Five painters take on reality in Group Exhibition

Trevor Young, “Beach Town” 2013, Jamie Adams, “Bride Falls, Pink Pants, Soggy Socks” 2016

“Realism gets a bad rap,” says Christine Schefman, Director of Contemporary Art for David Klein Gallery, and helmswoman of the new downtown Detroit location. The latest show to open at David Klein is Pictures of You, which features five painters, each of whom employs realism in some capacity in his renderings—and each of whom makes a pretty good case for its enduring relevance in a time where painting is no longer the leading technology for capturing reality.

Stephen Magsig, “National Theater” – 2014

The show is divided between a focus on human versus architectural subjects—and within each subject type, further divided between attempts at photo-realism versus the taking of impressionistic liberties. Within the architectural realm, artist Stephen Magsig holds down the stricter side of realism, with austere landscapes that seem, for all their industrial details, to be fundamentally about capturing light where it strikes and fades from surfaces. The works on display are larger than his exceedingly charming ongoing series, “Postcards from Detroit,” which capture this same basic subject matter at a handheld scale. While the postcard series is a bit looser, Magsig’s larger works are precise and focused—perfectly capturing, but perhaps more potentially outstanding when viewed outside the context of, the city from which he draws so much inspiration.

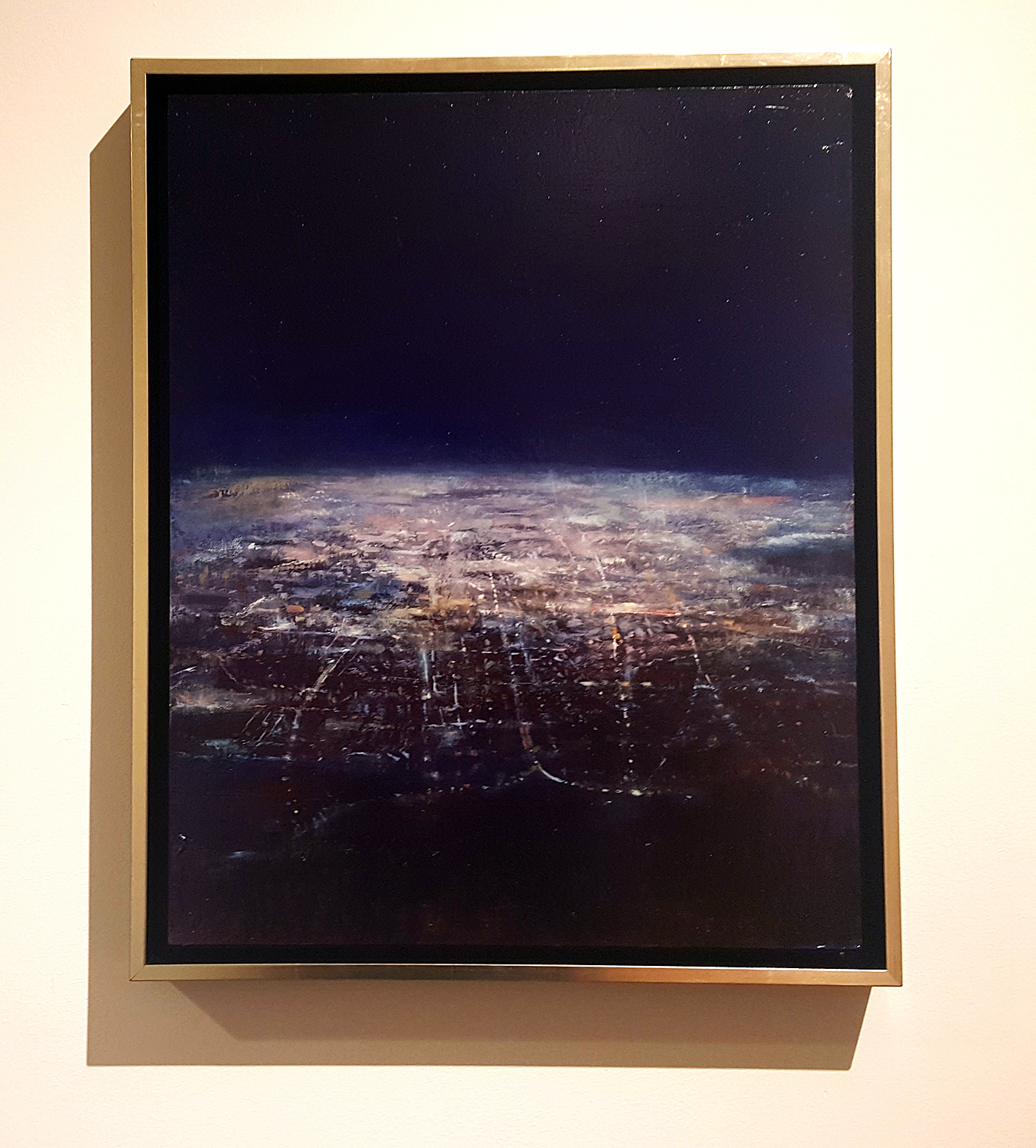

Trevor Young, “Ellipse” 20 X 16, 2016

Occupying the more impressionistic end of the architectural spectrum is Trevor Young, whose works on display include fuzzy nightscapes that evoke the dark, patchwork quilt-like city lighting grid from a bird’s-eye perspective, and nighttime tableaus of empty gas stations, their diffuse fluorescent lighting creating washes of quiet menace. These images, though outwardly stolid, nonetheless contain a kind of radiant energy; one can practically hear the buzz of lighting, the sharp intake of breath before some kind of hell breaks loose.

Robert Schefman, “Wonderland” 84 X 72 – 2016

Fighting on the side of humanity, Robert Schefman’s works seem to hew more closely to photo-realism, with a painter’s natural fetishism around capturing light sources and shadow, and perhaps a more personal kind of fetishism at play in a set of works dealing with characters and scenarios lifted from the “Clue” board game. Mrs. Green, kissed by afternoon light, gazes pensively out a window; Mr. Green is crumpled mostly out of the frame at her feet, amid a tangle of rope (he appears in a separate canvas). The eye-grabbing large-scale work that hangs at main gallery center depicts two young women in the process of sorting through boxes of records at what seems to be a twilight listening party in a driveway. Though his narratives are somewhat dreamy or disturbing, the details are sharp; by contrast, the large-scale oils on linen by Jamie Adams seem torn from vivid fantasy. Evoking classic mythical painting, but with updated clothing, and luridly modern colors, Adams’ subjects stand apart from a readily identifiable location in reality. They seem like Greek gods, engaged in floating orgies, adrift in carnal encounters, highly figurative, but like nothing of this world.

Andrew Krieger, “Campground Daredevil” – 2015

Bridging all of these works are the poignant and beautiful contributions by Detroit painter Andrew Krieger . Though clearly figurative, Krieger’s works evoke a kind of non-idealized nostalgia—more Richard Linklater than Norman Rockwell. The movement and depth created in his images—which feel unmistakably specific, seemingly torn from the raw source of memory—is enhanced by his architectural canvases. Unable to be confined to a flat picture plane, Krieger’s images literally buck, curve, and protrude into three-dimensional space. Subjects are often floating—boys jumping their bikes, a girl tumbling midair on a trampoline, a child tossed by his father poised at the apex of a cannonball into a swimming pool—their shadows casting into backgrounds that contain a wealth of funny and specific details (one bike jump is being executed, we realize, off a piece of plywood being supported from underneath by another child). Krieger is masterful with his perspectives and angles, and renders his memories in palettes that move them backwards in time. Tones are generally muted, only to be punctuated by bright blues—the sparkle on electric blue swimming pool, hot blue summer sky, vivid blue jeans on a neighborhood kid in the background.

If realism is the mode at hand, one has to wonder, what reality is being revealed? Though the show is titled Pictures of You, it seems clear that what emerges, more than an objective version of reality, is a detailed and highly subjective portrait of the mind of each of these painters. On display are the pictures indexed within the consciousness of their makers; in the end, it makes a picture of them. Which, if any, of these approaches speaks to you probably says a great deal about the snapshots you carry in your own mental wallet.