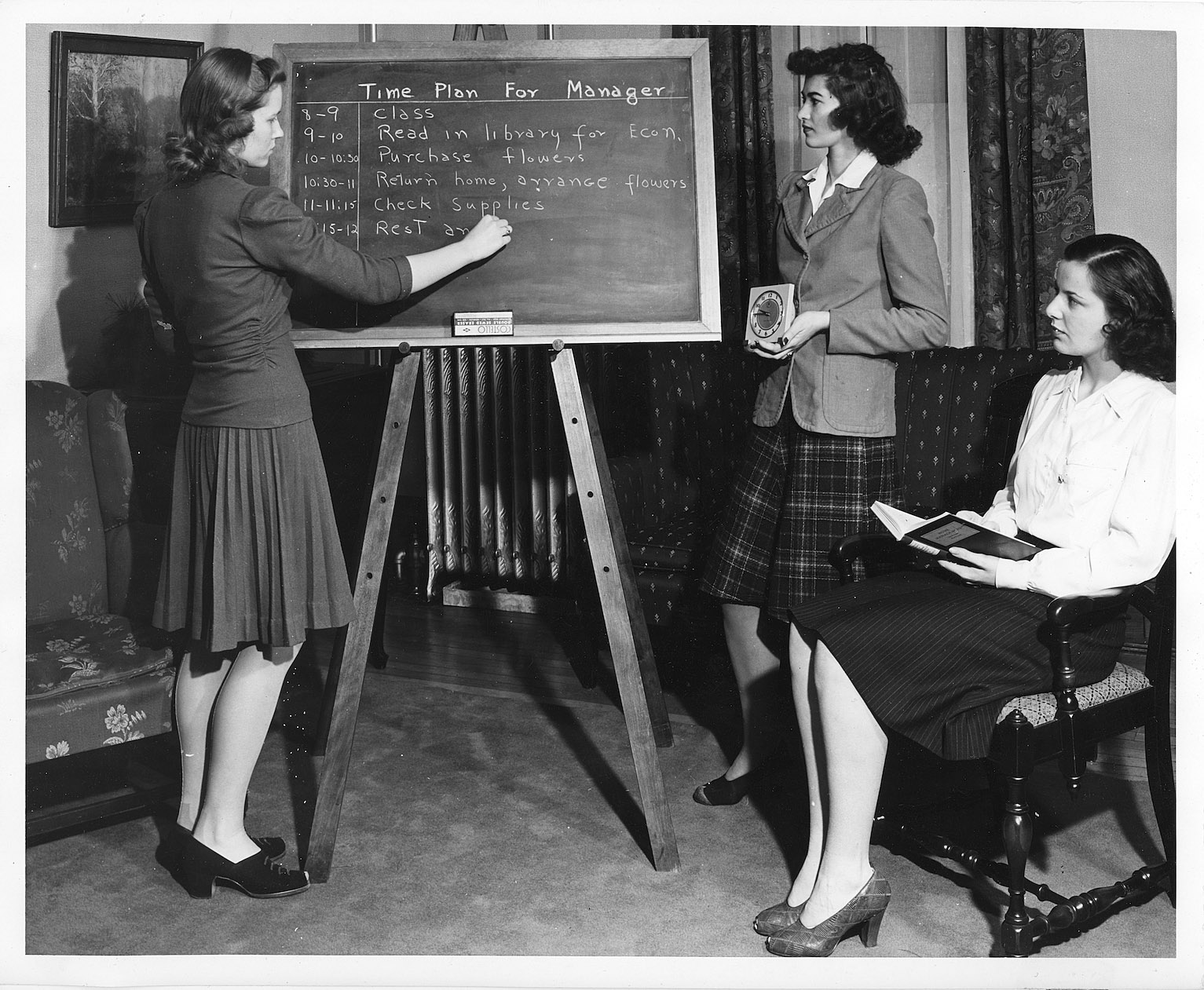

Doug Cannell: presents Learning Curves at the Stamelos Gallery Center, UofM Dearborn

Doug Cannell: Learning Curves, installation view.

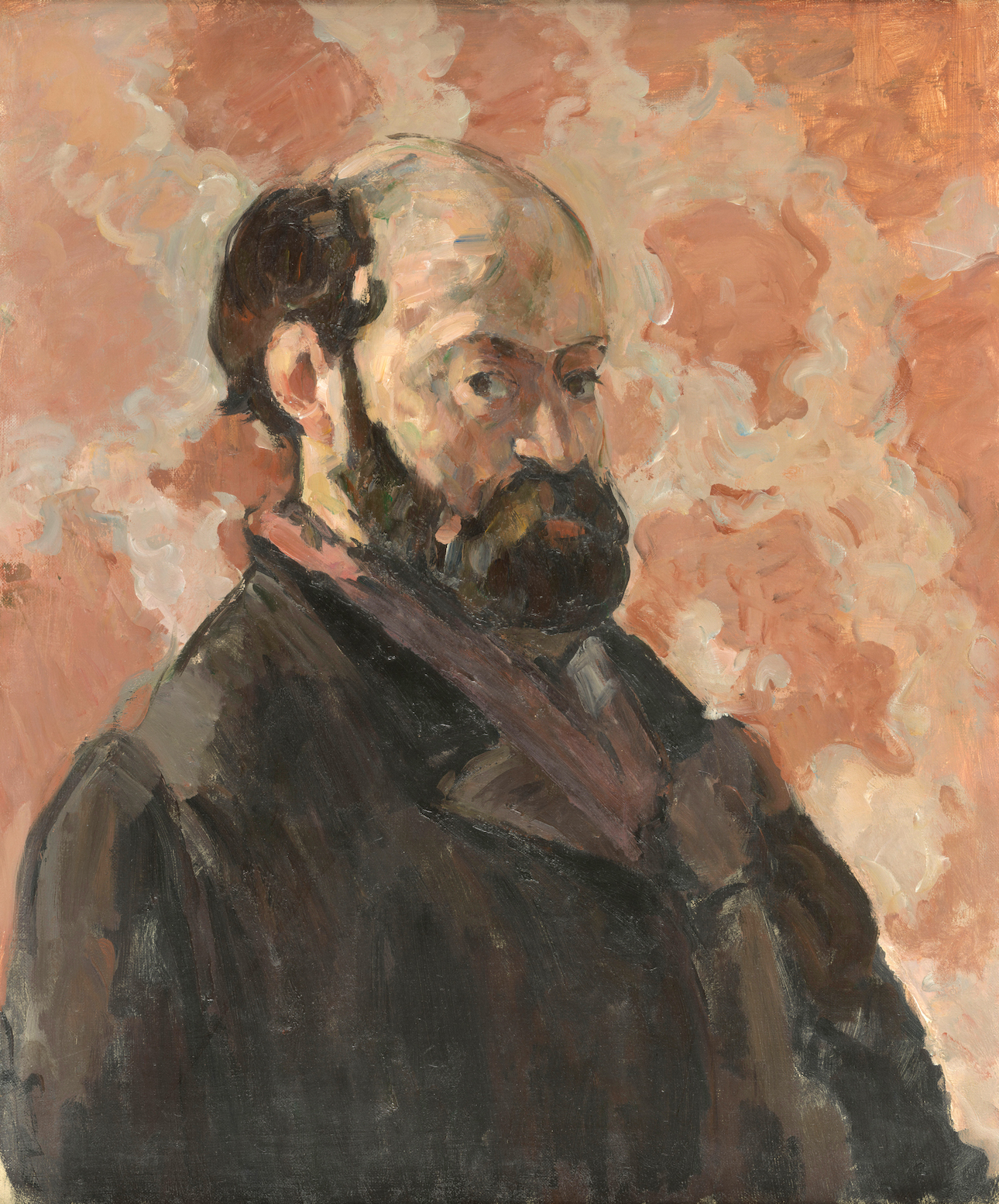

The inspirations behind Doug Cannell’s sculptures are many and varied. They range from jazz music, the movement of water, urban decay, font design, calligraphy, and more. He’s also deeply inspired by the textures of Detroit’s places and spaces, where he was born and raised, and much of his work blurs the boundaries between the organic and the industrial. “I buy my art supplies at scrapyards,” Doug Cannell writes, and “hardware stores and lumberyards.” Through December 10, the Stamelos Gallery Center (of the University of Michigan, Dearborn) presents Doug Cannell: Learning Curves, the artist’s most comprehensive exhibition to date.

Cannell mostly works with lumber and metal, exploring all the possibilities of the media, but always adhering to a truthful honesty to the material, never making metal or wood look like something it isn’t. Many of these works also draw on Cannell’s years of experience as a graphic designer, particularly the works which evoke different letters, alphabets, and typefaces. With some exceptions (like his series The Language of Bodies), the overwhelming majority of his works are abstract. All his work adheres to careful attention to craftmanship and design.

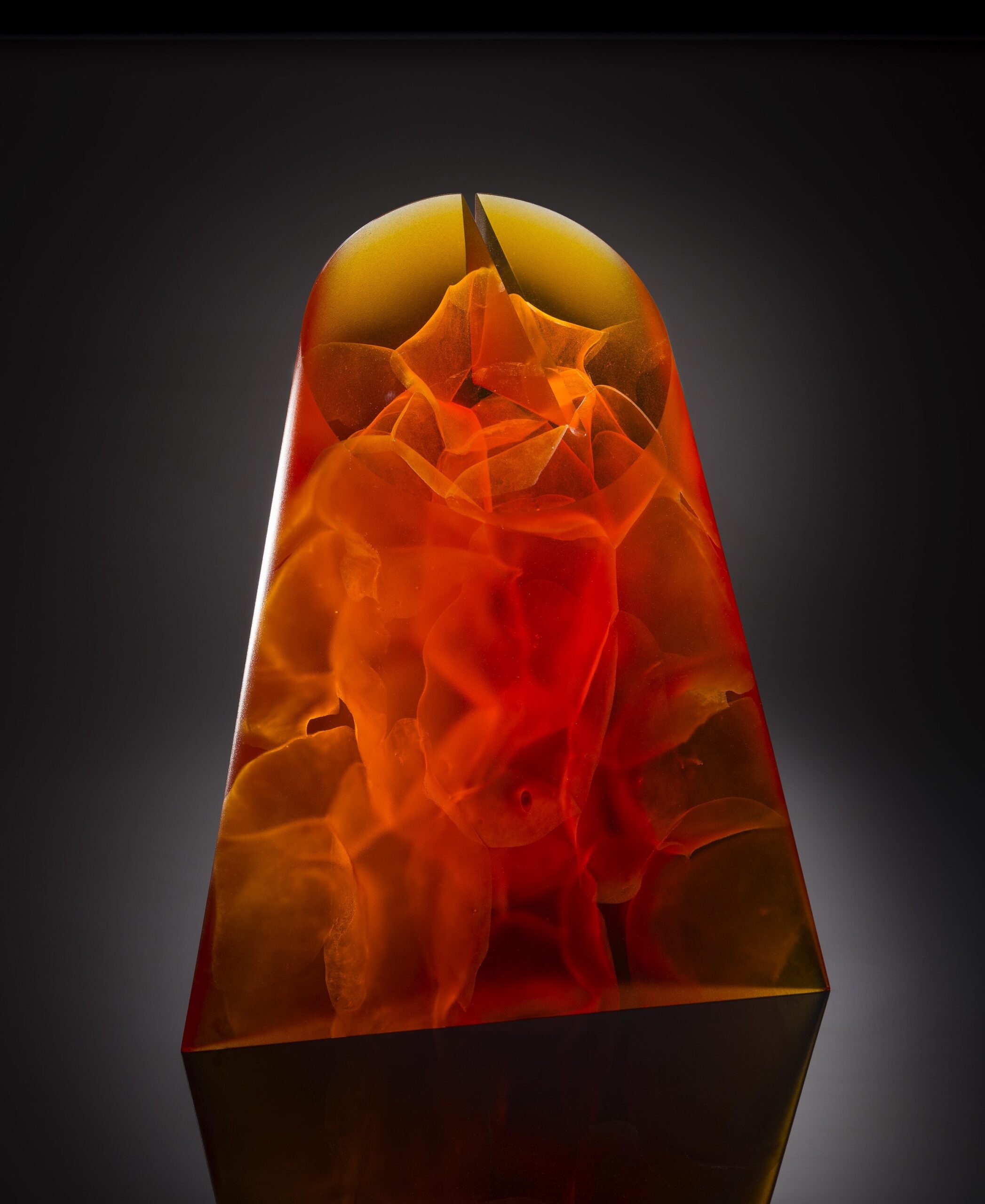

Learning Curves features multiple series of works created over the span of ten years, but gives prominence to two new bodies of work. The Enso and Beyond is sourced in the meditative Zen practice of creating an enso, a circle made with one continuous stroke of a calligraphy brush. Cannell transposes the enso into three dimensions, playing with its minimalist form in a series of circular wooden sculptures. Some of these are almost literal 3D interpretations of an enso, while others are more indirect, suggestive of calligraphic linework in a more general sense. Speaking of these works, Cannell says, “I liked the idea that it’s not so much about the finished product, but it’s about the experience of making the artwork. It’s a meditative moment.”

Doug Cannell: Learning Curves, installation view.

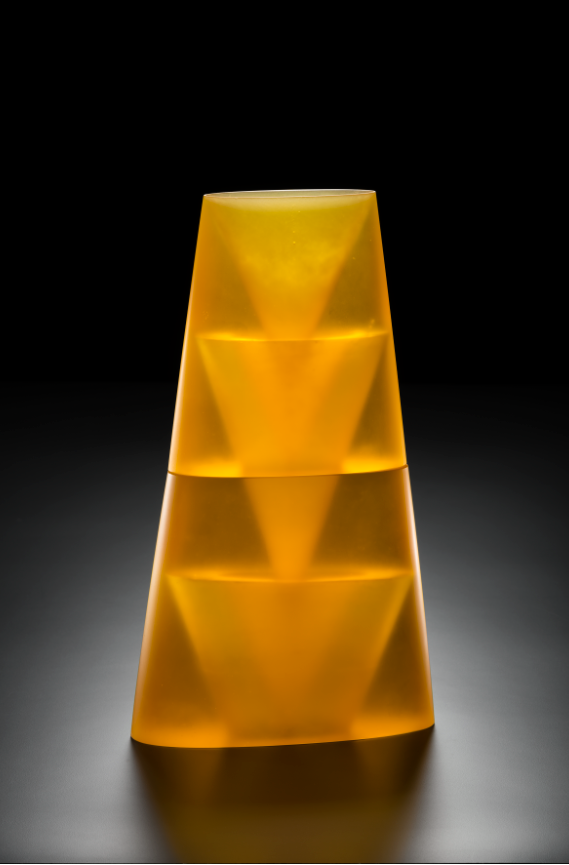

The other new body of work on view is sourced in Cannell’s experience as a graphic designer, a field which gave him an immense appreciation for the capacity of various fonts and typefaces to enhance the meanings of words and to imbue words with nuance. In the series Letterforms, Cannell takes letters from various alphabets of the world, deconstructs them, and merges them together into sculptures that celebrate the language or the font on which they’re based. The forms are abstracted, but still recognizable, so viewers might recognize letters from the Thai alphabet, or Korean, Arabic, or Hebrew. It’s a series in wood which draws attention to the pure form of words without regard for their literal sounds or meanings.

Filling about half of the gallery space, these two recent bodies of work are displayed alongside selections of earlier works. One series is an expressive body of works which explores emotion and body language. The defensive postures the life-sized wooden figures assume are often suggestive of struggle. In using representational/figurative imagery, the series is an outlier in Cannell’s larger body of work, the rest of which is almost entirely abstract.

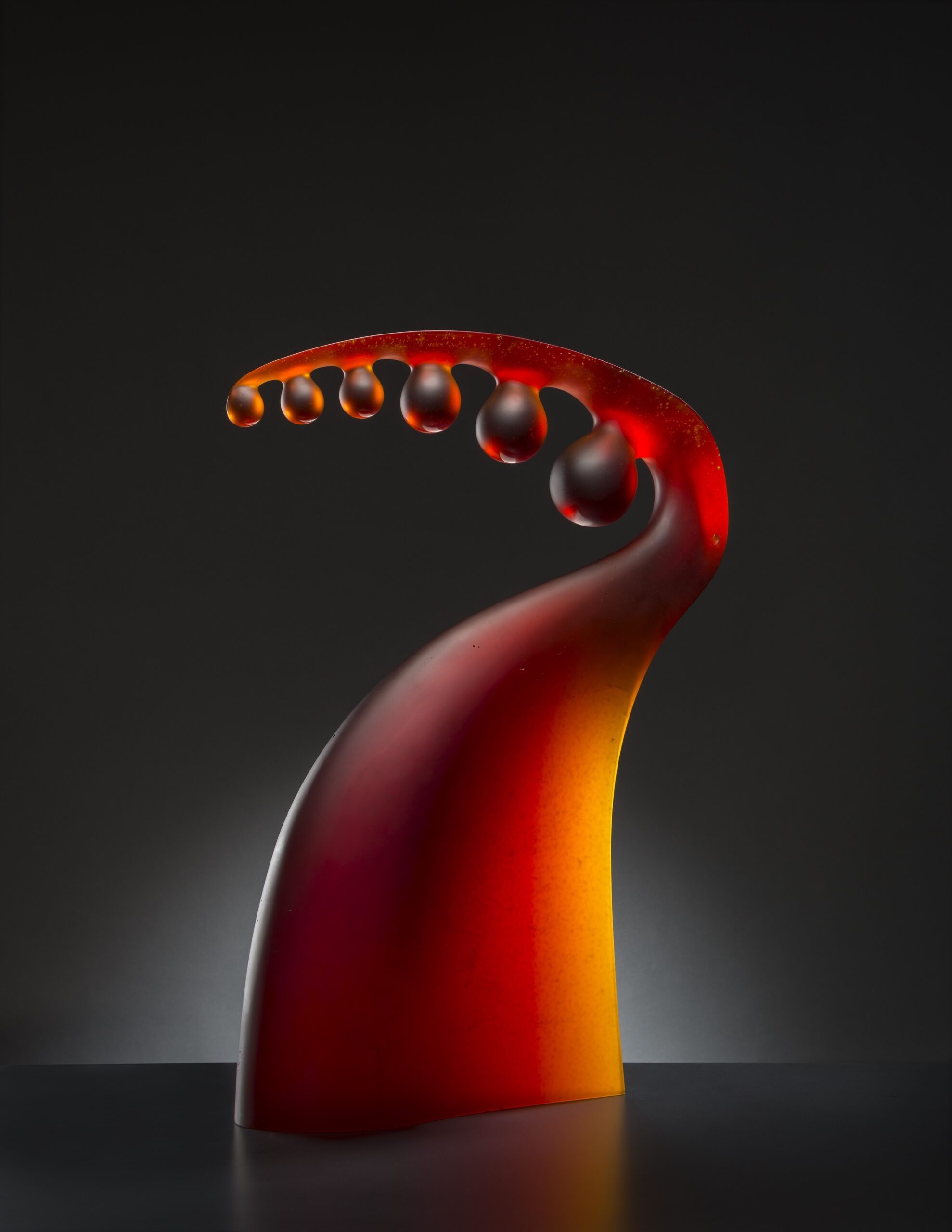

More typical (if its ok to say that about a body of work as relentlessly varied as this), are the abstract wooden sculptures of the series A Tree is a Wild Thing. Each of the emphatically organic forms in this series was created using rectangular boards of industrial lumber, which Cannell then worked until the wood attained a beauty more suggestive of its original source in nature.

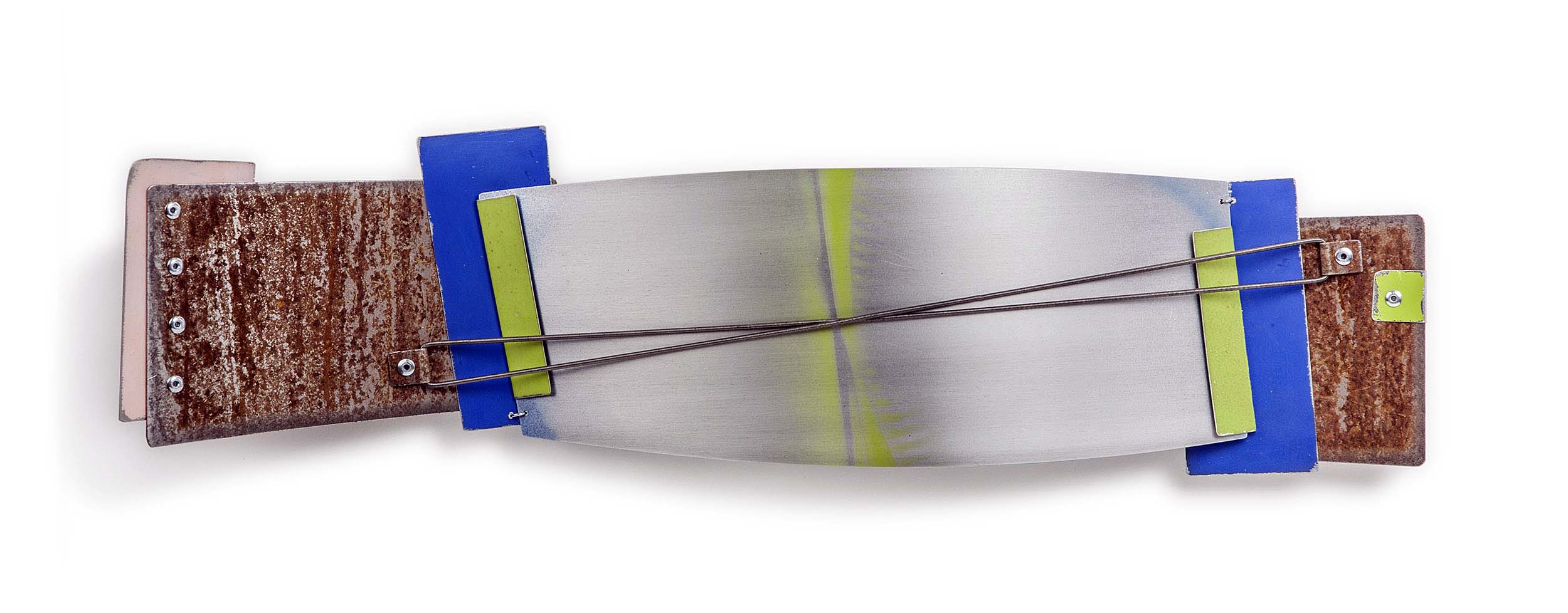

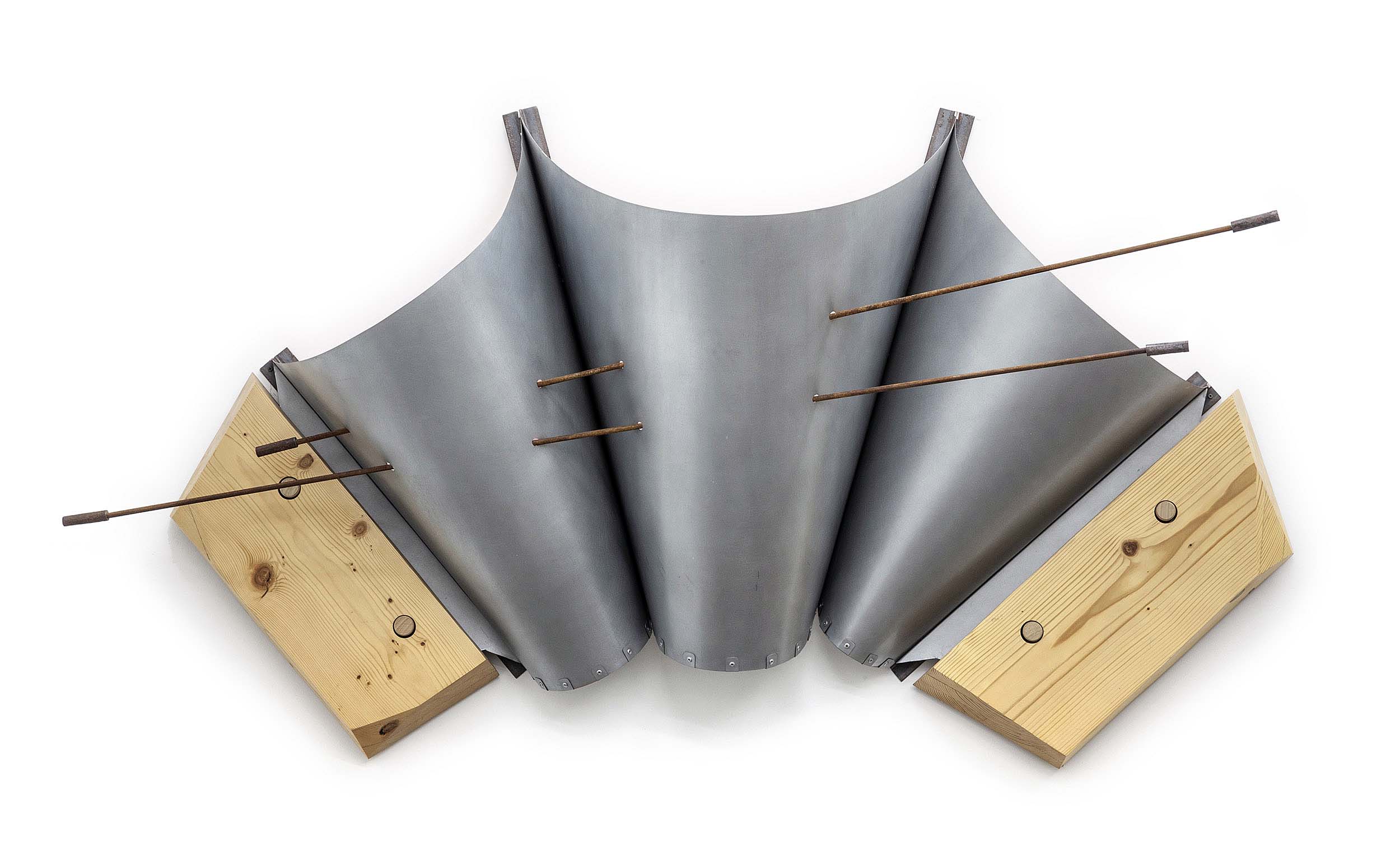

But Cannell’s work also explores the beauty and formal qualities of industrial materials, and the series Art and Invention is an exploration of the visual possibilities of steel and its decay. Often making use of repurposed, rusted steel, some of these wall-mounted sculptures seem like more polished and refined versions of the doggedly rugged industrial sculptures of Constructivist Vladimir Tatlin.

Arc Mentha, 2017 (28”x 8” x 4”), steel, aluminum, paint.

Thrump, 2016, (48’’x94’’x34’’), steel and wood

There seems to be a whimsicality and a playful quality to much of this work. It blurs boundaries between the organic and industrial…between craft and fine art. Regarding the inevitable categorization of his work into “series,” Cannell confesses that his goal is never to set out to create a series, and that a work in one set might just as easily fall into another. His work defiantly refuses simplistic categorization and easy labels, much like the places, spaces, and textures of Detroit itself.

Doug Cannell: Learning Curves, installation view.

Doug Cannell @ Stamelos Gallery Center, UofM Dearborn, through December 10, 2023.