Mary Fortuna and Adrian Hatfield @ Oakland University Art Gallery January 19-March 24, 2024

Nostalgia and Outrage, Installation, Oakland University Art Gallery. All photos by K.A. Letts.

Nostalgia and Outrage, an exhibition of artworks by fiber artist Mary Fortuna and multi-media collagist Adrian Hatfield, opened on January 19 at Oakland University Art Gallery in spite of Michigan’s typically lousy winter weather. The paintings, textiles, toys, mobiles and dioramas on display address death, mass extinction, disaster (both personal and societal) and general apocalypse–doomsday themes that might seem gratuitously gloomy for this dark time of year. But instead, this lively–even cheerful—exhibition reminded me of the well-known aphorism: “The situation is hopeless but not serious.”

Mary Fortuna, Protection Flag, 2023, linen, cotton applique, embroidery.

Fortuna and Hatfield approach their art in ways that simultaneously diverge from and resonate with each other. In the slim but informative catalog that accompanies the show, gallery director Dick Goody teases out insights from the artists on their motives and methods. “We both have a sense of humor and we’re both anxious or pissed off about the state of the world. We share environmental concerns,” says Fortuna. Hatfield adds that the two also use storytelling or narrative as a hook and often reference archetypal characters in their work. In the interview, Hatfield and Fortuna trace recurring themes in their art to childhood experiences. Echoes of each artist’s early obsessions linger in their current art practice and lend an air of playfulness to many of the artworks.

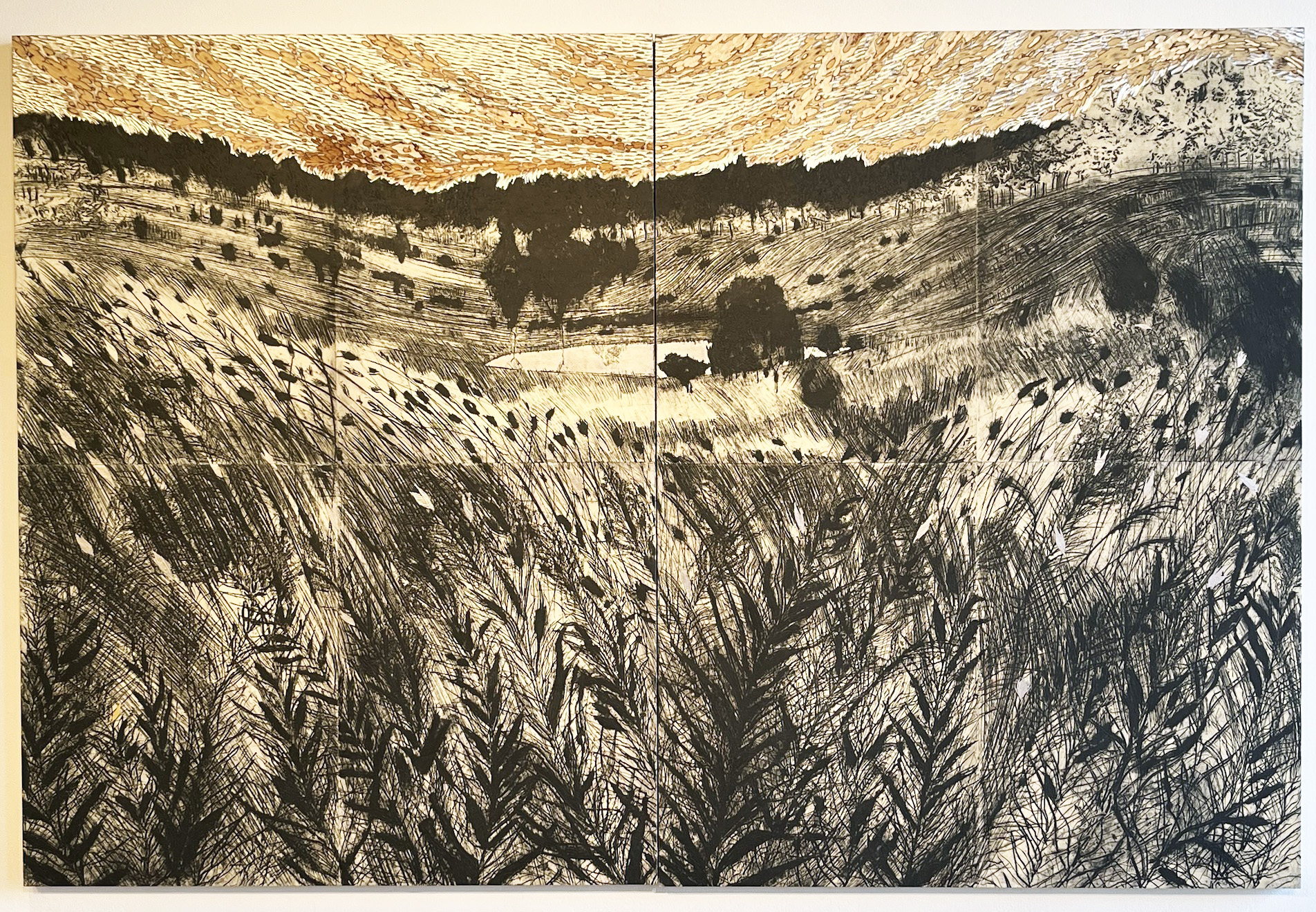

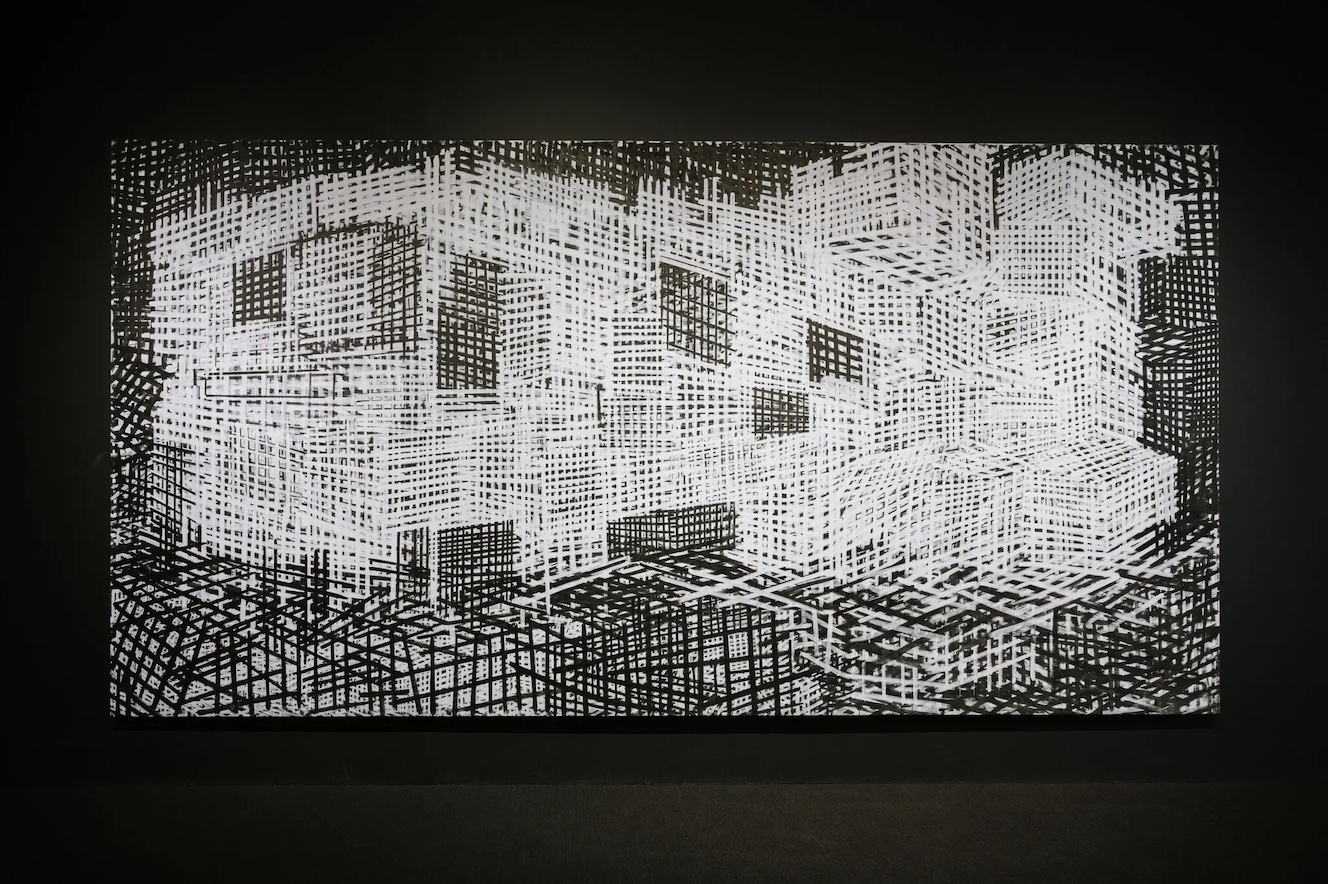

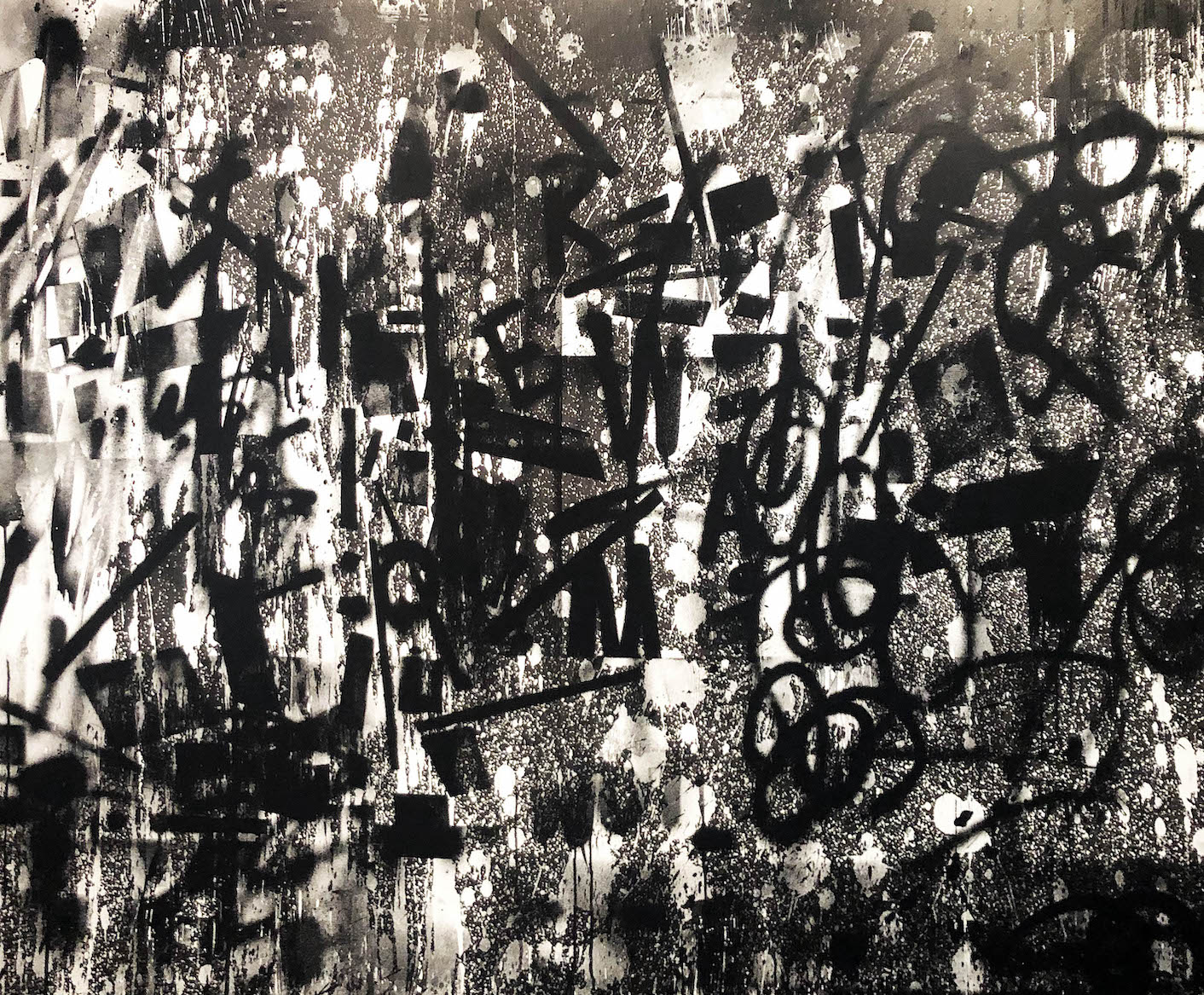

Adrian Hatfield, Teamwork makes the dream work, 2022, oil and acrylic on canvas.

Mary Fortuna

Fortuna remembers that as a child she expected to become “a nun, a cook or a nurse.” She grew up mostly in the company of her older sister Mady and describes this pivotal relationship as one based on creativity and invention. “We spent hours together drawing, making up stories, sharing books, dressing up, making dolls and puppets and paper dolls and comic books. We wrote little plays and made up songs,” she says.

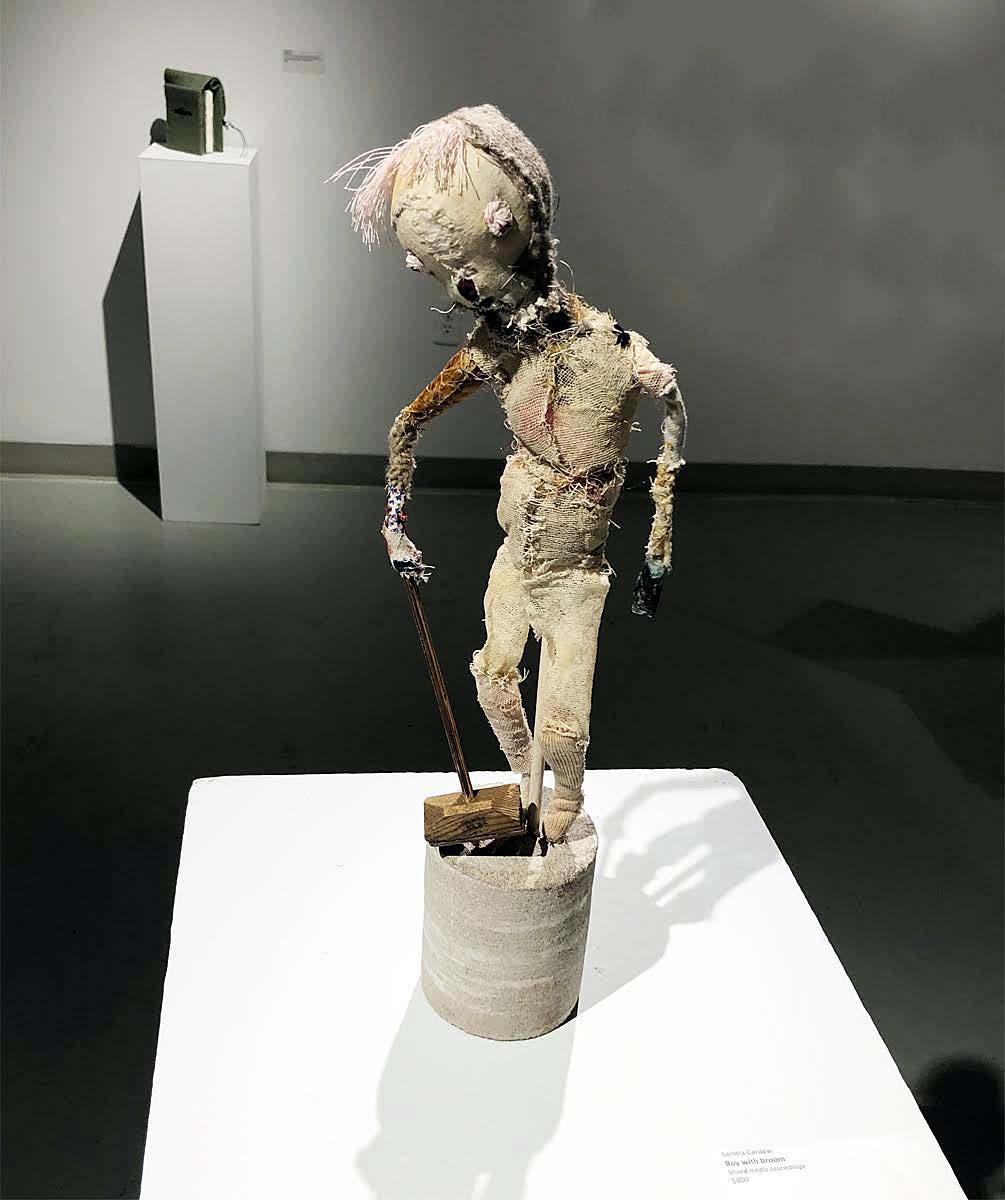

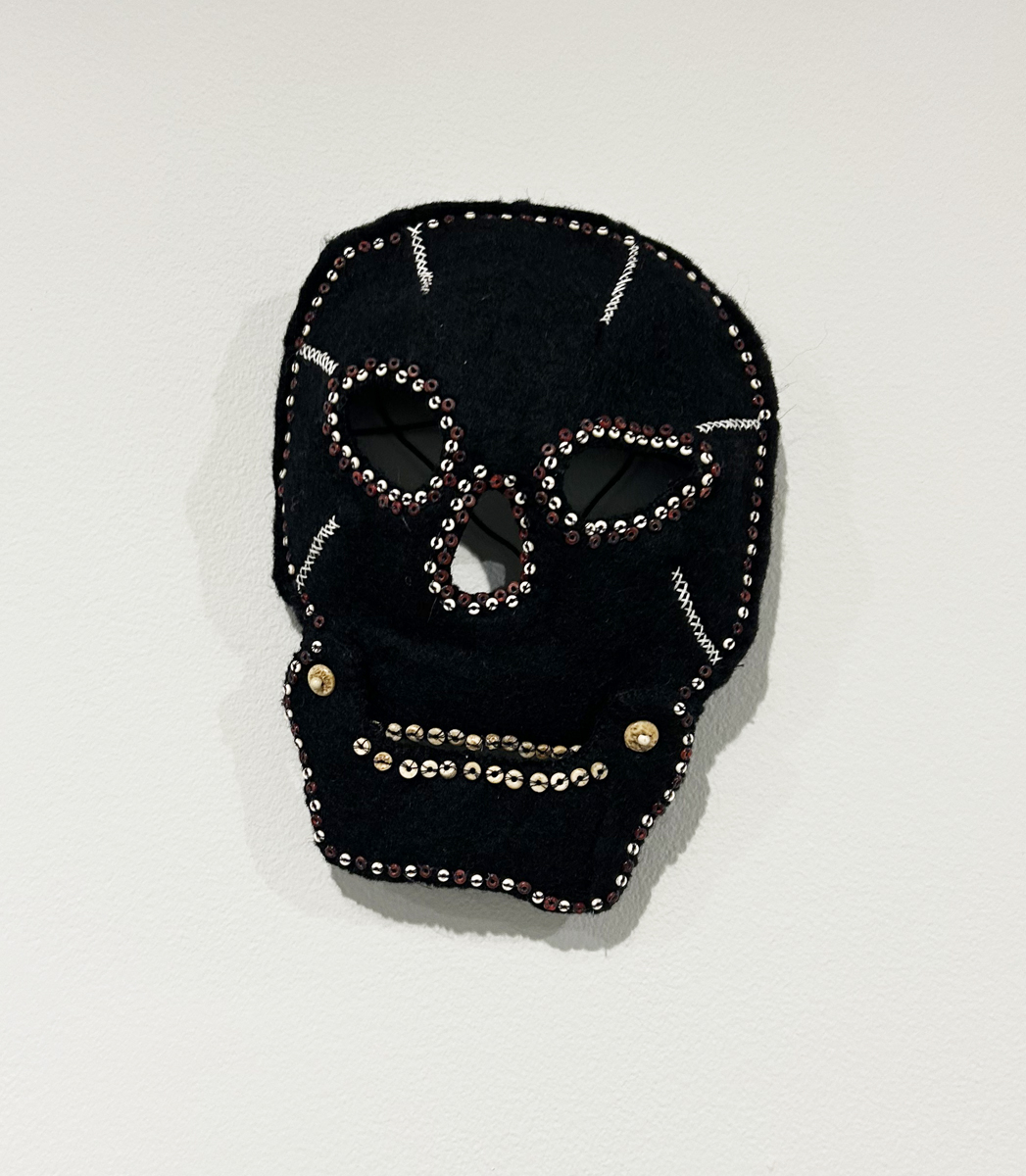

Mary Fortuna, Button Skull Mask, 2021, wool felt, buttons, embroidery.

Fortuna’s medium of choice is fiber and she is adept at manipulating the formal properties of fabric, beads and thread to produce a variety of appealing objects and images. She uses the submerged cultural references of stitched objects—toys, flags, masks–with the fluid ease of long practice to reveal hidden meaning. The emotional resonances of her carefully embroidered vintage linens, the creepy effect of her masks and hoods and the humor of her idiosyncratic insect dolls and baby devils show her to be not only a master of her medium, but also a virtuosic and subtle storyteller.

Mary Fortuna, Let it Be, 2018, embroidery on vintage textile.

These talents come together with particular force in Fortuna’s heartfelt grouping of embroidered vintage textiles that memorialize her recently deceased brother and sister. The artist remembers her brother Jon as a protector, an inventive playmate and a companion on innumerable camping trips; she has embroidered the two of them on vintage cloth with a tent in the background, together in memory. Fortuna commemorates the special bond she shared with her sister Mady in an embroidered image of the two children from a photo taken on the occasion of Fortuna’s First Communion. As is typical of much of her work, he identifies these images as ex votos, calling them “offerings to the universe on Mady’s behalf.”

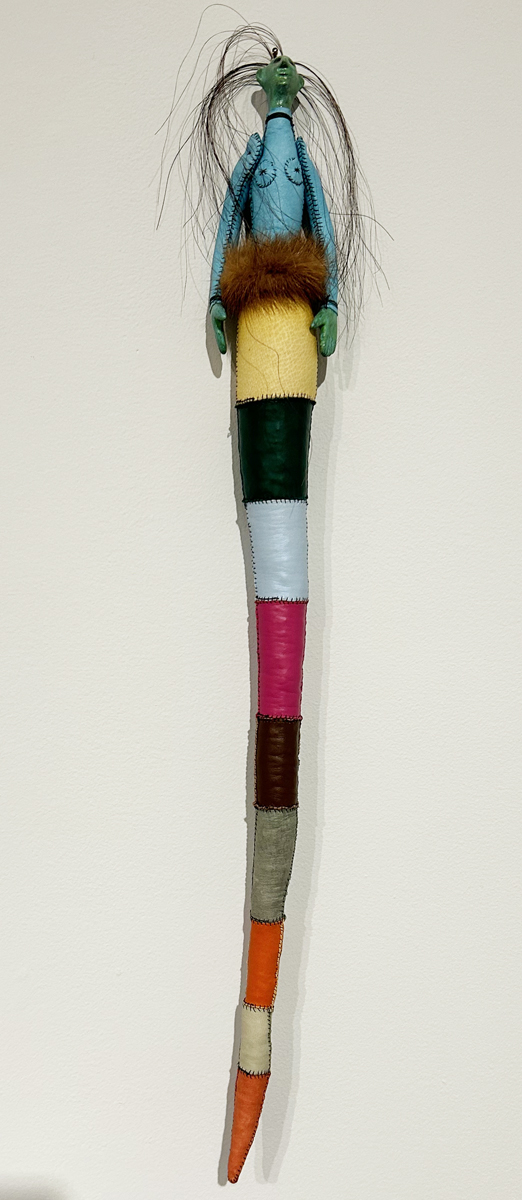

Mary Fortuna, Nageena, 2015, leather, fur, horsehair

The varied objects produced by Fortuna for this show are so uniformly well-conceived and executed that it would be hard to pick a favorite. But I was particularly drawn to Nageena, a soft sculpture that combines the charm of a doll that a child might play with and the subversive menace of a voodoo fetish. Typical of much of her work, Nageena combines cozy approachability with a slightly sinister subtext.

Adrian Hatfield

Hatfield, whose parents were scientists, remembers his rather specific childhood ambition to become “a vertebrate paleontologist or marine biologist.” Many of the images he incorporates into his paintings and installations come from early memories of comic book characters juxtaposed with figures from historical art sources.

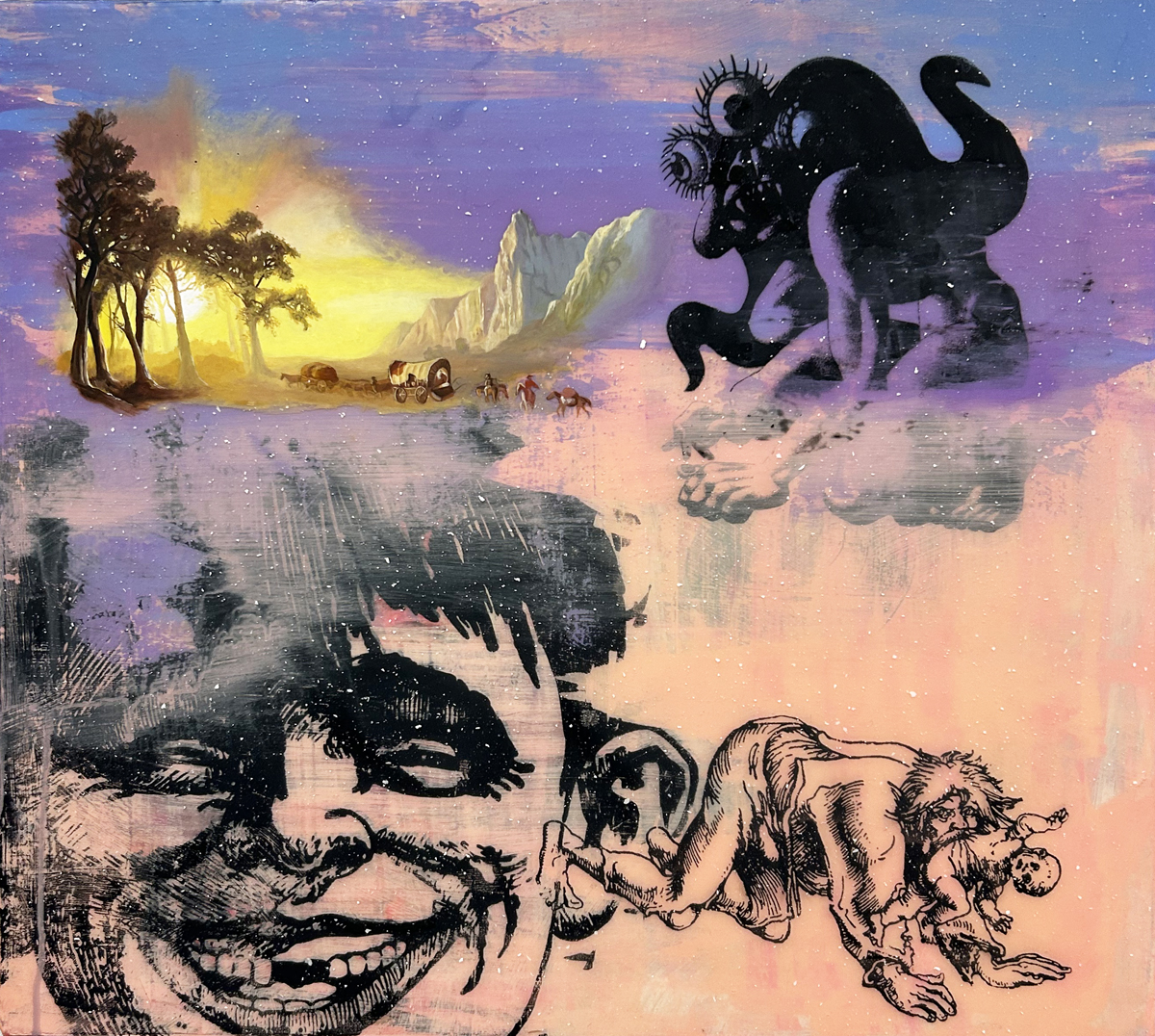

Adrian Hatfield, Manifest Destiny: there ain’t no party like a Donner Party, 2020, oil and acrylic on canvas.

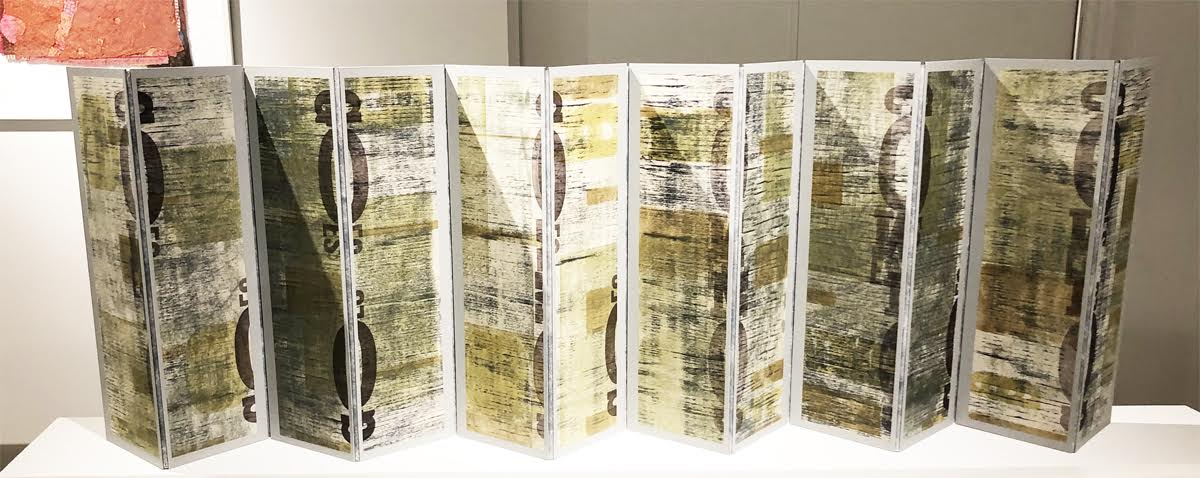

The scenes he creates are more assembled than painted, with elements of art history, vintage illustration and pop culture reproduced using photographic silkscreens and overlaid on large format canvases. Nineteenth-century Romantic landscape painting is referenced in the compositions by skillfully painted clouds, trees, and mountains rendered in acid pastels not found in nature.

Adrian Hatfield, Plotting happiness and flinging empty bottles, 2023, oil and acrylic on canvas.

Hatfield seems to have a particular fondness for the absurdist icon Alfred E. Neuman of Mad Magazine fame, whose face appears in several of the paintings in the exhibition. (Actually an earlier iteration of the famous nitwit which more closely resembles Hatfield’s version appeared in an 1895 ad for Atmore’s Mince Meat and Genuine English Plum Pudding. But I digress.) His gap-tooth visage sets a tone of absurdist catastrophe, undercutting and perhaps trivializing the ostensibly tragic themes. Disasters of all kinds and descriptions figure in the pictures, from the Donner Party to snakes attacking a man stuck in a barrel. The oversized face looking out idiotically from behind the picture plane seems to imply that the human race deserves its sad and silly fate.

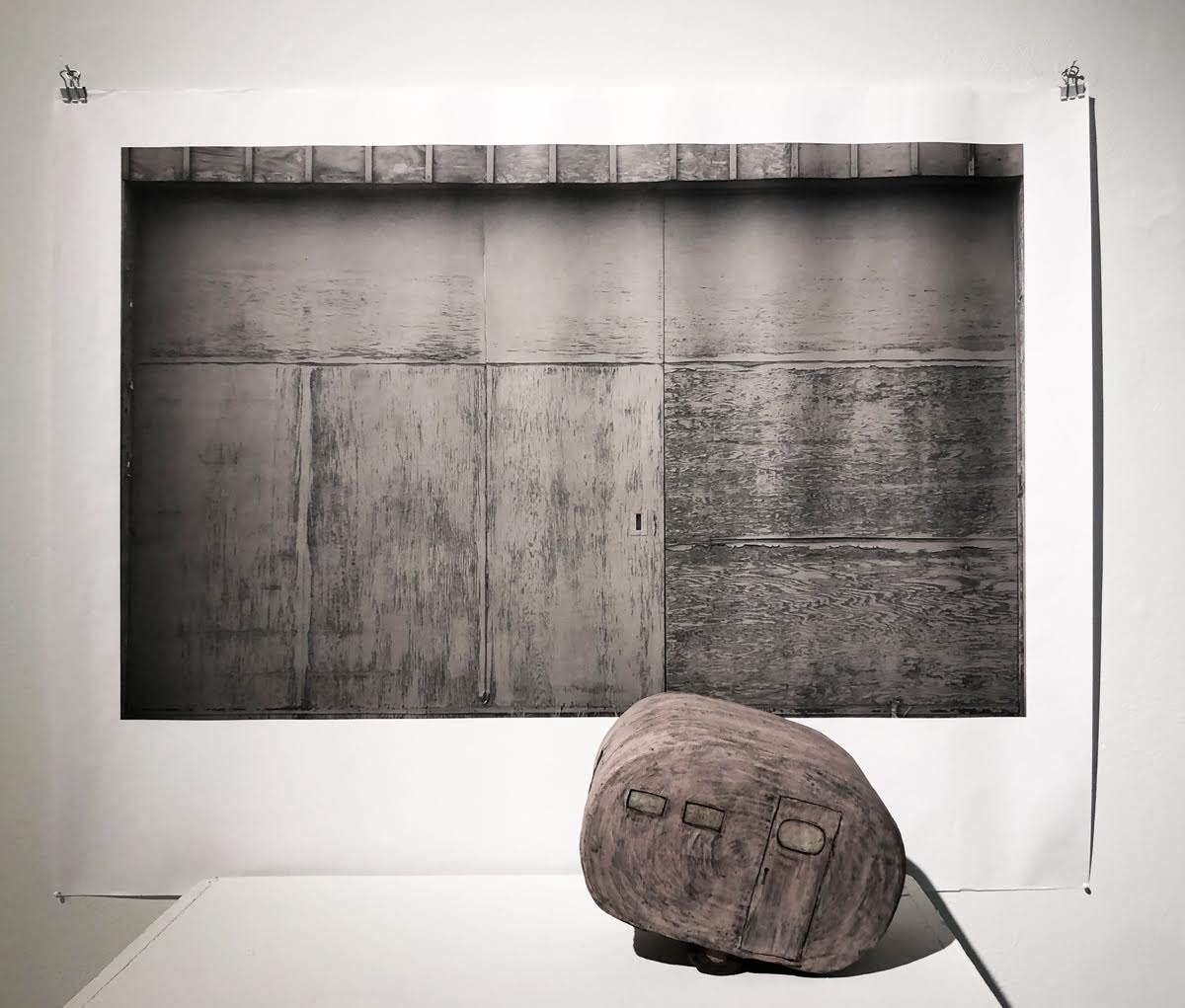

Adrian Hatfield, King of the Impossible, 2011, mixed media

On a more serious note, Hatfield references the Swamp Thing in his painting Plotting happiness and flinging empty bottles. The Swamp Thing was a comic book character that the artist remembers from his childhood, a scientist devastated by exposure to toxins that transform him into a creature composed of plant matter, who then becomes a tragic and heroic protector of the environment. Hatfield’s characteristic pastel underpainting is overlaid with black photographic depictions of a sinking ship and tire-filled toxic sludge from which the Swamp Thing emerges. The speech balloon in the upper center of the canvas remains empty. Could it be that in the face of disaster threatening human existence, we have no coherent response?

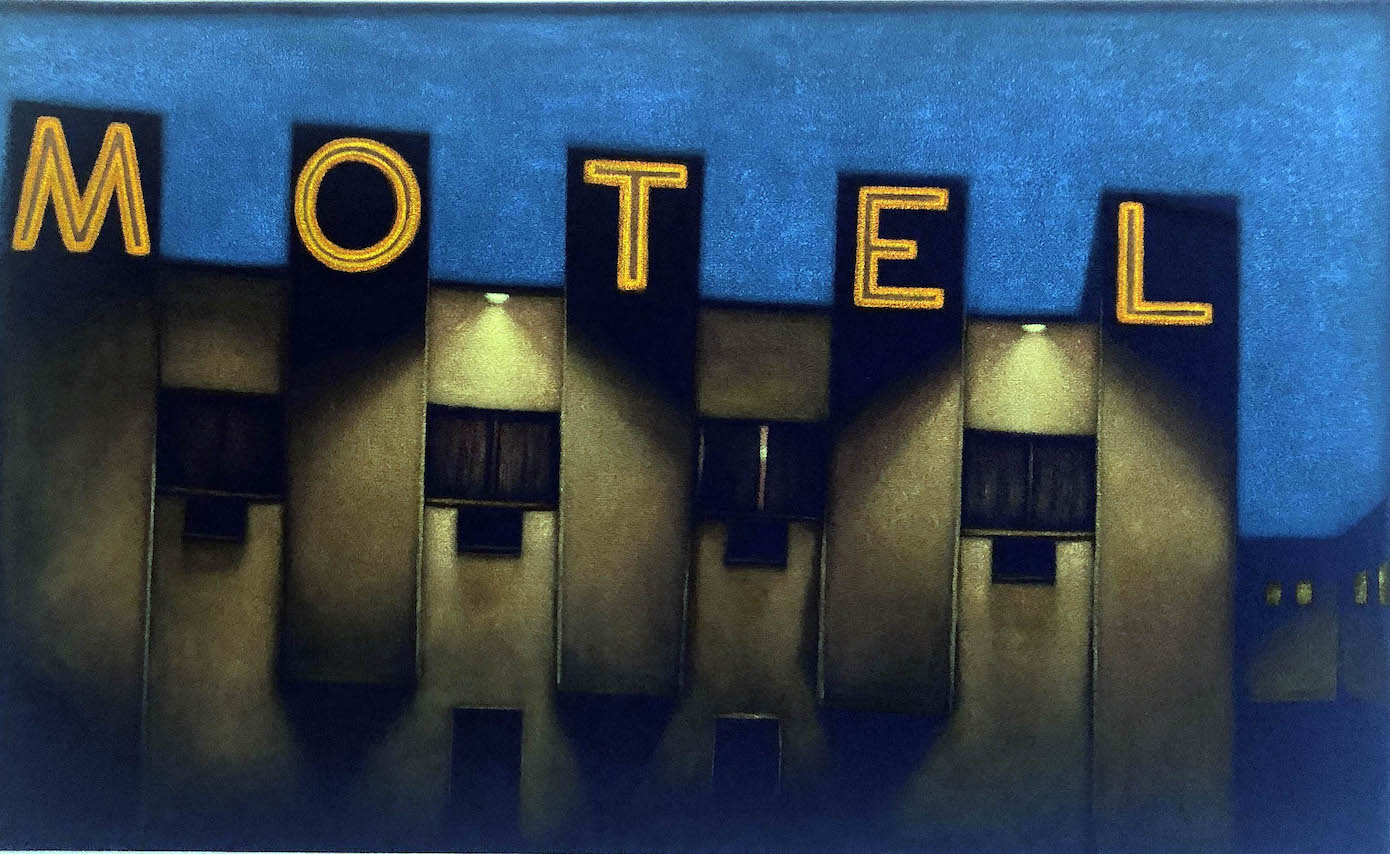

In a change of pace, Hatfield has created several dioramas in addition to his paintings. A notable example is his wall-mounted King of the Impossible which features a tiny half-figure—who might be the Invisible Man–on an elaborate decorative plinth overlooking a fantasy landscape, complete with a stegosaurus at one end of the scene and a tiny lambkin by a pool at the other. The rocky scene seems to float in mid-air, and the relationship of the figure above to the goings-on below is unclear, at least to me. Still, the whole thing is pretty entertaining.

The comic satire of Hatfield’s paintings moves us to both laughter and chagrin, while the emotional complexities of Mary Fortuna’s fabric creations gently and humorously remind us of our human connection. It’s clear that both artists have thought long and hard about where the human race has been and where it’s headed, and have come away with some serious reservations. But they also intuitively understand that it’s not the job of the artist to despair. Nostalgia and Outrage, instead, offers us hope against all odds, a feast for the eyes and food for thought in this wintry season.

Mary Fortuna and Adrian Hatfield @ Oakland University Art Gallery until March 24, 2024.