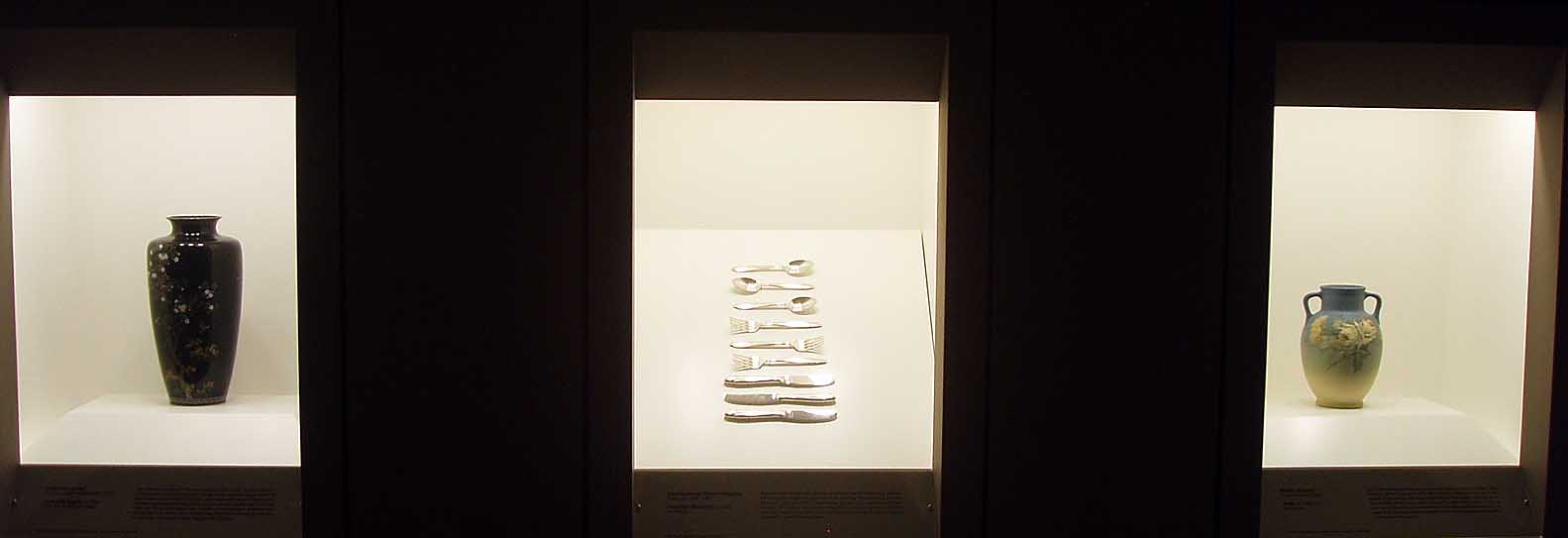

Installation image, Two bowls, and silver setting

“Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful,” urged the great designer and social reformer William Morris to an audience in 1880. Hardly just making a quip about interior design, Morris was being a counter-cultural thorn in the side of the Victorian capitalist and industrial establishment, whose factories churned out mass-produced artless products, and whose workers were accorded little more status than that of the machine. Morris argued that there was a better way, and even established a workshop that taught people skilled trades in the applied arts, in which workers could harness their creative agencies while earning living wages and producing objects of quality and beauty. This launched the Arts and Crafts Movement, the reverberations of which were felt on both sides of the Atlantic.

Paul de Lamerie, English, 1688–1751. “George II Oval Cake Basket,” 1742. Silver. 14 7/8 x 11 7/8 x 11 7/8 inches. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. William L. Richards through the Viola E. Bray Charitable Trust, 1984.23

Not all the works that comprise the show Useful and Beautiful on view at the Flint Institute of Art are the products of the Arts and Crafts Movement (though some, like those produced by Liberty & Co. or the architectural studio of Frank Lloyd Wright, absolutely were), but they all stand in the tradition of skilled artisan craft that seamlessly integrated functionality with exquisite design. Collectively, this diverse ensemble of work voice a triumphant rebuttal to Oscar Wilde’s quip that “all art is quite useless.”

The chronological and geographical scope of this smallish exhibition is impressively broad. Spanning a 500-year breadth, the show presents examples of decorative arts ranging from a lavishly decorated 17th century wheellock pistol to stained glass by Frank Lloyd Wright. A sizeable number of these works hail from non-western cultures (Asian and American Indian, specifically) which never drew a line between the fine and applied arts, as did the Western/European world. Everything on view comes from the FIA’s permanent collection, and the FIA really is the perfect venue for this exhibit: in addition to a muscular collection of traditional “fine art,” the museum now boasts a newly opened wing that displays a world-class collection of ceramic and glass art, much of which fudges the boundary between the beautiful and the functional.

Artist Unknown, German. Fullstock High Art Wheelock Pistol, ca. 1680. Wood, steel, ivory, and mother of pearl. 16 7/16 x 4 13/16 x 1 7/8 inches. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. George H. Greidinger, 1976.

These artifacts are diverse and sometimes surprising. A pair of engraved golden cigarette cases from Japan possesses the lavish attention to detail that we might expect instead from devotional artifacts belonging to a Constantinian-era emperor, or perhaps something unearthed from a Viking burial. The same could certainly be said of a Celtic-inspired bowl designed by Alfred Knox for Liberty & Co. Usually the largeness of a work of art seems to grab people’s attention, but in the case of six finely-crafted tiny salt and pepper dispensers (imagine a set of tiny witch’s cauldrons, but made of silver and about the size of a thimble, replete with a tiny serving spoons), it’s precisely the smallness of this set that makes it such a tour-de-force of applied design. A tiny pair of Sioux children’s moccasins, adorned with meticulous beadwork, is similarly arresting for their petite size. Perhaps the most unexpected objects in the show are the set of streamline 1930s-era Art-Deco silver cutlery, custom-made exclusively for American Airlines, and intended to stress the point that travelling by airplane was the fabulous and luxurious modern way to travel (contemplate this as you attempt to pry apart your next airline meal with a semi-functional plastic spork).

Liberty & Co., British, founded London, 1875. Bowl, ca. 1900. 3 1/2 x 7 1/8 x 7 1/8 inches. Gift of Janis and William Wetsman, 2016.

Many works on view, beautiful as they are, were produced by anonymous artisans who likely never imagined their craft would one day appear in an art museum—decorative Pueblo pottery, for example, or a pewter flagon from Germany. Nevertheless, this show does boast a selection of art-world heavyweights. There’s a decorative ceramic bowl created in collaboration with the famed American painter Andrew Wyeth. Viewers will also see one of the stained-glass windows designed by Frank Lloyd Wright for a home at Midway Gardens in Chicago; heavily inspired by the Arts and Crafts Movement, Wright famously custom-designed every component of a building, including light fixtures, furniture, silverware, and windows.

Artist Unknown, German. Flagon, n.d. Pewter. 12 9/16 x 4 5/16 x 6 ¼ inches. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Keith Davis, 1972.

This exhibition rhetorically asks if there really is a meaningful distinction between the fine and decorative arts, and playfully blurs the boundary between these two categories. It’s a question perhaps best posed by a bronze doorknocker crafted by Renaissance sculptor Tiziano Aspetti, which features a Greco-Roman inspired Venus standing in elegant contrapposto, directly quoting the famed Aphrodite of Knidos, one the most copied sculpture of classical antiquity. At this level, distinctions between the fine and applied arts become, in the final analysis, a bit petty.

Collectively, these works serve to break down some unnecessary distinctions we’ve created to categorize the arts, but there’s an understated social element to this exhibit as well. This show wistfully looks backward to a time before the Walmartification of culture, which invariably takes material culture down toward the absolute lowest threshold of quality and craft that people will settle for. In its quiet way, this show suggests that technological advancement is not necessarily always progress forward, and that perhaps we shouldn’t always be so quick to sacrifice beauty for the sake of efficiency.

Useful and Beautiful exhibition at the Flint Institute of Art through July 26, 2020