Nancy Mitchnick, Installation at MOCAD, 2016 – Courtesy of MOCAD

Nancy Mitchnick has had a spate of exhibitions this past year. She had a great show at Hamtramck’s Public Pool, showed a few earlier works in a cool three-man exhibit at the iconic Detroit gallery, Alley Culture, and really opened some eyes with new paintings at Wasserman Project. The exhibitions signify a return to and embrace of her hometown after she escaped from the Cass Corridor art community in 1973, and lived and worked as a painting professor and artist for years in New York (Bard College), California (CalArts), and Massachusetts (Harvard). She was also honored as a Kresge Fellow in 2015, and most recently was selected by the prestigious American Academy of Arts and Letters as a recipient of the organization’s 2016 art awards. Quite a homecoming!

The most recent iteration of her work is in the big room of the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD). The huge gallery of MOCAD seems like it was made for Mitchnick and she comfortably fills the space with what at first seems a most curious selection of paintings—ranging from two portraits of a friend and three portraits from her “Wonder Women” series, to a work in progress recovered from what she herself calls a “bad” painting (about which she recently lectured at MOCAD), a couple of expressionistic still lifes, two landscapes and nine houses from her old neighborhood, and two new “narrative paintings.” In a sense the show constitutes a mini-retrospective of the range of Mitchnick’s work over the past thirty years—portraiture, still life, landscape—and two new, auspicious paintings that signify a leap into her future. But much more poignantly, “Uncalibrated” (the title of the exhibition) seems to explore Mitchnick’s quest over the years to mine the vast rhizoid root system of painting, to find out what being an artist is and what it can do, and what it will come to be. (In mock despair she exclaimed, “Sometime my studio looks like a group show.”) “Uncalibrated” is fundamentally a self-portrait, or perhaps a memoir, of Mitchnick as painter.

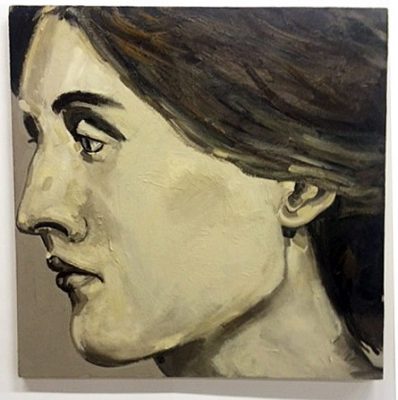

Nancy Mitchnick, Oil Painting 48 x 48, “Virginia Woolf”, 1990-91 All following Images Courtesy of Glen Mannisto

At the entrance of MOCAD are three early portraits, from the Wonder Women series, of Virginia Woolf, George Eliot, and Frida Kahlo. Painted in grisaille-like, gray shades that produce a classical sculptural effect, the heads of these three great, prototypical, feminist artists have a heroic scale and echo both Renaissance sculpture and certainly Enlightenment ideals. That they are outside of the main gallery, at the entrance, provides a hint of what part these heroic women might play in Mitchnick’s life as a painter. All three were experimental, independent, rational and investigative, secular beings and certainly, like Mitchnick, lived large lives. They also suggest a classical meta-literacy—to challenge the status quo, to invent, hybridize, psychoanalyze, to utilize—that is certainly part of Mitchnick’s own strategy as an artist. In her conversation with Jens Hoffmann, MOCAD’S Susanne Feld Hilberry Senior Curator at Large, she admits to being a voracious reader, which somehow parallels and infiltrates her work as an artist.

Nancy Mitchnick, Eye Detail, Oil Painting, 1992 -” Davy Butler First Hit”

Nancy Mitchnick, Detail of Eye Painting, 36 x 36 “Davy Butler Finished” – 1992

Her two portraits of a friend and patron, “Davy Butler: First Hit,” and “Davy Butler: Finished,” are elegant illustrations of Mitchnick’s carpentry skills in building these paintings, readily apparent throughout all of her work since. (“My father was a cabinet maker, but sometimes had to frame houses to make money.”) In “First Hit,” eyebrows and eyes are a dozen or so quick brush strokes—they are elegant and deft, making a sketchy, speculative architecture. “First Hit” is more mysteriously suggestive than descriptive, framing the first marks of the physiognomy of identity. Then in “Davy Butler: Finished,” the painting confidently assembles itself around the subject’s eyes. The head is smaller, more contained, and from each part of the facial landscape—the nose, the lips and mouth, and the eyebrows are precise—a commanding, almost Roman presence emerges. While making portraits to earn money, Mitchnick disavows a preoccupation with likeness, with making a painting that looks like the subject: “”Making likeness is not good painting, I’m making great paintings.” Her process, she says, is “all trial and error,” sometimes “losing whole beautiful passages to erasure, to get it right, to make a good painting.” In an offhanded aside she adds, “you writers just keep a record in your computers of every version of what you do. I lost a beautiful turtle here,” she muses pointing to a spot on the recent painting “Night Heron.” However not surprisingly, “Davy Butler: Finished” (the portrait of the friend who attended her recent MOCAD conversation with Hoffman), is not only an extraordinarily articulate painting, but an ennobling likeness as well.

Nancy Mitchnick, Two Portraits, “Davy Butler First Hit” , “Davy Butler Finished “, 1992, both 36 x 36

The heroic scale that she is given to (“I didn’t realize at first that I was a heroic scale painter”), necessitates a physicality and energy apparent in most of these recent works (as well as in her person). Fortunately disregarding all of the foreboding claptrap about “Ruin Porn,” Mitchnick took scores of photos of her old neighborhood near and around Hamtramck and began working from them during her first return to Detroit after losing her Harvard position to a “Conceptual artist.” (“I wanted to do something with Detroit.”)

Nancy Mitchnick, “First House”, 34 x 45 Oil Painting, 2006

The centerpieces then of “Uncalibrated” are the nine flat, elevation portraits of Detroit houses in various states of devolution. Depicting mostly the homes of working class people and perhaps middle-class families who ran small businesses or auto industry management, these are not memorials nor documentation of the state of derelict Detroit, but exquisite paintings that celebrate a presence of people who built and inhabited this place. Even the smallest painting, “First House,” exudes a very particular ethos and an aesthetic filled with a humanizing spirit.

Nancy Mitchnick, “Torn Orange”, Oil Painting, 59 x 99, 2009

In reminiscing about her Cass Corridor days, Mitchnick talked about wanting to be an abstract painter but was never able to escape narratives but perhaps, ironically, that has finally (almost) been achieved in two of the most monumental paintings in the exhibit. “Torn Orange” is the painting of a surgically exposed side of a store. Composed of modulated tones of orange colliding with a diagonal green and yellow slash, it features the typical markings of a classic abstract expressionist work, but Mitchnick keeps the context of the building by depicting the surrounding light and air of the city. “Big Burn” is a triumphant exploration of the remains of a home that, in its abandoned state, is slowly rotting and returning to the earth. Exposed rafters, plaster lath and crumbling foundation are astonishingly caressed into a derelict geometry that made Mitchnick blurt, “I felt like I was composing a symphony!” It is triumphant painting that in itself is a marvelous history lesson.

Nancy Mitchnick,” Big Burn”, Oil Painting, 129 x 59, 2006-20016

Each of the house paintings has a complexly charged presence. “Buffalo Street” is of the house in which Mitchnick grew up, and while it was in its last stages of devolution, Mitchnick’s painting still captures what seems a classical bearing, with its gabled roof and three-windowed dormer still erect and proud, and still evincing the colors that it once wore. It is difficult to imagine Mitchnick’s mindset when revisiting and painting this moment of her life and prompts the question of whether this is an elegy for the Buffalo Street house or an objective portrait.

Nancy Mitchnick, “Buffalo Street”, Oil Painting, 99 x 88, 2008-09

One of the most interesting aspects of Mitchnick’s work is the lesson that she teaches with each composition, which is that it takes a long look to realize a painting. Her latest pieces, “Night Heron” and “White Front,” seem almost recklessly whimsical compared to the disciplined, graphic painting of the abandoned houses. Populated with strange bits of ocean coral, odd mythic creatures (snakes, birds, turtles), and a Persian Princess, they are a gargantuan leap into another mind space. However, after one spends time with them, they gain traction, and their amazing palette of colors (throughout “Uncalibrated” her palette is symphonic) begins to tantalize, and an almost fairytale narrative gathers. It might be the story of a new Hamtramck or not, but it certainly signifies another trajectory for Nancy Mitchnick’s painting to mine.

Nancy Mitchnick,”Night Heron”, Oil Painting 77 x 111 – 2016

“Uncalibrated” will be at MOCAD until Sunday, July 31, 2016.