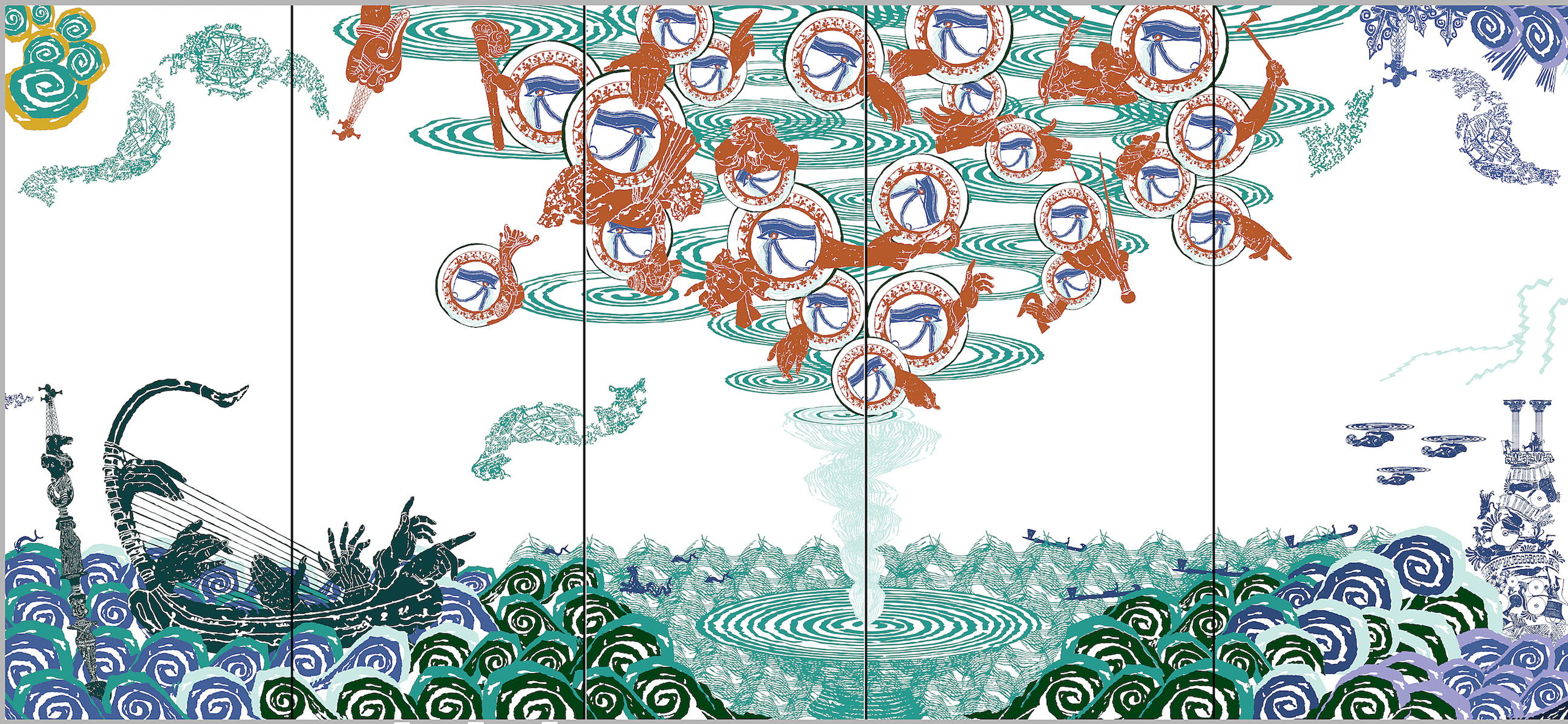

Digital study for Cosmogonic Tattoos Installation at UMMA and the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology

Jim Cogswell, Digital study for Cosmogonic Tattoos, 2016. Courtesy of the artist

The images that comprise Jim Cogswell’s frieze-like mural Cosmogonic Tattoos are lyrical, fanciful, and, at times, utterly bewildering. Anthropomorphic Greek amphoras sprout legs and scurry about. A hybrid harp/boat ferries its unusual passengers – expressive, personified hands— across surging waves. And ancient-looking architectural structures rise and collapse in post-apocalyptic ruins.

Occasioned by the University of Michigan’s bicentennial, the university commissioned artist Jim Cogswell to create a set of murals celebrating the holdings of the University of Michigan Museum of Art (UMMA) and the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology. Cogswell’s mural speaks to material exchange across cultures and the necessarily distorted histories and narratives that shape when artifacts are taken out of context and placed behind glass in museum environments. It’s an ambitious and highly conceptual cycle that manages to be both playful and cerebral.

“Cosmogonies,” Cogswell explains, “are our explanations for how our world came to be.”[i] His idea of a cosmogonic tattoo is sourced in the character Queequeg in Moby Dick, who bore a tattoo on his back depicting “a complete theory of the heavens and the earth, and a mystical treatise on the art of attaining truth.”[ii] For this site-specific installation, Cogswell created hundreds of vinyl images based on his paintings of 250 objects from the holdings of the Kelsey and UMMA. Affixing them to the expansive horizontally-oriented first-floor windows of each museum, he created a frieze of images which tell an ambitiously sweeping narrative addressing the migrations of ideas, artifacts, and people.

The narrative begins on the windows of the Frankel Family Wing at the UMMA. A ship full of anthropomorphic hands (derived from paintings within the UMMA), sail across a sea in a boat toward a promontory, only to endure a series of apocalyptic natural disasters. Taking what few cultural artifacts they can carry, these travelers embark on foot to find a new home. By design, the narrative breaks, and viewers must cross State Street and traverse a block north to view the rest of the mural at the Kelsey.

Jim Cogswell, Boats and Hands, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist

Here, we see more figures on migratory journeys. Architectural structures on promontories are erected, only to be destroyed by natural forces and invasion. The figures, always on the move, carry more cultural artifacts with them, and they themselves even metamorphose into complex mash-ups of disparate elements borrowed from multiple cultures: a Roman female torso sports the head of a goose derived from a Greek wine jug, for example. The narrative is like a obius strip, and ends with migrants on the move. Cogswell didn’t conceive of the Kelsey as a destination, but rather a “roundabout,” ultimately channeling the narrative—and the viewer—back toward the UMMA.

Every character, prop, and setting in this unfolding drama comes directly from Cogswell’s digital renderings of his paintings of artifacts at the Kelsey and the UMMA. But, like Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel, Cogswell’s images synthesize disparate elements from vastly different sources. A Greek kylix becomes the satellite dish on a radio tower, for example, and the radiating concentric rings of an Egyptian necklace becomes its transmission signals. Greek amphoras sprout wings derived from decorative Roman architectural elements. The seemingly random combination of elements calculatedly speaks to the mutability of cultural artifacts and their subjective meanings.

Jim Cosgwell, Study for Cosmogonic Tattoos, Working on site, Image courtesy of the Levi Stroud

While this sprawling horizontal collage of images seem utterly haptic, every element of the mural was impressively thought-out. For example, a rendering of Greek portrait bust from Cyprus is wittily placed on a window pane right behind the actual portrait bust itself. Like Cogswell’s own mash-ups, the bust reflects visual elements from multiple cultures (Greek and Egyptian), and even obliquely addresses migration: while the Mycenean culture declined, refugees from the mainland settled in Cyprus.

Jim Cogswell, Study for Cosmogonic Tattoos, Working on site, Image courtesy of the Levi Stroud

Cosmogonic Tattoos worthily aims to make us consider the histories of objects across space and time, and their ever-changing meanings. The British Museum’s Elgin Marbles, as a case in point, would certainly carry different associations for visitors from London than visitors from Athens. And these contemporary associations would contrast vastly from the pride and patriotism that an ancient Athenian would have felt, gazing on the same marbles in situ, wrapping, as they once did, around the Parthenon. Furthermore, America’s current changing views toward monuments to the Confederacy suggests that such change can occur even within a culture, and rapidly at that.

Admittedly, Cogswell’s mural cycle, while certainly visually engaging, might be prohibitively cryptic to anyone unfamiliar with the artist’s statement of intent and the helpful explanatory essays in the exhibition catalog (itself nicely produced and beautifully illustrated). But perhaps there’s a certain poetry to that, as it rather nicely underscores Cogswell’s metanarrative concerning the mutability of images and their meanings.

Jim Cogswell, Woman Duck, Study for Cosmogonic Tattoos, 2016, shellac ink and graphite on mylar. Image courtesy of the artist

[i] Cogswell, Jim, et al. Jim Cogswell : Cosmogonic Tattoos. University of Michigan, 2017.

University of Michigan Art Museum