Laurie Tennent, Giant Fern, 30 x 135″, Polychrome on Aluminum, 2016

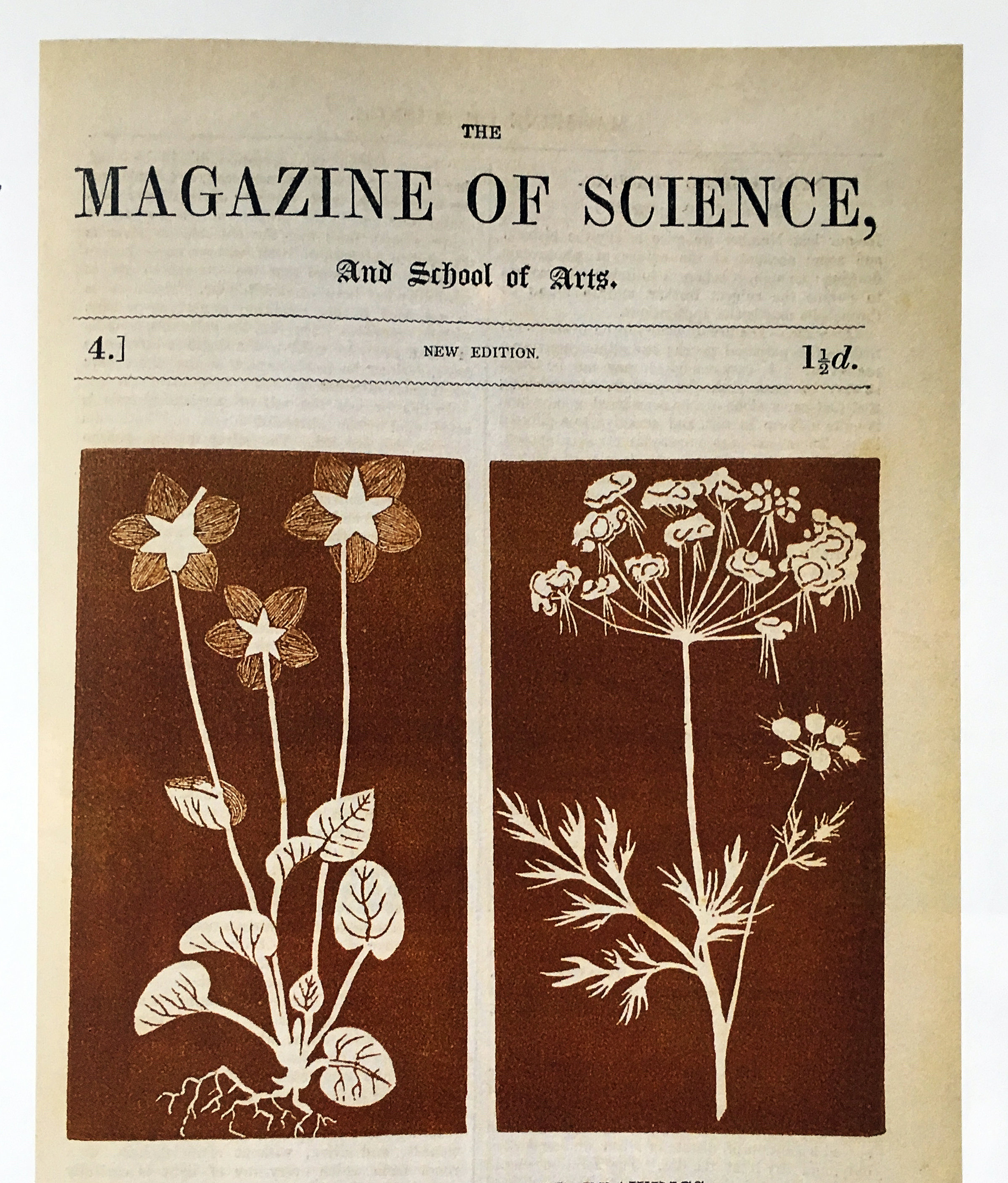

One of the oldest surviving photographic images, a daguerreotype still life from 1839, carefully depicts objects made of plaster cast sculptures and a wicker-wrapped bottle. In that same year, William Henry Talbot created a photo image of a leaf, Leaf with Serrated Edge, by placing a plant leaf on a piece of light-sensitive paper before exposing it to a light source. Later, that same year, the Magazine of Science published photograms from work by Anna Atkins that were botanicals placed directly on photosensitive paper.

Magazine of Science, School of Art, William Talbot samples, London, 1839

Anna Atkins, Poppy, Cyanotype, Vitoria & Albert Museum, London, 1839

From those beginnings through the following 160 years we have seen photography develop in myriad ways, which brings me to the current exhibition of photography at Oakland University Art Gallery, Hiberna Flores, by Laurie Tennent. The Birmingham, Michigan-based commercial photographer has worked hard to produce a body of work comprised of botanically-based images. These relatively large-scale photographs (40 X 72”) are digital images printed on aluminum. One assumes they are real plant objects set up in a studio and captured with a large format camera that sits on a tripod, providing the artist maximum control over focus and exposure.

She says in her interview, “Complexity of character, masculine and feminine, intimate yet bold, sensual yet strong: My photographs are an exploration of these dualities. By exaggerating the inner architecture of plant life, I offer the viewer a chance to at once become confronted by and immersed in nature.”

Laurie Tennent, Oriental Poppy, 36 x 70″, Polychrome on Aluminum, 2014

While many photographers are shooting events, people, fashion, cars, wars and outer space, there are photographers who have devoted parts of their careers to capturing flowers. In the late 1980s Robert Mapplethorpe devoted part of his oeuvre to capturing botanicals in both black and white and color. They often get overlooked in his total body of work because of his focus on the fetish, but they stand out elegantly in composition and scale. Around that same time, in the mid-1980s, Bulfinch Publishing released Harold Feinstein’s book, 100 Flowers. Feinstein was the first to use a scanner as his camera. His work was covered by Life magazine and received a Smithsonian Award for digital photography in 2000.

But Tennent brings her signature to her work primarily in her selection of plants and her approach to the composition. The image, Oriental Poppy (36 X 70”, 2014) produces a feeling similar to Grande Odalisque, by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, the French Neoclassical painter, 1819. Soft light stretched out on this horizontal botanical composition against a black background creates a similar feeling in the experience of the viewer: How beautiful!

For this review, I asked Tennent a few questions:

Ron Scott – How did you get interested in photography, early on?

Laurie Tennent – My interest in photography started in high school with a love of science and biology. After an introduction to College for Creative Studies, I decided to pursue photography. It was the darkroom that really amazed me.

RS – What lead you to fine art photography?

LT – Having an education in both fine art and commercial photography, I have practiced both for over 30 years. After college, I worked in the gallery business first at the Rubiner Gallery then opened The Eton Street Gallery in Birmingham, Michigan. To support the gallery, I worked in the fashion and commercial photography business.

RS – How would you describe the technical approach in capturing and printing these images (what degree of post production in the work is done)?

LT – All of the images are created in the studio. Plants and botanical specimens are photographed with digital capture and then dust and pollen are removed in post. They are printed on aluminum with a heat transfer process called dye sublimation. I only print a limited edition of 5 to 10 prints of each image.

RS – What photographers (past and present) influenced your work?

LT – Locally, my mentors are Balthazar Korab and Bill Rauhauser. Korab made a huge impression on me with his work ethic and ability to blur the lines between fine art and commercial images. Rauhauser was my professor and thesis advisor at Center for Creative Studies. His knowledge of history and passion for photography is infectious. In addition, I was also influenced by the work of Imogen Cunningham for the pattern and detail in her photographs and the sculptural scientific images of organic structures by Karl Blossfeldt .

Laurie Tennent, Kalanchoe, 40 x 60″, Polychrome on Aluminum, 2016

With an acute sensitivity to today’s persistent digital noise, Tennent’s collection of intimate portraits commands attention by returning us to our most primitive and organic roots. Isolating delicate living structures and amplifying them on a massive scale transports the viewer to a serene space where we are encouraged to breathe and to reconnect with the simple beauty of these objects.

Laurie Tennent, Ranunculus, 48 x 69, Polychrome on Aluminum, 2013