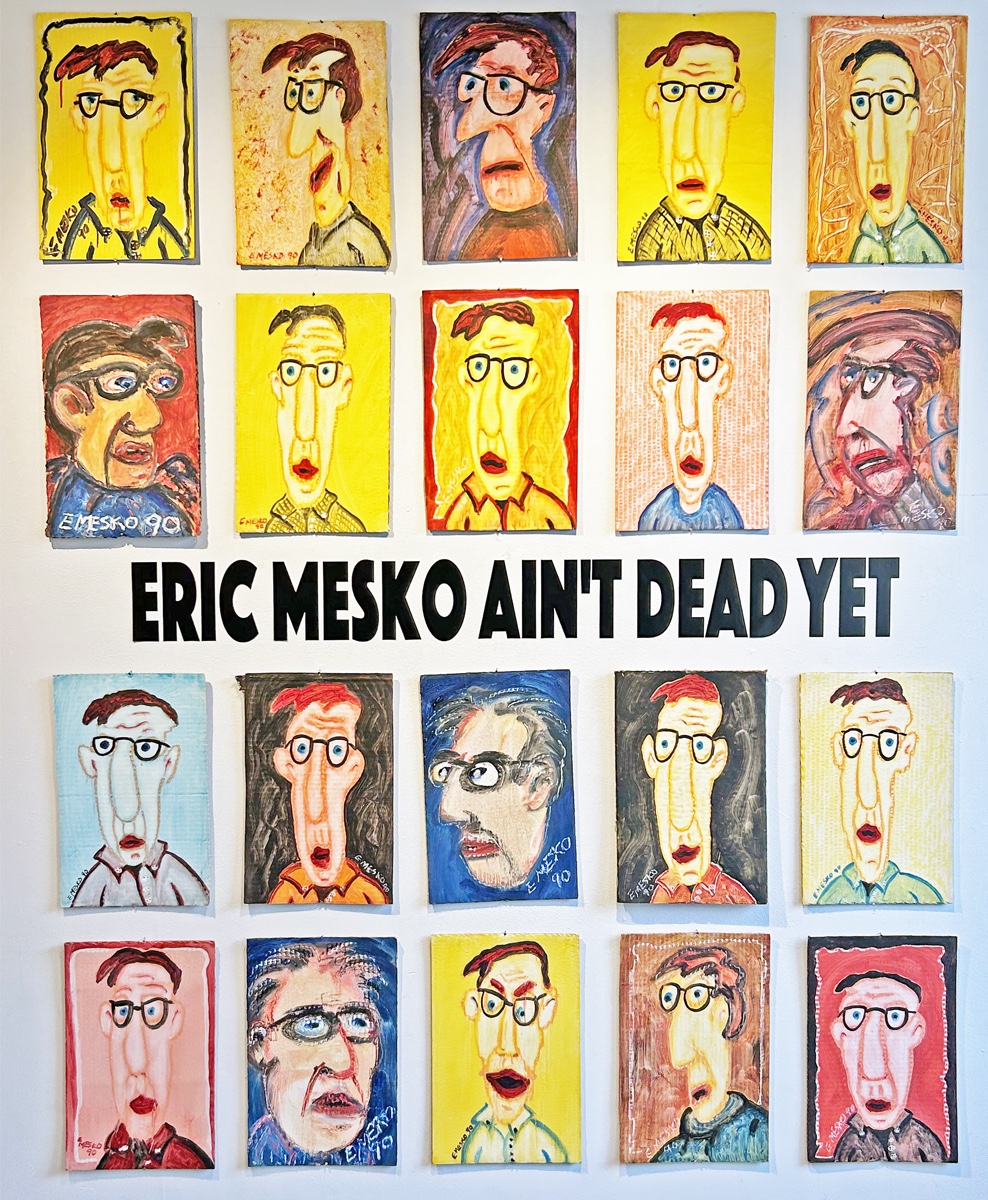

Eric Mesko, Self Portraits, 1990, 10” x 15”, acrylic on cardboard.

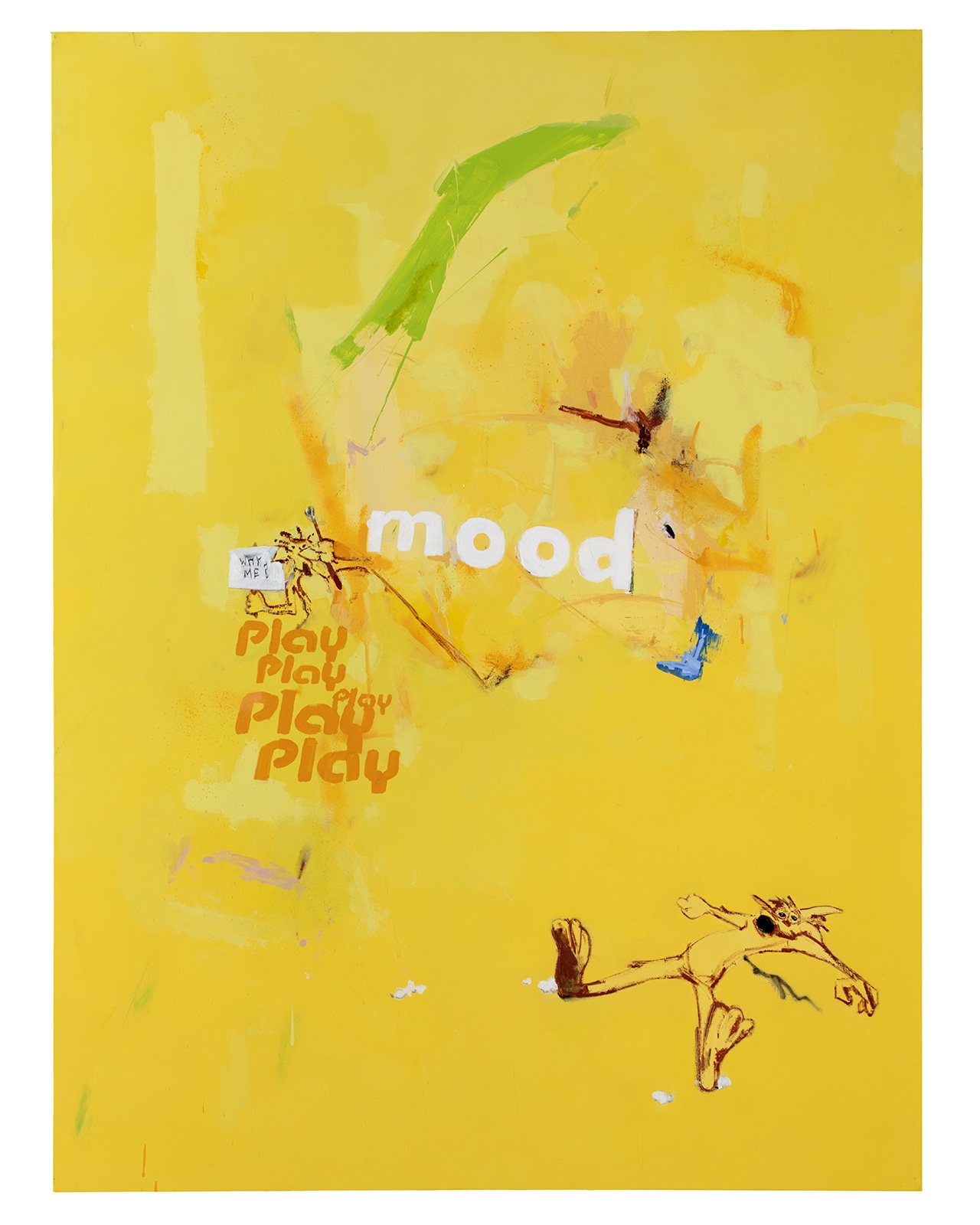

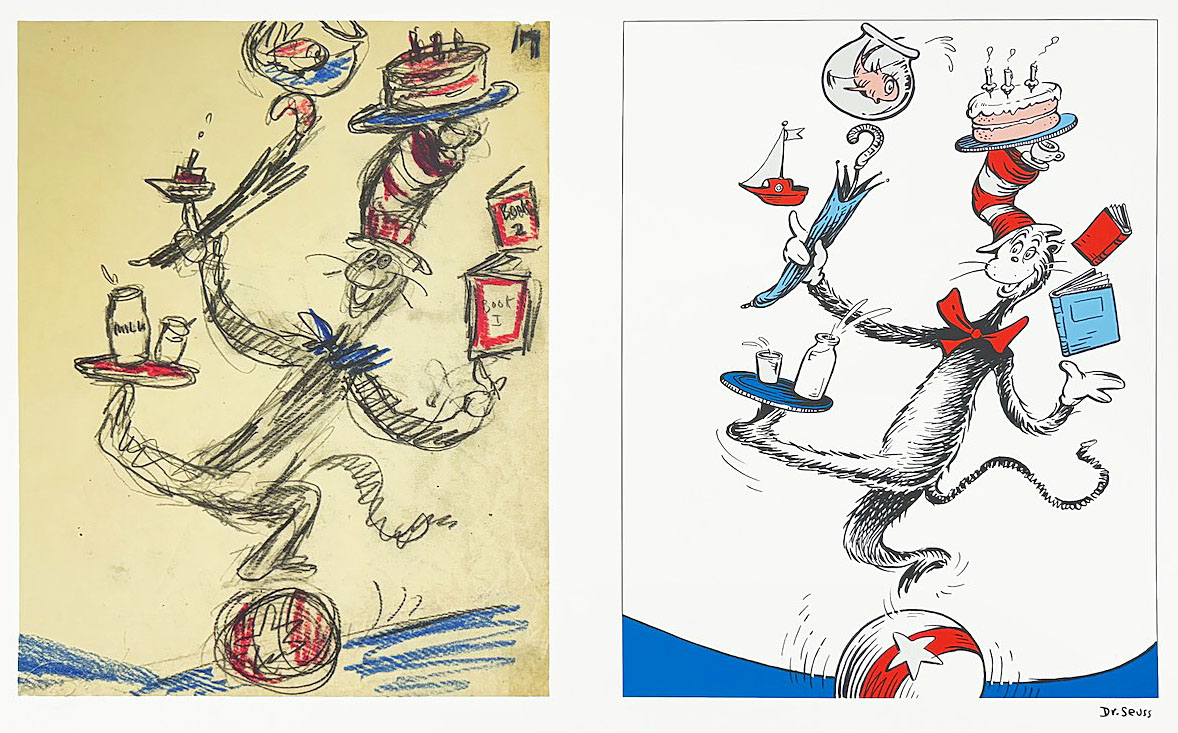

Disorientation, exhilaration, and amusement are feelings gallery visitors will experience upon walking into Hatch Gallery right now, where work by Detroit artist Eric Mesko is on display. “Eric Mesko Ain’t Dead Yet” is a retrospective of sorts, though not a complete one. Christopher Schneider and Sean Bieri, who curated the exhibition, have selected a generous slice of Mesko’s 50-year output from a rich trove of art and artifacts in the artist’s Ferndale house and studio. Most of the work is from the 1990s and gives a taste, at least, of the preoccupations and style of expression of this artist and activist, whose work was described by Rebecca Mazzei of the Detroit Metro Times in 2005 as “extreme expressionism.”

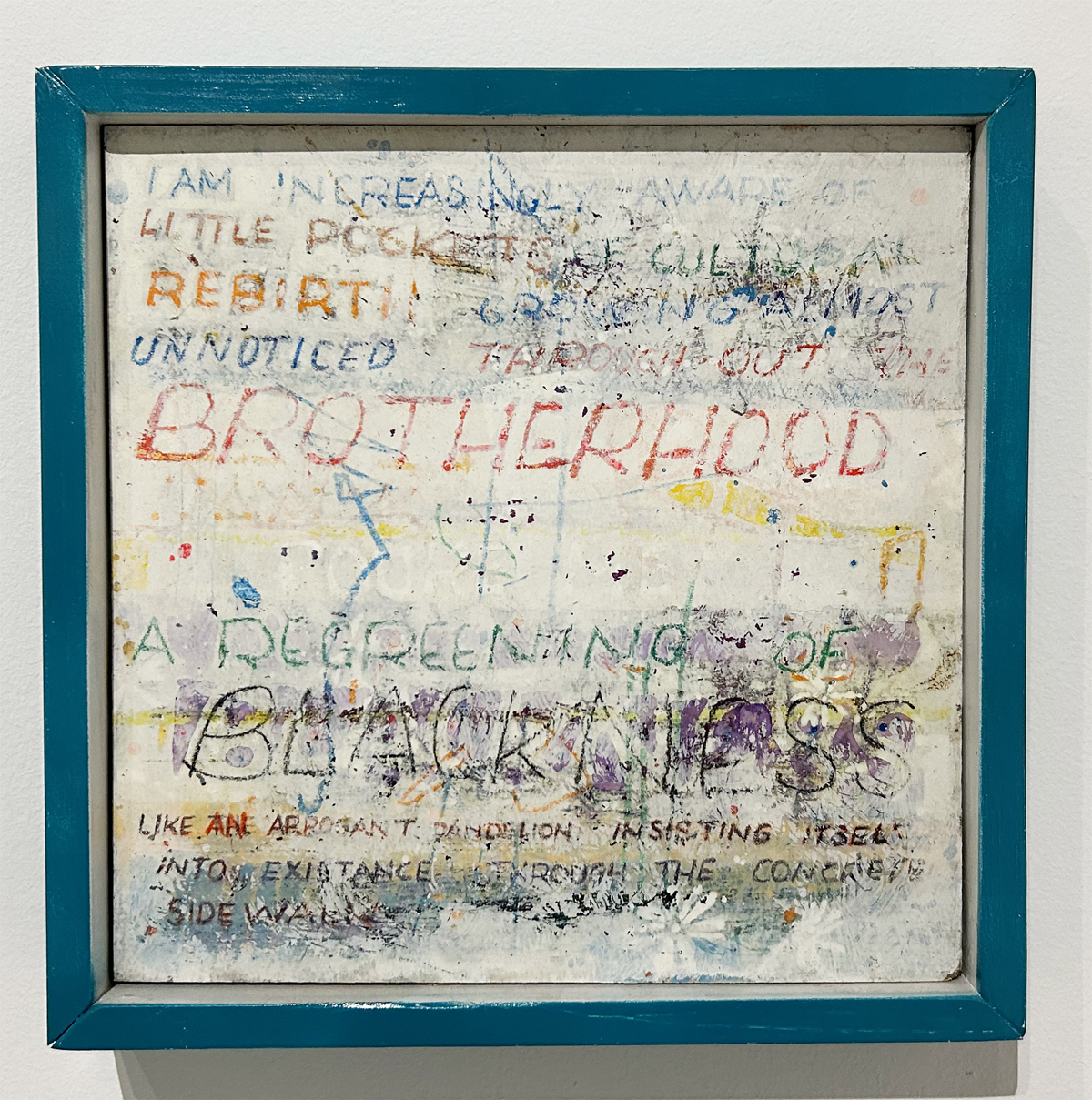

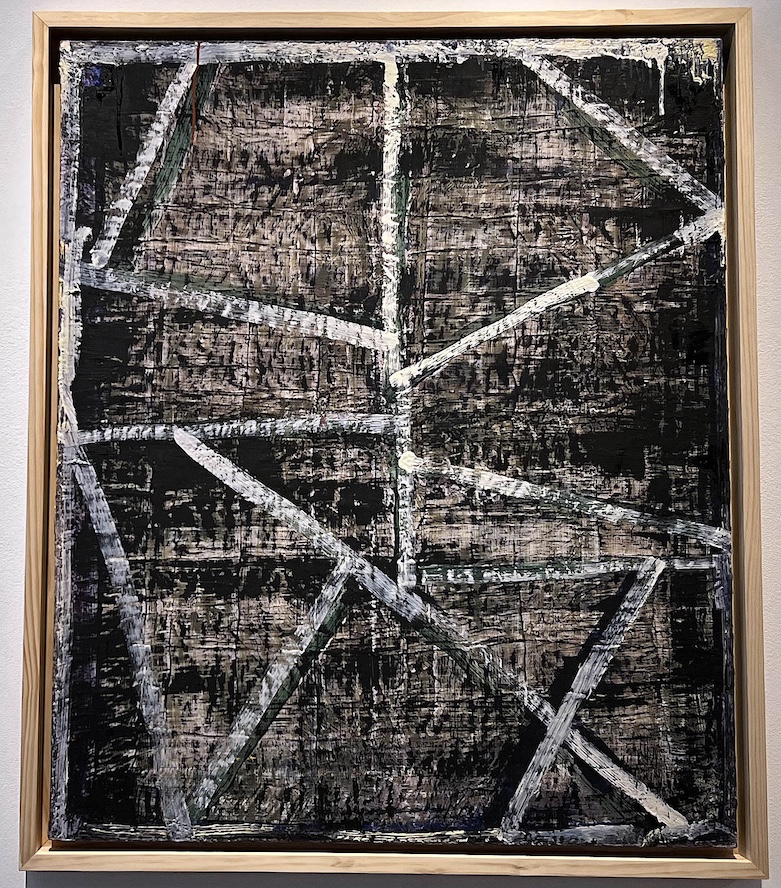

Eric Mesko, Oil Wars, 1990, 24” x 36” acrylic and oil stick on board.

Mesko’s childhood in the 1940s, as the son of a lieutenant colonel in the Marines, gave him a unique position from which to view the place of America on the world stage, for good or ill. His frequent moves from military base to base, both in the U.S. and worldwide, gave him a global perspective on both his own American identity and world cultures. Though an inveterate natural draftsman from an early age, Mesko didn’t take an art class until his last year in high school. He enlisted in the Marines after graduation and served three years, until 1967, and only began to study art seriously in the late 1980s when he earned both a B.F.A and an M.F.A. from Wayne State University.

Eric Mesko, installation, Exhibition poster (2024), small Uvalde Kid, (n.d.) wood, found objects.

In a 2002 essay on Mesko, Dick Goody, Director of the Oakland University Art Gallery, described his work as “more steeped in the traditions of cartoon comics than twentieth-century art,” a statement that is both accurate and incomplete. While many of the works on paper undeniably reference the visual tropes of comic books, Mesko’s sculptures equally suggest his deep familiarity with Chicago Imagists like H.C. Westermann and with post-World War II folk art traditions such as hand-painted signs and improvised cultural artifacts. He also claims familiarity with, and appreciation for, American regionalists like Thomas Hart Benton, and even names Jackson Pollock and El Lissitzky as influences. In the end it is impossible, and possibly pointless, to describe Mesko as either an insider or an outsider. His work, while encompassing all these influences, has coalesced into its own unique perspective; he is both insider and outsider, a sophisticated thinker making work within a primitivist visual idiom.

Eric Mesko, Batter, (n,d) wood assemblage, found objects,

Eric Mesko, Uvalde Kid, 1998, 30” x 42” x 17” wood, found objects.

Many of the recurring images in the exhibition circle around the identity and meaning of American masculinity. G.I.’s., baseball players and cowboys figure prominently In Mesko’s personal iconography as symbols of American values past and present. The Uvalde Kid, named after one of many childhood homes of the artist, is one of the larger assemblages in the exhibition. Astride his horse and brandishing a pistol, he is a reminder that frontier violence is an enduring feature of the American psyche, recently made immediate by the mass shootings in Uvalde, Texas. The G.I.’s in Mesko’s pictures, too, practice sanctioned violence in furtherance of national goals. Yet they seem helpless, cogs in an oil-fueled war machine. His large acrylic and oil stick painting on panel Oil Wars (1990) and the small wooden tank that sits in front of it, are two of several artworks that reference the wars in Iraq and the U.S.’s historically vexed relationship to the oil economy.

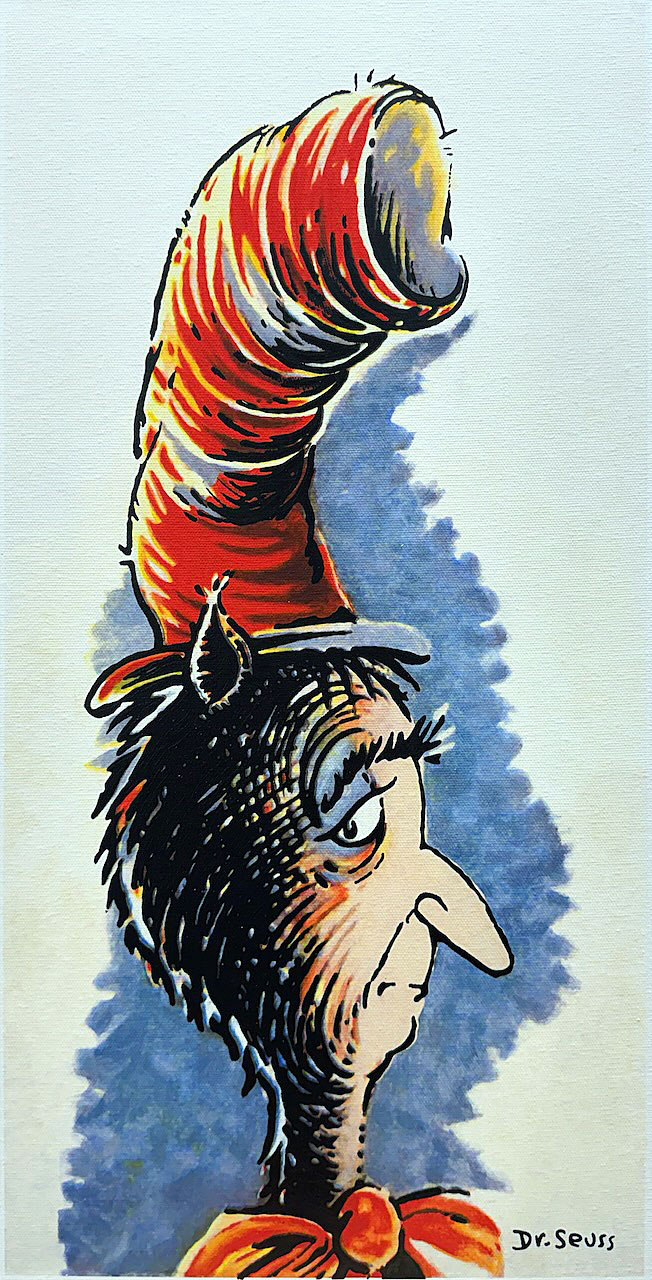

Eric Mesko, Oil Warrior, 1991, 11” x 14,” Ink and watercolor on paper

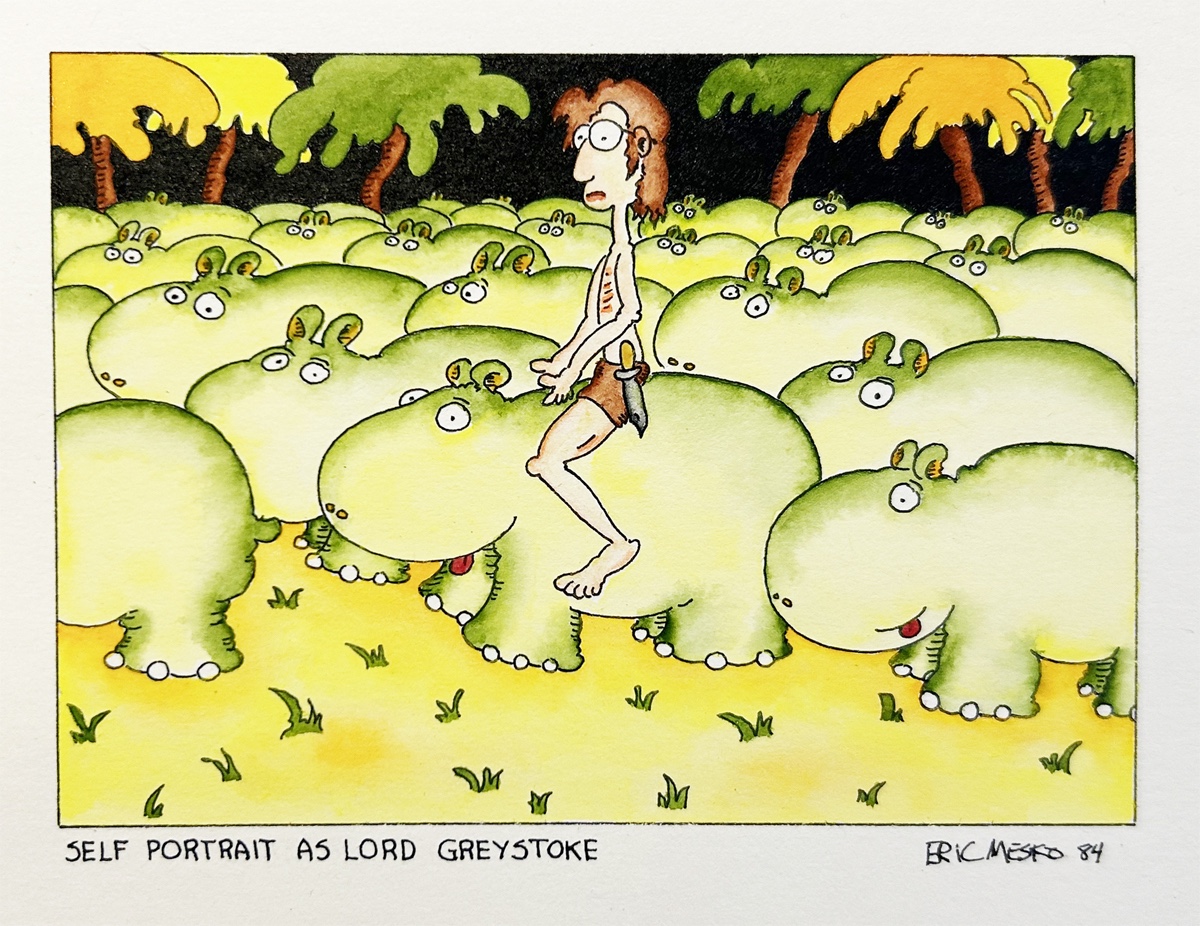

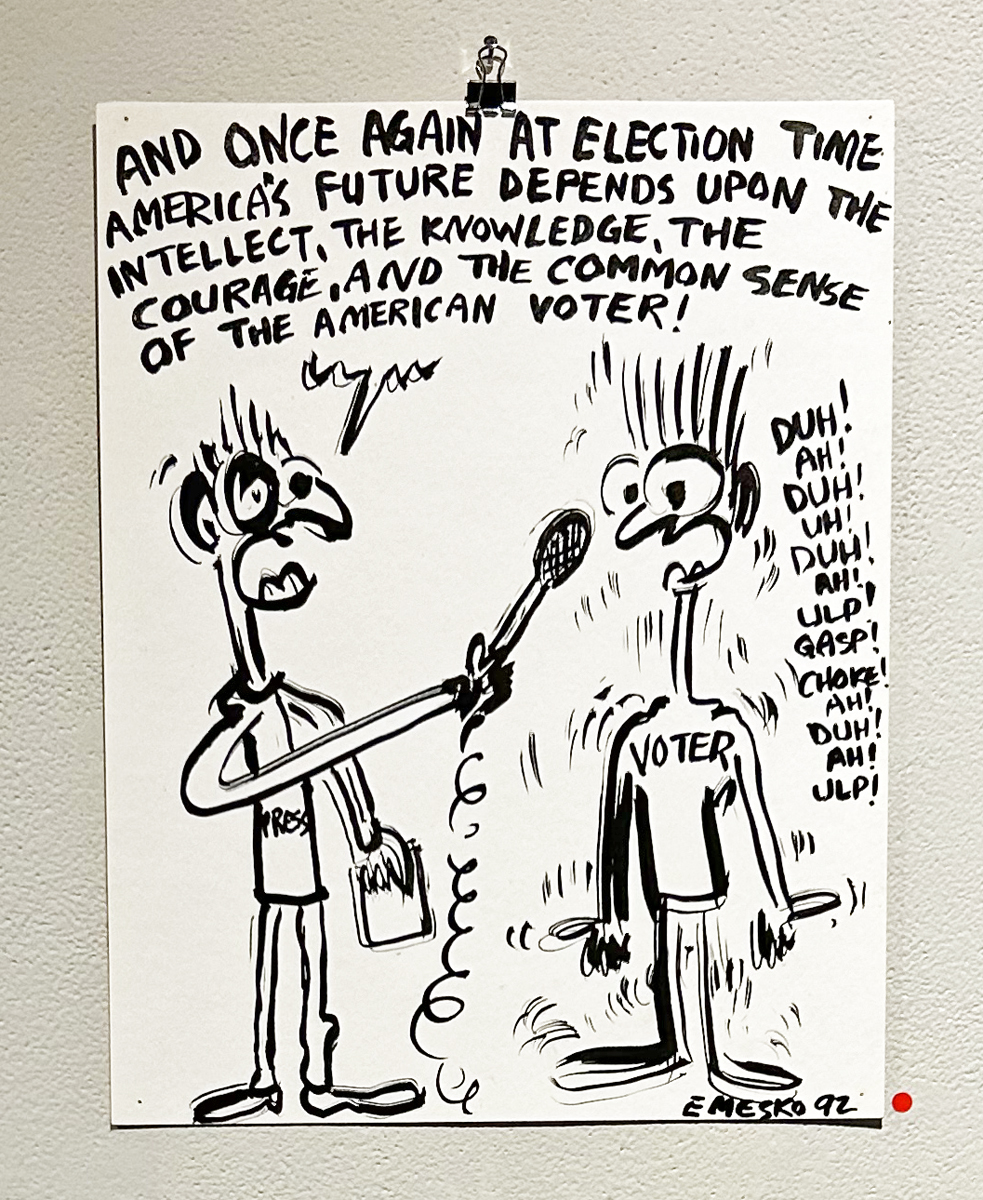

Lest all of this should appear too grim, let it be noted that many of Mesko’s images and artifacts are comic. In Self Portrait as Lord Greystoke, the artist pictures himself as Tarzan, bemused atop a herd of hippos. In another large painting, Mesko portrays the sculptor Tony Smith in a battle for art supremacy, King Kong vs. Godzilla style. Mesko’s pictures can be light-hearted, even silly, although they often make an ironic point, as in his American Voter drawing.

Eric Mesko, Self-Portrait as Lord Greystoke, 1984., 11” x 14,” ink and watercolor on paper.

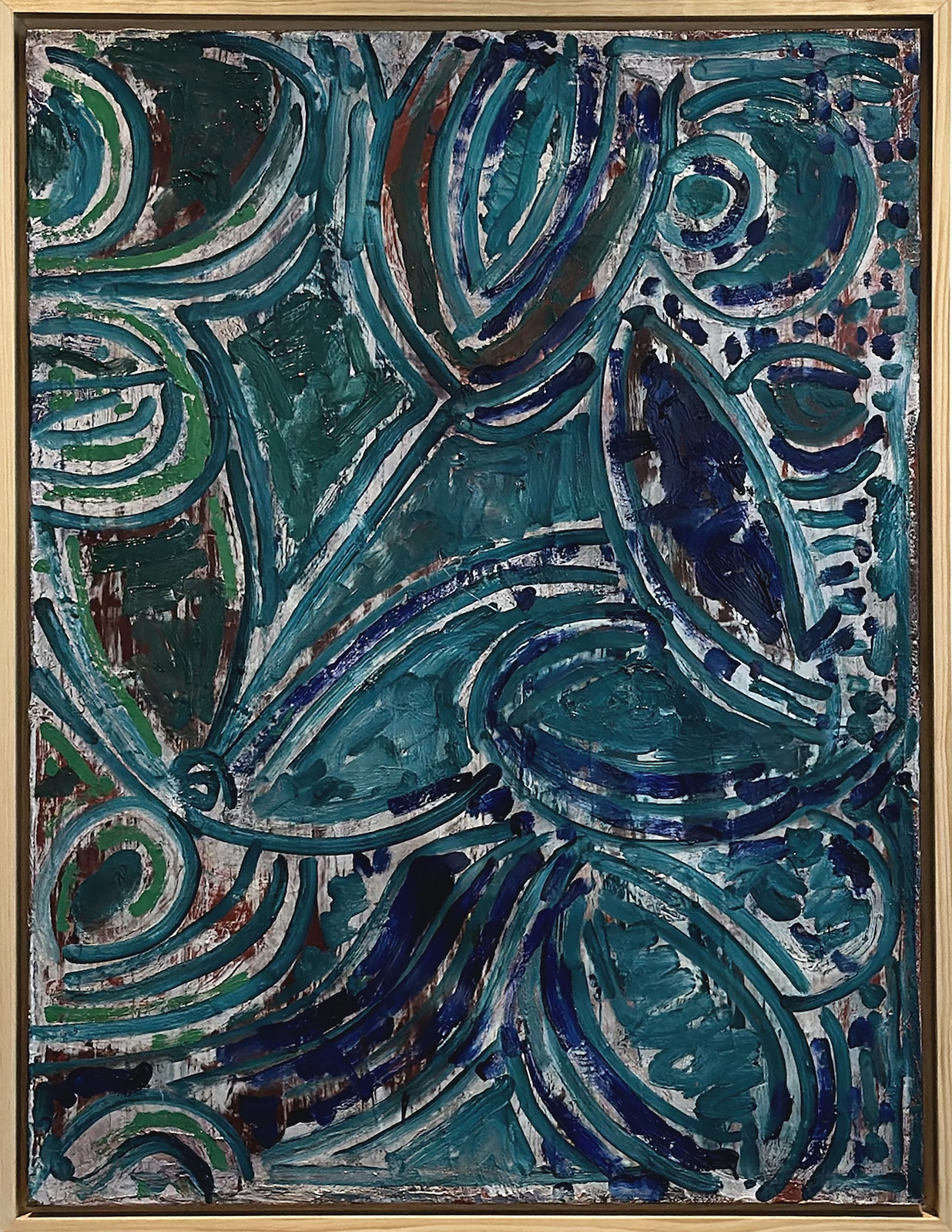

The world’s oceans and the fish that swim in them are also favorite images in “Ain’t Dead Yet.” The sculpture Moby Dick (1990, now in the Wayne State University art collection) is a virtuosic evocation, in found materials, of Captain Ahab’s mythic nemesis. The series Jonah and The Whale, ten paintings on vintage New York Times papers, tell what would have been a really big fish story if only there had been newspapers in Biblical times. The altered book Fish or Cut Bait recounts another, more intimate tale of idyllic fishing trips. A large assemblage, Great Fish of Ferndale, anchors the center of the gallery.

Eric Mesko, Jonah and the Whale (series), 1989, acrylic on New York Times

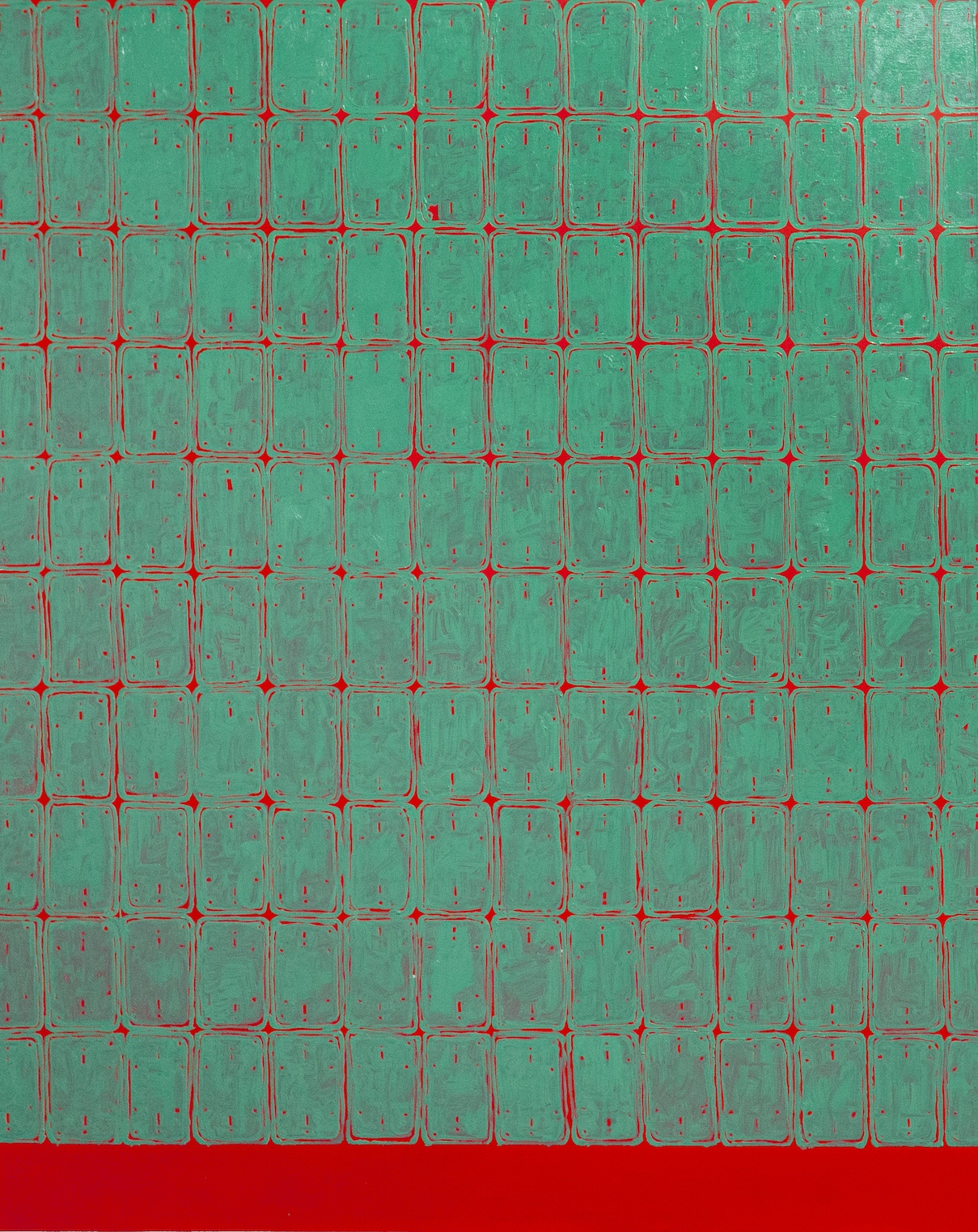

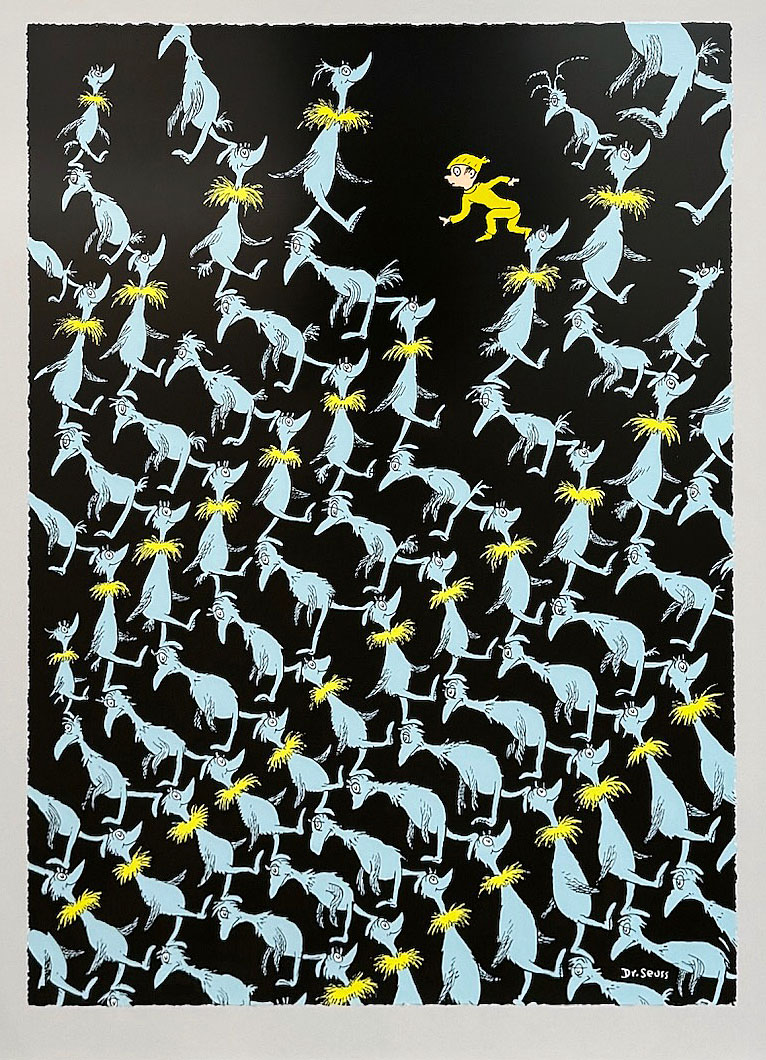

Mesko describes and critiques contemporary mass culture in America as more conformist, more materialistic and more predatory than the local, particularized regional artifacts and architecture of his American childhood in the 1940’s. “I grew up,” he says, “in the last era where idealism still meant something …The innocence of all that is lost but it wasn’t a fake innocence because in the late forties there was still a lot of idealism in the country and somehow that was important to me from an early age.”

Eric Mesko, American Voter, 1992, 9” x 12,” Ink on paper

After the initial shock and awe of encountering Mesko’s extraordinary vision, we begin to understand his unsentimental assessment of America and Americans. He may be a disillusioned patriot, but he retains enough optimism to keep working into his eighties. As he has put it, “We have to face our future head-on and accept our tasks with determination.“ Or, in the parlance of the show’s title, “We ain’t dead yet.”