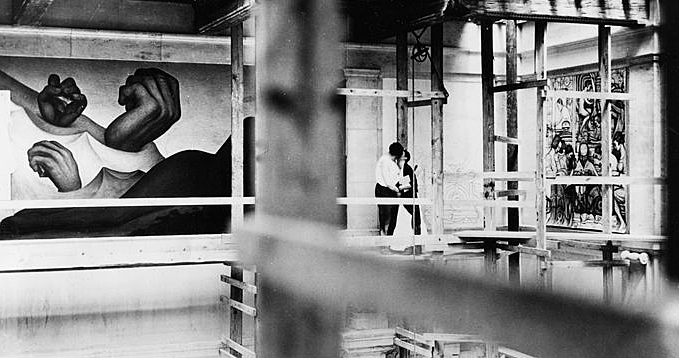

Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo kiss on the scaffolding of Rivera’s mural Detroit Industry, at the Detroit Institute of Arts.Photo: W.J. Stettler 1932-1933 / Detroit Institute of Arts

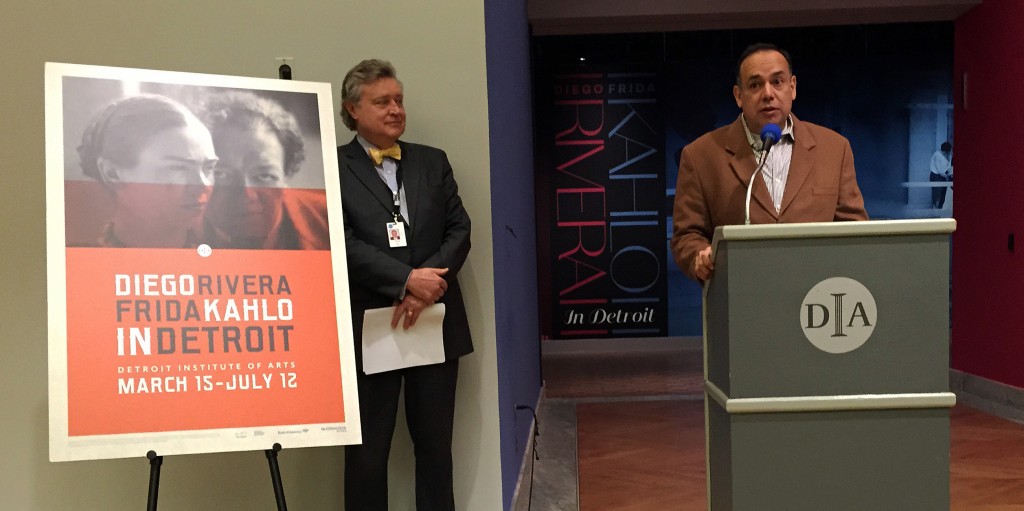

When Director Graham W. J. Beal took the podium to introduce the opening of the new Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit exhibition, he reflected on how long the show was in the planning. It had been nearly ten years. He reflected on this accomplishment in bringing this exhibition to Detroit.

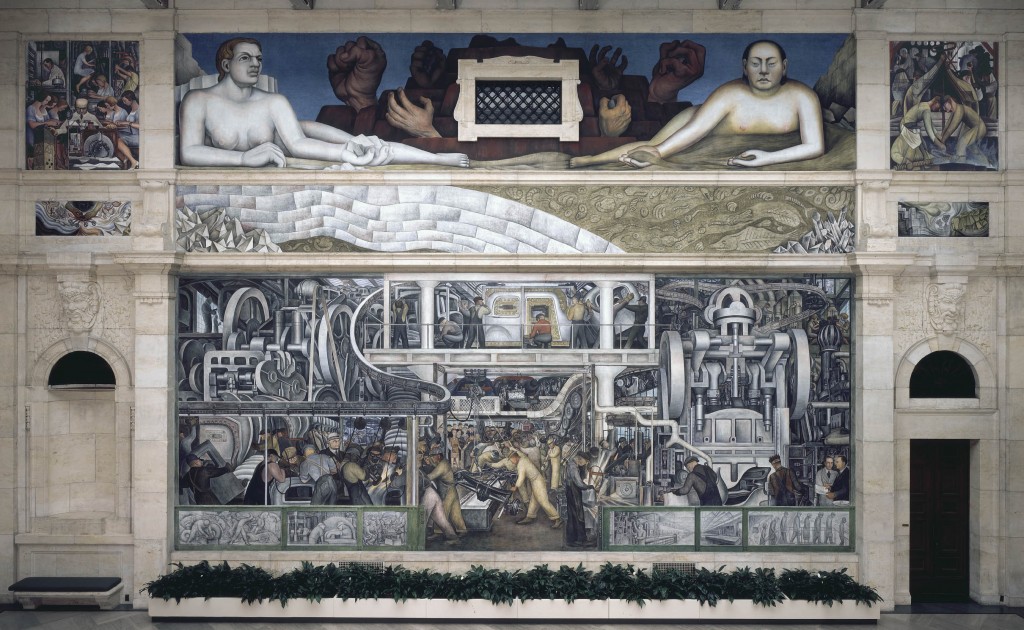

“Rivera considered Detroit Industry, recently designated a national historical landmark, as his finest mural cycle. It shows the artist at the height of his powers. For Frida Kahlo, on the other hand, the works she produced while in Detroit can be seen as the beginning of her development as a mature artist with her own distinct—and distinctive—style.”[1]

After his introduction and within minutes of completing his remarks, he stood and watched Juan Coronel Rivera, grandson of the famous artist deliver his remarks with a feeling of respect and accomplishment. Rivera talked about his grandfather’s mural work, both in the United States and Mexico.

The exhibition chronicles Rivera and Kahlo’s year spent in Detroit (1932-33) living at the new Wardell Hotel on Kirby Street across from the Detroit Institute of Arts. The building has now been transformed into the Park Shelton Condominiums, and on the list of the National Register of Historic Places. The couple had just married in Mexico in 1929 after a yearlong courtship where Rivera began traveling to the Kahlo house in Coyoacan, a suburb of Mexico City. Coincidently, it was the same year that the Mexican Communist Party removed Rivera as a member. It was also a year of turmoil for Mexico as northern generals raised armies to revolt against the government. But Rivera always seemed to place art above politics and positioned Frida Kahlo prominently in his mural panel, The Arsenal, at the Ministry of Education in Mexico City in an attempt to promote national pride and culture. In 1931 Frida Kahlo painted a double portrait of herself and Diego in San Francisco commemorating their wedding.

Diego Rivera was lured to Detroit by William Valentiner, the then director of the Detroit Institute for the Arts, who had met Rivera and his wife at the Pacific Stock Exchange Luncheon, in San Francisco in 1931. They were both invited to a dinner at the home of Helen Willis Moody who had just modeled for Rivera as he completed the Stock Exchange mural that year and it was there Valentiner had met the couple. He envisioned murals in the garden courtyard at the Detroit Institute of Arts.

“As soon as I returned to Detroit, I proposed to the Art Commission that we bring Diego to Detroit, knowing that the courtyard had the only plastered walls in the museum.”[2]

After being hospitalized for acute tendonitis in her right leg, it was November 1931, when the couple set sail for New York City where Diego Rivera was having a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. He was honored to follow artist Henri Matisse by the new museum. From there, they would travel to Detroit, where Rivera had secured a commission to paint two frescos capturing the automotive industry of Detroit. The relationship with Detroit began in March 1931 with Valentiner and his assistant director E.P. Richardson, when they curated an exhibition of Rivera’s drawings and watercolors to build enthusiasm for his work. It was with the financial support of Edsel Ford who was then serving as the Chairman of the Arts Commission that Rivera’s contract was consummated, and preliminary drawings were accepted.

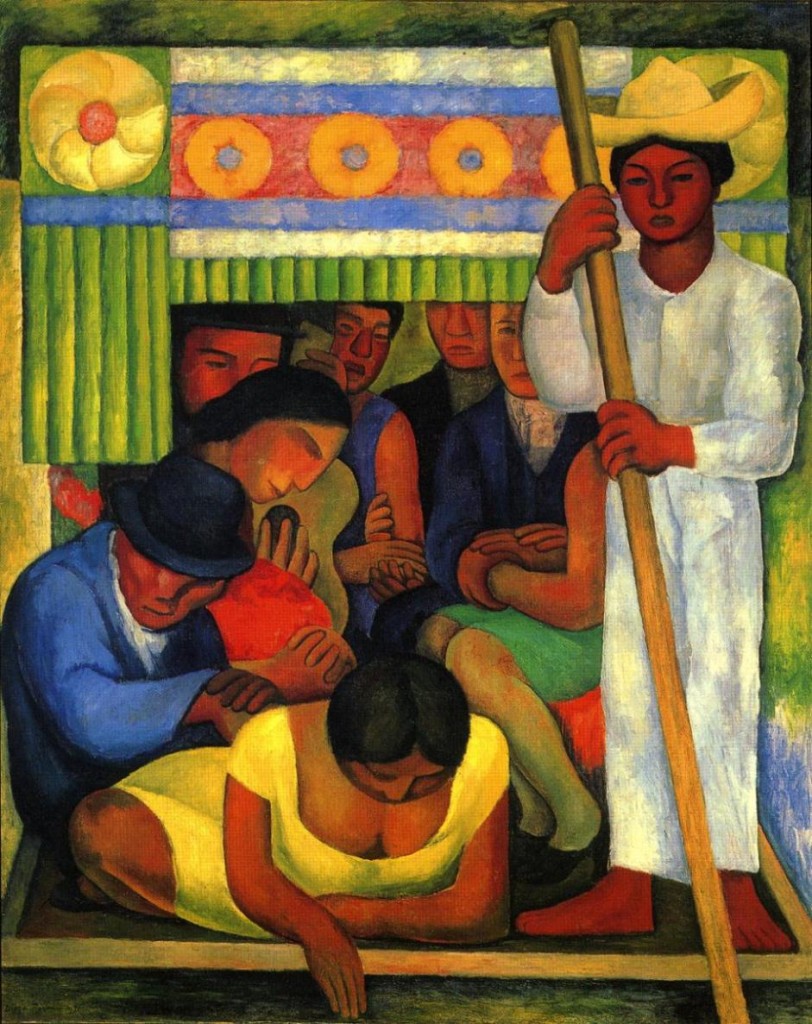

While in art school in Mexico City, Rivera studied with Santiago Rebull where he learned to model the figure with smooth continuous shading. He realized the influence he experienced in Europe, both in Spain and Paris. It is well documented that Rivera spent ten years, 1909-1921, in the company of Picasso, Braque, Juan Gris, Seurat and above all Cezanne. He was drawn to the mathematical construction using the ‘golden section’ but by the time he left Europe, he was thinking about public art, which Cubism never intended to be.

He remembered, “Gone was the doubt and inner conflict that tormented me in Europe. I painted as naturally as I breathed, spoke or perspired.”[3]

Although Rivera had completed a large number of easel paintings, it was the art of fresco painting that dominated his interest during this period. It was his early study of Giotto while visiting Italy, more than any other fresco painter, that we see him at his best. In his murals the density and economy of the massive figures evoke Giotto’s Stations of the Cross in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy.

Included in the exhibition are the life size drawings on paper, referred to as ‘cartoons’ and are displayed in the second large room of the exhibition. These ‘cartoons’ were created on draftsman paper to fit the actual size of the fresco panel.

The outlines on the ‘cartoons’ were perforated with small holes while pinned to the panel. A cheesecloth pouch, filled with pigment, was pounced through the holes of the paper leaving a line-work of dots. These dots would become the guideline for the final plaster coat containing pigment. Because fresco painting has not been used much in recent decades, and for many people the fresco process would be unfamiliar. Essentially, distilled water is added to lime powder and sand which chemically raises the mixture to somewhere near the boiling point. After two coats of plaster are applied, the finish coat called intonaco, made of thoroughly slaked lime and finely ground marble dust, are combined with pigment. As this hardens, the chemical process makes the pigment one with the plaster.

Frida Kahlo’s work in the exhibition includes some early paintings and drawings, but the focus is on her paintings created in Detroit. The centerpiece painting is Henry Ford Hospital depicting her condition in the wake of a miscarriage in July 1932 where she presents herself on a bloodstained hospital bed that alludes to the various aspects of experiencing the trauma of a miscarriage. Introverted and introspective, Kahlo made nearly fifty self-portraits in her lifetime’s body of work. However, it would not be until the 1970’s, primarily in the United States, where many artists and historians saw the modernism in her work, a combination of obsessive surrealism, Mexican folk-art, and feminism. Throughout the exhibition, the photographs of Kahlo are abundant and documented in videos. She confronts her audience in traditional Mexican dress, hair high on her head, single eye-browed and often having a subtle mustache. It was an expression that during her time was rarely seen in the work of women artists.

Diego Rivera was a giant among artists of his time. He was an accomplished painter with murals that dominated both North and Central America during the first half of the twentieth century. There were two hundred paintings produced during his ten years in Europe, studying the Cubist movement that produced scores of easel paintings, drawings, and prints. In 1986, the Detroit Institute of Arts, organized a large retrospective of Rivera’s work, largely based on the discovery in 1978-79 unpublished material including the full-scale cartoons. The Detroit Industry murals witnessed by visitors from all parts of the world when visiting the courtyard, find that Diego Rivera was an extraordinary artist with a sophisticated, allegorical power that transcends time.

A tumultuous year is now behind the DIA that ended in a victory for everyone who escaped the jaws of bankruptcy that had threatened the City of Detroit and it’s beloved Museum. With this exhibition and the transition to new leadership at the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Museum could begin a new renaissance. That change would embrace new and experimental exhibitions along with past artistic accomplishments, and find new ways to better embrace the vibrant and progressive Detroit artist community.

Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo In Detroit

Detroit Institute of Arts March 15 – July 12

Tickets are timed, entrance on the half-hour.

$14, adult; $9 ages 6-17, Tue.-Fri.

$19, adult; $9 ages 6-17, Sat.-Sun.

Regular museum hours: 9 a.m.-4 p.m. Tue.-Thu., 9 a.m.-10 p.m. Fri., 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Sat.-Sun. During exhibition, DIA will remain open until 10 p.m. on Thu., and, starting May 26, until 7 p.m. Sat.-Sun.

313-833-7900

[1] DIA Press Release, March 15, 2015

[2] Pete Hamill, Diego Rivera, P. 76

[3] Pete Hamill, Diego Rivera, P. 150