When Diego Rivera came to the Detroit Institute of Arts to create the Detroit Industry murals, the communist painter formed an unlikely bond with arch-capitalist Henry Ford over their shared fascination with technology. Ford had zero interest in art, but he was an avid collector of obsolete machinery, relics of the only sort of history he respected. When Rivera heard of Ford’s collection, he had himself driven to Dearborn early one morning and stayed until well after dark, poring over the metal menagerie that would eventually become the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

The intersection of art and technology is on display throughout the Henry Ford Museum: in Charles and Ray Eames’ playful “Mathematica” exhibit, in the quirky product designs of Michael Graves and the Apple graphical user interface created by Susan Kare, and in the array of works displayed in the Modern Glass Gallery. It’s a connection that’s further explored in Lillian Schwartz: Whirlwind of Creativity (open through March), the inaugural exhibit of the Ford’s new Collections Gallery, a space that will feature some of the museum’s more ephemeral objects that seldom go on display.

World’s Fair, 1970, Kinetic sculpture & Proxima Centauri, 1968 Kinetic sculpture

Schwartz is a pioneer in the field of electronic art. Beginning in the late 1960s, at a time when computer-generated art was still something of an anomaly, Schwartz collaborated with numerous engineers, programmers, and fellow artists to use the emerging technologies of the day in off-label ways to create her work. The Henry Ford recently received Schwartz’s archives and is still in the process of sorting through it all, but the current exhibit of 100-plus items is an exciting distillation of her life story. It features paintings, prints and drawings, sculptures, short films, plenty of ephemera from Schwartz’s long career, and, true to form for this museum, some of the gadgets she worked with, such as film editing equipment and projectors. It’s especially fortunate that this celebration of Schwartz’s work should be mounted while she’s still with us — born in 1927, the artist is now 96 years old.

Art supplies were hard to come by when Schwartz was a child, so she made use of whatever she could get ahold of — scraps of wallpaper, salvaged bits of sidewalk chalk, even leftover bread dough for sculpting. Some of her earlier artworks, from the 1950s, are on display here. Bright and colorful, they are decidedly analog but hint at the improvisatory ethic of her childhood and at the boundary-jumping approach Schwartz would apply to her art throughout her life: some feature collaged elements, others are painted onto overlapping layers of repurposed thin, translucent fabric rather than canvas.

On display nearby are some of her sculptures from the 1960s. They look wonderfully retro-futuristic, like they’d be at home on the set of a classic science fiction movie. In fact, one object called Proxima Centauri, a translucent globe that rises from inside a dark pedestal and flickers with colorful light when the viewer steps on a pressure pad, was used as a prop on the original Star Trek TV series (as well as appearing in the 1968 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, The Machine As Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age). Another work, World’s Fair, a glowing box full of spiraling glass tubes that siphon up multicolored fluids, could be the circulatory system for some cybernetic organism. The tubes were trash-picked from a glass factory, and the red and green liquids coursing through them were originally cough syrup and creme de menthe!

Grandma and Grandpa, Etching, 1975

In 1968, Schwartz was invited to come to Bell Labs, the storied incubator of tech innovation, as part of an initiative to humanize computers in the eyes of the public. “Technological pointillism!” she declared upon seeing an image at Bell of a reclining nude woman comprising a grid of hundreds of computer code glyphs. The nude had been printed out by a couple of Bell programmers as a joke, but Schwartz saw the real art-making potential in the technology. Hopping back and forth between the analog and digital worlds, she first drew faces onto graph paper, fed them into computers to be encoded, and then made silkscreen prints of the resulting pixelated portraits.

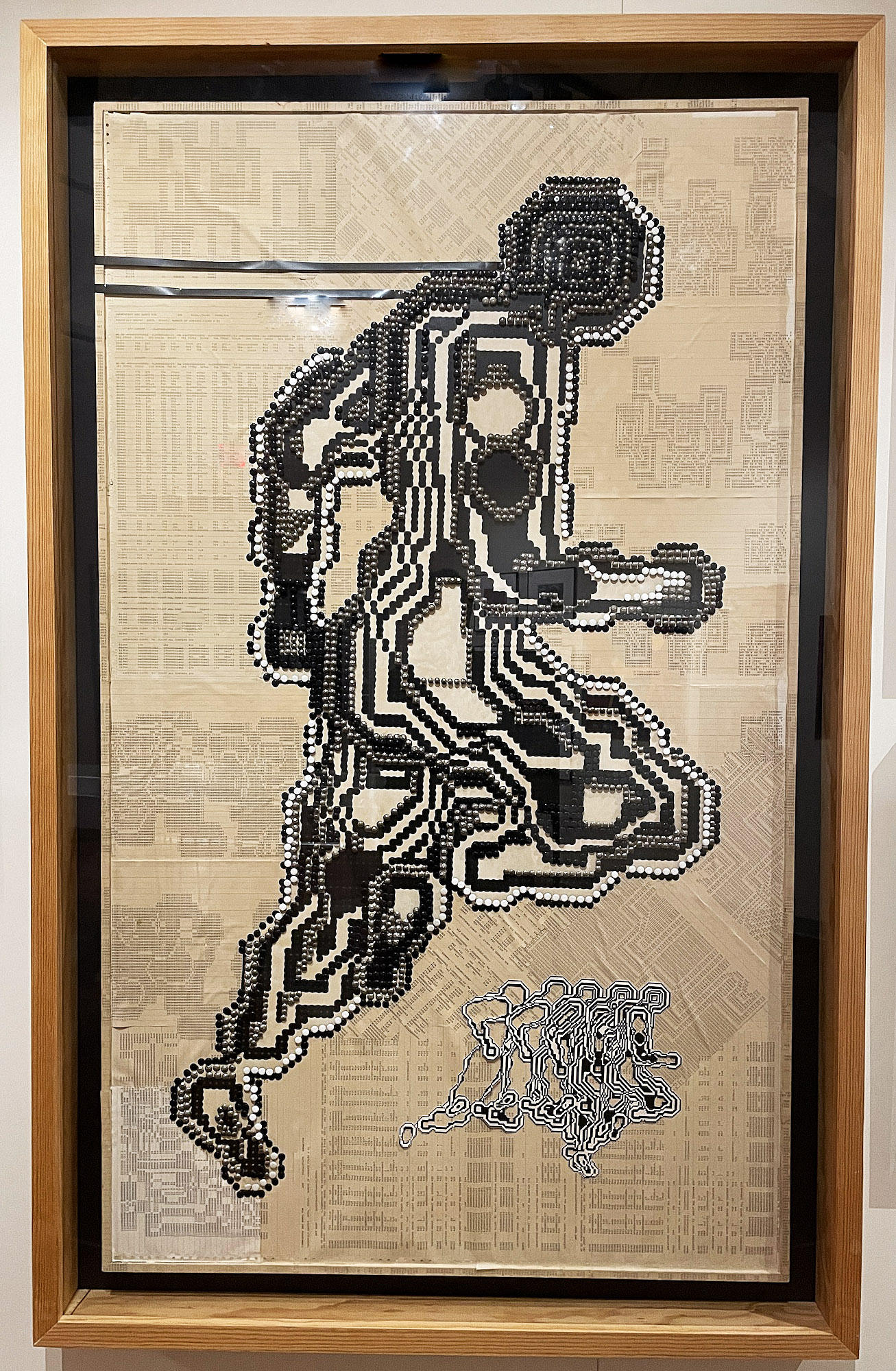

Later, using Bell’s circuit etching equipment, Schwartz rearranged the mazes and starbursts of circuit boards to create two figures she named Grandma and Grandpa; appearing both high-tech and primordial, they suggest totems erected to ancestors yet to be born. She used the same technique to create a streamlined variation on a Marcel Duchamp masterwork; hers is called Nude Ascending a Staircase. It doesn’t function as a circuit board anymore; it’s “merely” art, an homage that the Dadaist disruptor and creator of Fountain would no doubt have appreciated.

Still from Olympiad, 1971, Film transferred to video

In the center of the exhibit is a small black-box theater showing a number of short animated movies Schwartz made in collaboration with technicians and fellow electronic art and music innovators. Again, she melds the physical with the nascent digital technologies; one film includes abstracted images of a brain scan, while another juxtaposes matrices of growing crystals with distorted laser beams that waft around onscreen like deep sea creatures. In Olympiad, Schwartz animates digitized photos of a running man borrowed from Eadweard Muybridge’s groundbreaking motion photo series of the late 1800s (another technological advance that affected the art that came after). She later created a life-sized analog image of this pixelated athlete using a grid of black and white thumbtacks, once more swerving across the boundaries of different media.

In an era of sophisticated CGI, when video games are nearly as realistic as blockbuster movies and the “uncanny valley” gets narrower every day, it may be too easy to regard Schwartz’s films, with their chunky graphics, vivid color, and bleeping soundtracks as quaint baby steps toward modern computer animation. But they deserve to be appreciated on their own merits. They are by turns whimsical, hypnotic, and disorienting, sometimes like racing at warp speed through a Color Field painting exhibit, other times like drifting into a psychedelic dreamscape in which the acid-colored eyes of swirling galaxies seem to stare back at you.

Olympiad, c. 1970, Mixed media collage

There’s much more to explore in this exhibit: how her bout with polio while living in post-war Japan affected Schwartz’s art, and how scar tissue in one of her eyes caused her to see “Picasso-like” visions; her pioneering TV spot for MoMA, the first computer animated advertisement to win an Emmy; her attempt to use computers to prove that Leonardo’s Mona Lisa was partially a self-portrait (a dubious theory, but an interesting use of the software). There are also her run-ins with sexism and her sometimes awkward relationship with the suits at Bell Labs. In the mid-1980s, after many years of involvement with Bell, Schwartz was finally given a job title of sorts — “resident visitor,” an appropriately sci-fi-sounding designation. She was also called a “morphodynamicist” in order to make her seem sufficiently scientific to visiting Bell shareholders. Schwartz once half-jokingly referred to herself as a “pixellist.” But whatever her name badge reads and whatever high- or low-tech media she takes up, Schwartz is an artist through and through. In the midst of current debates over how artificial intelligence will disrupt the art world, Lillian Schwartz: Whirlwind of Creativity is proof that it’s the human being wielding the tools that will always make the difference.

Lillian Schwartz: Whirlwind of Creativity @ Henry Ford Museum on display through March 2024.