The Bob Boxes at the College for Creative Studies and the Valade Family Gallery

Ray Johnson, Installation – All images courtesy of Robert Hensleigh

There is a remarkable exhibition at the College for Creative Studies’ Valade Gallery and the subject, Ray Johnson, has haunted me for years. I thought this obsession was because he was a Finnish kinsman with similar, exotic ethnic roots in the Copper Country of Northern Michigan, or maybe because a seminal figure of Detroit art and culture, Gilbert Silverman, famed for his iconic collection of Fluxus art, was his close friend and became his lifelong patron. Of course the great documentary film about Johnson’s life and death, “How to Draw a Bunny” (a must see for anyone interested in Johnson’s artistic strategies), was also instrumental in creating his haunting identity. I thought maybe my fascination with Johnson was that he was a Detroiter who went to Cass Technical High School and then attended the unique and ultimate, progressive Black Mountain College, where the American avant-garde art was born, and where my own poet-model, Charles Olson, taught. While there in the vital Post WWll years Johnson engaged with John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Elaine and Willem de Kooning, Josef and Anni Albers, Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Buckminster Fuller, Franz Kline, Jacob Lawrence, Cy Twombly, Fracine du Plessix Gray, and many other art world lights.

But yesterday, curious about his local roots, I went to his childhood home on Quincy Street in Detroit and astonishingly discovered I was born directly behind his house on Holmur Street, the year he left for Black Mountain College. We discovered that my sister went to school with him.

None of this means a thing of course unless you’re Ray Johnson. And then it means everything, because if anything Johnson is about relationships: between people, objects, words, colliding and collaging (his basic gesture as an artist) or putting things together.

Johnson, often referred to as “the most famous unknown artist in America,” in addition to running with the New York School of famous painters, poets, and composers, spent years developing a network of relationships in the art world via that most democratic of institutions, the United States Postal Service. He basically created the New York Correspondance School (a play on the New York School of Abstract Expressionists and pun on creative movement of his art) and the phenomenon of “mail art” as a way of circumventing the capitalist art market of collectors, galleries, curators, and museums, creating a direct and intimate communication between artists. Using his own very finely crafted collage techniques and a complex personal iconography (rabbits, strange silhouetted portraiture of famous movie stars and artists, homoerotica, spinning on complex language games and puns), he created a network that sent out small-scale art works composed of drawings, photos, and cut-out texts from magazines of movie stars, product packaging, found objects, and ultimately whatever was part of the visual surface of post war popular culture that he swam in.

In the most significant aspect of Johnson’s mail art project, he asked for additions and collaborations on his work, as well as others he had “sent out,” to redirect and create an alternative visual dialogue among chosen artists. Johnson’s interest in both Zen practices and chance operations (through his close friendship with composer John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham) played a central part of his artistic practice and even more significantly in his enigmatic philosophical vision and life practice. Ultimately the New York Correspondence School attracted thousands of participants becoming a global network that eventually lost its human connectedness, which perhaps prompted Johnson in 1973 to proclaim the New York Correspondence School dead.

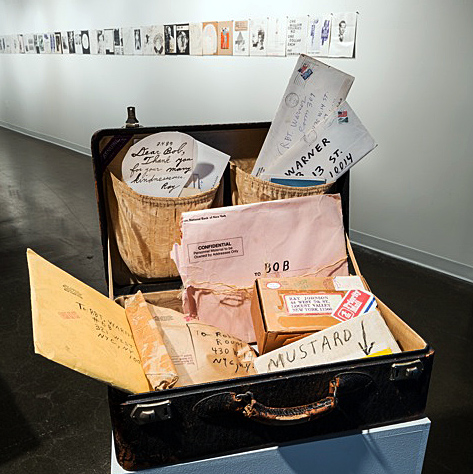

The exhibition at the Valade Gallery, The Bob Boxes, is the result of one particular mail art relationship that Johnson had with artist/collagist, Robert Warner. From 1988 until Johnson’s death in 1995, they maintained a correspondence exchanging mail and phone calls. At one point Johnson delivered thirteen boxes of various “mail art” he had created and collected, including found objects from everyday life and popular culture. (It is probable that the famous boxes of “assemblage” artist Joseph Cornell, whom Johnson had admired and befriended, inspired the “boxes” he created for Bob Warner, “The Bob Boxes.”)

Like Cage and, indeed the ultimate assemblage artist, Marcel Duchamp, Johnson was primarily interested in how chance encounters, between people, objects, or words, created new sets of possibilities or connections, or extended the possibilities for making meaning out of the world. He wasn’t interested in a singular system, visual, linguistic or cinematic, but any kind of “relationship” between things that prompted a vital often satirical critique. He referred to his small collages as “moticos” (an anagram for osmotic), created to stimulate or inspire connective tissue in everyday life. In a very real sense then there was no separation between Johnson’s art and life, and his seamless playful landscape provoked many to call him a Neo-Dada artist, a surrealist, which of course he rejected as just one more effort to classify him.

The Valade Gallery’s exhibition is then really a performance of Bob Warner’s “unpacking” of the 13 boxes that Johnson gave him. Placed on tables, the contents of the boxes — Warner’s humorous title for the exhibition is “Tables of Content” — have been distributed, and the results on each table are a tsunami of the flotsam and jetsam of the American visual landscape that Johnson assembled for Warner and us, providing a ready-made mail art kit for our visual challenge.

In addition to the “Tables of Content,” there are three vitrines containing early photographs from Johnson’s life in Detroit, including some wonderful drawings that he made while at Cass Technical High School. There are also seven hours of video — ”The Ray Johnson Videos” made by Nicholas Maravel — of Johnson talking about his work and generally performing himself for the camera.

Amazingly “The Bob Boxes” is the first exhibition of Ray Johnson in his hometown of Detroit for over forty years, and the Valade Gallery’s curator, Jonathan Rajewski, has provided a fine context and perspective on the work of one of the most enigmatic artists of the 20th century.

College for Creative Studies

A.Alfred Taubman Center for Design Education

The Valade Family Gallery 460 W.Baltimore Detroit, MI 48202

Gallery Hours: Wednesday-Saturday, 12 to 5 p.m.