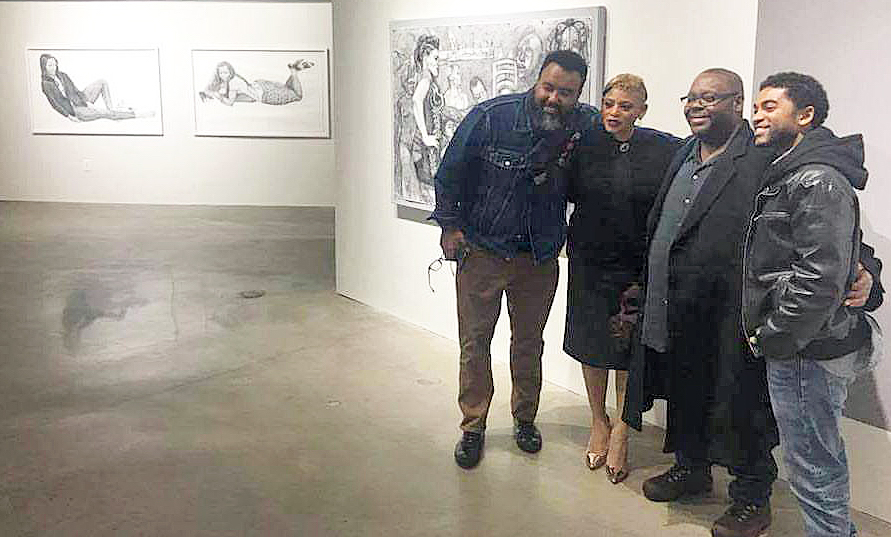

Installation image & Four Artists: Rashaun Rucker, Sabrina Nelson, Richard Lewis, Mario Moore, 2017

The hardest part about drawing connections between the pieces in Evidence of Things Not Seen—a four-person show featuring works on paper by Richard Lewis, Mario Moore, Sabrina Nelson, and Rashaun Rucker, on display at CCS Center Galleries—is not the lack of bridges between the work, but the abundance thereof.

In simplest and most general terms, this is a drawing show, so all the large, stand alone works, as well nearly two dozen small works in Nelson’s Baldwinning series, are aesthetically unified as hand-drawn, mostly in graphite and charcoal. These are also all artist of color, dealing with issues of Black representation, and presenting Black subjects. Despite each artist having radically different interests, influences, and approaches to the way they look at their subjects, the gallery is utterly harmonious and unified in its aesthetics. Black on black, in shades of grey.

Installation image, CCS Center Galleries, 2017

Then, too, there are an abundance of interpersonal connections underpinning this group of artists. Lewis and Nelson were studio mates during their undergraduate years at College for Creative Studies (where Nelson now teaches), and she and another close fellow, poet Jessica Care Moore, appear as characters in Lewis’s works. Nelson is also mother to Mario Moore, who looked up to Lewis, by way of his connection to Nelson, and followed his exact educational path, starting from Cass Technical High School, through undergraduate studies at CCS, and on to pursue an MFA at Yale. Just as Lewis and Nelson hang together in one generation, Moore and Rucker represent the next (literally, in fact, because Nelson is Moore’s mother), and it is fascinating to see the generational divisions and similarities between the two cohorts.

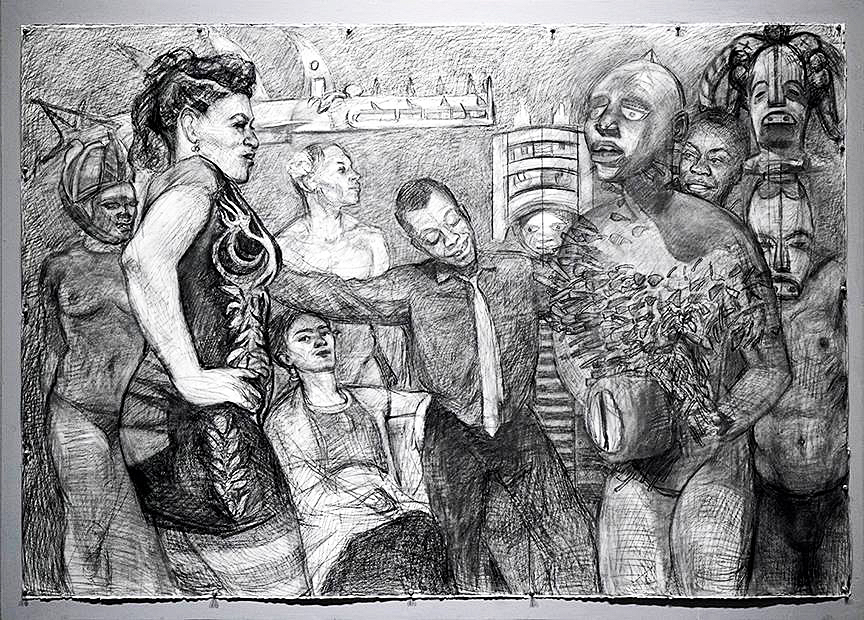

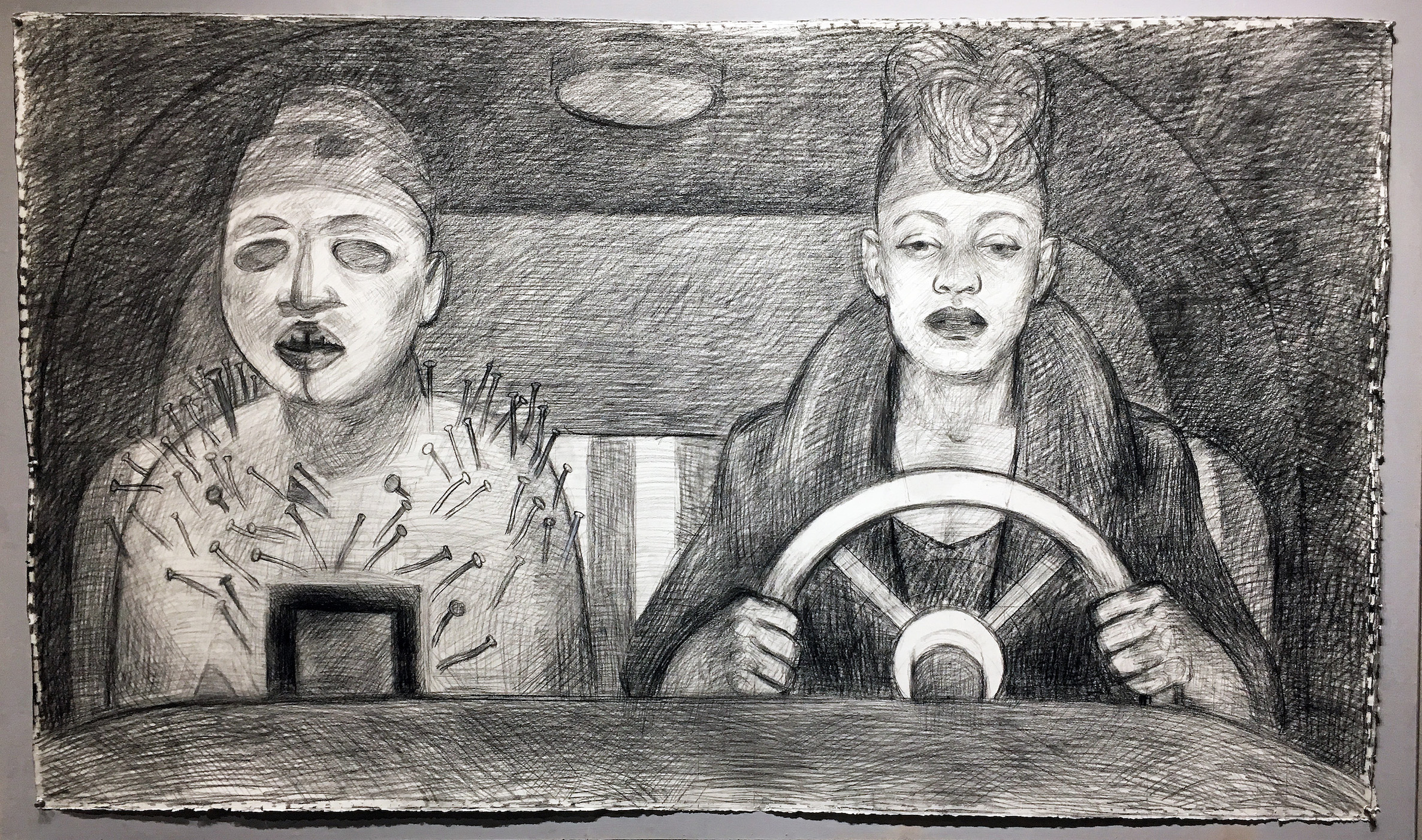

Richard Lewis, Rent Party, 48 x 60″ Charcoal, Pencil 2016

For example, one might highlight the magical realism present in the works of Lewis and Rucker, who both favor the fantastic and the uncanny, rather than the more directly representational portraiture of Nelson and Moore. Rucker presents a body of work around a single theme: the visual merging of portraits of young black men with the bodies of pigeons. With mug shots as his source material, Rucker is seeking to emphasize the correlation often made between young, urban, black male populations, and undesirable vermin, such as pigeons. Faces morph into beaks, a head springs from the body of a pigeon, or wings and beaked head emerge from the twisted legs of a fallen human body. Likewise, Lewis’s subjects occupy a time-compressed and surrealistic world, where Sabrina attends a rent party with James Baldwin and Frida Kahlo, or drives home at night with an nkisi figure in the passenger seat. These nkisi are a traditional African spiritual sculpture form, often covered with individually driven nails, and seen as protector spirits, both in terms of their cultural origins, and in terms of Lewis’s repurposing of them as subjects.

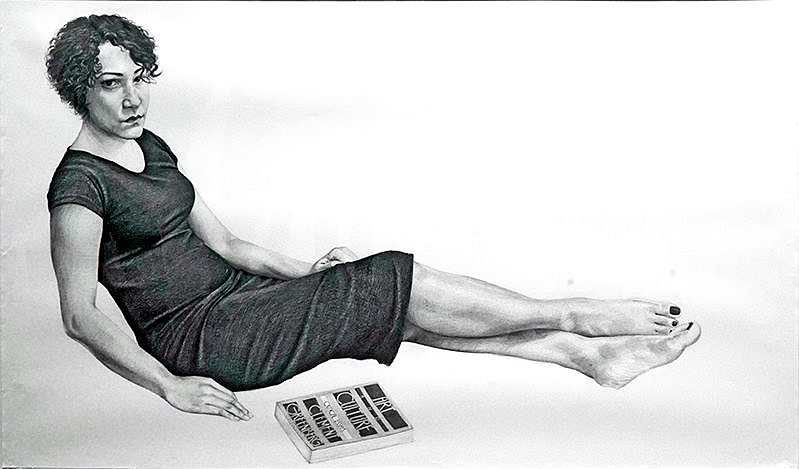

Mario Moore, Lucia, 2015, Graphite on Paper

Or perhaps one could draw another parallel between Nelson and Lewis’s tendency to make cultural references, while Moore and Rucker are making portraits from everyday figures. In addition to using his studio-mate as muse, Lewis’s tableaux are recast and reconstructed scenes from film noir features, such as Shipwrecked and Saints and Sinners. Nelson, of course, takes James Baldwin as her muse, and the corner of the gallery devoted to her work is papered with nearly two dozen examples of individual portraits she has drawn of the writer, in addition to filling four complete sketchbooks with nothing but drawn and stitched James Baldwin portraits.

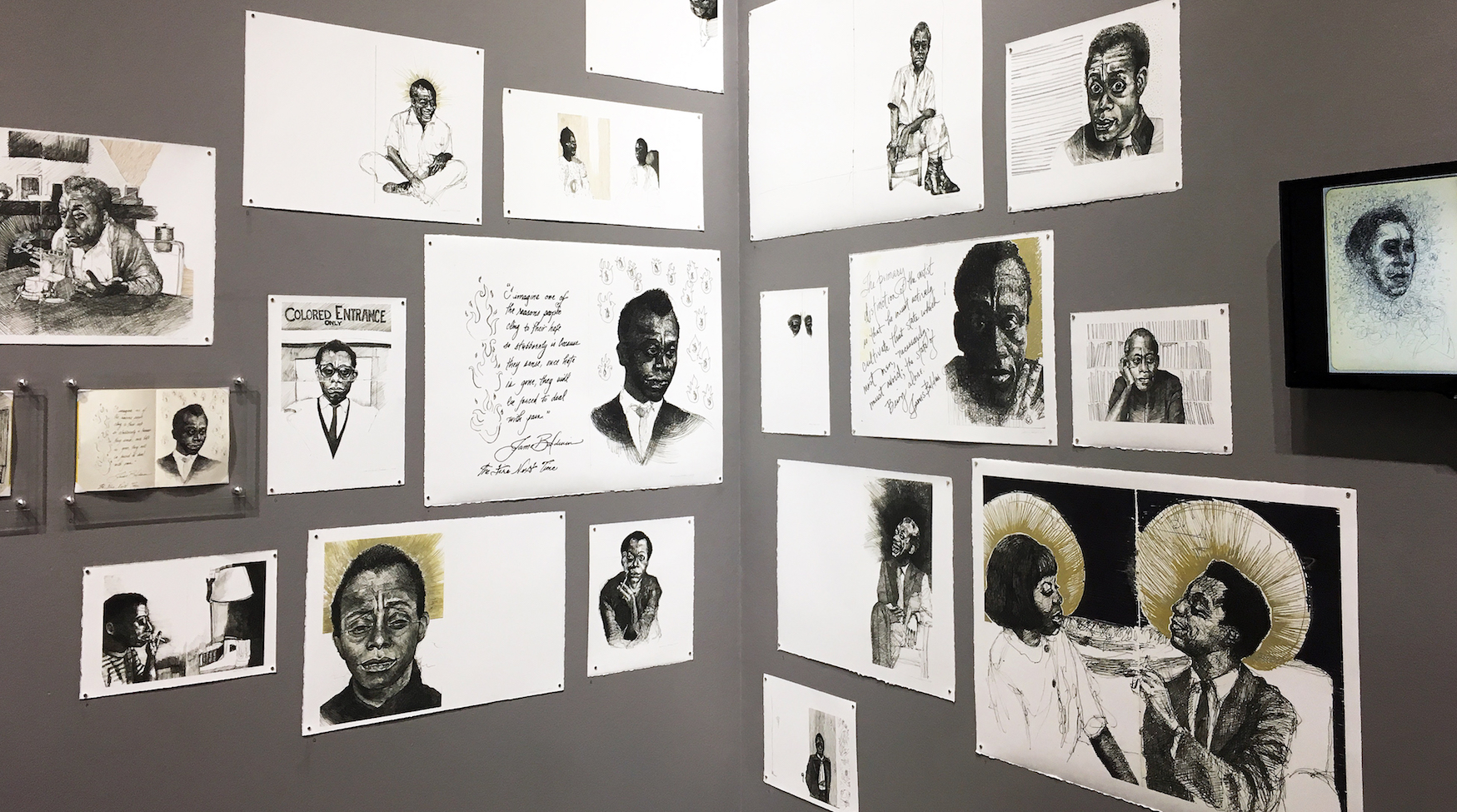

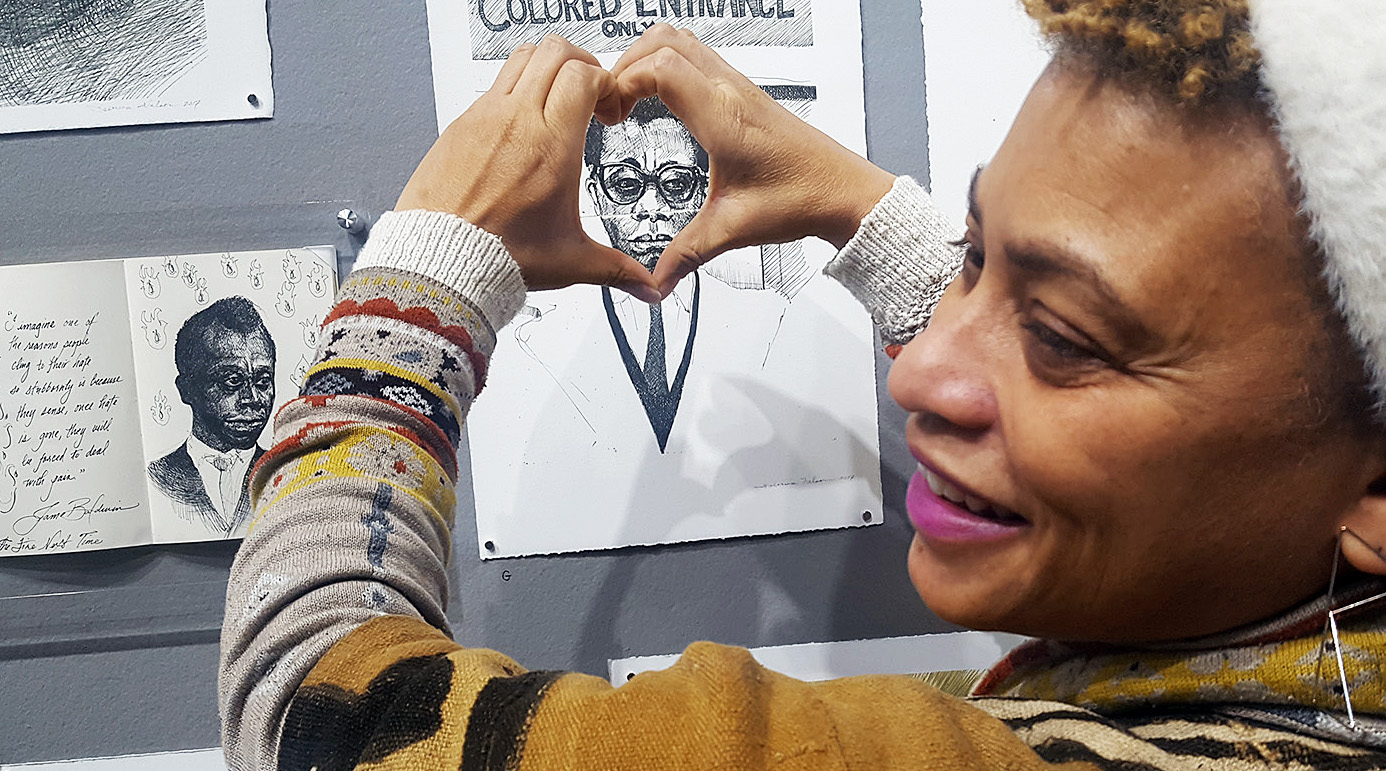

Sabrina Nelson, Baldwinning, 2016-17, Sketchbook drawings, Glclee prints, micon ink, gold ink, silver ink, thread, and video

“One of the reasons I started drawing James Baldwin is because Jessica Care Moore invited me to the James Baldwin conference in Paris,” said Nelson, during a tour of the gallery. “She was doing a plenary there with three other artists, called “What Would James Baldwin Do?” It was about him being an artist, and as an artist, what is your responsibility in the world? What do you say, and what is your weaponry? For her it is her poems, and for me it is my hands and my drawing and my painting.”

Sabrina Nelson poses with her many images of James Baldwin.

One sees the love of reading and writers transferred from mother to son, as all of Moore’s hyper-realistic, large-scale portraits feature women in his life, taking a break from reading to look at the viewer. Despite Moore’s extremely straightforward and beautiful renderings of women—many of whom were classmates at Yale, as well as his girlfriend—contain their own sly cultural references, in the telling detail of the book they are reading. But more arresting in these works is the ease and comfort with which these women seem to meet the gaze of the artist and the viewer on entirely their own terms. Unlike Rucker’s pigeon-hybrids, who seem to search the viewer for evidence that they can be seen at all, Moore’s women let you know that they are not to be objectified.

Richard Lewis, They Drive by Night, 26 x 40″ Conte crayon on Rives BFK

One could weave connections through these powerful works for days—the energy fairly radiates between them—but there’s only just time to catch this show before it closes, so I’ll end with an admonition to take some time with it before the December 16th closing. One can hardly build a case for the connections within Evidence of Things Not Seen, after all, if you don’t go see it for yourself.

Evidence of Things Not Seen continues at CCS Center Galleries through December 16.