Detroit Artist Tiff Massey Mounts an Exhibition: “Seven Mile and Livernois” at the Detroit Institute of Art

Tiff Massey, Installation image, Courtesy of DAR, 2024

Museums are often risk-averse institutions, choosing their curatorial offerings with an eye to what is safe and canonical. The Detroit Institute of Art has made a provocative and unexpected choice with its just-opened exhibition of Detroit-based sculptor and community activist Tiff Massey. “Seven Mile and Livernois,” as this year-long exhibition is called, places the artist’s practice squarely in the neighborhood where she grew up while also acknowledging her ties to art history, and in particular to artists whose works in the DIA’s collection shaped her childhood experience.

Massey is the youngest artist to be chosen for a museum exhibition at the DIA, as well as the first Black woman to earn an MFA in metalsmithing from the Cranbrook Academy of Art. The artworks, 11 in all, range from a piece, Facet, that she created in 2010 when she was still a student at Cranbrook, to 4 recent artworks commissioned by the DIA. (The museum provided funds for fabrication, though the artist retains ownership.)

Tiff Massey, Whatupdoe (part 1), 2024, stainless steel, photo K.A. Letts

As we enter the exhibition, a delicate swag of metal chain is draped high across a deep blue wall. Through the door into the next gallery, however, we see that this chain is connected to a much longer one that, as it grows in size, goes from ornament to architecture. At its midpoint, individual components reach beyond head-high and we simultaneously shrink from adult to child size and perhaps smaller as we measure our bodies against these monumental links. It is a through-the-looking-glass experience.

The chain, entitled WhatupDoe, is intended by the artist as a love letter to her spiritual community in Detroit and beyond. She celebrates her affection for the city, for its hair salons, fashion boutiques, and coffee shops, its hip hop artists and hair weaves, in the sculptures that extend throughout the exhibition. In a nearby wall title for an older piece, I Got Bricks (2014), Massey directly addresses her audience, “Detroit, I’m designing for us, so we can see ourselves …This represents us building something together.”

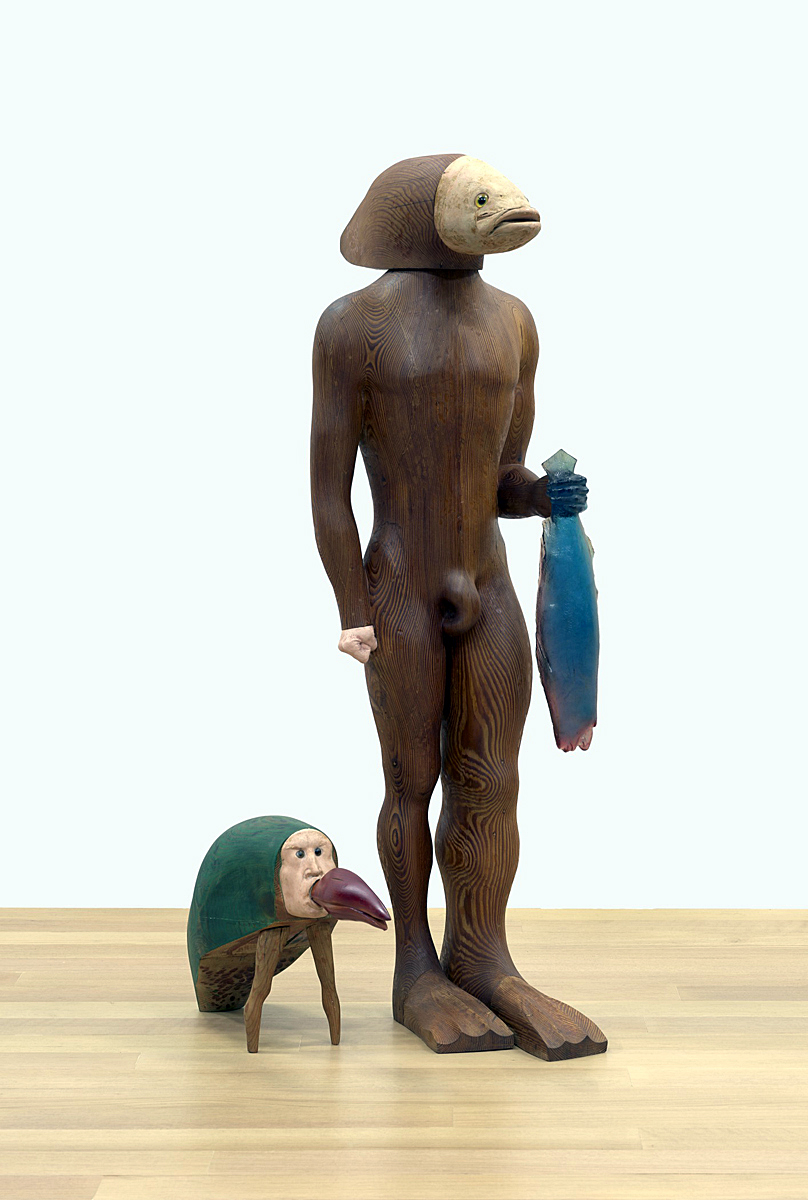

Tiff Massey, I Remember Way Back When, 2023, stained wood, photo K.A. Letts

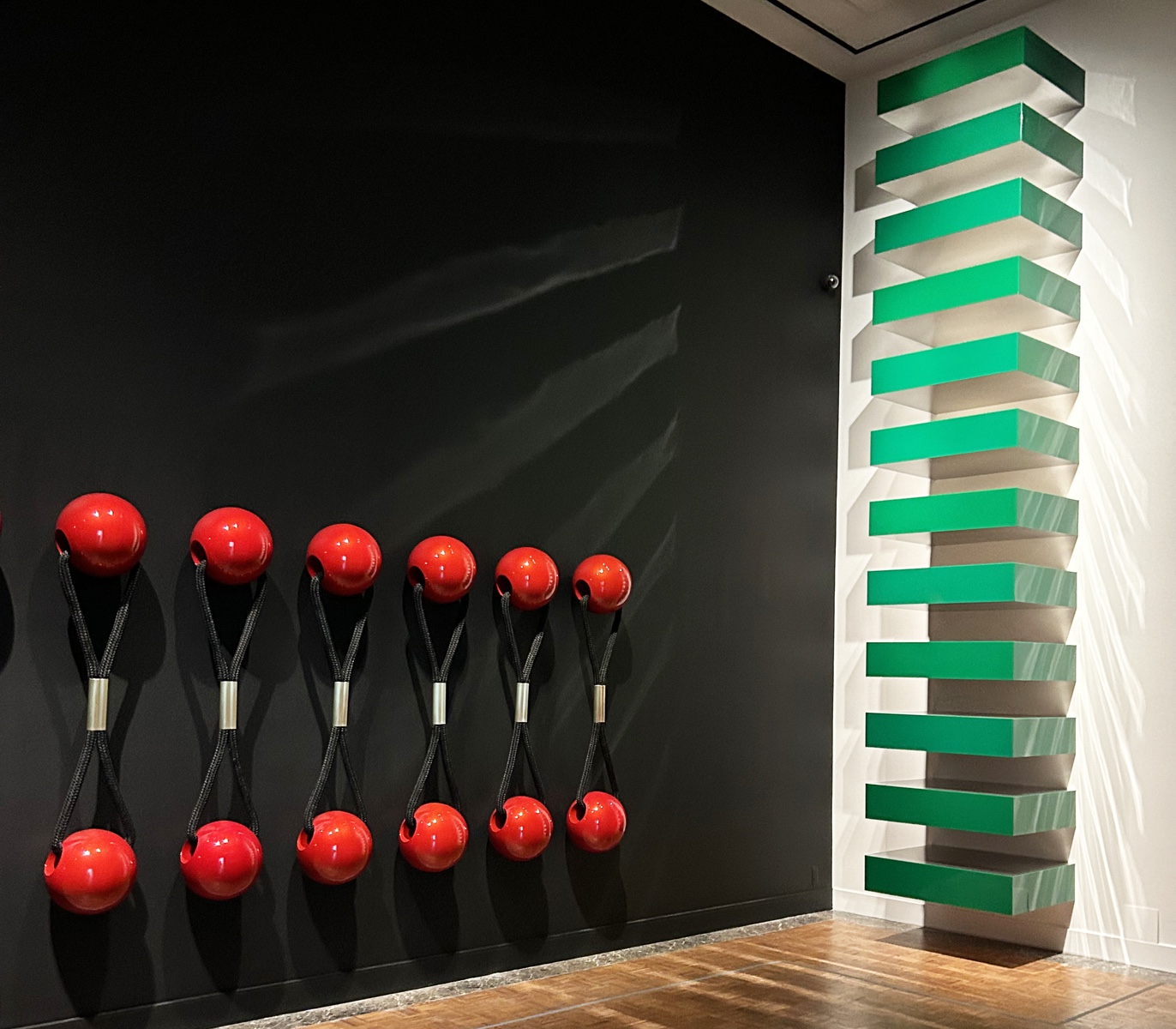

Massey’s intense emotional involvement with her social connections, friends and family is balanced by her acknowledgement of her early art education. As the artist developed plans for the exhibition with Juana Williams and Katie Pfohl, Associate Curators of Contemporary Art, she chose a couple of artworks from the DIA’s collection that hold special resonance for her: they are now displayed in the galleries along with her own work. She draws a particularly interesting comparison between her art practice and Stack, a minimalist sculpture by Donald Judd. In a recent interview in Detroit Cultural she says, “I chose Donald Judd because I remember this piece specifically from when I was a kid and my mom would take me to all of these institutions.” Stack, narrow and tall, climbs militantly up the wall of the gallery, a lacquered green tower of rectangles. In response, Massey has created Baby Bling, an adjacent, long row of objects that reference the hair ties she wore as a child. Made of enormous red metal beads, woven rope and brass, their horizontal orientation implies movement outward, toward caring and community.

Stack by Donald Judd (r.) 1969, plexiglass and stainless steel on the right. Tiff Massey, Baby Bling (detail, l.) installation on the left), photo K.A. Letts

Themes of adornment run through the exhibition, rituals involving hair being especially prominent. Across the gallery from Baby Bling we find I Remember Way Back When. Eleven outsize scarlet replicas of Snap-Tight Kiddie Barrettes recall the 1980s when little girls’ hair was carefully dressed by grandmas, mothers, and aunties. And at the end of the gallery, there is an enormous, wall-size homage to the elegant and exuberant hair weave, in ombre shades of green and seemingly endless in its shapes and patterns.

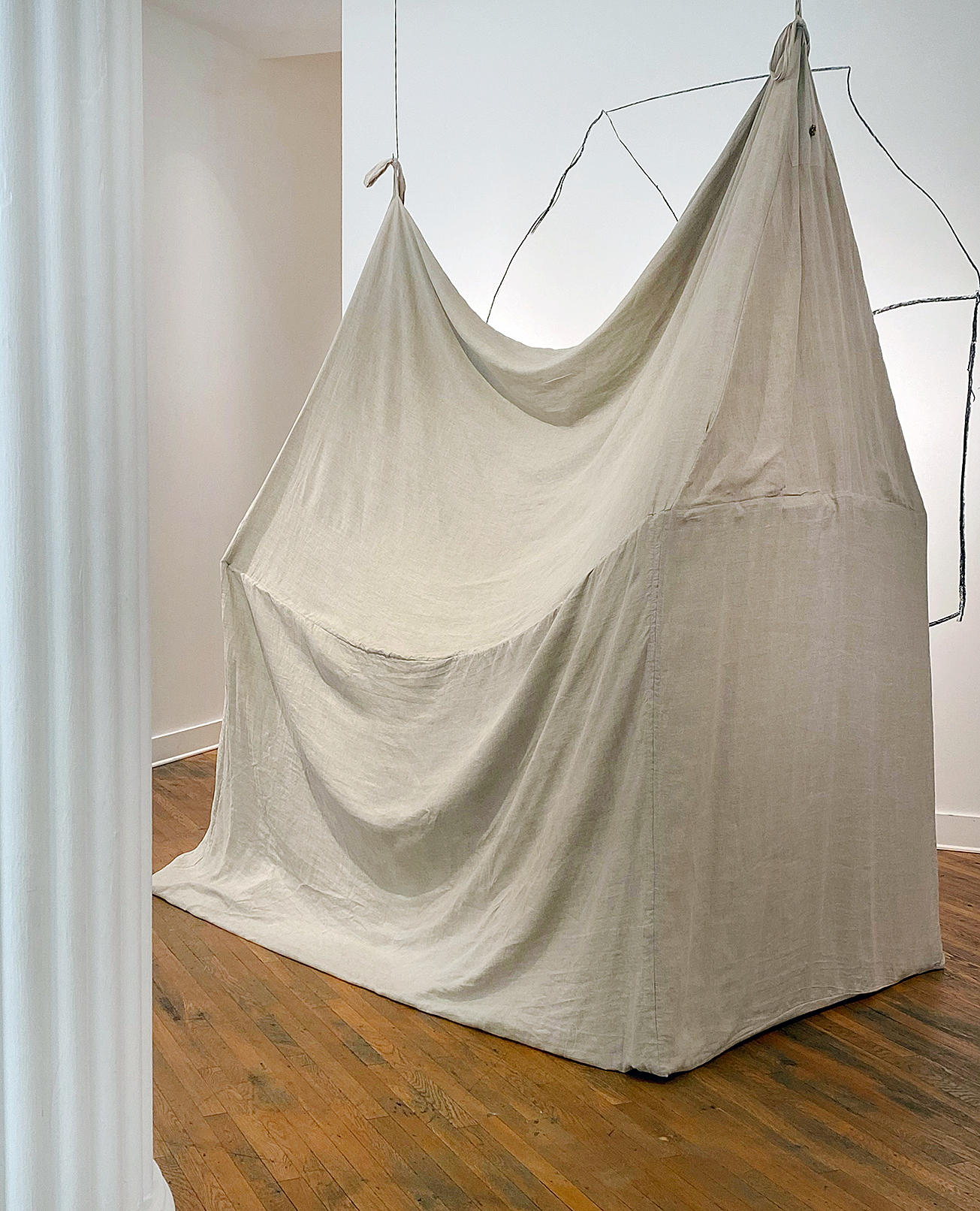

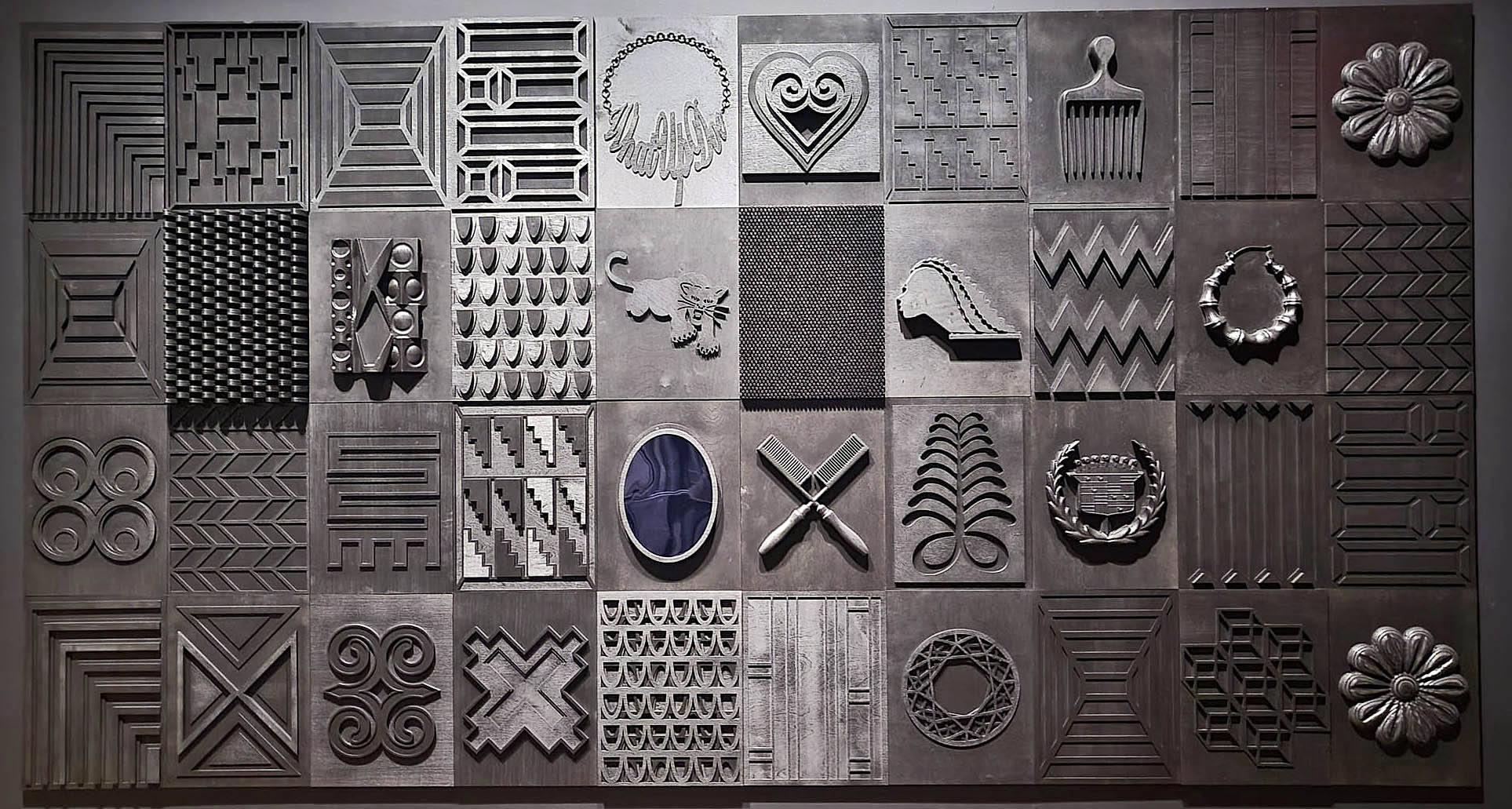

Tiff Massey, Quilt Code 6, Assmbledge, Detroit Institute of Arts, 2024

The other artwork with which Massey has chosen to pair her work is Louise Nevelson’s Homage to the World. The correspondences between this wall relief and Massey’s Quilt Code 6 are straightforward. As the artist developed plans for the exhibition with Juana Williams and Katie Pfohl, Associate Curators of Contemporary Art, she chose a couple of artworks from the DIA’s collection that hold special resonance for her; they are now displayed in the galleries along with her own work. ”Nevelson’s relief derives its power from the accretion of randomly found scraps into a massive wall of chunky wood pieces in sooty black; Quilt Code 6, by contrast, is finer and more literary, composed of carefully curated symbols and signs. As the name suggests, this piece shares characteristics with the American story quilt, a folk art fiber genre used to great effect by Faith Ringgold.

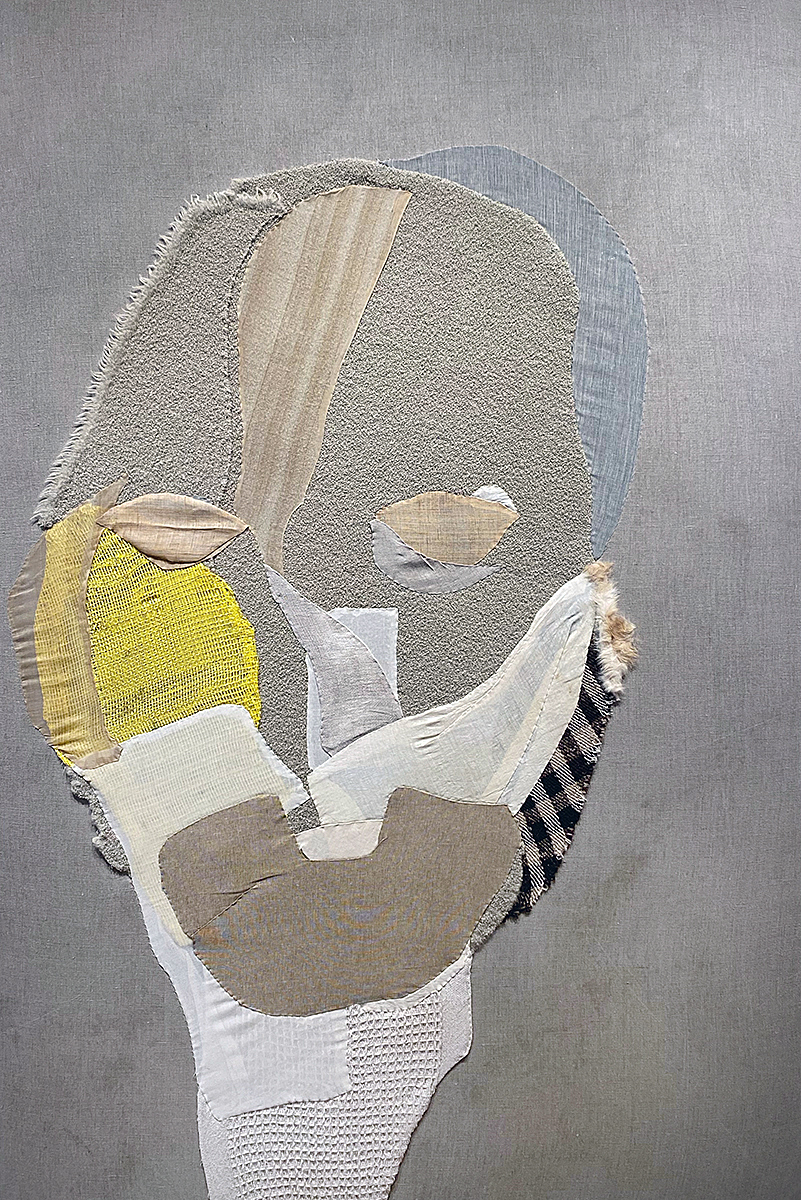

Tiff Massey, 39 Reasons I am not Playing, 2018, brass, photo K.A. Letts

In this exhibition, Massey both speaks for and to her community; she is fluent in the language of the hood and of the academy as she advocates for her city: “We’re a UNESCO city of design, and I’ve been talking about this in every interview but I don’t think we’re taking that designation seriously enough, and so to me it’s like how can I bring these elements and make sure that we have highly curated, beautiful spaces in the hood too.”

Massey demonstrates her commitment to her city and her people in “Seven Mile and Livernois.” It seems only fair, at least to this writer, that the DIA should take this opportunity to reciprocate by acquiring one of her public artworks for their permanent collection.

Tiff Massey, Whatupdoe, Stainless Steel, 2014, image courtesy DIA.

Tiff Massey’s exhibition, “Seven Mile and Livernois“, at the Detroit Institute of Art, is on display through May 11, 2025.