Church: A Painter’s Pilgrimage

Church: A Painter’s Pilgrimage, currently on view at the Detroit Institute of Arts, presents a dazzling selection of works made by one of America’s most well-known and successful Nineteenth Century painters. Frederic Edwin Church is best known for highly rendered visions of manifest destiny- expansive, breathtaking views of the American west and South America. Church traded mainly in paintings of virgin land- land untampered with by humans (the people who had made their homes in such landscapes for millennia are mostly absent from Church’s paintings, save as the odd bit of picturesque window dressing). Land that was considered the God-given right of Church’s audience, described by the DIA as “white, Protestant, American.” One thing that A Painter’s Pilgrimage makes clear- through an excellent guide of subtly pointed remarks provided by the DIA- is how much the romance of that Nineteenth Century American, white, Protestant narrative is still with us, buried deep in our cultural bedrock.

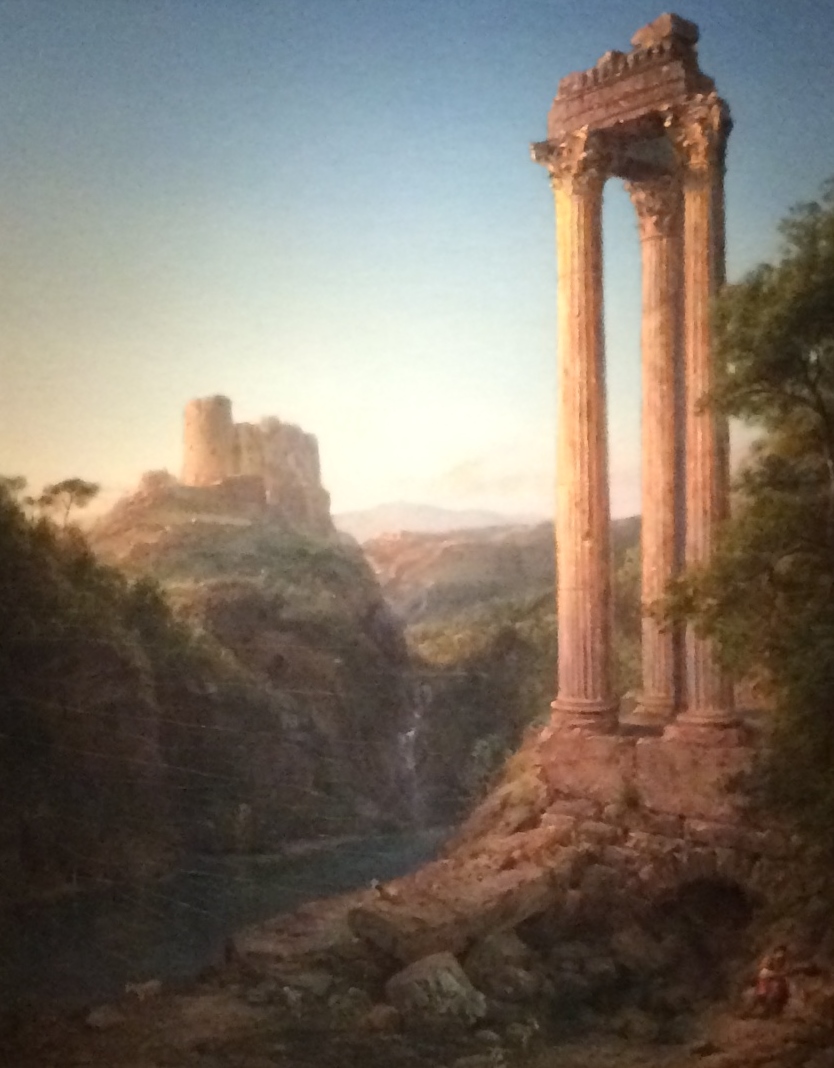

A Painter’s Pilgrimage showcases an unconventional body of work for Church- paintings made during a journey the artist took around the Middle East and the Mediterranean in the region then known as the Levant. Church rarely dealt with human history directly in his iconic American landscapes- in A Painter’s Pilgrimage, stately ruins and picturesque cityscapes layer over one another like condensed timelines of Western civilization’s cradles.

Frederic Church, Nature and Civilization, Sunrise in Syria, Oil on Canvas, 1874

Wandering the dimly lit galleries (necessary to protect the paintings) it’s difficult not to be swept away in the grandeur of Church’s vision- every single work is simply dazzling. Church was, first and foremost, a great painter. A devout Christian, he invested all his works with spiritually symbolic shifts in light, focus, and atmospheric cataclysm. His wildly billowing clouds, lurid red skies, and sublime scale speak to the greatness of his God’s creation. The visual rearrangement and condensing of human monuments that he engaged in while painting Middle Eastern landscapes speaks to the desires of the artist and his audience, who clearly felt a sense of ownership of this ancient landscape and how it ought to appear. The dreamy genre painting Al Ayn (The Fountain) combines various types of architecture from different places and eras to describe the arch of civilization’s rise and fall.

Frederic Church, The Fountain, Oil on Canvas, 1882

It also features human figures placed in the foreground, an unusual move for Church, but one that completes his romantic vision of the East. Al Ayn could be an illustration of the history of Orientalism- problematic as the image is, it’s so beautiful that one can’t help but be drawn in by it. This frisson persists throughout the show- how does one look at paintings that are so vested in the West’s destructive view of landscape and people, that are themselves posters for Colonialism, racism, manifest destiny, etc…. and yet are so intoxicatingly lovely?

Frederic Church, Erechtheum and The Parthenon Study, Oil on Paper, 1869-70

Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives is the stunner in a galaxy of stunners. Just beginning to get over Church’s grand but achingly overdone visions of Classical architecture (his Parthenon is so painstakingly rendered and devoid of the freshness of his smaller, on-site studies, which are sprinkled throughout the galleries like shimmering dewdrops, that it quickly gets exhausting to look at) an encounter with Jerusalem renews the eyes and stops the breath. It’s clear that this was probably the most significant site in the Middle East for Church- the epicenter of the Holy Land.

Frederic Church, Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives, Oil on Canvas, 1870

The painting is just what its title says- a view of the ancient walled city from atop the Mount of Olives, where twisted, gnarled trees reach toward the sky, symbolizing the suffering of Christ. The sublime distances roped into the view. The layers of light. The sunlit olive branches pulsating over the deep-shadowed valley. The pure, blinding light at the focal point- the Dome of the Rock at the city’s apex. Here, Church breaks atmospheric perspective- everything is far too sharply in focus for the distance, which increases the otherworldly feel of the view. The odd little comb of perfectly angled shadows of the row of columns to the right of the Dome. The dazzling tips of roiling storm clouds massing along the horizon- the vast, perfect lapis blue of the sky beyond. This is a genre painting that transcends genre- an enormous confection of kitsch that transcends its kitschiness. This is the paradox of Frederic Edwin Church- a painter with truly sublime vision and (for contemporary viewers) deeply problematic politics. That vision makes the seduction of those politics hard to resist. These paintings present a crystalline vision of my childhood daydreams of a vast, mythic, mysterious East. This strange familiarity suggests that Church’s vision- the vision of manifest destiny- is still with us. A Painter’s Pilgrimage is canny to that vision, and provides a great contextual, historical lesson in its making.

Frederic Edwin Church: A Painter’s Pilgrimage is on View at the Detroit Institute of Arts from October 22, 2017 through January 15, 2018