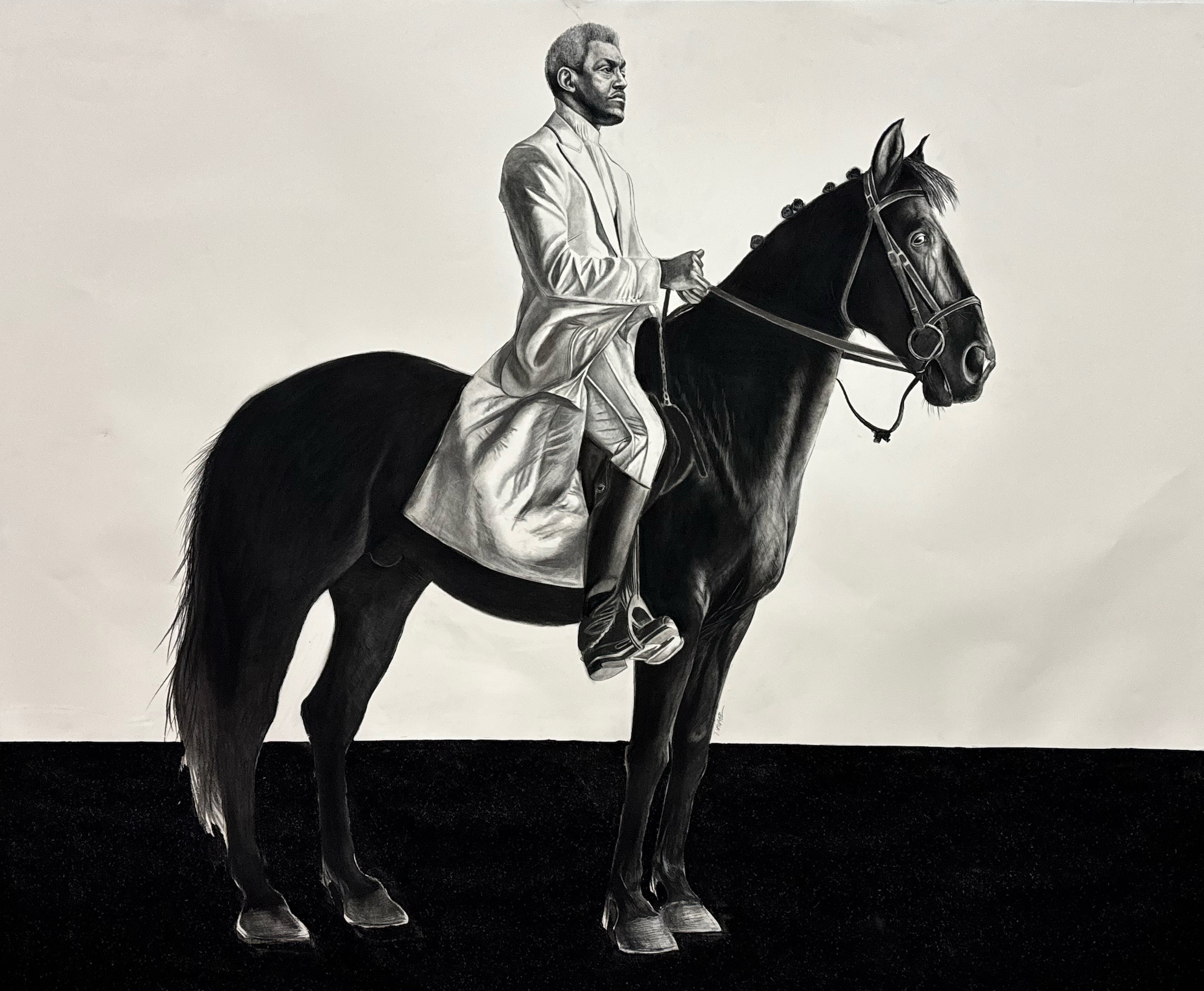

Tylonn J. Sawyer, Black Man on a Horse: Bayard, 2024, charcoal, pastel and glitter on paper,72” x 88.5” All Photos courtesy of David Klein Gallery

The 21 artists whose work is on view at David Klein Gallery right now can tell you—and show you–that drawing has its own special kind of magic. “Nothing up my sleeve here,” these creatives seem to say as they produce, with a flourish, images conjured from imagination and a few rudimentary materials. As individual as a fingerprint, each artist’s contribution defines, and sometimes expands, our understanding of what a drawing can be and do.

Tylonn J. Sawyer’s life-size equestrian figure Black Man on a Horse: Bayard, anchors the exhibition and is very much front and center. The image depicts civil rights hero Bayard Rustin astride a barely controlled horse that may leap off the wall at any moment. The charcoal on paper drawing invites comparison to Kehinde Wiley’s Officer of the Hussars (2007) at the Detroit Institute of Art but switches out that painting’s pretty fussiness for austere formal and emotional rigor on themes of Black history and identity. The addition of a field of black glitter at the lower portion of the composition adds a mythic edge.

Cydney Camp, Friendly Place, 2024, graphite on paper, 36” x 36

Many of the portrait drawings in the exhibition are life-size or larger. Kim McCarty’s faces of young women, Charles Edward Williams’s handsome swimmers, Cydney Camp’s Friendly Place and Whitfield Lovell’s Spell #16 demand our attention with their scale and skill. Panning out from the close-up view, Robert Schefman and Joel Daniel Phillips include drawings of single figures that place their subjects within a specific time and place for added context.

Marianna Olague, Head Over Heels, 2024, graphite, gouache and colored pencil on paper, 30” x 22”

Several of the large figurative portraits depend upon unorthodox points of view to capture our interest. Conrad Egyir’s recessive figures turn away even as he uses the tools of their creation, arranged on shallow ledges below the images, to draw us in. Kelly Reemtsen, as usual, focuses on the implied social status of her fashionable ladies and the subtle menace of their sharp tools. Marianna Olague literally turns self-portraiture on its head with a drawing of sneaker-clad feet seen from below, as if she is taking a selfie while lying on her back.

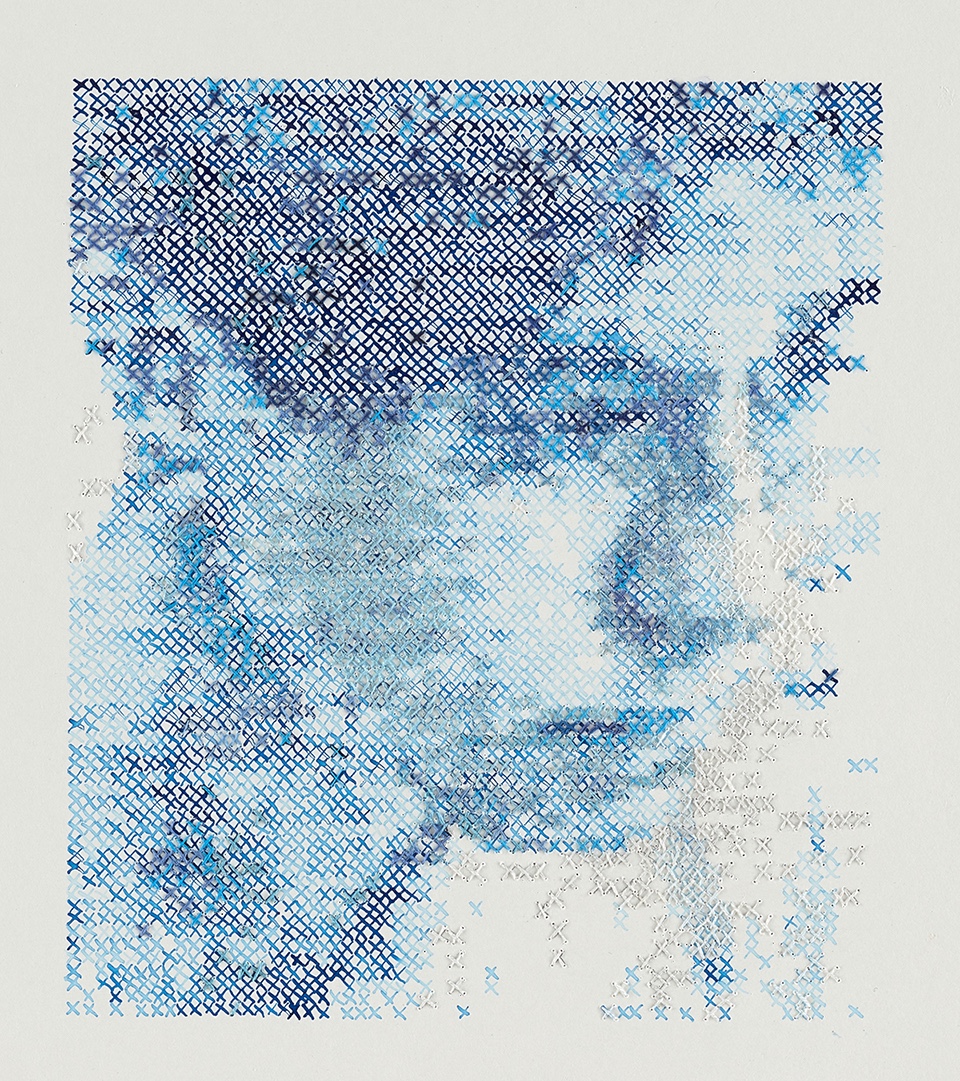

Cayce Zavaglia, Raphaella Blue Cross-Stitch, 2021, ink and hand embroidery on Arches paper, 15” x 11”.

A number of the most impressive still-life drawings depend upon their large scale for impact. Jessica Rohrer’s breathtakingly intricate Red Coleus invites close looking; it irresistibly draws the viewer into a close inspection of the minute red and purple leaves within the magnified whole. Armin Mersmann’s imposing—and decomposing—giant pear is another spectacular example of how scale can be employed to capture our attention.

Mary-Ann Monforton, Red Chair, 2023, watercolor and pencil on paper, 11” x 8.5”

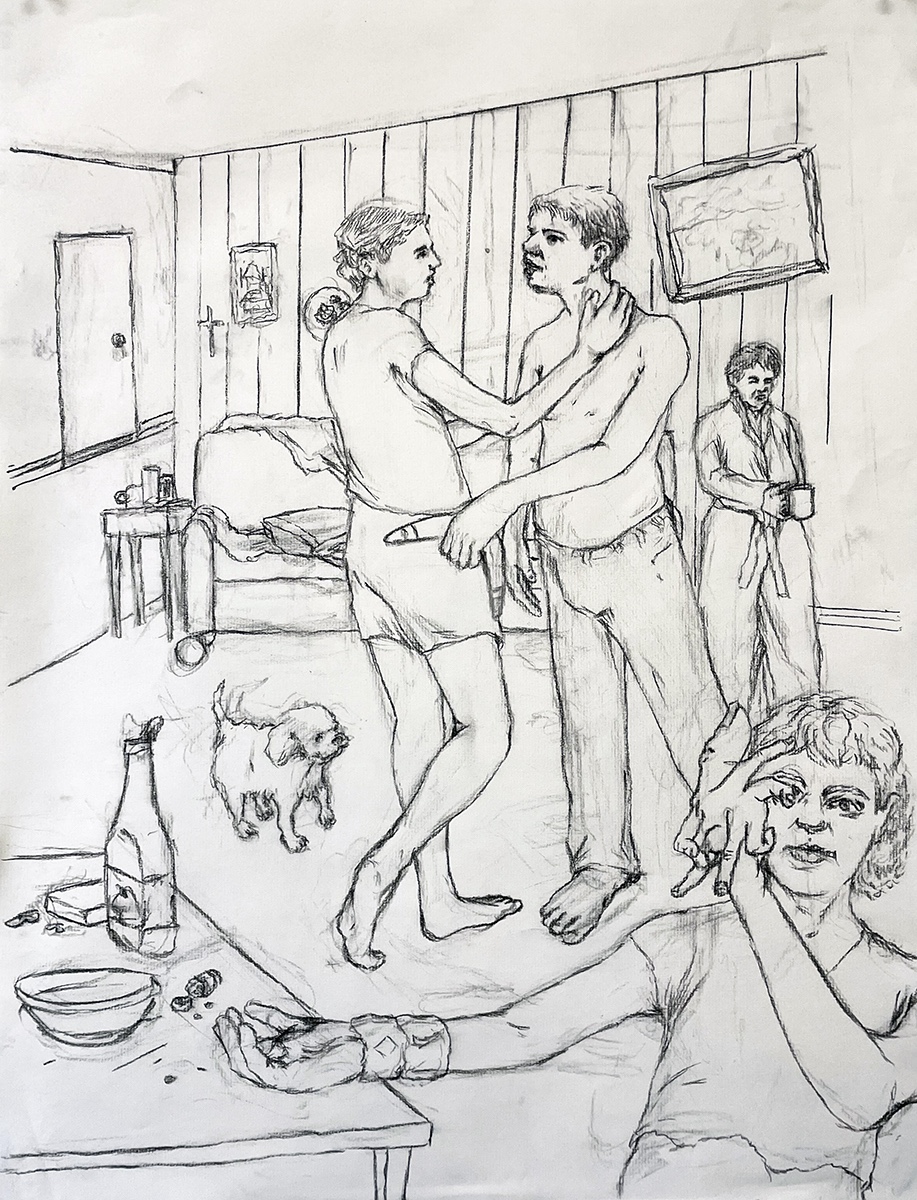

But large formats don’t entirely dominate. Shea Burke’s sweetly intimate watercolors and Cayce Zavaglia’s embroidery on paper, Raphaella Blue Cross-Stitch, ably make the point that a drawing needn’t be large to be impactful. Maryann Monforton’s quirky colored pencil drawings invite us into her cozy, art-filled home, where her friendly, funny chairs and snack-laden plates offer hospitality on paper. Willie Wayne Smith’s improvised interior, Boomerang, suggests a situational mystery and raises more questions than it answers. Jack Craig’s finely detailed pencil drawings appear at first to be abstractions, but upon close inspection turn out to accurately reflect his three-dimensional freeform bronze constructions.

Willie Wayne Smith, Boomerang, 2019, charcoal on paper, 24” x 18”

Though the exhibition belongs (mostly) to the figurative realists, a few very welcome abstract drawings make the curatorial cut. Neha Vedpathak’s light and air-filled Untitled Drawings #1, #2 and #3, with their delicate but insistent marks in metallic dust, charcoal powder, graphite and acrylic, seem to levitate just in front of the paper. In contrast, Susan Goethel Campbell’s dark, pierced and stained Night Garden builds upon the themes of her recent solo show at the gallery with moody intensity. Benjamin Pritchard’s paper and ink collage, Night Shapes, is a special visual treat. The dreamlike architecture of geometric shapes and symbols is both weighty and weightless, simple yet enigmatic. Are there more of these beauties lurking somewhere in his studio? I hope so.

Benjamin Pritchard, Night Shapes, 2021, ink and collage on Arches paper, 42” x 39”

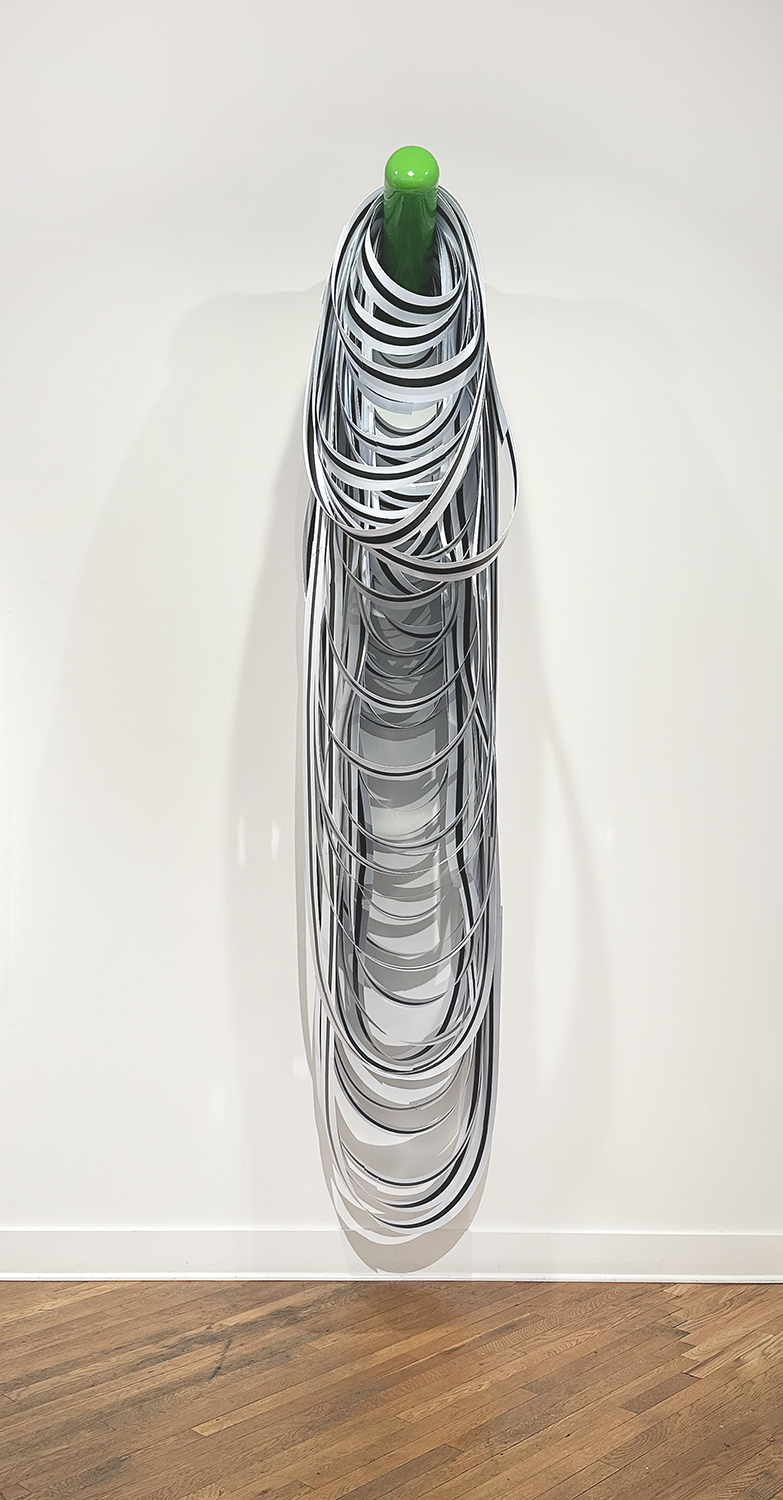

Perhaps the most physically imposing—and formally complex—piece in “Drawing: Detroit, A Line Goes for a Walk” is Emmy Bright’s Big Drawing which combines printmaking, sculpture, conceptual art and assemblage. It is all—and none—of the above. Bright, an artist in residence in print media at Cranbrook Academy of Art, repeats a single line printed on paper many times, then attaches the papers end-to-end to form a bale (A bunch? A bundle?) that hangs on a metal peg on the gallery wall.

The art and craft of drawing represents a core competency for most artists and certainly of the artists in this exhibition. “Drawing: Detroit” offers gallery visitors an eclectic mix of works on paper that combine impressive technical mastery with considerable conceptual interest. These artworks on paper, made by some of the city’s most accomplished practitioners, will be on view until March 15, 2024.

Emmy Bright, Big Drawing, 2023, polystyrene grommets, acrylic, steel peg, variable dimensions.