Janet Crane-Conant, pictured in front of Peter Voulkos’ Plate, loaned the works she inherited from her parents that comprise A View of Earth: The Architect’s Eye – Select Ceramic Art from the Anne and George Crane Collection, on view at Ferndale’s Paul Kotula Projects through January 11. Photo: Jeff Cancelosi.

A remarkable collection of modern and contemporary ceramics, A View of Earth: The Architect’s Eye, will be at Paul Kotula Projects in Ferndale through January 11. The works, which many museums would kill for, were collected by Anne and George Crane, Grosse Pointers, who were, respectively, prominent modernist architects and the owners of a construction company.

Significant names are scattered throughout this 29-artist group show, including Kresge Eminent Artist Marie Woo, the former head of Cranbrook Ceramics, Jun Kaneko, UC Berkeley’s Jim Melcher, and Kurt Weiser, a longtime professor at Arizona State University.

A designer of elegant contemporary residences, among other structures, Anne (Krebs) Crane was born in 1924, and made it in a male-dominated profession that at the time was quite hostile to women. After graduating from the University of Illinois School of Architecture, Crane came to Detroit to study with Eliel Saarinen, but her timing was unfortunate. He died just before she was to start at Cranbrook. All the same, Crane’s work caught the eye of local architects, including Minoru Yamasaki, with whom she collaborated for a number of years before launching her own firm with a partner, Krebs and Fader.

Gallery owner Paul Kotula, a ceramicist and art professor at Michigan State University, knew Crane well, and calls her “a delightful person, both kind and generous, but strong too,” which might help account for her success in her chosen profession. Crane also served for many years as a board member at Pewabic Pottery and from 1993 to 1996 as president, where she refined her appreciation for ceramics – acquiring the discerning eye that’s evident throughout this engaging exhibition.

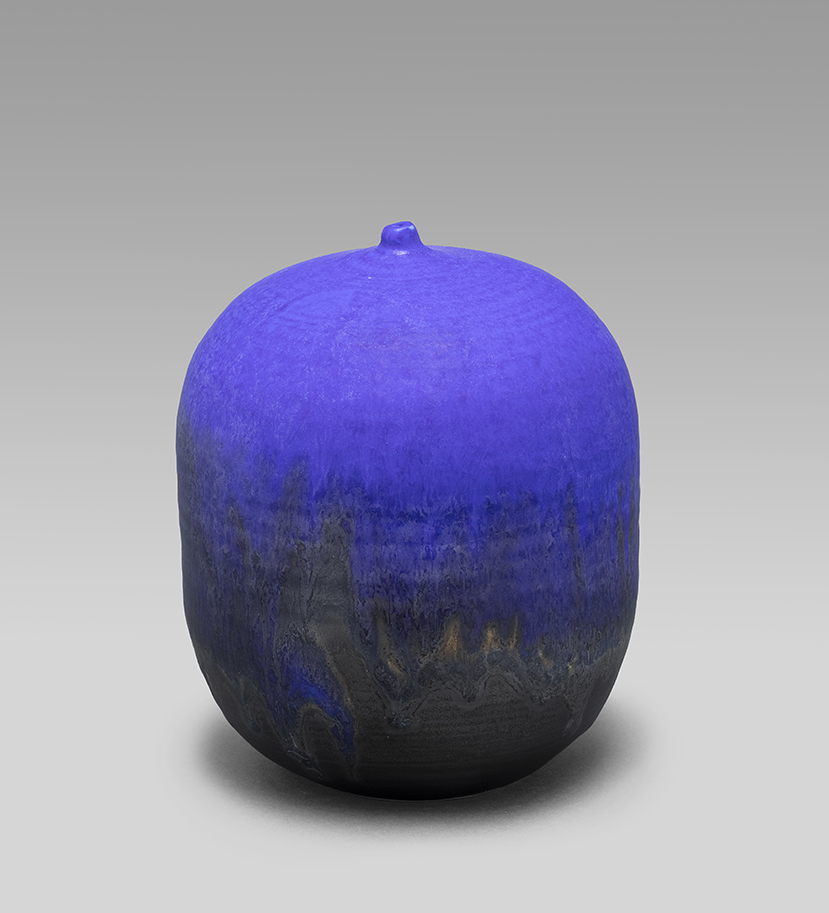

Toshiko Takaezu, Form #26, Ceramic with rattle, 7 x 5.5 inches, 1989. Photo: PD Rearick.

Anyone’s who already taken in Toshiko Takaezu: Worlds Within at Cranbrook Art Museum (up through January 12), will enjoy a jolt of recognition on spotting this diminutive “closed vessel,” emblematic of the radical work by this Cranbrook Academy of Art graduate who was a longtime Princeton University art professor. Just seven inches tall, this vessel with the slight indentation at its waist – another Takaezu hallmark – packs a wallop, in large part because of its ravishing blue. The word Kotula uses is “luscious.” He says, “It’s a little different from the forms at Cranbrook,” which have more deliberate markings on them. “This is just a very quiet landscape. In addition, the indentation gives a certain sort of softness that Toshiko was embracing. And I know for Anne Crane,” he adds, “blue was one of her favorite colors.”

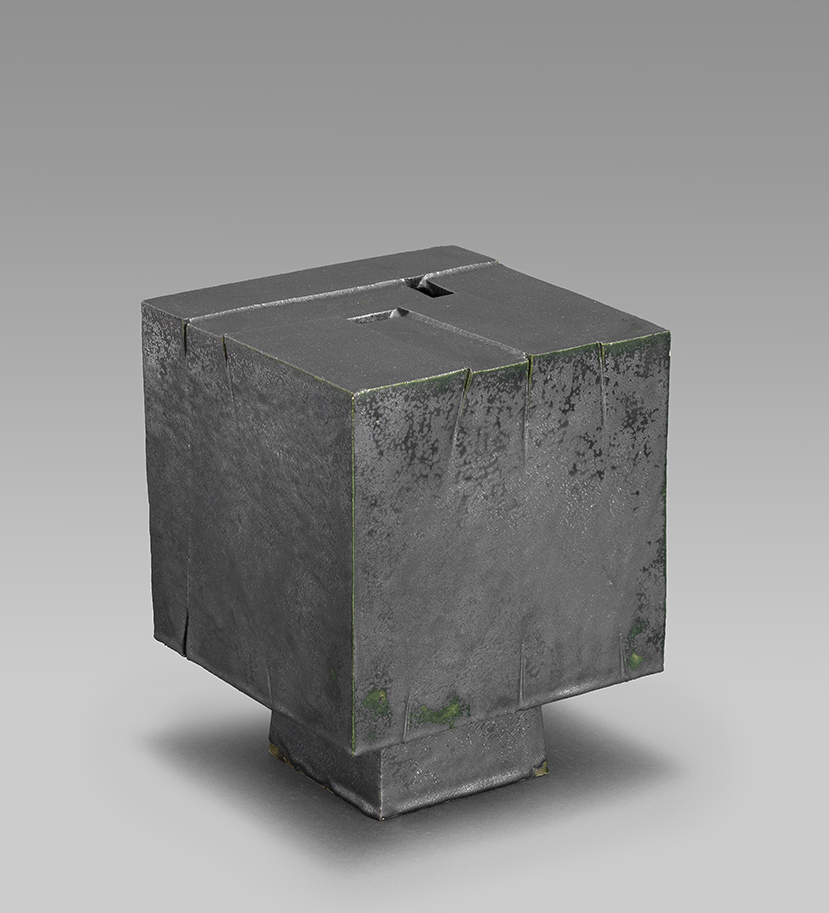

Otto Natzler, Cube with Fragmented Top, Ceramic, 8.3 x 6.6 x 6.5 inches, 1981. Photo: PD Rearick.

You could almost get whiplash moving from Takaezu’s vessel to Otto Natzler’s Cube with a Fragmented Top, which reads more like brutalist architecture than anything that’s made of kiln-fired clay. But you can totally see why a modernist architect like Crane might be drawn to such an unexpected ceramic form. An Austrian who fled Vienna six months after Nazi Germany annexed the country in 1938, Natzler and his wife and artistic collaborator Gertrud settled in Los Angeles, where their ceramics studio became one of the most influential on the West Coast. They had an intriguing division of labor: Gertrud threw the vessels, while Otto was known for his glazes. And with Cube, you readily see why.

Kotula points out that it’s fired with an unusual, high iron-content glaze. “it’s glorious,” he says. “It’s like steel, and keeps changing with light as you look at it.” Interestingly, he adds that after Gertrud died in 1971, Otto never threw another pot. Everything thereafter, like Cube, above, was made with slabs of clay.

Mary Roehm, Teapot, Wood-fired porcelain, reed handle; 11 x 11 x 10 inches, 1983. Photo courtesy of Paul Kotula Projects.

Other-worldly and quite marvelous is Mary Roehm’s Teapot, a composition that manages to look vaguely East Asian and futuristic at the same time. By comparison with the works above, this piece nicely demonstrates the expressive properties of unglazed porcelain. Known for her paper-thin wheel thrown or cast porcelain vessels, Roehm typically works without glaze so the effects of her wood-firing will be most obvious, and is known for manipulating her vessels, often tearing the edges or twisting them.

The artist got her MFA at the School for American Crafts at the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York. From 1987-1991, Roehm was executive director of Detroit’s Pewabic Pottery and has multiple works at the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Nicholos Homoky, Untitled, Porcelain, 4 x 4.5 inches, ca. 1982. Photo: PD Rearick.

Also exploiting the aesthetic possibilities of unglazed porcelain is Nicholas Homoky’s vessel, Untitled, an elegant exercise in milky white clay with rings of black. With its astonishingly smooth surface, the piece makes for an interesting contrast with Roehm’s Teapot, and its rougher, more-textured appearance. The Hungarian-born Homoky was educated at Bristol Polytechnic in England, where he still resides, and has work at both the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. “He’s known for this very simple, minimalist take on vessels,” Kotula says, noting that the rings here are actually inlaid black clay. “It is,” he adds, “just a beautiful piece.”

Marilyn Levine, White Ice, Mixed media, 6.25 x 8.5 x 4 inches, 1995. Photo: PD Rearick

Finally, it’s difficult to regard Marilyn Levine’s White Ice – a vessel dressed up like a shoe — without smiling. It will come as no surprise, then, to learn that collector Anne Crane, according to Kotula, had a great sense of humor. Levine, a Canadian artist who ultimately landed in northern California, participated in the funk-art movement of the 1960s and 70s, and became a master of what you could call trompe l’oeil ceramics. She was particularly famous for clay creations you’d swear were leather bags or jackets. Says Kotula, “She could render them to the point where they looked super-realistic” — a nice exercise in the pleasingly deceptive powers of art.

Installation image, A View of Earth, The Architect’s Eye, Paul Kotula Projects, 1.2025