Kayla Mattes – Doomscrolling Exhibition at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum, MSU, Lansing

Installation view, All works by Kayla Mattes. All images courtesy of Sean Bieri 2024

“Doomscrolling” is internet-speak for the online equivalent of a death spiral: the act of compulsively flicking at the screen of a smartphone and trolling for bad news, absorbing the steady stream of tragedy, atrocity, injustice, and outrage that the algorithm floats past our eyeballs until we’ve lost track of time, and possibly our grip on reality. (The corollary habit of compulsively seeking out tidbits of lightweight entertainment to counteract such horrors is an issue in its own right.) “Doomscrolling” isn’t just a buzzword; googling the term brings up pages on the National Institutes of Health’s website that associate the phenomenon with anxiety, depression, and other disorders. Textile artist Kayla Mattes’ exhibition Doomscrolling (open now through August 18 at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum, Lansing) is an engaging and often humorous attempt to pull the viewer out of this virtual tailspin by transposing the web’s cacophony of video clips, headlines, memes, and emojis into the more tangible medium of woven tapestries, allowing us to examine them at a remove, the better to reflect on how the internet is rewiring our brains.

Born in 1989, Mattes is a “digital native,” a child of the information age who can scarcely recall a time before the internet. Some of the individual memes she works into her tapestries have become classics of the medium; a few are golden oldies that may be as nostalgia-inducing for younger viewers as Saturday morning cartoons are for a Gen Xer. Many visitors will smile with recognition when they spot the “Awkward Look Monkey Puppet,” a synthetic simian who nervously shifts its gaze in response to some uncomfortable situation; the “This Is Fine” dog, a cartoon canine who smiles contentedly while the room burns down around him; and of course the iconic “Keyboard Cat,” a tabby pawing at an electric piano who “plays off,” Vaudeville style, the victim of some catastrophic personal failure in a series of memes that dates back to the primeval year of 2009.

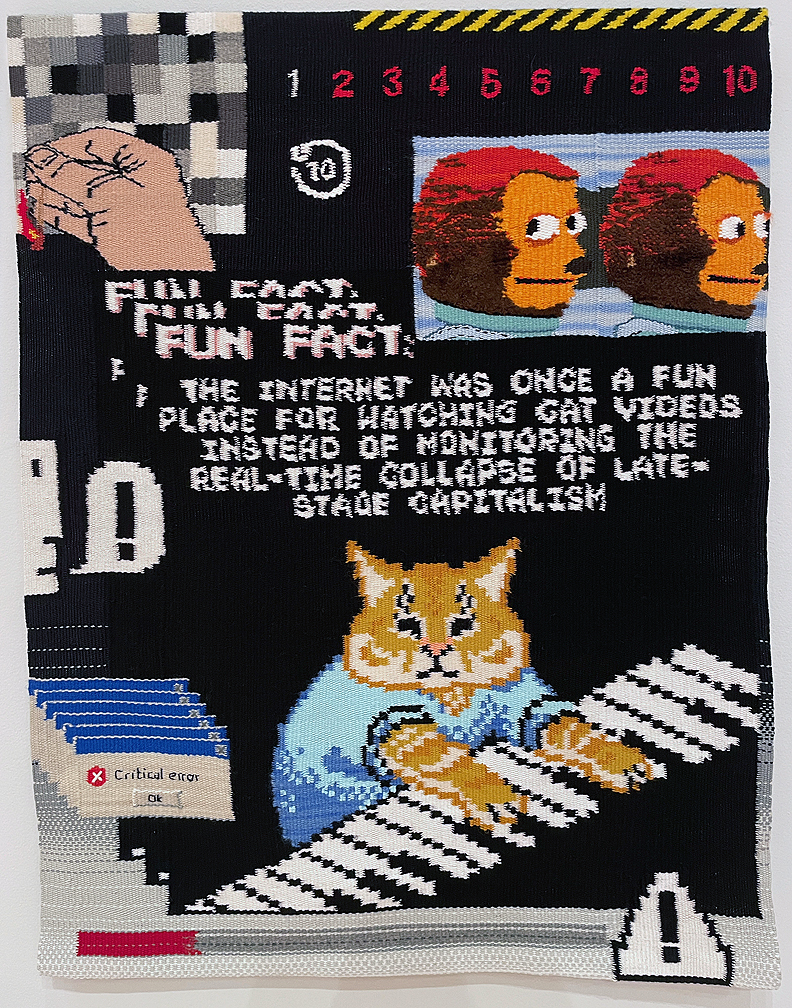

Kayla Mattes, Fun Fact, 2023, Handwoven cotton, wool, and acrylic

It’s fun spotting these familiar characters within Mattes’ tapestries, though it’s a bit like being a soup enthusiast at a Warhol show — focusing only on such details misses the larger point. Mattes collages all this digital detritus carefully to give each tapestry a theme. For instance, Keyboard Cat appears in a piece called “Fun Fact,” surrounded by warning icons, error messages, and a rewind button. The phrase “The internet was once a fun place for watching cat videos instead of monitoring the real-time collapse of late-stage capitalism” appears over the musical feline’s head so that he seems to be “playing off” the failed promise of the World Wide Web and the remains of our collective innocence.

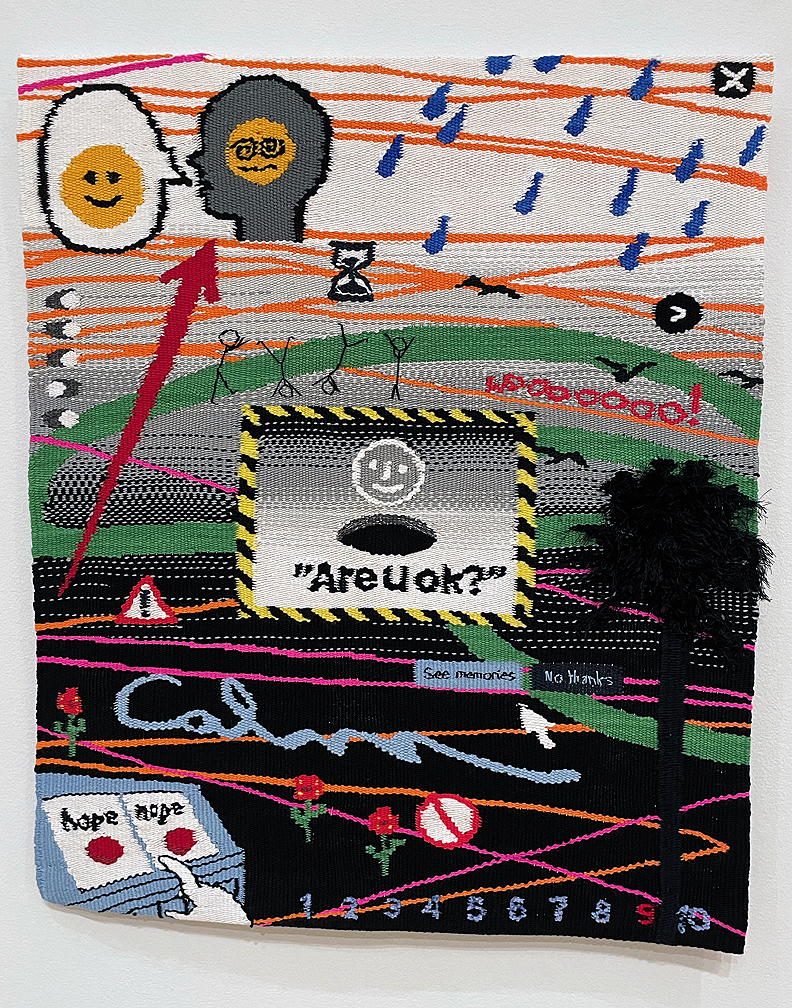

Kayla Mattes, Better Help, 2022, Handwoven cotton, wool, and polyester

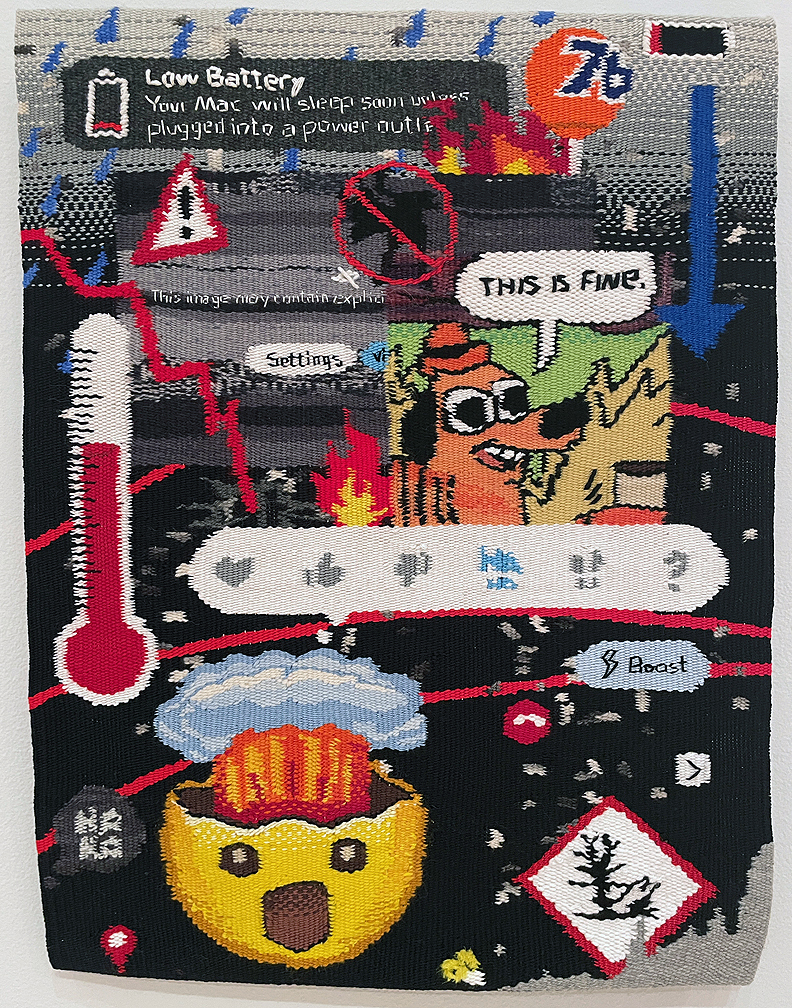

“Better Help” borrows its title from an online mental health service and features various images suggesting tension and anxiety: a finger poised over two red buttons labeled “hope” and “nope” (aka, the “Daily Struggle” meme); an hourglass icon; a smiley face hovering over a black hole. The “This Is Fine” dog — originally from a comic strip by KC Green illustrating our masochistic ability to acclimate to any “new normal,” no matter how calamitous — appears in a tapestry called “5%.” Surrounding the dog are images of flames, a rising thermometer, and the exploding head of the “mind blown” emoji, along with a “low battery” warning, suggesting that even as the global situation becomes increasingly heated, our ability to respond is dwindling. Another piece called “‘the apps’ (iykyk)” is strewn with the iconography of various dating apps, along with an image of Sesame Street’s Elmo engulfed in flames, and a map of the freeways of Los Angeles (Mattes’ hometown), both of which provide analogies for the frustrating hellscape that is the online dating scene. Other works in the show address climate change, commerce, and astrology.

Kayla Mattes, 5%, 2023 Handwoven cotton, wool, mohair, and acrylic

The juxtaposition of all this info-ephemera with the centuries-old handicraft of weaving may seem like an odd pairing at first (not as jarring as seeing attack helicopters and rocket launchers woven into an Afghan war rug, maybe, but the disconnect feels similar). It isn’t really as strange as it seems. After all, as Mattes points out, both computers and looms utilize a binary logic of sorts: the intersection points of warp and weft in a tapestry correspond to the on-or-off state of pixels on a screen. Plus, it was an early attempt at automating the weaving process, by one Joseph Marie Jacquard, that produced the punch card technology that made the first proto-computers — or “analytical engines” — possible.

Mattes worked with a modern Jacquard loom to create the centerpieces of the show, three vertical banners that hang down one wall and scroll out onto the floor. Each banner features a list of automated Google search suggestions prompted by the questions “What is…?,” “When is…?,” and “Why is…?” Not entirely random, the suggestions were based on searches trending on the internet at the time; they were then curated and arranged by Mattes. The resulting questions range from the existential (“what is wrong with the world today?”; “when is it time to move on?”) to the trivial (“why is comic sans hated?”; “when is an avocado ripe?”). Taken together, they paint a collective portrait of the internet community that’s reassuringly “relatable” — both humorous and endearing for the humanity that shows through the cold logic of the algorithm.

On either side of the gallery entrance, vertical strings have been hung so visitors can write their own “searches” onto strips of paper, then weave them — and themselves — into the fabric of the show. There’s also a demonstration video showing Mattes at her loom; at one point the artist’s cat appears, batting at balls of thread while Mattes tries to work, because how would an exhibition like this be complete without its very own funny cat video?