No Boundaries, Installation Image – All Images Courtesy of Ron Scott

As part of a national tour, No Boundaries opened at the Charles Wright Museum of African American History on January 18, 2016. The exhibition represents nine aboriginal artists from the continent of Australia who were inspired by their ancient cultural traditions. The contemporary exhibition incorporates more than 75 paintings created between 1992 and 2012. The works are drawn from the collection of Debra and Dennis Scholl, Miami-based collectors and philanthropists.

“The artists all have a common thread, and each had reached a senior status in their communities.” said Dennis Scholl. “We chose works by those who, to paraphrase the artist Paddy Bedford, after having painted all of their mother ‘country’, and finally chose to simply paint.”

The indigenous aboriginal art of Australia has a rich history that has been studied by scholars from all parts of the world, especially the work that pre-dates the European colonization. The oldest forms are the paintings on rock in Central Australia that depict people, animals, plant life and spirituality. It is believed that Aboriginal people are the descendants of a single migration from Africa to the continent 64,000 to 75,000 years ago. All the artifacts and the earliest human remains suggest that the region now referred to as Queensland, was the single most densely populated area of pre-colonialized Australia. But this exhibition is about contemporary Aboriginal art that, according to some artists, is tied to their past.

Paddy Bedford, 70 X 64 Polymer on Canvas

Paddy Bedford comes from Jurrawun, Australia and spoke the Gila language. His work was integral to the development of the landmark exhibition, “Blood on the Spinifex” that was held at the Ian Potter Museum at the University of Melbourne in 2002. In his artwork, he introduced a new expressionism, one that recognized the use of both positive and negative space and stark contrast. He rose to national acclaim when his images brought to memory the station massacres, because to some, they symbolized aerial maps. Paddy Bedford’s work is held in collections throughout Australia, Europe and the United States.

Boxer Milner Tjampitijin, 40 X 32, Polymer on Canvas

Boxer Milner began painting in the 1980s at the Warlayirti Art Center in the Wirrimanku Balgo region. Buried in his palette and restricted formal syntax is his mastery of geometry and form. These rigid structures with high-keyed colored geometric shapes offer a rare idiosyncratic iconography not seen in other aboriginal art. Rendered in a measured architecture of lines and dots, they move into a more sophisticated sense of design. His work is part of many collections throughout Australia and at the National Gallery of Victoria.

Tommy Mitchel, 36 X 36, Polymer on Canvas

Born in the Gibson Desert near Papulankutja, Tommy Mitchel came to painting late in life. His glowing fields of overlapping dots create a patchwork of grids. Mitchel was quickly recognized as a regional talent at the Warakurna Art Centre. His graceful use of color and space take the viewer on a visual journey. He has described his work as drawing on his early life in the Ngaanyatjarra Country where he wandered as a child. His work is part of many collections, including the National Gallery of Victoria and the Art Gallery of South Wales.

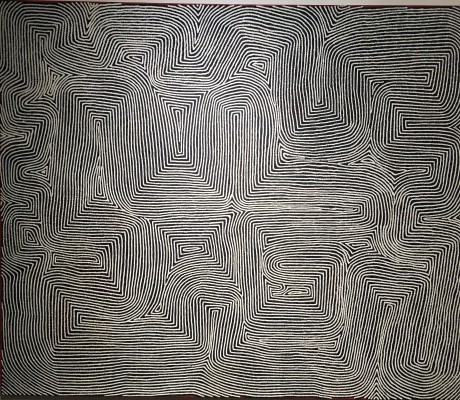

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, 66 X 70, Polymer on Canvas

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri is originally from Lake MacKay but lived nomadically with his family in the remote western desert. He eventually settled in to paint at the Papunya Tula Art Centre. His swirling lines of dots create a pulsating field of optical intensity. Shimmering like a mirage, they invoke a shifting of movement in the desert sand, a metaphor for the energy fields while ‘Dreaming’ that runs through everything. His work is part of many collections in Australia, including the National Gallery of Australia.

There is a wall of introductory information presented in the exhibition that includes biographies of each artist. The material introduces the term ‘Dreaming’ which occurs while the artist is awake or sleep. “For the artists in this exhibition, the Dreaming goes by different names: Tjukurrpa in the Western Desert; Ngarranggarni in the Kimberley; and Derulo in the North. The Dreaming incorporates ancestral beings, the creation of the universe and the laws governing social and religious behavior. It also dictates connections to a place that define individual Aboriginal identities. The Dreaming encodes the location of essential waterholes and food sources into stories, dances, and song.”

There is a short video as part of the exhibition, which is narrated by an art gallery owner. The cut-away shots of aboriginal people show them with little clothing and often sitting on the ground painting their dots. It caused this writer to research the history of the Aboriginal people of Australia which uncovered concerns raised by a United Nations report about unethical and discriminatory practices against Aboriginal indigenous people. Australia’s 460,000 Aborigines make up about 2 per cent of the population. They suffer higher rates of unemployment, substance abuse, and domestic violence than other Australians and have an average life expectancy of 17 years less than the rest of the country.

What would be educational in this exhibition is a section that places these artists in context to the overall treatment of these native indigenous people, their heritage, cultural, traditions, and challenges in a land that was colonized by Western Europeans in the mid-1700s. I am sure this kind of national show has been vetted and follows ethical standards for procurement by the collectors. Overall, the exhibition is a very good introduction to this contemporary art movement created by a native people whose art deserves recognition around the world.

This exhibit is free with museum admission. No Boundaries: Aboriginal Australian Contemporary Abstract Painting originated at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno, Nevada and was organized by William Fox, Director, Center for Art and Environment, and scholar Henry Skerritt.