Installation, Jaume Plensa’s Sculpture, Toledo Museum of Art

Spanish-born sculptor Jaume Plensa is perhaps best known in the United States for his permanent Crown Fountain installation in Millennium Park in Chicago. This sculpture, which projects recorded footage of the faces of dozens of Chicago citizens into 50-foot towers that flank the fountain, distills Plensa’s abiding interest – the maximizing of human forms to the scale of landscapes. Human Landscape , a quasi-retrospective of Plensa’s recent work has just opened at the Toledo Museum of Art, and features a selection of his arresting sculptures, six exterior works sited on the grounds surrounding the museum, and an array of his lesser-known works on paper. The cumulative effect is an exercise in gazing, quite literally, into the face of humanity.

James Plensa, Paula, 2013, Bronze

Plensa’s use of scale is nearly enough on its own to inspire awe, casting and carving sculptural neck-up portraits that stand at or above human size. Driving by the museum’s front entrance, one’s gaze is drawn by Paula (2013), a portrait of a young girl from the neck up, rendered in blackened bronze and standing out like an Easter Island head amidst the lush surrounding greenery. Around the museum’s eastern wing another piece, The Heart of Trees (2007) is sited, with 1:1 scale bronze-cast figures sitting in silent meditation at the base of seven live Kentucky Coffee trees, planted into a grove against the hillside and perfectly complimented by the angled verdigris exterior of the Center for Visual Arts. Those driving along Monroe Street by night might find their attention drawn by pieces on the grounds surrounding the Glass Pavilion, two torso pieces – Thoughts (2013) and Silent Music (II) (2013) – and two seated figures, Soul of Words, which are illuminated at night, to emphasize the open weave of their intricate metal work.

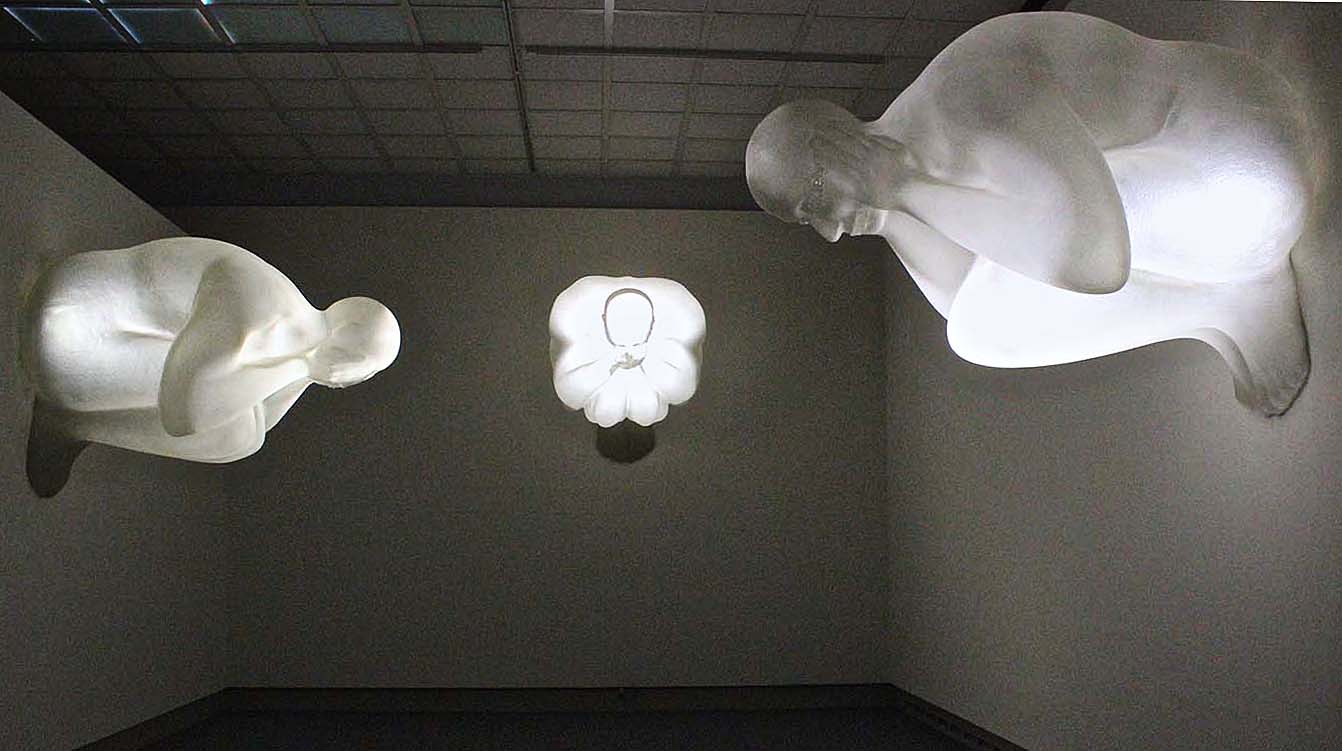

Jaume Plensa, See No Evil, Hear No Evil, Speak No Evil, 2010, Polyester resin, stainless steel, and LED light, dimensions variable

A figure seated with knees drawn up is a recurring motif for Plensa – at human scale, with The Heart of Trees; at maxi-scale, with Soul of Words; cast in hollow polyester resin, illuminated and mounted on the wall, in an interior trio of works, See No Evil, Hear No Evil, Speak No Evil (2010). This posture, and the tendency for his massive portrait faces to have their eyes closed, suggests that his figures have an interior landscape, as well as the physical one created or augmented by their presence. There is a kind of vulnerability to Paula, even as she towers far above human height, in her closed eyes and solemn expression.

Jaume Plensa, The Heart of Trees, 2007, Bronze (7 elements), Kentucky Coffee trees, 99 x 66 x 99 (each)

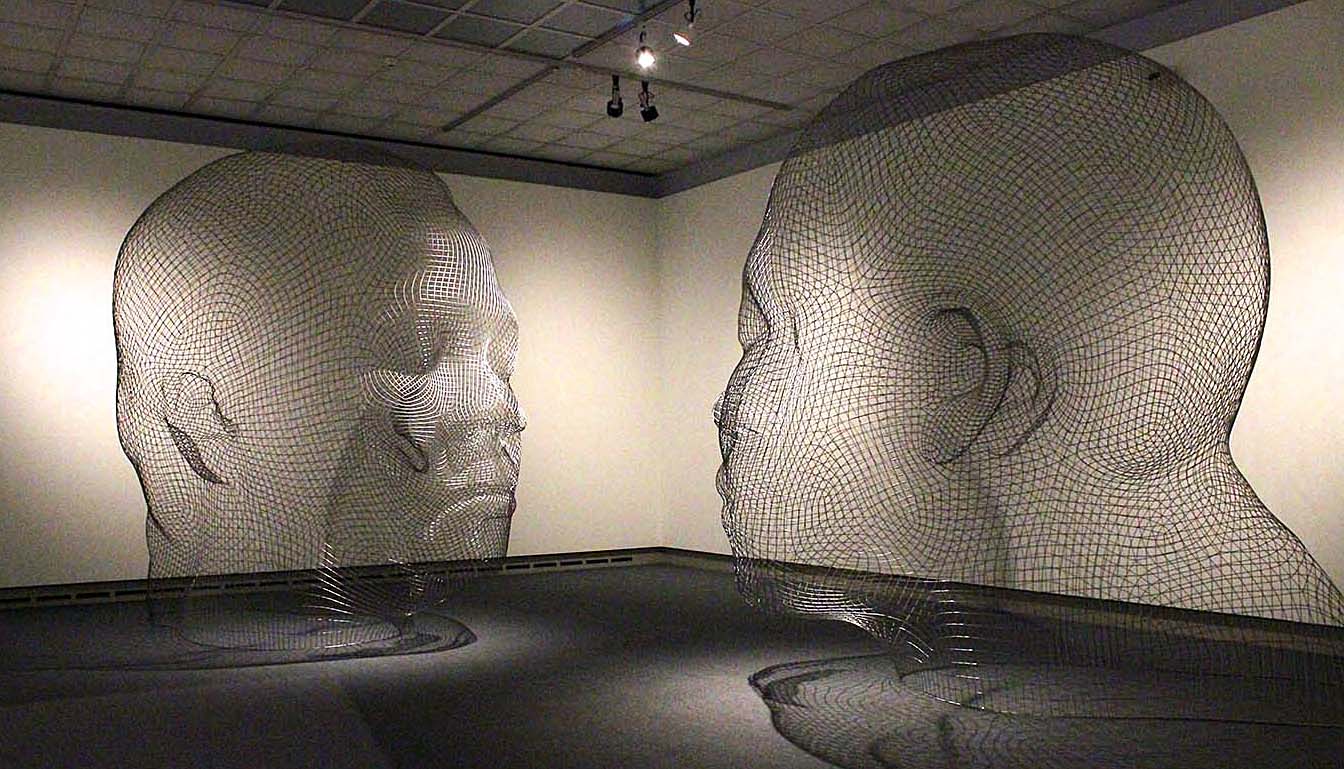

Though Plensa clearly delights in siting his works in open public spaces, the gallery works create all kinds of tableaus, as well. From either of two entry points to the exhibition, the viewer is greeted by a marble portrait head of what appears to be the same woman, Rui Rui (Plensa seems prone to reiterate subjects). Like Paula, Plensa’s head portraits feature an oddly squashed perspective that causes their appearance to shift as one walks around them. What appears to be in correct proportion from one angle becomes slightly or markedly off-kilter from another. The right-hand Rui Rui stands before two massive wire-frame heads in a peaceful sort of face-off in the corner. Images on paper line the walls – it is almost jarring to see subjects with fully articulated features and open eyes after all the smooth lines of Plensa’s abstractions. A curtain of iron letters, Silent Rain (2003), divides this smaller gallery from the main gallery with an ephemeral cascade of language – another of Plensa’s recurring themes.

Jaume Plensa, – Awilda & Irma, 2014, Stainless Steel, 400 x 400 x 300 cm (each

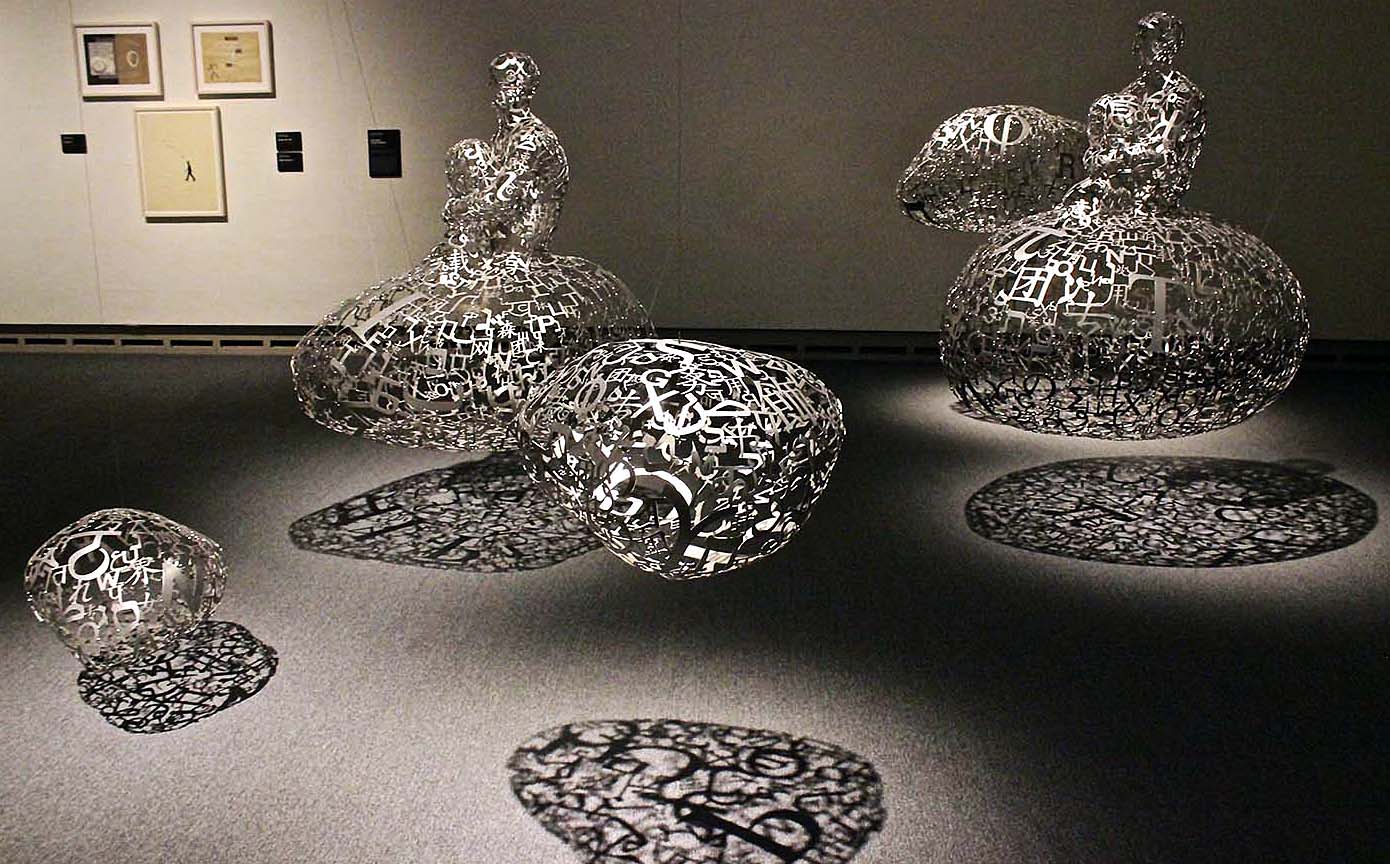

This focus on multi-lingual creations – some of which contain characters from eight different languages – suggests a keen desire on the part of the artist to find ways of bridging gaps in communication, or at least highlighting language barriers as a critical boundary between human societies. Through works like Silent Music, Thoughts, and The Heart of Trees, Plensa seems to suggest that music might provide a form of more universal connection; other works, like the Evil trio, highlight isolating factors such as anxiety, insomnia, and amnesia.

Jaume Plensa, Talking Continents (III), 2014, Stainless steel, dimensions variable

As any portrait photographer can tell you, people love to look at other people. There is a kind of perpetual enchantment with ourselves as subjects, and Plensa’s works play easily into this appeal, while subtly introducing themes of diversity, awareness, and connection – all buoyed by whimsical and unexpected touches. Floating in the main gallery, Talking Continents (III) (2014) features an archipelago of cloud-like forms, a couple of which are ridden by his ubiquitous seated figures. The effect is playful and magic-carpet-like; the seeming effortless lift of the metal forms belies their material structure, and their open motif of linguistic characters throws lacy shadows beneath them. All of Plensa’s environments, expertly installed around Toledo Museum of Art, provide opportunities to pause and wonder at the human condition – arguably one of life’s greatest mysteries, and the one given to all of us, as humans, to contemplate.

Jaume Plensa: Human Landscape, Toledo Museum of Art

June 17-Nov. 6, 2016