Back on Willis Street, at Detroit’s Simone DeSousa Gallery

An installation shot at the opening of her solo show, Back on Willis Street, at Detroit’s Simone DeSousa Gallery. This image is courtesy of DAR.

Art-wise, New York is a famously tough nut to crack. Cass Corridor legends Gordon Newton, Bob Sestok and Michael Luchs all gave it a shot decades ago but, for various reasons, came back to pursue their careers in Detroit.

Not so Brenda Goodman, one of several talented women who gave the hard-drinking Corridor boys a run for their money back in the 1970s, a talented cohort that also included Nancy Mitchnick and Ellen Phelan.

At 80, Goodman – whose solo show of recent work, Back on Willis Street, is at Detroit’s Simone DeSousa Gallery through June 10 – has finally achieved the sort of success 99 percent of artists who flock to Gotham, stars in their eyes, can only dream of. “Brenda’s the best-known and most-successful artist of the Cass Corridor,” said gallery owner Simone DeSousa. “We have so many amazing, significant artists here, but their work and stories have never really gone much beyond local awareness.”

In a nice touch, Goodman’s Detroit exhibition comes exactly 50 years after her very first solo show. It was 1973 at the Corridor’s legendary Willis Gallery, some eight years after the artist graduated with a degree in painting from the old Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts (now the College for Creative Studies).

It’s been a big year for Goodman. Back on Willis Street follows hard on the heels of her solo show in Manhattan that closed in March, Hop Skip Jump at Sikkema Jenkins & Co., the big-deal gallery in Chelsea that represents the artist, who moved from Manhattan to the Catskills in 2009. Goodman’s work has always refused to bend to commercial whims and now commands impressive prices.

Brenda Goodman, This Is the House that Jack Built, Oil, mixed media on wood, 36 x 47 inches, 2022. Photos courtesy of Simone DeSousa Gallery.

Her early paintings were achingly personal, almost confessional. In the 1994 Self-Portrait 4, a grotesque humanoid with wild eyes is jamming globules of something – some say impasto paint – into her mouth, much of it dribbling down her huge frame with its skinny, almost vestigial arms. The piece is creepy, dark, and deeply unsettling; the self-loathing behind it hits you like a hot wind.

Some have tried to draw a line between those “diarist” works, representing a powerful emotion at a given moment in Goodman’s life, with the equally dark abstractions she switched to starting in 2010, giving up figurative paintings. But the artist insists the abstractions do not tell a story per se, and have more to do with her playing with shape and color than reflecting anything about herself. Her geometric abstracts are often slashed with deep incisions made with a linoleum cutter or Dremel drill press. Some have likened the carved lines to scars, which would fit with some of her painful figurative work, but Goodman doesn’t buy that.

“I don’t think it has anything to do with scarring,” Goodman told Hyperallergic in 2019. “I’m using the linoleum cutter to do automatic writing. I used to do it with black oil marks all across the surface. Now I’m just doing it with the linoleum cutter: pulling out and using the shapes and forms which are generated, and letting that lead to the next shape.”

And Back on Willis Street is about nothing if not shapes. In a work like the gorgeous Shadows of Love, purplish-brown triangles, trapezoids and rectangles are stacked like so many foundation stones, set off here and there by unexpected splashes of yellow, lavender and blue.

Brenda Goodman, Shadows of Love, Oil, mixed media on wood, 36 by 47 inches, 2022.

DeSousa, who’s an artist herself, calls Goodman “a painter’s painter,” one who’s been laser-focused on “constant exploration and a directness about how she approaches her work.” But the Back on Willis Street paintings, all done in the past two or three years, stand out among the abstractions she’s produced ever since a beloved dog died 13 years ago.

“These works are lighter,” DeSousa said, “with washes of color” not seen in much of the earlier work. In another shift, Goodman’s started including references to some earlier paintings in some of the contemporary pieces. With Shadows of Love, there’s a tiny figurative insert on the far right – a running woman with a traumatized-looking face.

Brenda Goodman, Shadows of Love (detail), Oil, mixed media on wood, 36 by 47 inches, 2022.

In many ways, Goodman’s turn to abstract paintings helped foster her ascent to the big stage. They also garnered heightened interest. Author, editor, and major local collector Suzy Farbman has a large Goodman hanging in her dining room next to a standing cross by Ellen Phelan. In her recent book, Detroit’s Cass Corridor & Beyond, Farbman wrote, “As Brenda worked her way from very personal, cartoon-like images toward a unique form of abstraction, I became more attracted to her work. Today,” she added, “I’m an unabashed fan.”

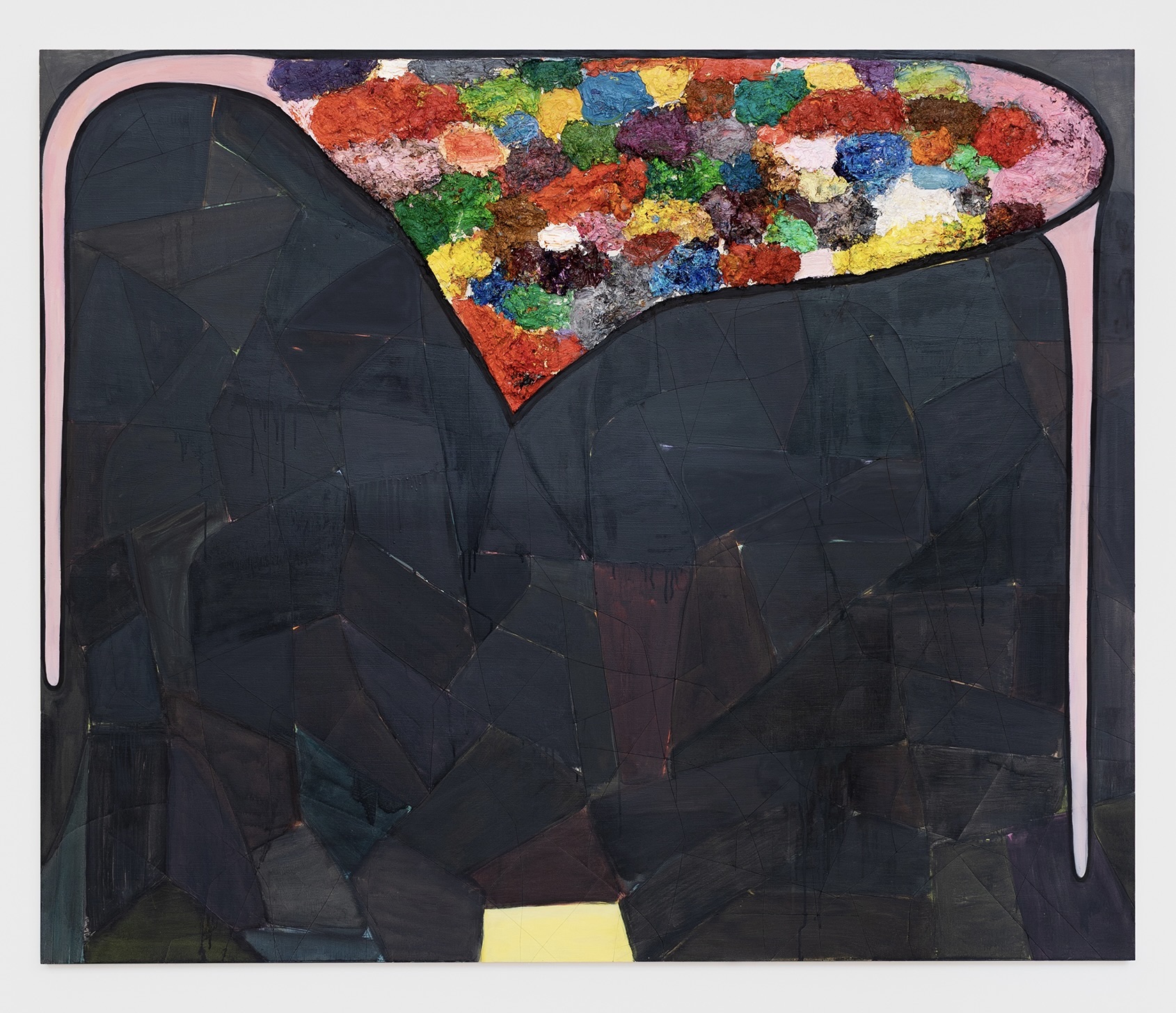

One painting, in particular, stands out among the collection at the De Sousa Gallery. Whose Winning has the feel of something oddly, dramatically different. Largely black and deeply scored, creating her trademark mosaic of shapes, the work is topped by a burst of many roundish colors, a bit like a bouquet, and two pink tendrils or “arms” that hang down and seemingly embrace the painting. And at the very bottom? An odd little yellow trapezoid that DeSousa says “balances” the whole work and also makes the black and bright colors alike pop.

Brenda Goodman, Whose Winning, Oil on wood, 60 by 72 inches, 202

DeSousa had long wanted to do a solo show for Goodman, and Back on Willis Street has been in gestation for some time. Reflecting on her origins, Goodman spoke about how different her work was from that produced by most of her Detroit compatriots back in the day. “My work was different from the other Cass Corridor artists,” she’s said. “They were mostly guys who used materials like barbed wire and surfaces with bullet holes. Detroit was a rough place, and they were representing the city. My work had a surreal feeling, and it was very personal. It was based on what was going on in my life at the time. But we were still a group, and it was really nice.”

Brenda Goodman, The Sun’s Gonna Shine, Oil on wood, 36 by 45 inches, 2023.

An installation shot of Brenda Goodman speaking at the opening of her solo show, Back on Willis Street, at Detroit’s Simone DeSousa Gallery through June 10.

Brenda Goodman: Back on Willis Street, at Detroit’s Simone DeSousa Gallery through June 10.