Kinship: The Legacy of Gallery 7 and From Scratch: Seeding Adornment, New Work by Lakela Brown @ Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit

Visitors to MOCAD this summer will have four new shows to enjoy, each adding a facet to the kaleidoscopic multicultural Detroit art scene. At the entrance to the museum, we find “Kinship: The Legacy of Gallery 7.” It’s a collection of significant objects and images providing a window into the art world of the late 1960’s, post-rebellion, when African American artists in Detroit achieved a collective sense of themselves and their purpose. Next, Lakela Brown’s first solo museum show “From Scratch: Seeding Adornment,” looks to a future that explores Black experience through racially specific foodways and styles of personal adornment. Drawing our attention out to the broader landscape, Meleko Mokgosi , a Botswanan artist and academic now living in the U.S., provides a scholarly examination of Black artists as they have seen themselves and are seen by others through the lens of colonialism and diasporic history. Lastly, in Mike Kelly’s Mobile Homestead, museum visitors will find a more informal conversation among the city’s artists, curators, and administrators on the collaborative nature of art presentation.

With apologies to the creatives responsible for “Zones of Non-Being” and “Word of Mouth,” and meaning no disrespect, l will concentrate here upon the artists represented in “Kinship” and “From Scratch. “

Kinship: The Legacy of Gallery 7

Those with a particular interest in the art history of Detroit and of the African American artists working in abstraction in particular, will have the pleasure of seeing a selection of work by some of the city’s most significant practitioners, many represented by the iconic Gallery 7, which showed outstanding work by Black (male) artists from 1969-1979. (In a spirit of retrospective reparation for past gender discrimination, Abel Gonzalez Fernandez, the curator of the exhibition, has also tactfully included work by several contemporaneous female artists, Elizabeth Youngblood, Gilda Snowden, and Naomi Dickerson.)

Fernandez has done an admirable job of telling the story of this seminal period in the city’s art history by employing a small, but choice, selection of artworks begged and borrowed from collectors, the artists themselves or their estates. A welcome bonus is a newspaper-style publication accompanying the exhibition, which includes a well-researched and written short history of the gallery by the curator. The compilation of contemporary press coverage that accompanies his essay goes a long way toward explaining the excitement that accompanied the art that was shown there during the gallery’s ten-year existence. It is also a melancholy reminder of how much the art audience lost when intelligent art journalism in Detroit’s mainstream newspapers ceased with the advent of the Internet.

Lester Johnson (b. 1937) The Sorceress and the Dreamtime Spirits, 1974, installation: wood, fabric, vegetal fiber, feathers, bells. All images courtesy of K.A. Letts

Several of the artists in “Kinship” take inspiration from African artifacts. One of the show’s highlights is The Sorceress and The Dreamtime Spirits (1974) 9 wall-mounted sculptures by Lester Johnson that mimic the form of West African ceremonial objects. The long rods made of found branches and poles are fabricated and decorated with industrial and post-industrial materials, a process Johnson describes as “creating a hybrid product between ancestors and urban present.”

Elizabeth Youngblood (b. 1952) Loop 8, 2015, porcelain and wire.

Loop 8, by Elizabeth Youngblood, subtly references Black personal adornment, a recurring theme in the art of female African Americans, as we see in Lakela Brown’s nearby solo show. (But more on that later.) Using the simplest means of expression, wire, and barely modeled porcelain clay, Youngblood teases out tremulous but insistent meaning from humble materials.

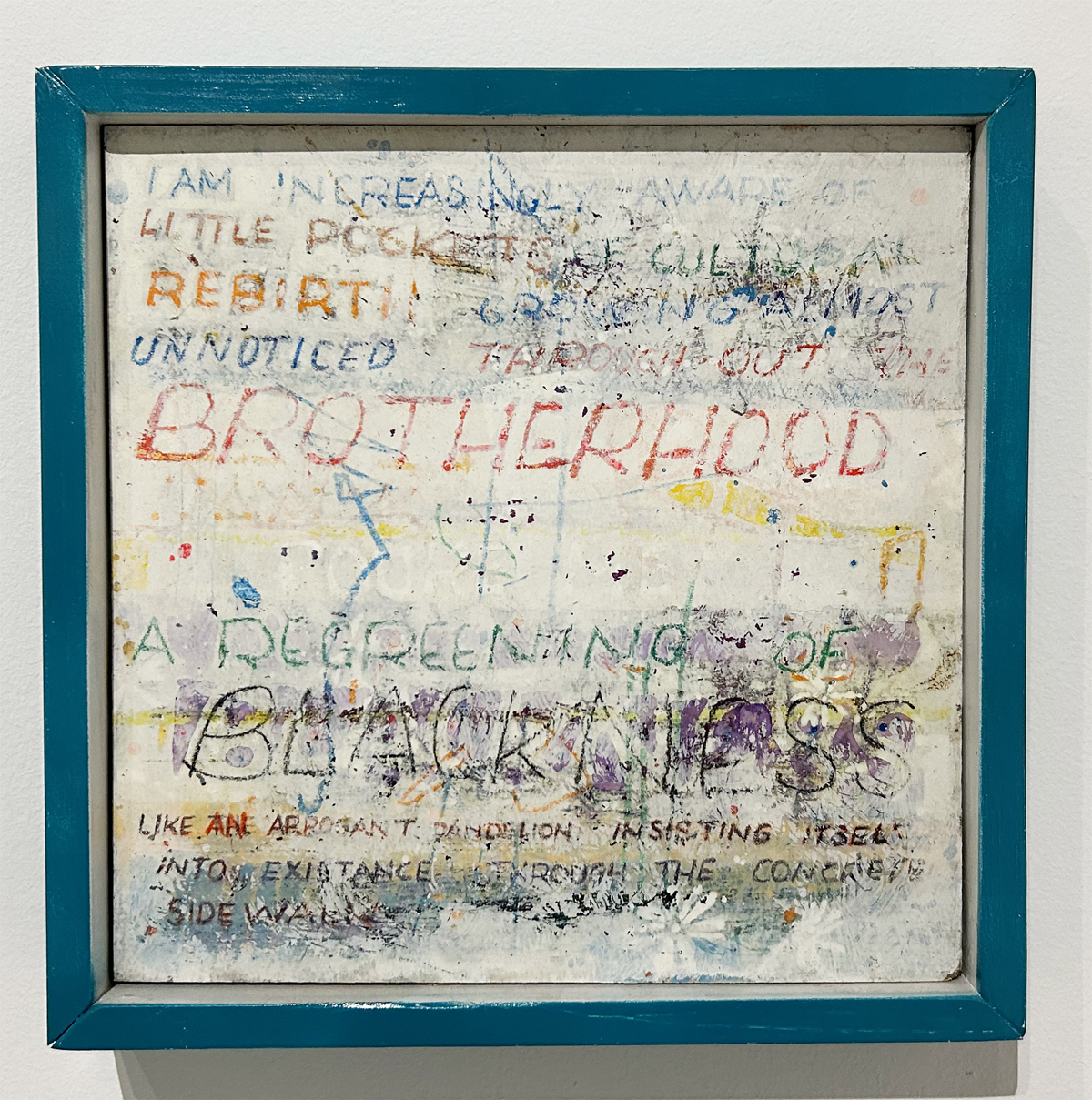

Harold Neal, a major figure in the Black Arts Movement of the 1970’s, is represented in “Kinship” by Brotherhood, a medium-sized, text-heavy artwork that wears its racial advocacy on its sleeve. The artist’s work, through the 1960’s and 1970s when Gallery 7 was in operation, was figurative and militantly political. As a movement leader, he led a faction of Black creatives whose radical work was in tension, if not in opposition, to the more cerebral concerns of his fellow gallery artists. (A recently published history of this group, “Harold Neal and Detroit African American Artists: 1945 through the Black Arts Movement” by Julia R. Myers, is available from Amazon.)

Harold Neal (1924-1996) Brotherhood, n.d., oil on board.

The art practice of the Gallery 7 artists focused primarily on their own personal experience as African Americans, or as gallery founder Charles McGee explained, “My roots are in America, and the ideas I deal with as an artist come out of this time and place.” McGee occupies a special position in Detroit’s art history. In addition to his importance as the force behind Gallery 7, he was an influential arts educator and a leader in the African American art community. Many of his public artworks can be seen throughout the city, and his importance was recently acknowledged by a posthumous survey of his work in the newly opened Shepherd in Detroit’s Little Village. Ring Around the Rosy, an early McGee work from the 1960s, is a tantalizing glimpse of the artist’s figurative work before he moved in a less conventional direction.

Charles McGee (1924-2021) Ring Around the Rosy, ca 1950’s, oil on board.

Allie McGhee, a significant Detroit artist honored by a major retrospective in 2022 at Cranbrook Art Museum, is represented here by a couple of lively abstract paintings. The Artist in his Studio (1973) is chromatically subdued, allowing the gestural line to take center stage. His recurring use of a personal icon, the banana moon horn, was first seen during his tenure at Gallery 7 and continues in his current work, a personal, idiosyncratic emblem of ancestral energy brought from the past into the present. Coco Blue (1984), a more colorful cousin to The Artist in His Studio, is typical of McGhee’s later work and exhibits the exuberant presence typical of his paintings.

Allie McGhee (b. 1941) Artist in the Studio, 1973, mixed media on Masonite.

Allie McGhee, Coco Blue, 1984, mixed media on Masonite.

Album, a self-portrait by Gilda Snowden, is a psychological and physical evocation of the artist, an embodiment of her tempestuous and elusive power. Her unexpected and premature death in 2014 cut short a promising career, but this painting preserves her positive presence. It is an enduring influence she shares with the eminent artists represented in “Kinship.”

Gilda Snowden (1954-2014) Album, 1989, oil on canvas.

Artists represented in “Kinship: The Legacy of Gallery 7” Namoi Dickerson, Lester Johnson, Charles McGee, Allie McGhee, Harold Neal, Gilda Snowden, Robert J. Stull, Elizabeth Youngblood. June 28-September 8, 2024

From Scratch: Seeding Adornment

LaKela Brown describes her first solo museum show, “From Scratch: Seeding Adornment,” as a love letter to her community. “I want to center culturally significant objects that challenge and hopefully correct historic […] notions of value and taste while loving the brilliance and ingenuity of my community,” she explains. Brown practices a kind of archeology in reverse—preserving present cultural artifacts for future appreciation rather than searching for ancient objects to excavate and exploit. She is looking forward rather than back.

Lakela Brown, Parts and Labor (Eight Collard Green Leaves, Five Hands) 2024, urethane resin.

Brown, who grew up in West Detroit, has filled two large galleries at MOCAD with resin and plaster casts of foods specifically related to the culture of the Black diaspora and objects of personal adornment, particularly doorknocker earrings. The materials she uses to create these artworks are well-known to artists and lend an air of elegance and permanence by their association with classical museum casts.

Lakela Brown, Doorway to Adornment, 2024, site-specific installation, urethane resin.

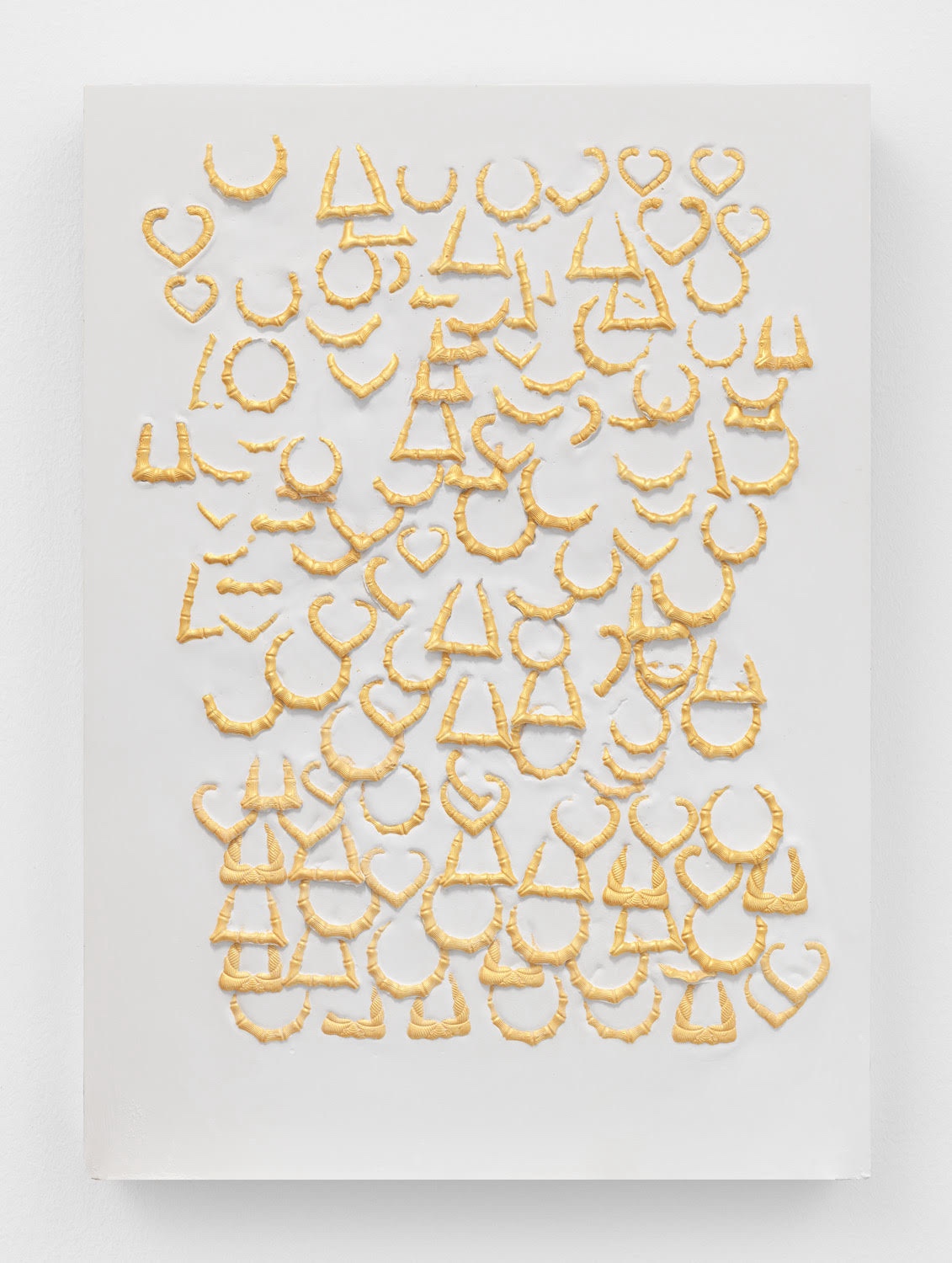

The first gallery features resin casts of vegetables– collard greens, corn, okra–artfully arranged on the gallery walls in square formats. In a surreal touch, and in tribute to her matriarchal connections, the artist tucks barely visible casts of the delicate hands of her grandmother, Evelyn Helen Brown, in among the vegetables. Though the usual designation for artworks featuring food is still life, these pieces, in the formality of their presentation and their low-relief arrangement on a rectilinear base, seem to be more architectural in nature. In particular, the ruffled edges of the collard greens call to mind decorative rococo details one might see in an 18th-century European drawing room. Brown makes the comparison explicit with the site-specific row of cast collard greens installed over the doorway to the second gallery, Gateway to Adornment (2024). With her casts of ethnically specific doorknocker earrings, chain necklaces, and other ornaments to the body—including casts of crowned teeth—Brown taps into a rich vein of visual associations she shares with many of her contemporaries. A case in point is the work of Tiff Massey, now on view at the DIA, which features hair ornaments—oversized ponytail ties and enormous replicas of Snaptite Kiddie Barrettes, as well as an entire wall of hair weaves. The exhibition’s curator, Jova Lynne, who also shares many of Brown’s creative interests in her own work, says, “Lakela’s practice is a mirror to Black legacies that encourage people across the diaspora, including myself, to take pride in reflections of home…In her work, I see the cultivation of land, the preservation of adornment, and the production of artworks acting as ledgers of Black life.”

Lakela Brown, Coverall Composition with Doorknocker Earrings. , Gold (2023) plaster

The exhibitions on view now at MOCAD emphatically demonstrate the interrelated nature of the art community in Detroit, a true commonwealth of creatives who share philosophies, exchange materials and cross-pollinate cultures. Born of common experience, each collection of artworks forms part of a contrapuntal melody–or maybe a jazz improvisation–of mutually reinforcing themes which flow from one gallery to the next and out into the city.

Kinship: The Legacy of Gallery 7 and From Scratch: Seeding Adornment @ MOCAD