Kara Elizabeth Walker is an African American painter, silhouettist, and print-maker, who explores race, gender, sexuality, violence, and identity in her work. This exhibition is Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War.

Kara Walker, Installation image, courtesy of Toledo Museum of Art

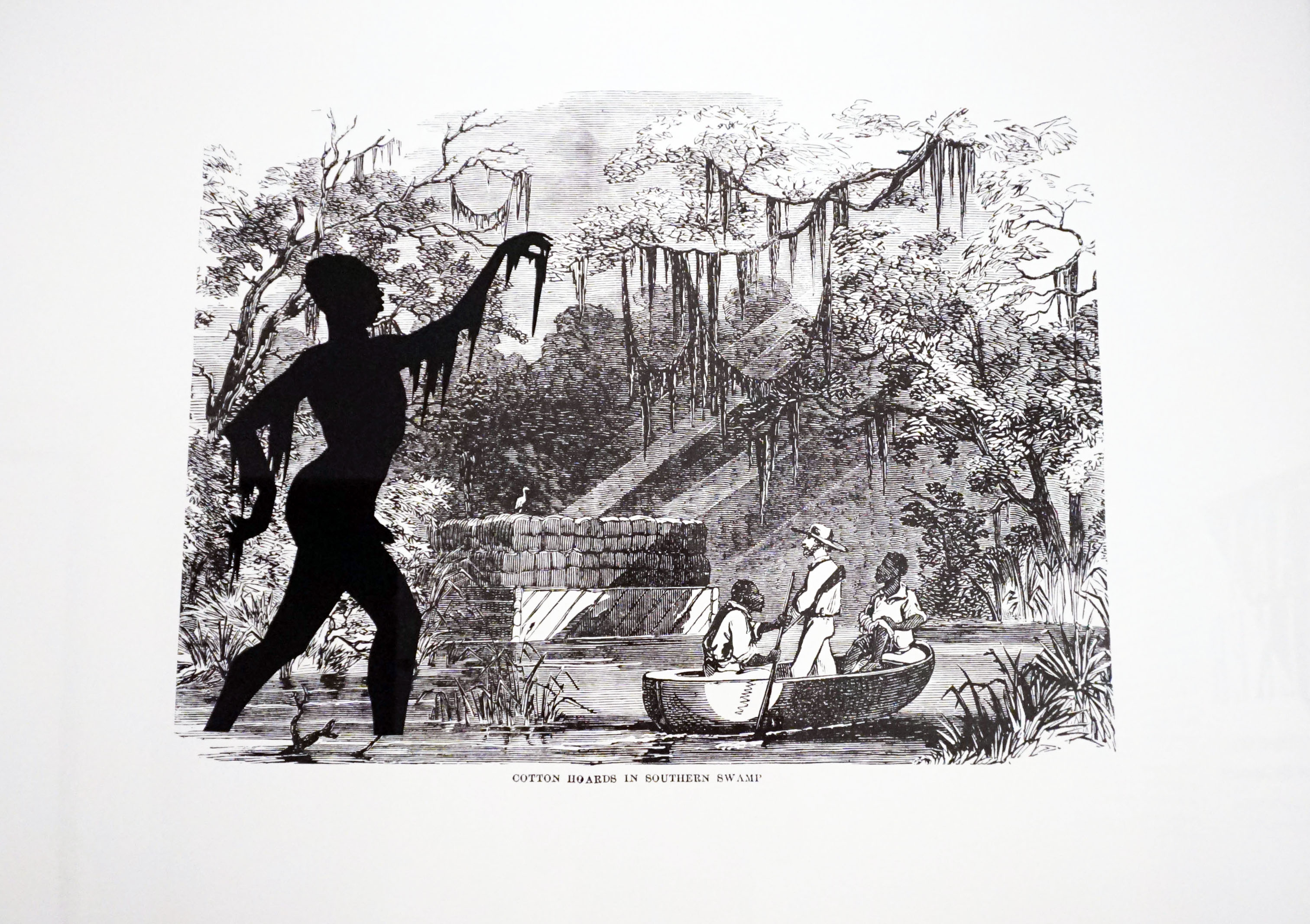

In 1866, the magazine Harpers Weekly published its Pictorial History of the Civil War, a hulking two-volume set which anthologized its prior five years of war reportage, replete with over a thousand illustrative woodcuts. American artist Kara Walker, known for her unsettling and often violent depictions of the antebellum South, “annotates” fifteen illustrations from the series by superimposing silkscreened silhouettes atop the unfolding dramas depicted in the original woodcuts, interrupting the narrative and re-contextualizing the images.

On view at the Toledo Museum of Art until October 22, this small but worthwhile exhibition features all fifteen silkscreens from Walker’s Annotated Pictorial History of the Civil War (2005), newly acquired by the TMA. There’s a helpful curatorial statement on the wall introducing the series, but from that point onward, viewers are just given the title of each work, so each image must be confronted on its own terms. Furthermore, they’re intentionally displayed without any obvious beginning or ending point, subverting any chronological narrative structure.

Tara Walker, Installation image, courtesy of Toledo Museum of Art

Walker’s calculated use of the silhouette harkens back to the antebellum-era popularity of the silhouette portrait in genteel society. But the silhouette is also loaded with associations of physiognomy; Walker’s silhouettes typically confront 19th century racial stereotypes though heightened exaggeration, caricaturing the caricature. Her silhouetted forms and figures also conscientiously reference Rorschach tests, the interpretations of which are fluid and in which there’s continual interplay between positive and negative space. In these lithographs, this interplay is dramatically heightened since the negative space consists of dramatically enlarged images from Harper’s Pictorial History.

Here, Kara Walker combines her art with characteristic wit and verbal irony; her “annotations” in this case are the silhouetted figures which place in the foreground that which was marginalized in Harpers–of the Pictorial History’s 1,000+ illustrations, just over a dozen contained any African-Americans, and only three images referenced slavery (possibly more, depending on what constitutes as a reference). Yet Walker’s annotations do the exact opposite of what we would expect of a marginal note, confounding, rather than enhancing, the narrative of the original woodcuts. Her figures sometimes mask out the entirety of the original subject. Other times, they re-shape the original narrative. Some even interact with, react to, or participate in the events portrayed.

Her annotations are allusive; neither side in the conflict is framed as having the moral high ground. In one instance, a silhouette seems brutally torn apart by the cannon-fire from the Union artillery in the original woodcut. In another, Union troops triumphantly march in parade-formation into Alexandria, Virginia, greeted by cheering figures, but Walker inserts figures of her own in the foreground; one shakes its fist at the sky in what might be exasperation or rage. Another seems to try to scurry away and hide.

Kara Walker, Cotton Hoards in Southern Swamp, courtesy of Toledo Museum of Art

These images aren’t flippantly dismissive of the many lives that were indeed lost during the Civil War, rather, they challenge the visual narrative of the conflict as presented by Harpers. Some of its depictions of African-Americans (such as Cotton Hordes in a Southern Swamp) stoop to cruel and abusively dehumanizing caricature. This is especially disconcerting when weighed against the book’s claim in its preface (which appeared in both volumes) of authenticity and impartiality. For reference, incidentally, featured in this exhibit are an original copy of the 1866 Harpers text and a screen which allows us to compare Walker’s annotations with the original illustrations from which they derive.

One should enter this show ready to be unsettled and at times disoriented. Yet we can always confidently approach Kara Walker’s work assured that she’ll have synthesized both fine craftsmanship with a well-thought out concept, reminding us along the way of the sad ironies so tragically present in America’s history. And her work has continued relevance– competing political narratives vocalize ever more shrilly in print and electronic media, but Walker’s Annotated History suggests we not accept any unscrutinized narrative, de facto, as truth’s final word.

Toledo Museum of Art Through October 22, 2017