Kahlo Without Borders installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2022. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography

Everything changed for Frida Kahlo during a fateful bus ride through Mexico City in 1925. A few blocks from her school, where the 17-year-old Frida was a senior and exhibited precocious intelligence, the bus rounded a corner and collided with an oncoming trolley, severely injuring dozens of passengers. The wooden bus blew apart, leaving Frida with catastrophic injuries, including a steel rod that pierced through much of her body. She was pulled from the wreckage covered in gold dust, likely from a passenger who was an artist. She survived, defying the initial pessimistic assessment of the doctors at the Red Cross hospital. But much of the rest of her life was spent bedridden in hospitals in Mexico and the United States, where she underwent 32 surgeries. To pass the time, Frida began to paint.

Kahlo Without Borders at the MSU Broad explores Kahlo’s support network of friends and family, with a particular focus on the doctors she befriended during her many extended hospital stays. The exhibition is conceived as an intimate journey through a family scrapbook or photo album, and on view (for the first time, in some cases) are candid family photographs, letters, and even hospital records from the Kahlo family archives. This is an intimate and interdisciplinary show which traverses the boundary between the visual arts and the medical field, much like Frida Kahlo’s paintings.

Antonio Kahlo, Frida with cane, ca. 1950. Courtesy Cristina Kahlo and the Broad Art Museum

Kahlo was well-connected, and her social orbit encompassed many famous poets, artists, and writers. There are candid snapshots of Kahlo with muralist Diego Rivera, who Frida married, divorced, and re-married (theirs was an acrimonious relationship, but to the end they remained ardently supportive of each other’s career). We also see Kahlo with Leon Trotsky, a close family friend and, for a little while, Kahlo’s lover.

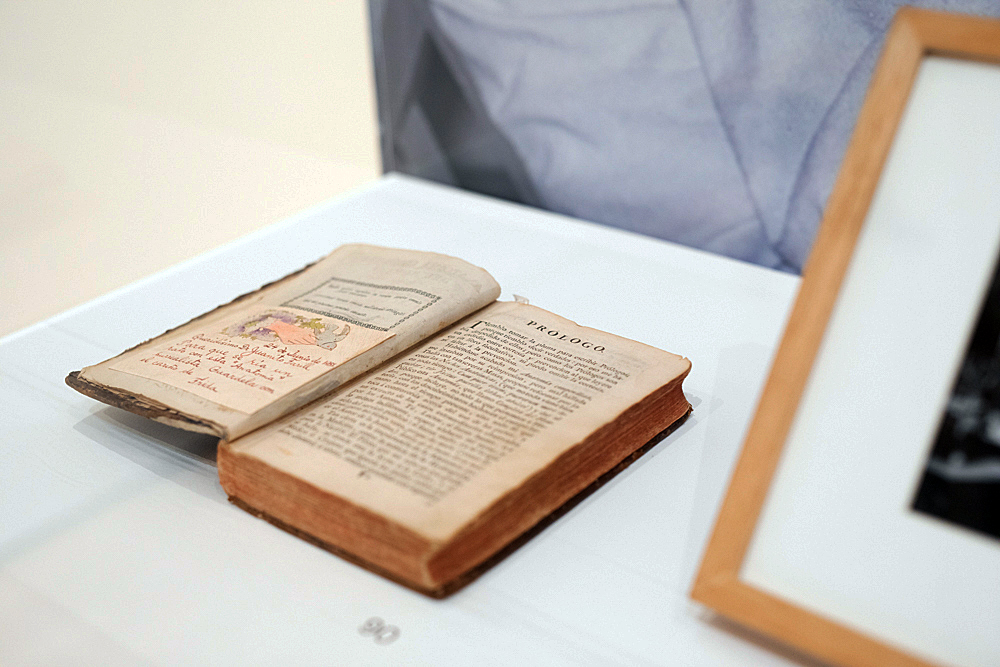

And, of course, we are introduced to a few of the doctors and nurses Frida Kahlo befriended, such as Leo Eloesser, Juan Farill, and Judith Ferrato. The letters and correspondence on view demonstrates the gratitude and affection Kahlo felt for these people. Kahlo featured Farill in her Self Portrait with the Portrait of Dr. Farill, and also gifted him a copy of the book The Complete Anatomy of A Man, which she accompanied with a note reading, “Dearest Dr. Farill. So you may laugh at the surrealist ‘Anatomy.’ Save it with Frida’s love.” Both the book and the note are on view.

Kahlo Without Borders installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2022. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography

Particularly moving are the photographs of Kahlo in hospital beds. Several of these show her working on various paintings, triumphantly affirming life in the midst of tragedy. But other images speak to the very visceral and unglamourous reality of her extended hospital stays. Into the 1950s, she appears visibly frail and worn, as in a picture captured by Raúl Anaya a few months before her death.

Kahlo Without Borders installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2022. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography

For Kahlo enthusiasts, the highlight of the show will certainly be the small ensemble of her original drawings, which include a pencil rendering of the 1925 tram accident, a subject she never actually painted. Two of these drawings were made in response to her second miscarriage, which occurred in Detroit while she was accompanying Diego, who was occupied painting his murals at the Detroit Institute of Art. One of these drawings, The Dream, visually anticipates the painting she would later make of the incident, Henry Ford Hospital: 1932. In both the drawing and the painting, a crumpled and visibly broken Frida lies naked, bleeding, and uncovered on a spartan hospital bed.

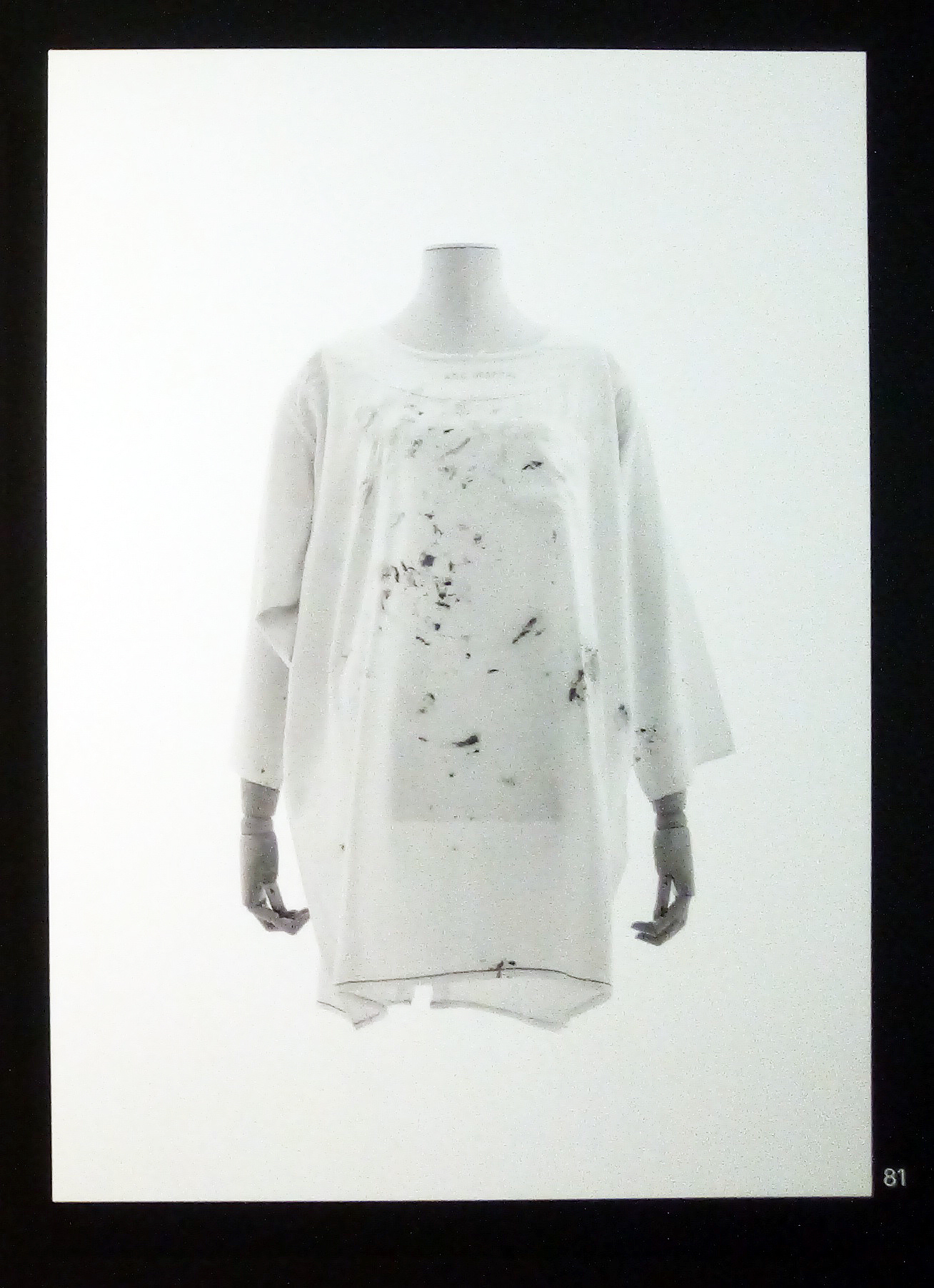

Kahlo’s grandniece, photographer Cristina Kahlo (who helped organize the show), lends contemporary insight into Frida’s life with a series of photographs that explore her stay at the American British Cowdray Hospital in Mexico City. An ensemble of photographs by Cristina shows the varied artifices and prosthetics that intruded into Frida’s body and art, such as her prosthetic leg and one of the corsets she had to wear. An ardent Communist, Frida personalized this particular corset with a hammer and sickle. In a large lightbox (mimicking a microfilm reader) we see actual records of Frida’s vital signs during some of her surgeries. Looking at a still frame from a monitor showing Frida’s heartbeat, one immediately recalls the many times Frida portrayed her heart in her paintings. Here, we can see its literal rhythm. Cristina Kahlo also photographed Frida’s hospital gowns which, as she painted, she would use to wipe excess paint from her brushes. Here, Cristiana Kahlo offers these images as an “absent portrait” of the artist.

Kahlo Without Borders installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2022. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography

This exhibition is a must-see for Frida Kahlo fans. As for the uninitiated, this show might come across as visually thin, given the prevalence of letters and correspondence. But it’s certainly thematically compelling. Perhaps it’s cliche to say of Frida Kahlo that, phoenix-like, she harnessed personal tragedy as the source of life and beauty. Then again, Kahlo’s art certainly isn’t beautiful. But it’s always eloquently and gut-wrenchingly truthful, speaking to the pain we all inevitably face at one time or another. And as for Frida, the portrait that emerges between the lines suggests that in spite of everything she endured, she possessed an indefatigable fortitude, a zest for life, and a deep affection and gratitude for her support network. Whether or not you’re a fan of Frida Kahlo’s art, her spirit is inspiring, and Kahlo Without Borders serves as an affectionate and personal tribute.

Kahlo Without Borders installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2022. Cristina Kahlo, Absent Portrait 1 (2016)

Kahlo Without Borders is on view at the MSU Broad through Aug. 7, 2022.