Installation, “Crucify my Flesh,” front gallery at David Klein, 2023, Detroit, MI, photo: P.D. Rearick

Spring, 2023 has been an eventful season for Detroit artist and photographer Ricky Weaver. Two exhibitions, one at David Klein’s downtown gallery entitled “Crucify My Flesh” began a survey of the artist’s recent work in March and is now followed by a companion show “Way Outta No Way“ at the Institute for the Humanities Gallery in Ann Arbor.

The series of seven large photographs in the main gallery at David Klein, Untitled, On the Mainline (Anthem), introduce Weaver’s highly charged subject: the vexed relationship between the Black female body and contemporary culture. The artist prefers to call the pictures “image-based objects trafficking in the grammar of black feminist futurity” rather than self-portraits. This strikes me as an evasion typical of her art practice, which simultaneously conceals and reveals. With this recent work, Weaver sets up a dynamic of approach/avoidance that persists throughout both exhibitions, at once attracting us while simultaneously holding us off.

Ricky Weaver, Untitled, On the Mainline, (Anthem) #9037, 2023, archival pigment print, 45” x 30,” ed. of 5 + 2 AP, photo: P.D. Rearick

Ricky Weaver, Untitled, On the Mainline (Anthem) #9084, 2023, archival pigment print, 45” x 30,” ed. Of 5 + 2 AP, photo: P.D. Rearick

Ricky Weaver, Untitled, On the Mainline (Anthem) #9084, 2023, archival pigment print, 45” x 30,” ed. Of 5 + 2 AP, photo: P.D. Rearick

The handsome images in Untitled, On the Mainline, (Anthem)are larger than life size and–oddly–cut off the subject from the neck up. The subdued color of the pictures emphasizes the velvety texture of the sitter’s skin, contrasted with the shiny lacquer of her nails. A delicate necklace helpfully names the subject as “Ricky” and Weaver pointedly focuses our attention on her elaborately manicured, gesturing hands, even as her body is swathed in liturgical black. The nails, beringed and extravagantly appliqued with Christian symbols, are talon-like. They signify both beauty and danger as they hint at meaning in some unknown sign language. Because the images are ranged around the gallery in a row, the impulse to read them as a coded narrative is almost irresistible. So we follow them around the room as the hands point to something outside the picture frame, as they clutch the fabric of her robe closed or hold it open, as a nail digs into her own breast. Without engaging in verbal exposition, Weaver suggests suffering, negation, devotion, refusal. The photographs in this series are an exercise in revealing and concealing, drawing in and pushing away. The religious imagery and text suggest a spiritual struggle inherent in her negotiation of race and gender in a surrounding society that both sexualizes and demeans. Weaver’s refusal to reveal herself is hence her declaration of autonomy.

Installation, “Crucify My Flesh,” back gallery at David Klein, 2023, Detroit, MI, photo: P.D. Rearick

In the second room at David Klein, Weaver positions herself squarely within a matriarchal family structure bounded at one end by her recently deceased grandmother and at the other by tender photographs of her daughters in private moments of caregiving. A series of five images, Untitled, I Sound Like Momma’N’Em (Care and Council), shows Weaver’s daughters in an intimate setting and positioned to suggest vulnerability. Once again, the hands are the point of focus, as they delicately braid and dress hair or merely lie quietly on bare skin. Faces are obscured either by the camera angle or –as in the case of image #9997–purposely obscured by a hat.

Ricky Weaver, Untitled, I Sound Like Momma N’Em (Care and Council), #9997, 2023, archival pigment print, 30” x 20,” ed. of 7 + 2 AP, photo: P.D. Rearick

The recent death of Weaver’s grandmother, a central figure in her upbringing, has engendered an installation that examines universal themes of death, Black historicity and the connection of the living to the departed. The center of the gallery is devoted to an obsidian-black glass circle on the floor which suggests an open grave. It is ringed by loose soil, with ritual lavender and prayer candles. The skyring portal, though, also serves as a looking glass for the living, reflecting quotidian corporeality in the face of nothingness. Two black mirrored images, Lay My Burdens Down 1 and 2, echo the dynamic of the floor installation and suggest death’s welcome escape from the burden of physical existence.

Installation, “Way Outta No Way,” 2023, University of Michigan Institute for the Humanities Gallery, Ann Arbor, MI, photo: K.A. Letts

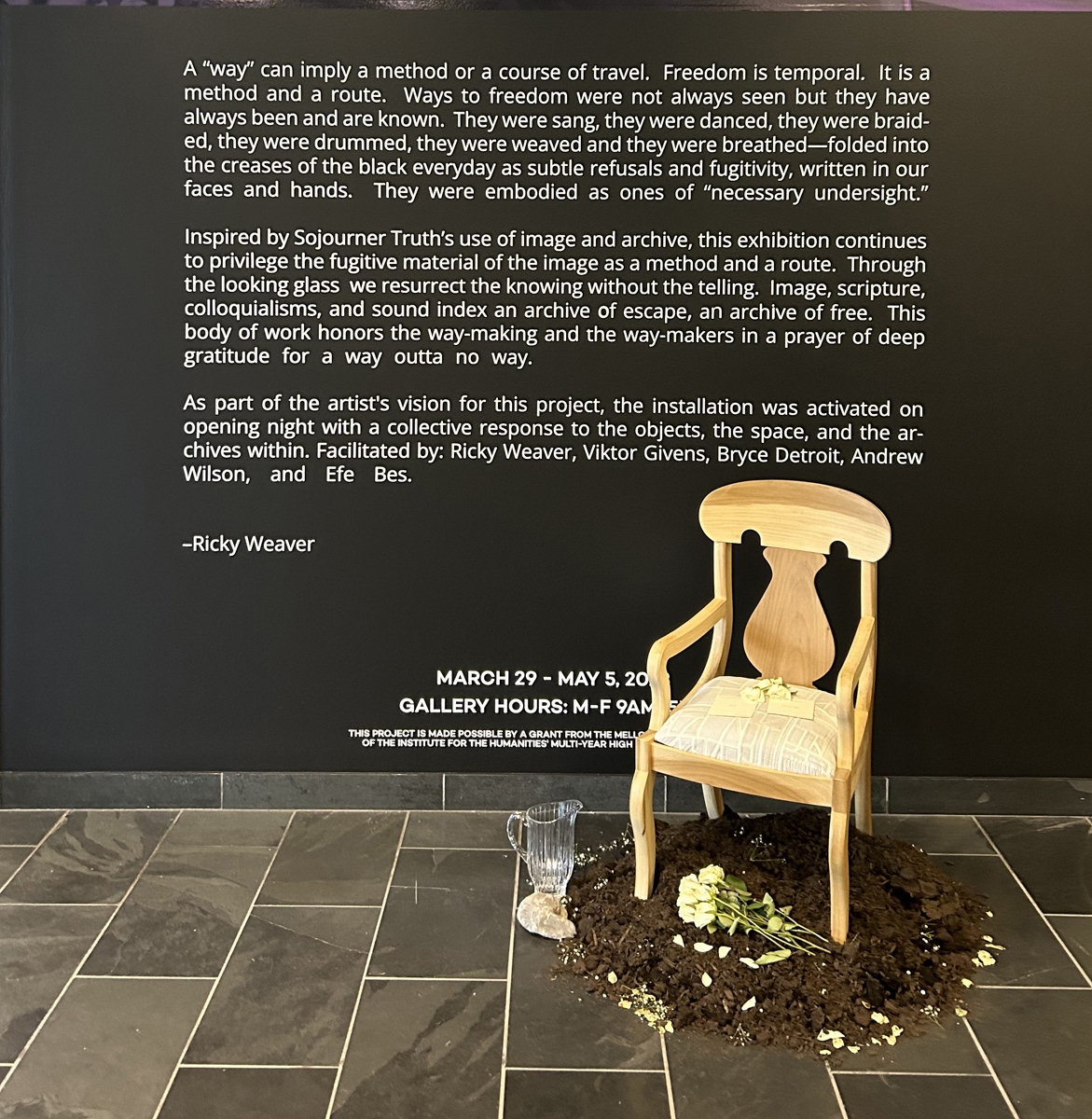

Moving on to the second exhibition, “Way Outta No Way” at the University of Michigan Institute for the Humanities Gallery, the black reflective image surrounded by soil reappears, now much larger and positioned in the center of the gallery, signifying secret knowledge and resistance. Weaver has moved from the intimate focus of “Crucify My Flesh” to the broader significance of the fugitive image in resisting historic oppression of Black people. The elements of a ritual that can only be guessed at by the uninitiated govern the placement of the objects in the gallery. Domestic furniture, flowers, dirt and water imply some cryptic, encoded body of knowledge. Or as Weaver says, “Ways to freedom were not always seen but they have always been and are known…This body of work honors the way-making and the way-makers in a prayer of deep gratitude for a way outta no way.”

Installation, “Way Outta No Way,” at the University of Michigan Institute for the Humanities Gallery, Ann Arbor, MI, photo: K.A. Letts

“Way Outta No Way” will be on view at the University of Michigan Institute for the Humanities Gallery in Ann Arbor until May 5. For more information on images from “Crucify my Flesh” go to https://www.dkgallery.com/exhibitions/91-ricky-weaver-crucify-my-flesh-detroit/