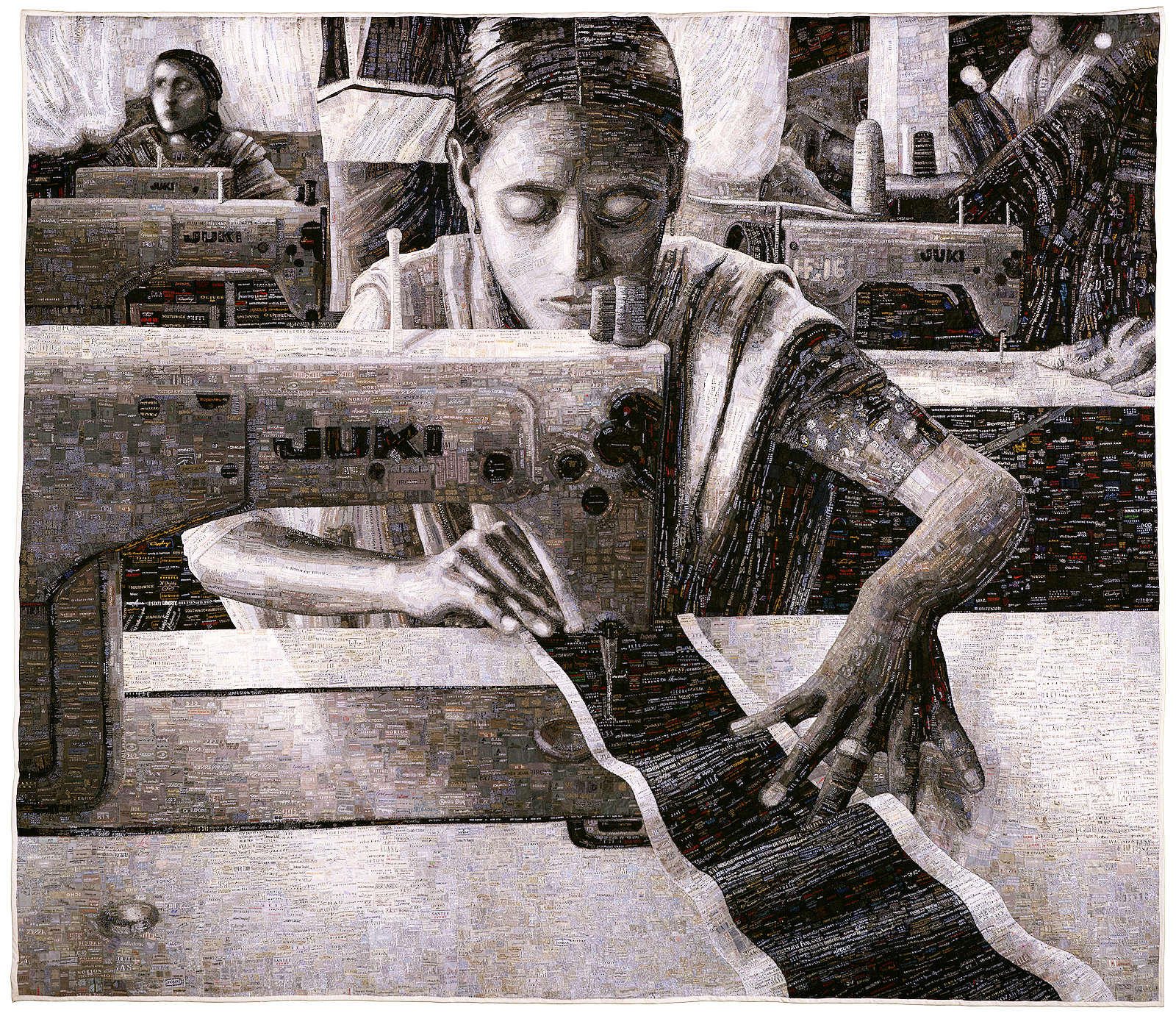

Therese Agnew, Portrait of a Textile Worker, Shorewood, WI, 2002, clothing labels, thread, fabric backing. 94 1/2 x 109 3.4 in. Image Credit: Museum of Arts and Design, New York; purchase with funds provided by private donors, 2006 Photo: Peter DiAntoni

There’s something visceral and tangible about quilting that sets it apart from other artistic media. In a very literal sense, quilters stitch together the fabrics of the past and present, imbuing each work with a historical and cultural weight. Radical Tradition, on view until February 14 at the Toledo Art Museum, explores how American quilts of the 19th through 21st centuries have engaged with prescient social issues. The show supplements works from the TMA’s own collection with a generous selection of quilts from nearly two dozen lending institutions, and together they demonstrate the medium’s historically robust social engagement, speaking to issues ranging from racial justice, prison reform, women’s suffrage, LGBTQ rights, immigration, and much more.

Radical Tradition forcefully challenges our preconceptions of what a quilt even is, and what’s on view might better be described more broadly as “fiber art.” Ben, for example, greets viewers at the show’s entrance. Ben, from the TMA’s own collection, is an endearing fiber sculpture by Faith Ringgold of a 1970s-era homeless man, brandishing buttons, pins, and patches which serve to tell his story. He’s a veteran of the Vietnam War, and the meagre few possessions he totes and the bottle of alcohol he clutches are suggestive that he’s fallen onto hard times. The buttons he wears call for various progressive political and social reforms. It’s a very human, heartfelt, and sympathetic portrait.

Faith Ringgold, Ben, 1978. Soft sculpture/mixed media, 39 x 12 x 12. Toledo Museum of Art (Toledo, Ohio) Image Credit: © 2020 Faith Ringgold / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Courtesy ACA Galleries, New York

At Work III isn’t even fiber, but rather backlit strips of 16mm polyester film sewn together to form a traditional “log cabin” quilt pattern. The film strips are extracted from various industrial films showing anonymous female hands engaged in labor in the textile industry, and the work addresses the historical anonymity of those in the textile and garment industries.

Sabrina Gschwandtner, Hands at Work III, 2017, 16mm film, polyester thread, LEDs, 26 7/8 x 27 x 3 in. Image Credit: Image Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery

While this exhibit is perhaps liberal with what materially constitutes a quilt, there’s certainly a thematic continuity in the show’s focus on quilting and social engagement. Many of the quilts on view (especially the older ones) were created to raise money for various social causes or humanitarian organizations, such as the Cradle Quilt (for the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society), Liberty Tree (for the temperance movement), and the Red Cross Quilt (to support the organization during the First World War). The Vietnam Era Signature Quilt was made to raise funds to rebuild a North Vietnamese hospital that had been bombed during the Vietnam War, and it includes the signatures of Leonard Bernstein, Gloria Steinem, and Pete Seeger, among many others.

Abolition Quilt, ca. 1850. Silk embroidered quilt, 59 x 59 in. Historic New England, 2.1923. Courtesy of Historic New England. Loan from Mrs. Benjamin F. Pitman, 2.1923.

Gen Guracar, Vietnam Era Signature Quilt, c. 1965-1973. Made in Mountain View, California, 80 x 63.5 inches. International Quilt Museum, Gift of Needle and Thread Arts Society, 2007.008.0001 Image Credit: International Quilt Museum, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

In many, the very fabric of these quilts helps to underscore their message, such as Portrait of a Textile Worker by Terese Agnew. It’s an image based on a photograph taken by an undercover human rights advocate of a sweatshop worker in Bangladesh. The quilt comprises 30,000 individual clothing labels, each only individually visible up close; mosaic-like, together they form an image of a textile worker stationed at her sewing machine. It’s a poignant image that speaks to the exploitation of underage and underpaid laborers in the garment industry who work as temporary contractors for big-box clothing brands.

One particularly arresting and prominent work is the ensemble of large, triangular quilt blocks from the International Honor Quilt, a project initiated by Judy Chicago and originally intended to complement her iconic Dinner Party. Just like each individual place setting of Dinner Party, here each triangular block pays homage to a significant woman from history or mythology, and in its entirety the work consists of 542 individual sections. Each block was created by a different individual, and they reflect a wide variety of styles and techniques.

Judy Chicago, International Honor Quilt (IHQ), initiated by Judy Chicago in 1980, Created in response to The Dinner Party. Hite Art Institute, University of Louisville. Image Credit: © 2020 Judy Chicago / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

As a telescope enthusiast, I was naturally drawn to Anna Van Mertens’ evocative Midnight until the first sighting of land, October 12, 1942, six miles off the coast of current day San Salvador Island, Bahamas. It’s a black quilt which, as the title implies, charts the course of the stars in a patch of sky as they would have been seen by Columbus and his crew during these hours, so fatefully freighted with the weight of history to come.

This is a visually satisfying show with much to offer, and it makes the most of the TMA’s spacious New Media gallery suite. There’s also an impressively broad range in style and content. Some of the works range from the playfully exuberant VanDykesTransDykesTransanTransGranmx DykesTransAmDentalDamDamn (a showstopping, mural-scale work that is as massive and wild as its title implies) to the solemn Dachau 1945, a quilt made from the subdued, neutral patches from prison uniforms of inmates of Germany’s notorious Dachau concentration camp. Radical Tradition masterfully combines beauty, poignancy, energy, and conceptual depth, and it’s a show that triumphantly lives up to its wittily oxymoronic name.

Unknown Maker, Dachau 1945, 1945, Wool, 69 1/2 x 77 in., Michigan State University Museum Collection, 2015:66.2. Image Credit: Courtesy of Michigan State University Museum. Photographed by Pearl Yee Wong

Radical Tradition is on view at the Toledo Museum of Art through February 14. The show is accompanied with an exhibition catalogue.