An installation shot of Nightshade: The World in the Evening, at Oakland University Art Gallery through March 30, 2025. All photos courtesy of OUAG except where noted.

Nightshade: The World in the Evening at the Oakland University Art Gallery explores the shadowed world as light declines to dark. It’s a liminal space – not quite here, not quite there — that ushers us into the absorbing night and the “emergence of otherworldliness,” as the introductory panel tells us on entering the gallery. This group show of 18 international contemporary painters will be up through March 30.

Gallery director Dick Goody says he wanted to touch on the ways in which twilight and darkness are spiritually and emotionally different from daylight. “If you’re working during the day, at 11 a.m., you’re not going to start thinking about metaphysics and existence,” he says. “You do that at night. So I introduced nighttime to the gallery as a way to reflect and connect to yourself.”

Sean Landers, Wildfire (Mendocino National Forest), Oil on linen, 2022.

One of the delights of Nightshade is the broad range of painters and painting styles Goody has assembled, ranging from highly realistic to the marvelously simplified or distorted. Probably the most realistic canvas, and certainly the most depressing, is New Yorker Sean Landers’ Wildfire (Mendocino National Forest), a panorama of incineration roaring on both sides of a highway, a thoroughly freaked deer frozen in the middle of the road. Indeed, both Wildfire and the next work below, Willy Lott’s House by Ulf Puder, seem to gesture towards a darker, more metaphorical twilight than just the routine passage from day to night

Landers’ canvas packs special punch right now, just after the Los Angeles fires were mostly contained. But the painting touches on the gloomy, more-disturbing twilight we’re entering, whether we know it or not – the dimming of the mostly generous world humanity has known, give or take, for 10,000-plus years, and its possible replacement by the far more hostile realm of fire and flood.

Ulf Puder, Willy Lott’s House, Oil on canvas, 2022.

Hewing more closely to the show’s focus on the literal shift from day to night is German artist Ulf Puder’s Willy Lott’s House, a much simplified and abstracted portrait of a house with a wrap-around porch under glowering gray twilight. The sky and trees feel vaguely menacing, as does the rowboat and apparent debris pushed up right against the porch. Horizontal reflections running up to the house all around suggest flooding. Somewhat at odds with this downbeat possibility, however, are large blocks of color on the wall running along the porch, which form a small, sublime composition in themselves. Goody calls Puder “a painter’s painter — he really reduces things to simple brush strokes,” resulting in works that Goody characterizes as “austerely elegant.”

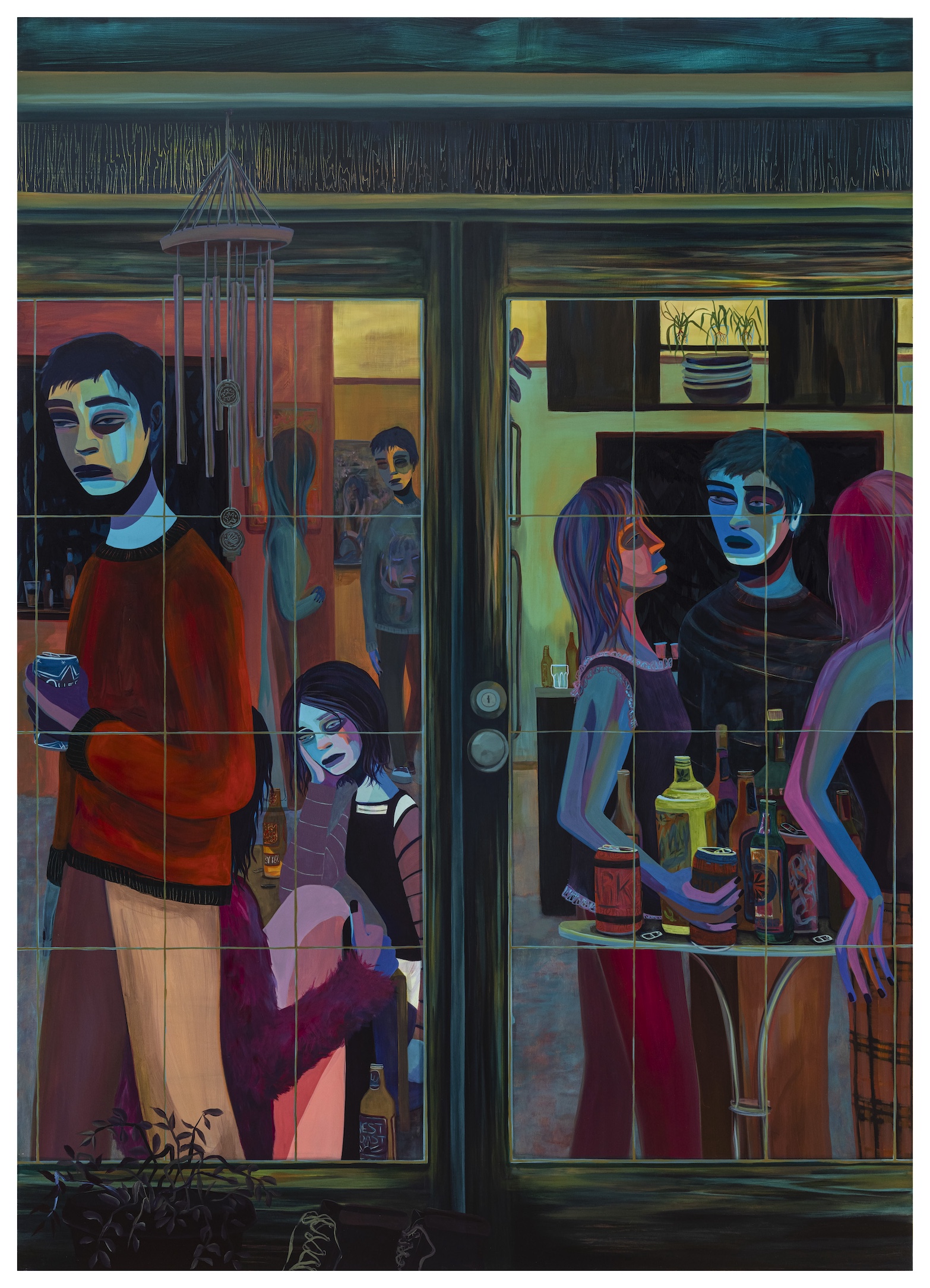

Danielle Roberts, Tomb of a Time, Acrylic on canvas, 2024

The previous two works are each essentially landscapes. For something completely different, spend a few minutes in front of New York artist Danielle Roberts’ Tomb of a Time, a glimpse through large windows of a party of young people. Goody notes the voyeuristic quality of the composition – we’re peering in at the party-goers, all of whom are blissfully unaware, cans of beer in hand, that they’re being studied. Adds Goody, “and nobody’s meeting our gaze.” Color-wise, this canvas is almost German Expressionist in its lavish use of aqua and purple-pink on faces and bare arms. The last thing to say about this gathering is that nobody appears to be having a good time. There’s a somber, hip pall hanging over everything that runs against the very notion of party – though, truth be told, we’ve all probably been there.

Goody is bullish on Roberts’ future: “You’re going to hear a lot more about her.

Marcus Jahmal, Illuminated, Oil on canvas, 2023.

And now for something completely absurd – take Marcus Jahmal’s Illuminated, an almost cartoon-like juxtaposition of odd elements: a woman’s leg stuck straight out, horizontal to the floor; a black cat about to hiss; a chandelier and a colorful grandfather clock. Goody suggests that the leg belongs to a Halloween witch, an interpretation that fits well with the black cat who’s arching its back menacingly.

Jahmal, who lives in Brooklyn and is entirely self-taught, also pulls off another nice color study in rectangles of black, mustard and violet that set off the composition’s four elements – leg, cat, chandelier and clock — very nicely. “It’s such a simple painting, but evocative of something a bit like Matisse, with his simplified, reductive forms,” says Goody, adding, “and a little bit of slapstick.”

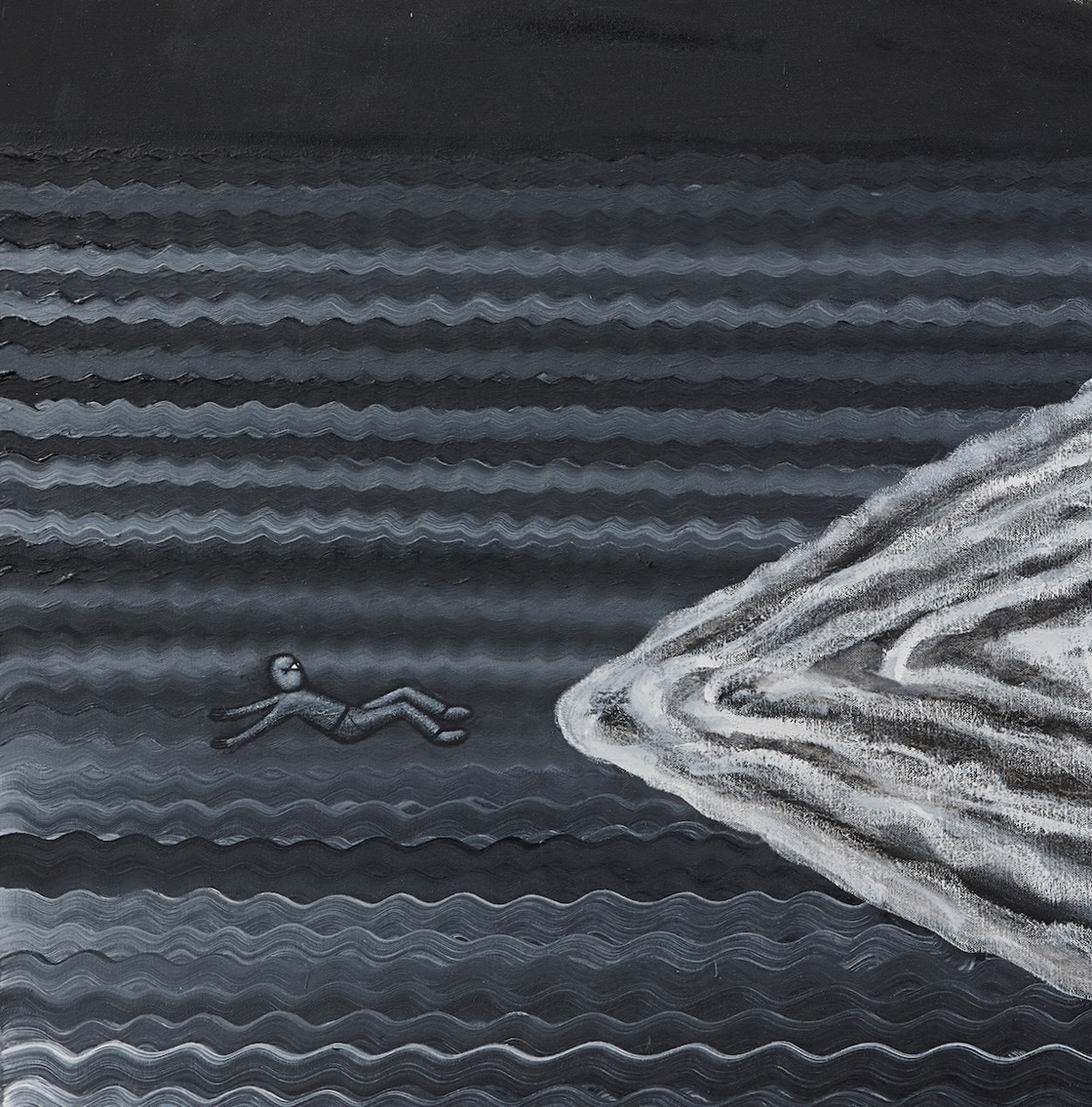

Hein Koh, The Dark Sea (detail), Oil on canvas, 2024. Photo by Detroit Art Review.

Hein Koh, also Brooklyn-based, gives us the only black-and-white work in Nightshade, as well as the most abstract and geometric. The Dark Sea stars a small, prone figure confronted by the rushing sea. “Koh’s work,” says Goody, “is usually one person or character facing some sort of ordeal,” which would fit this. Constructed in parallel or concentric wavy brush strokes a bit like dark-grey icing, The Dark Sea is a pleasurably mesmerizing visual experience. There’s a rhythm to Koh’s lines. The canvas almost seems to vibrate.

One of the smaller paintings, The Dark Sea is the last in the exhibition, at least if you walk the gallery in the most-obvious way. “It’s not very big, and I think it’s a nice coda for the show,” Goody says, and in that he’s correct. The work is surprising and engaging, and an astringent contrast to all the color that preceded it.

Anna Kenneally, Nocturnal 1, Oil on canvas, 2022.