James Barnor: Accra/London – A Retrospective at The Detroit Institute of Arts

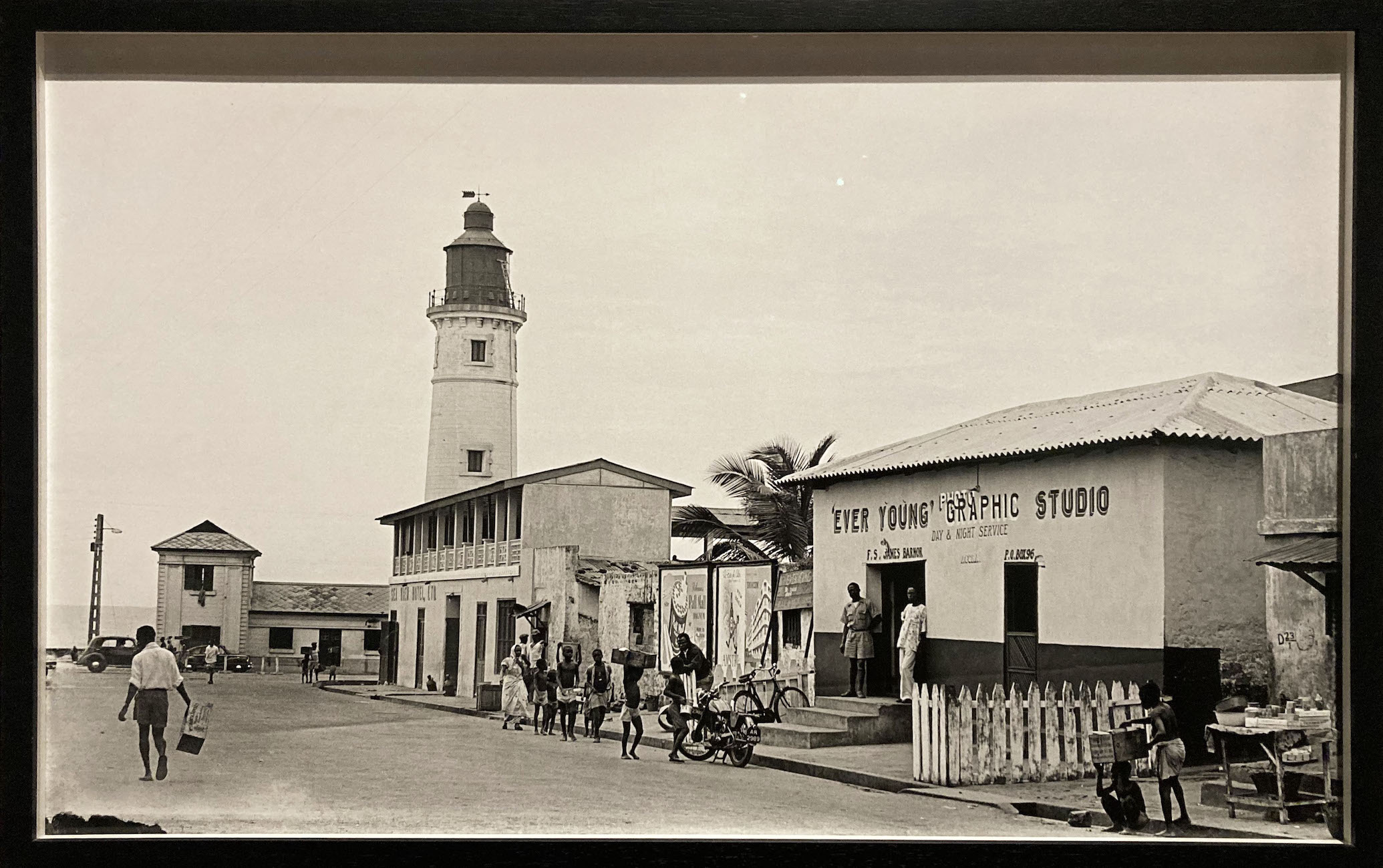

Ever Young Studio, Jamestown, Accra. 1953 (printed 2010-20) Gelatin silver print. Autograph, London. All photos images: Ashley Cook

On May 28, The Detroit Institute of Arts celebrated the opening of Accra/London, a comprehensive retrospective of photographs by African photojournalist James Barnor. This exhibition illustrates his dynamic career as a photographer whose work documented the everyday life of Africans in Ghana and the diaspora as well as major turning points in the socio-political landscapes of Accra and London between 1950-1980. Born in 1929, Barnor was a first-hand witness to life under British rule on the Gold Coast. The influence of this experience on his view of the world undeniably guided his choice of subject and composition, and his perspective as a person of African descent led to particularly careful considerations of lighting, framing, and the use of tone and color. As the largest exhibition of his work to date, with over 170 photographs spanning three decades, visitors can now learn not only about James Barnor as an artist, but about the history and evolution of photojournalism as well as the impact that the medium of photography has had on social and political change on race relations between Africa and Great Britain.

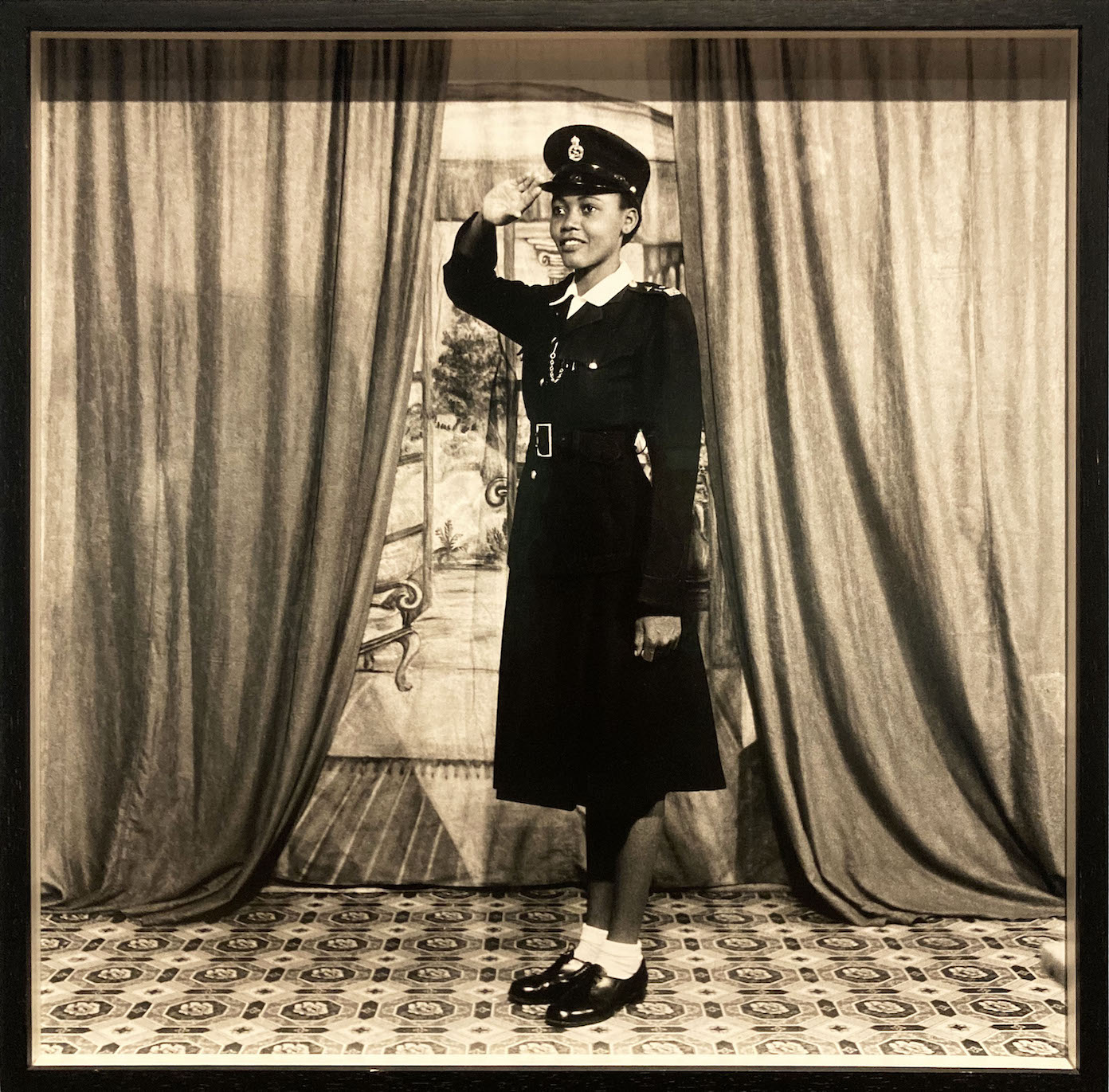

Selina Opong, Policewoman No. 10, Ever Young Studio, Jamestown, Accra. 1954 (printed 2010-20) Gelatin silver print. Autograph, London.

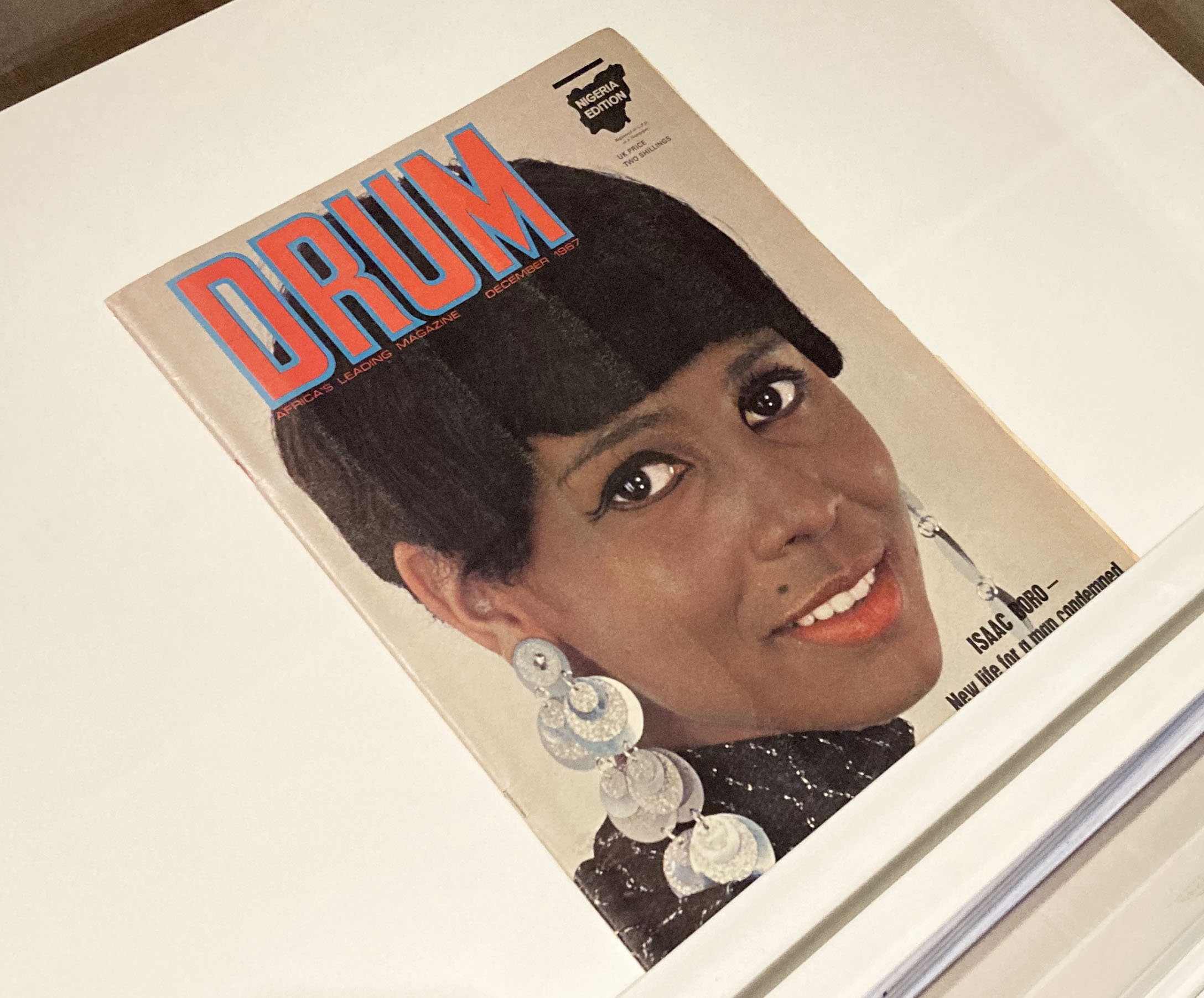

The short film presented at the exhibition’s entrance introduces us to the artist as a 91-year-old man keenly recalling details of his life and career. He recounts his youthful experience learning how to use a camera to photograph his friends, family, politicians, and professional athletes. He reflects on his role in documenting the history of Ghana from colonial to post-colonial life, his involvement with DRUM Magazine, and the expansion of his practice from Accra to London. Barnor’s light-hearted disposition in the film helps us understand how he could easily access people of various backgrounds, a trait that has proven to be critical to his professional success over time. Joy is the most consistent emotion detected in his photographs, despite their being taken in a world troubled with political unrest and racial discrimination.

DRUM Magazine, Nigerian Edition, December 1967.

The story told through this retrospective begins with Barnor’s entrance into the professional world of photography. He started to work with the Daily Graphic newspaper in 1950 and established the Ever Young Graphic Studio in 1953 as an open-air studio on the streets of Accra. Eventually, Ever Young moved to a permanent location, and Barnor used his autonomy as the business owner to explore and develop his approach to taking portraits. He depicted African life on the coast of the Atlantic and its backdrop of colonial oversight. Indigenous fishing boats share a frame with James Fort, Barnor’s friends drive a car with an iconic lighthouse in the background; elsewhere, men and women are photographed in the studio dressed in their professional uniforms. His portraits of men, women, youth and children portray the successes of local people who he recounted in interviews as having been motivated by the excitement for liberation that was on their minds and in their hearts at that time.

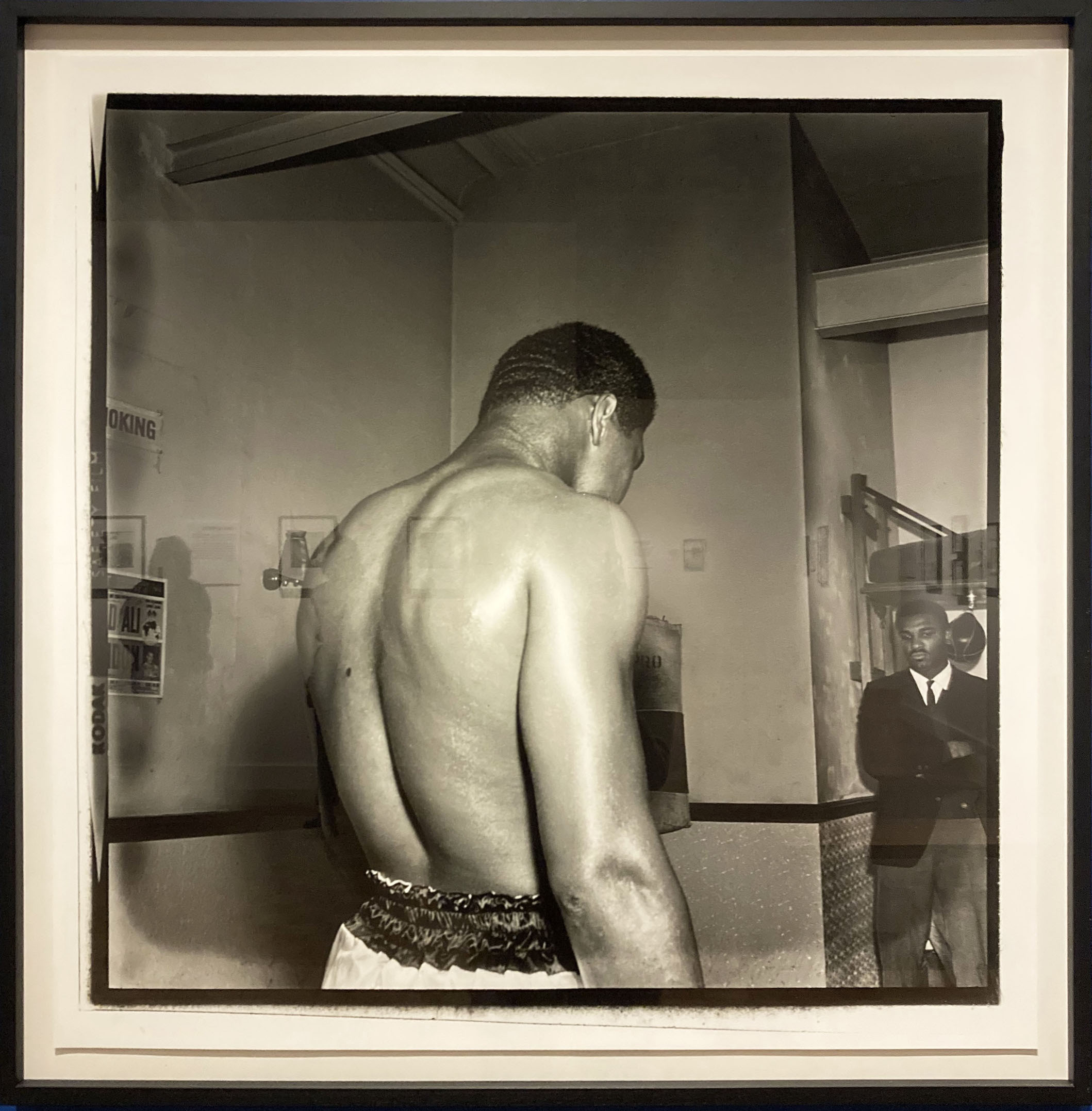

Muhammad Ali preparing for his fight against Brian London, 1966 (printed 2010-20) Gelatin silver print. Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière , Paris.

Enlarged wall images, detailed placards, vintage cameras and copies of magazines are on view throughout the space to further support the storytelling efforts of the curators. Accra/London initially debuted at the Serpentine Gallery, London in 2021. Organized by Chief Curator Lizzie Carey-Thomas in collaboration with Awa Konaté, the Assistant Curator of the Culture Art Society, Clémentine de la Féronnière, Sophie Culière of the James Barnor Archives and Isabella Senuita. The exhibition was presented at MASI in Lugano, Switzerland in 2022 before coming to Detroit. The Detroit Institute of Arts recently acquired 22 of Barnor’s photographs (now included in the Detroit-based installation of Accra/London) in an effort to diversify the museum’s world-renowned collection and to enhance its holdings of works by living African artists. Nii Quarcoopome, the DIA’s Curator of African Art, and Nancy Barr, the James Pearson Duffy Curator of Photography, worked together to bring this exhibition to a Midwest audience as part of the Detroit Institute of Art’s ongoing effort to promote its representation of people of color.

Ring Road, Accra, 1974 (printed 2010-20) Chromogenic print. Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, Paris.

Despite the collection on view being only a small sampling of Barnor’s entire archive of more than 32,000 images spanning six decades, it acts as a marker of the global growth in representation between 1950-1980 of people of color. In Accra, the photographer witnessed Ghanian boxer Ginger Nyarku publicly defeat his British opponent which challenged contemporary ideas of European superiority. He witnessed nurses, accountants, teachers and lawyers on the Gold Coast working together to weaken Britain’s control from within their government positions. He witnessed the transition of power from Queen Elizabeth II of Great Britain to Kwame Nkruma of Ghana. He witnessed a growing presence of African models on the covers of magazines in London and Barnor participated in all of this by presenting opportunities for them to be seen. His sitters were these mothers with their children, these models, these athletes, these politicians. They were carefully photographed with lighting that complimented their skin tone, and angles that framed their traditional hairstyles. They were positioned in ways that displayed the traditional patterns on their clothing. They were all shown to be confident and proud.

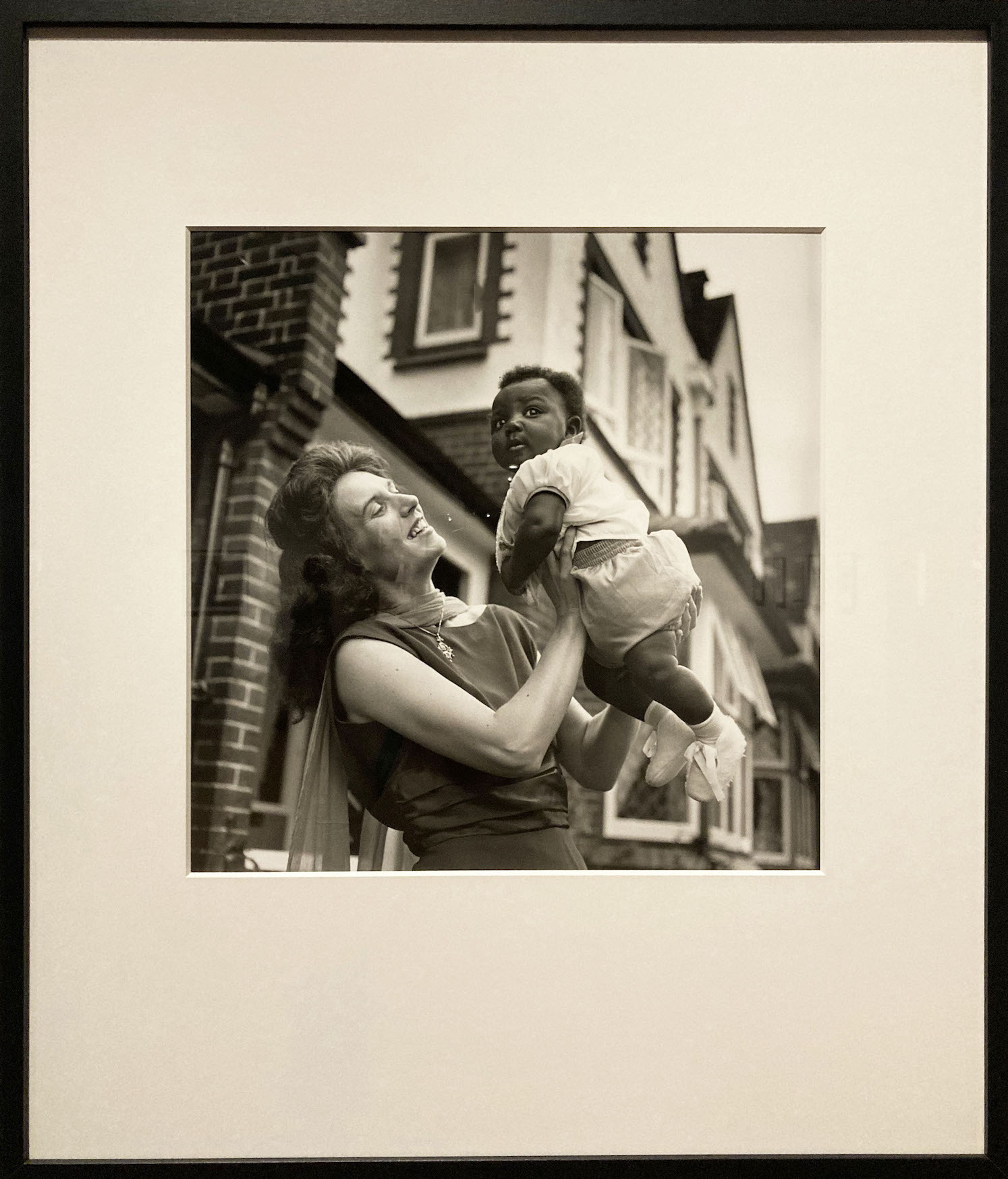

A woman holding a baby after the wedding of Mr. and Mrs. Sackey, Balham, London, about 1966 (printed 2010-20) Gelatin Silver print. Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, Paris.

Although Barnor found racism embedded throughout the United Kingdom and its colonies from the time he arrived in London until he left, the discriminatory laws and customs were not strong enough to prevent a growing appreciation for Black culture. People of both African and European descent crossed strict boundaries and protested discrimination by actively celebrating the intermingling of cultures and the exchange of knowledge it allowed. Because of this, white subjects became increasingly prevalent in Barnor’s work. Joyful dissent was recorded in everyday-life moments of interracial couples and multi-racial friend groups while a growing number of Black figures began to appear in roles they previously were not allowed to have and in places that they were previously not permitted to be.

Installation, James Barnor: Accra/London – A Retrospective at The Detroit Institute of Arts. Image courtesy of DAR

James Barnor: Accra/London – A Retrospective is on view at The Detroit Institute of Arts until Closing October 15, 2023