MSU Broad and Able Eyes

Over the past few months, cultural institutions have out of necessity navigated creative ways of making their content available online. This works better for some forms of media than others. Most of us already experience music digitally by default, and what happens in the recording studio is pretty much exactly what we experience through our headphones; little gets lost in translation. But the visual arts exist in space, and they lose a dimension when viewed online. But emerging technologies, particularly 360-degree photography and virtual reality (VR), have the potential to make digitally exploring visual culture much more rewarding.

Without getting into the technical details, a VR headset (like those offered by the brands Oculus and Vive) makes the Street View content from Google Maps fully immersive and interactive. Since Google has taken its cameras into many museums, cultural institutions, and architectural spaces, this makes it possible to navigate these spaces not just on a regular computer screen, but also in VR. With a VR headset, we see the Google Map imagery life-size and surrounding us in 360 degrees, and it really does disconcertingly seem to place us on location.

There are admittedly some problems with viewing art in virtual reality. Pixilation can be an issue. On a regular computer screen, a Google Street View image might look just fine, but with a VR headset, even slightly pixelated images are rendered as aggravatingly blurry. The Google Street View rendering of the interior of New York’s Metropolitan Art Museum, for example, looks great on a computer screen, but the paintings get pretty fuzzy when seen in VR. Exterior views of architectural spaces are much more forgiving. A second problem (with or without VR) is that Google’s 360-degree cameras photograph interiors from a vantage point of about eight feet in the air, which can be problematic; if you try to “stand” directly in front of a painting you’ll often find yourself looking down at the work from an awkward angle.

In some instances, though, this elevated vantage point is actually useful. One of the best places to digitally explore is the Doge’s Palace in Venice; the extra boost we get from Google’s camera offers us a marginally better view of the Renaissance murals which cover every inch of its walls and ceiling. We can also get satisfyingly closer to the marbles which once adorned the Parthenon, now housed in the Acropolis Museum in Athens. And we’re offered a much better perspective of some of the larger than life, cinematic Napoleonic propaganda (such as David’s Coronation of Napoleon) that adorns the walls of the Palace of Versailles.

Among the museums which are rendered in sufficiently high definition so as to not appear pixilated (even when viewed through an unforgiving VR headset) include the British Museum, where the imagery is so crisp that we can read the didactic text on the wall. The same could be said for the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Also impressively lucid are Google’s renderings of the Getty Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago.

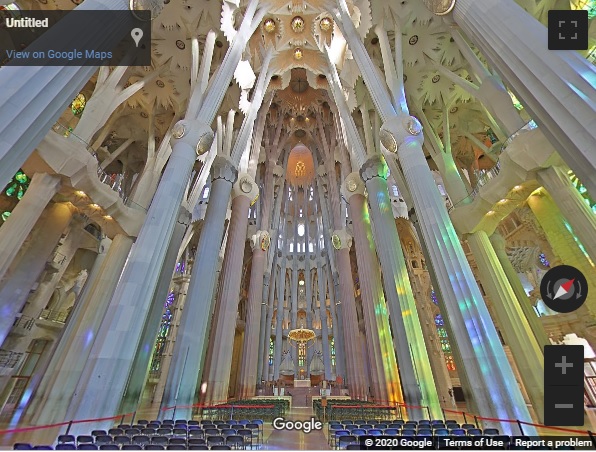

Some architectural spaces and ensembles especially worth exploring include the Peruvian city of Machu Picchu and the Palace of Versailles and its gardens. The dazzling, colonnaded interior of the Mosque of Cordoba [later converted to a cathedral] is a fascinating bit of history set in stone; as we navigate its interior, we experience it as a mash-up of both arabesque and European architectural elements. A personal favorite space to digitally wander is the luminous interior of Barcelona’s Sagrada Familia. Closer to home is the much under-rated Driehaus Museum in Chicago, a three-story Gilded-Age mansion which has been preserved and functions as an excellent period museum.

“Machu Picchu as viewed in Google Street View”

“La Sagrada Familia as viewed in Google Street View.”

In Michigan, Google’s omniscient cameras have photographed nearly all our streets, but disappointingly few cultural institutions. One notable exception is Meijer Gardens and Sculpture Park in Grand Rapids, rendered in impressively high resolution. The park is now open again, but during the Covid shutdown, Meijer Gardens found inventive ways to bring the gardens to the public via Facebook, including posting 360-degree video walk-throughs of some of its spaces; although not as immersive as VR, this nevertheless made its Online content satisfyingly interactive.

One street in Michigan that doubles as a cultural institution is the Heidelberg Project. An interesting feature about viewing Google Street View through the VR App Wander (a Google Map program specifically packaged for Oculus VR headsets) is that whenever a place has been photographed by Google more than once, we can reset the date, and see what the place looked like at each successive photoshoot. The Heidelberg Project is particularly fluid, so it’s interesting to see how the project evolved yearly (starting in 2009, when Google first photographed the space) as its elements and structures appear and disappear.

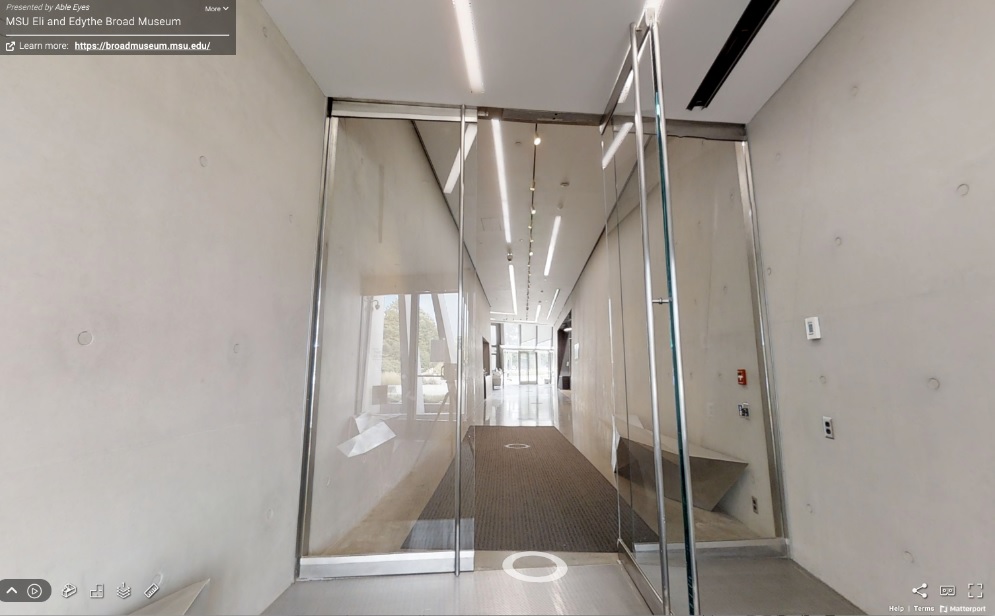

We can also virtually navigate parts of Michigan State University’s Broad Art Museum, which offers a VR-compatible virtual tour of its space, and in impressively high resolution. The interior was photographed not by Google, but by Able Eyes. Although we can’t enter any of the Broad’s exhibition galleries in this walk-through, we can still navigate the atrium and public spaces, which are enough to sufficiently showcase architect Zaha Hadid’s relish of counterintuitive, angular forms.

MSU Broad and Able Eyes

There’s certainly no substitute for seeing art and architecture in person, of course. But it’s nevertheless exciting to be on the cusp of emerging technologies which help us experience visual culture in full immersion. Increasingly, it’s becoming possible to experience art digitally much like we can with music, with little getting lost in translation. Wolfgang Goethe once even described architecture as “frozen music,” and these new technologies allow us to explore these spaces in surprisingly lucid detail, note for note, and in fully immersive, navigable three dimensions.