Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898 -1971 features nearly 200 historical items – including photographs, film clips, costumes, props, and posters.

Installation image at the entrance to the exhibit. Image courtesy of DAR. All other images courtesy of the Detroit Institute of Arts.

The Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) opened a new exhibition, Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898-1971, a landmark exhibition exploring the profoundly influential yet often overlooked history and impact of Blacks in American film from cinema’s infancy, as the Hollywood industry matured and the years following the Civil Rights Movement. The exhibition, originally organized by the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, will also include a new, unique film series in partnership with the Detroit Film Theatre.

“We are honored to present Regeneration, a powerful, inspiring, and important exhibition that examines the rich and often untold history of Blacks in American cinema,” said DIA Director Salvador Salort-Pons. “The exhibition explores the critical roles played by pioneering Black actors, filmmakers, and advocates to shape and influence U.S. cinema and culture in the face of enduring racism and discrimination.”

Dancers Performing the Cake Walk, 1887. Gelatin Silver Print. Culver Pictures. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Photographs & Print Division. The New York Public Library.

The exhibition opens with early cinema and explores moments of progress as other forms emerged in the early 1900s despite the prevalence of racism that permeated the culture. Many Black artists appeared in blackface and played roles subservient to their skills and interests. Performers like Bert Williams and Sam Lucas found work on stage that did not represent their full humanity in the roles cast would depend on adapting to racist tropes. The exhibition includes Newsreels. Home movies, excerpts from narrative films, documentaries, and a selection of fully restored, rarely-seen films amplify African American contributions to the history of cinema in the United States.

Excerpt from Something Good, Negro Kiss, 1898, Director Nicholas Selig, the National Library of Norway.

“This critically important presentation chronicles much of what we know on-screen but shares so much more of what happened off-screen,” said Elliot Wilhelm, DIA Curator of Film. “Our community will learn how each generation of these pioneering actors and filmmakers paved the way for the following generation to succeed and how they served as symbols and advocates for social justice in and beyond Hollywood. The museum’s beautiful Detroit Film Theatre will help further share this history with a wide-ranging film series that ties together the exhibition and Detroit’s cinema history.”

Lime Kiln Club Field Day, Excerpt for the film, Museum of Modern Art. 1913. American black-and-white silent film produced by the Biograph Company and Klaw and Erlanger.

This archival assembly of one of the oldest surviving silent-era films featuring an all-black cast was created by the Museum of Modern Art in New York after seven unedited film reels were discovered in its collection. Based on a popular collection of stories, Lime Kiln Club Field Day features Black stage performer Bert Williams, actor Abbie Mitchell, and hat designer Odessa Warren Grey; many cast members were recruited from the popular Harlem Musical Darktown Follies.

Among the artifact highlights on view, Regeneration presents home movie excerpts of legendary artists such as Josephine Baker and the Nicholas Brothers; excerpts of films featuring Louis Armstrong, Dorothy Dandridge, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Sidney Poitier, Paul Robeson, Cicely Tyson, and many others.

Installation image, Opening room to the exhibition. Detroit Institute of Arts. 2024

The famous contemporary Artist Kara Walker presents the viewer with The End of Uncle Tom and the Grand Allegorical Tableau of Eva in Heaven, created using cut paper and adhesive on the wall, which stretches out 35 feet long. Her well-known silhouettes recall and interpret the trauma of slavery, restating historical memory and forcing the viewers to bear witness to her world of racial oppression and suffering on pre-Civil War plantations. The curators from the Academy of Motion Pictures in the image above are, starting from the left: Doris Berger, Co-Curator of Regeneration; Jacqueline Stewart, Director and President of the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures; and Rhea Combs, Co-Curator of Regeneration. The first exhibition of Regeneration opened in Los Angeles as part of its parent institute, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

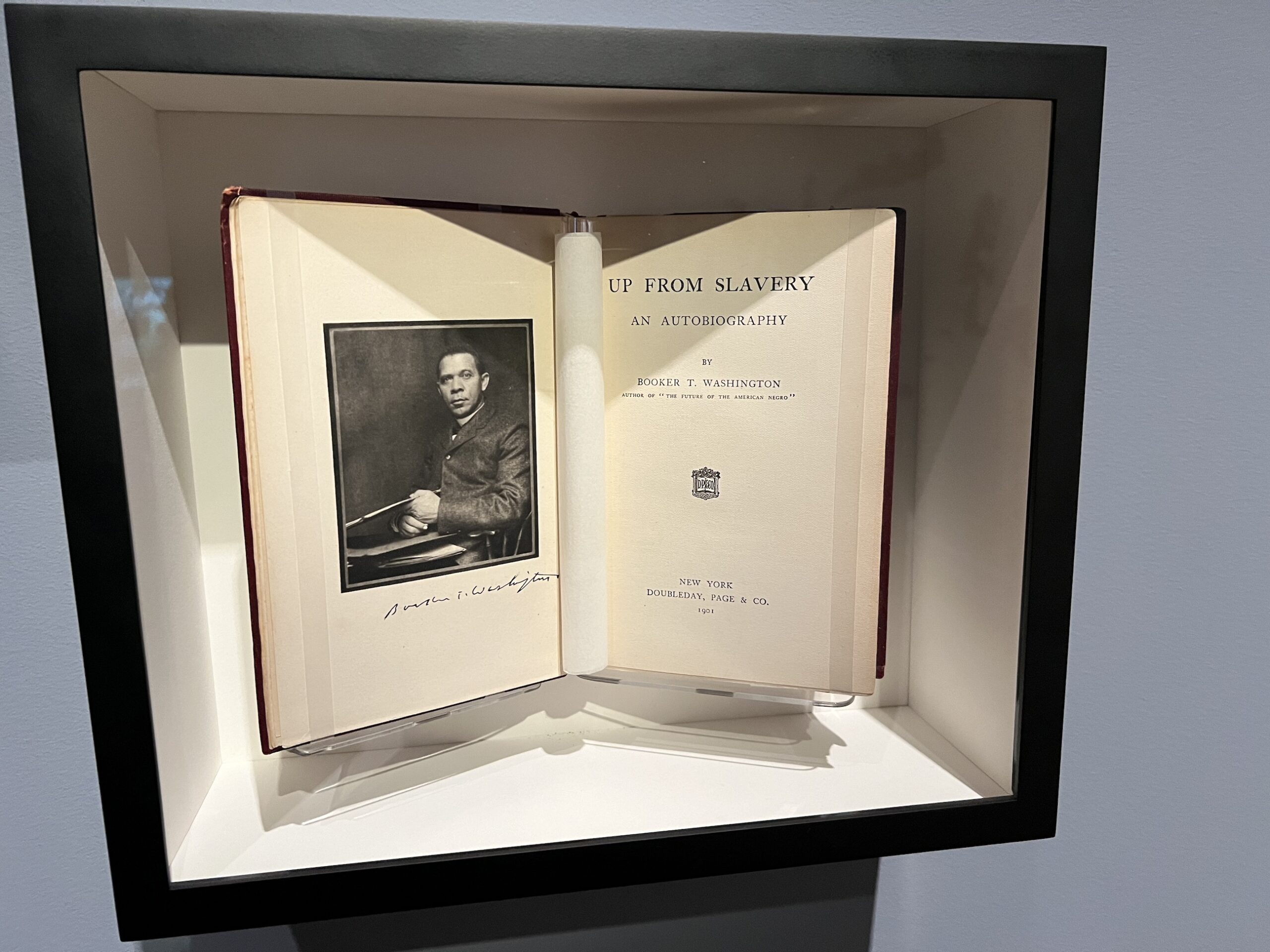

Image from Up From Slavery, An Autobiography, Booker T. Washington. 1901.

Up From Slavery by Booker T. Washington is the 1901 autobiography of the American educator Booker T. Washington (1856–1915). The book describes his experience of working to rise up from being enslaved as a child during the Civil War to help Black people and other persecuted people of color learn helpful, marketable skills and work to pull themselves, as a race, up by the bootstraps. He reflects on the generosity of teachers and philanthropists who helped educate Black and Native Americans and describes his efforts to instill manners, breeding, health, and dignity into students. Washington explained that integrating practical subjects is partly designed to “reassure the White community of the usefulness of educating Black people.”

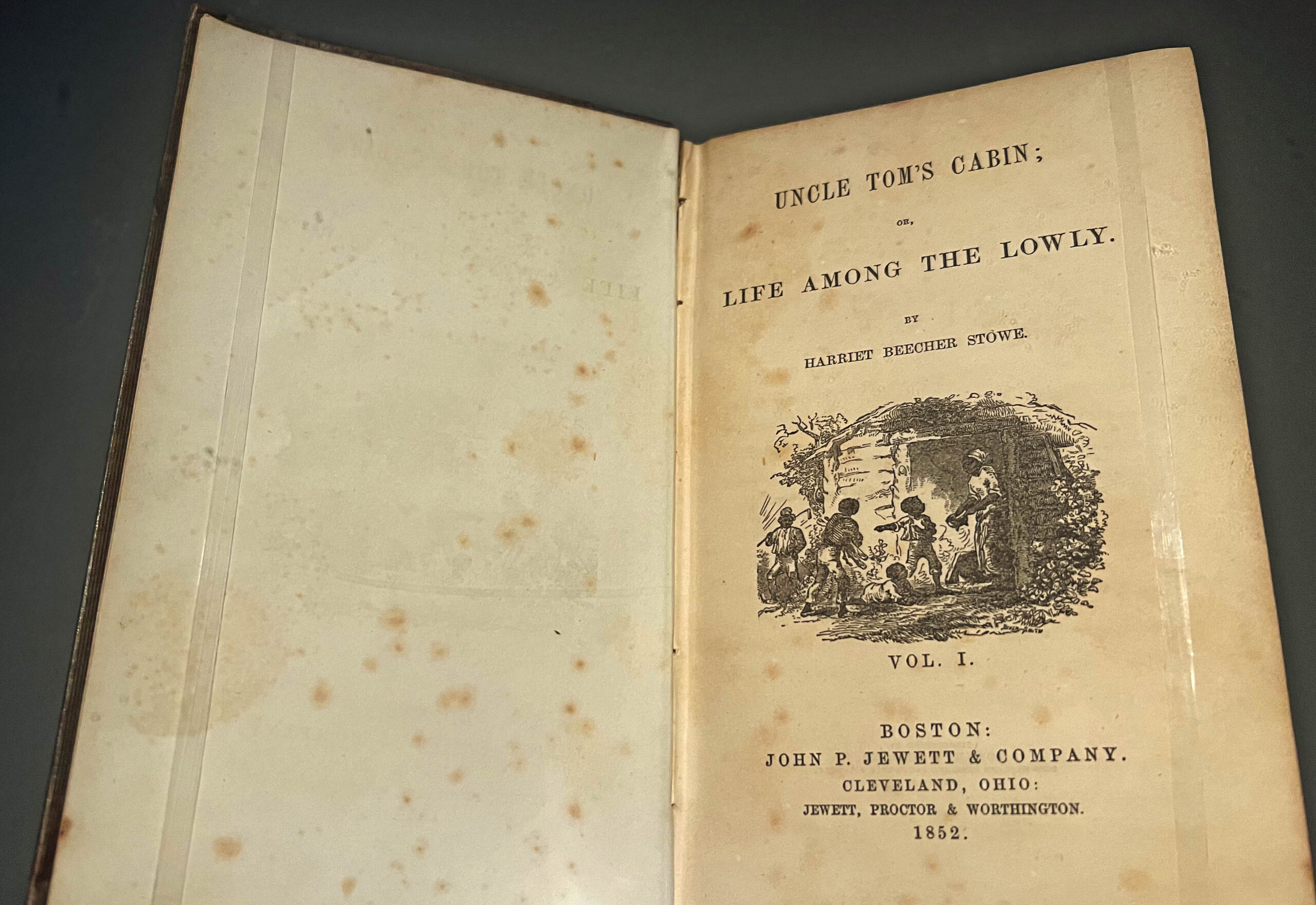

Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Life Among the Lowly, Harriet Beecher Stowe, 1852. Published by John P. Jewett and Company.

One of many artifacts in the exhibition is the famous book Uncle Tom’s Cabin, an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe, which is said to have “helped lay the groundwork for the American Civil War.” Stowe sent a copy of the book to Charles Dickens, who wrote her in response: “I have read your book with the deepest interest and sympathy, and admire, more than I can express to you, both the generous feeling which inspired it, and the admirable power with which it is executed.” Some modern scholars criticized the novel for condescending racist descriptions of the black characters’ appearances, speech, and behavior, as well as the passive nature of Uncle Tom in accepting his fate.

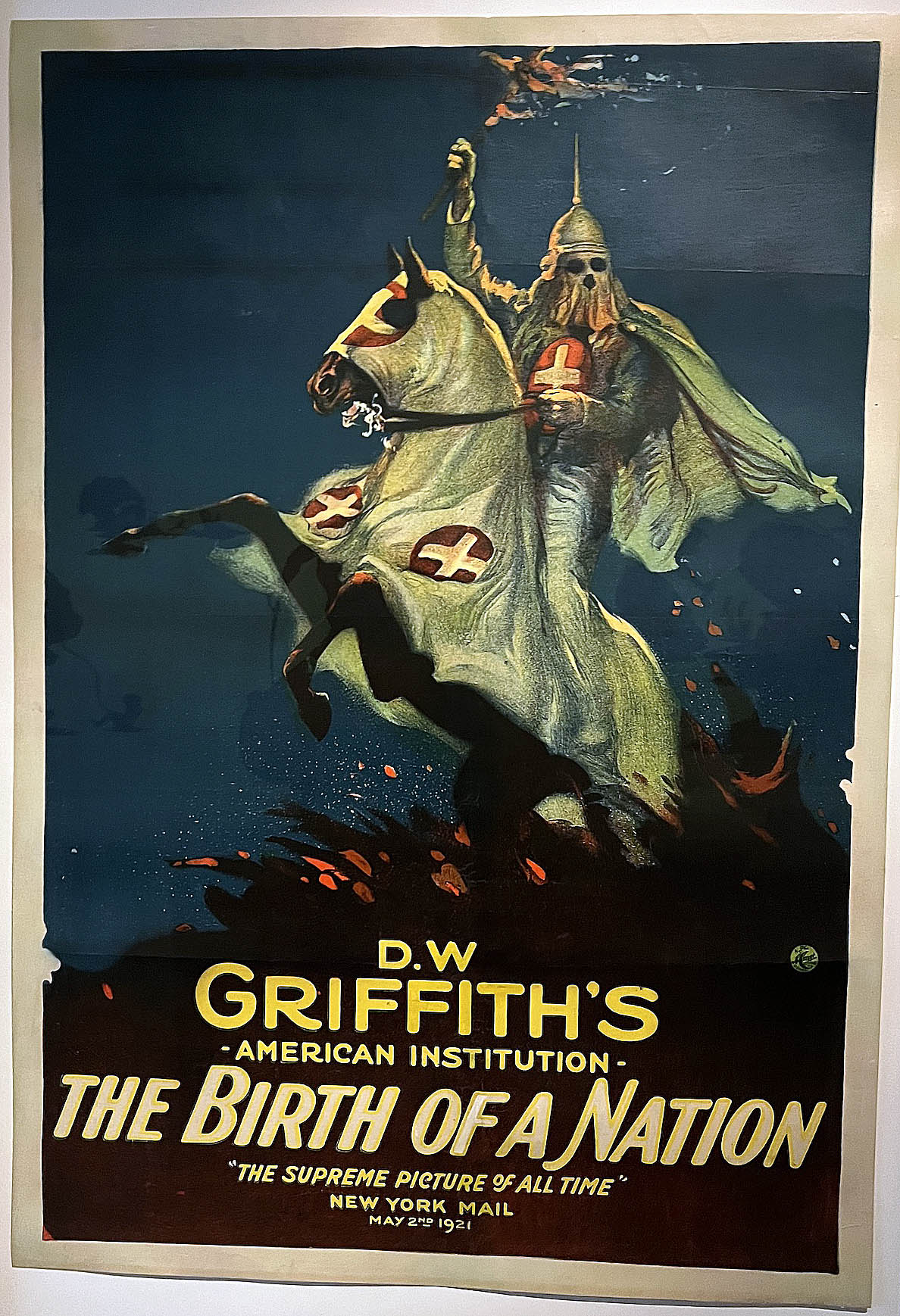

Movie Poster, D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, Epoch Producing Co. 1915.

The film made in 1905, The Birth of a Nation, is a landmark silent epic film directed by D.W. Griffith. Its plot, part fiction, and part history chronicles the assassination of Abraham Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth and the relationship between two families in the Civil War. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) is portrayed as a heroic force necessary to preserve American values, protect white women, and maintain white supremacy. The story that many recall is that Birth of a Nation was the first motion picture to be screened inside the White House, viewed there by President Woodrow Wilson, his family, and members of his cabinet.

Installation image, Early Movie Posters

The exhibition Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898-1971, now at the Detroit Institute of Arts, came from Los Angeles and was organized by the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in 2022 to help people fully understand how people of color participated in the motion picture industry from the very start.

Seeing this exhibition is the perfect experience for the people of Detroit to take their family to the DIA (at no cost to those living in Wayne, Oakland, and Macomb Counties) to view the chronology of events as they unfolded despite the challenges of reconstruction and the everlasting racism that permeated the culture for a century. The DIA is the first stop; in an attempt to educate people across the country with truth, facts, and evidence, this exhibition is bound to make an impression. It is critical today, more than ever, that we embrace our history. In current events across the country, there are plans to erase black history forever. At last count, 44 states have started debating whether to introduce bills that would limit what schools can teach about race, American history, gender identity, and sexual orientation.

One of the most articulate writers on this topic is James Baldwin, who writes, “It is the utmost importance that a black child sees on the screen someone who looks like him or her. Our children have suffered from the lack of identifiable images for as long as they were born. History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history.”

Museum Hours – Tuesdays – Thursday- 9:00am – 4:00pm

Friday – 9:00am – 9:00pm

Saturday – Sunday – 10:00am – 5:00pm