Whitney Museum of Art, Exterior, 2017 Courtesy of WMA by Ed Leaderman

The Whitney Biennial draws to a close, but not without a review from Detroit that showcases artists with roots in Metro Detroit.

Moving downtown into the Renzo -Piano- designed building on New York City’s Gansevoort Street delayed the 2017 Whitney Biennial a year, but it was worth the wait, as the spacious and beautiful new museum sits high just off the Hudson River overlooking the Highline Park and Chelsea art community. Organized by Christopher Y. Lew, the Whitney’s associate curator, and Mia Locks, an independent curator, the exhibition highlights work by sixty-three individuals and collective’s artist works from all parts of the United States. The diversity of artists and media is staggering when considering the large demographic of contemporary art that is represented.

I was mostly surprised by how much space was committed to each artist, where entire rooms with 5 to -7 pieces of work were on display by each artist. It speaks to the size and space the new museum provides, luring an art-world audience, as the selections confront edgy social issues in the American culture.

Maya Stovall, Liquor Store Theatre, Video Performance, 2016

As promised, let’s start with Detroit. The videos of post-minimalist ballerina Maya Stovall are front and center as she offers her art from the sidewalks of Detroit illustrating modern dance working with collaborators Biba Bell, Mohamed Soumah, and Todd Stovall, she presents the motivations, genealogies, and sources of her Liquor Store Theater.

She says in her statement, “I am an artist interested in monumental questions of human existence. I am interested in place and space, cities, power, and the affect and desire of the day-to-day in people’s lives. I approach monumental questions of human existence with up close rigor. My work is steeped in philosophy, theory, and resonates with my way of being in the world.” The video screens and audio-fed headphones document a series of dance performances from the streets of Detroit. Stovall pays respectful homage to the cultural traditions in the Detroit black community as commercial developers swirl rapidly to gentrify the city.

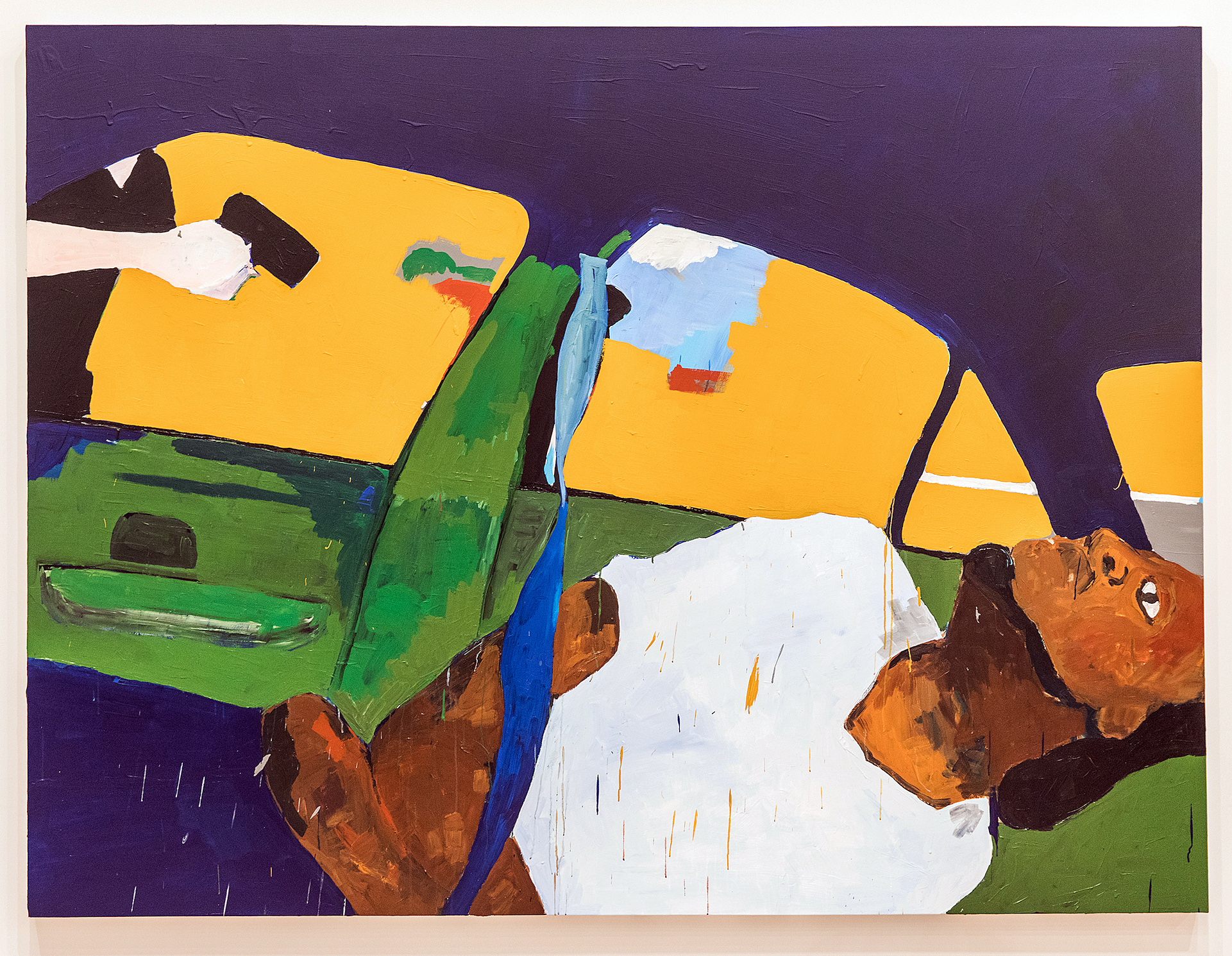

Dana Schutz, Elevator, 2017. Oil on canvas, 144 x 180″

The artist Dana Schultz grew up in Livonia, attended High School at the Adlai Stevenson High School, and went on to obtain her BFA from the Cleveland Institute of Art, and an MFA from Columbia University. As the elevator opens on the fifth floor of the Biennial, the viewer is immediately confronted with a large figurative oil painting, Elevator, which displays a kind of chaos occurring in the transitional space between two elevator doors, perhaps either opening or closing. There is an abstract, even cubist feeling to this colorful figure painting, depicting struggle and larger-than-life insects, adding to the feeling of anxiety, even fear. It took me a moment to understand why there were these two side panels attached to the work, until I read the title.

Dana Schutz, Open Casket, 2016. Oil on canvas, 40 x 56″

Schutz’s work seems to draw on social environments, best illustrated in her 2016 painting, Open Casket, that depicts her version of the mutilated corpse of Emmett Till, a seminal event in the American civil rights movement. Controversy swirled around the work as exploitation, best described in The New Yorker by Calvin Tomkins:

In the current climate of political and racial unrest, Emmett Till seemed like a risky subject for a white artist to engage with. “I’ve wanted to do a painting for a while now, but I haven’t figured out how,” [Schultz] said. “It’s a real event, and it’s violence. But it has to be tender, and also about how it’s been for his mother. I don’t know, I’m trying. I’m talking too much about it.” In a later conversation, [Schultz] said, “How do you make a painting about this and not have it just be about the grotesque? I was interested because it’s something that keeps on happening. I feel somehow that it’s an American image.”

Dana Shultz resides in New York City, works out of her studio in the Gowanus section of Brooklyn, and is represented by the Pretzel Gallery in New York City.

Carrie Moyer, Glimmer Glass, 2016. Acrylic and glitter on canvas, 96 x 78 in”

Another Detroit artist in the Biennial, now living in Brooklyn, NYC, is Carrie Moyer, who received a BFA from Pratt Institute in 1985, and an MFA from the Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts at Bard College in 2001. In an interview with Jennifer Samet for Hyperallergic, she says, “I was born in Detroit, where my family has longstanding roots. My grandfather was a policeman during the Detroit riots in the 1960s. But I had countercultural parents who put us in a van when I was nine and drove us out to California with all of our belongings. My family lived all over the Northwest for the next ten years — California, Oregon, and Washington.”

In her large acrylic painting, Glimmer Glass, it is the overlay and transparency that compliments her distinctive use of form. The vibrant painting embraces visual pleasure with watery veils of florescent hues, often mixed with glitter. The artist explains, “I’m interested in abstract painting that is experienced both visually and physically. The forms are constantly shifting from the familiar to the strange in a way that seems to escape words.”

Carrie Moyer, Candy Cap , 2016. Acrylic and glitter on canvas, 72 x 96″

With her beginning in graphic design, Carrie Moyer has been a force in abstract painting since 2000 with a strong familiarity with the language of Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism; she draws on influences like Georgia O’Keeffe and Elizabeth Murray. I was struck by the work, Candy Cap, where she depends heavily on a feminine composition of flower and organic shapes to form this work using acrylic transparency, glitter, and Flashe on canvas. Moyer is a Professor in the Art and Art History Department at Hunter College, where she is the Director of the Graduate Program. Moyer is represented by DC Moore Gallery.

Samara Golden, The Meat Grinder’s Iron Clothes, 2017. (Installation, 5th floor West Gallery). Insulation foamboard, extruded polystryrene, epoxy resin, carpet, vinyl, fabric, acrylic paint, spray paint, nail polish, plastic, altered found objects and mirror.

The artist Samara Golden was born in Ann Arbor, Michigan in 1973, and received her BFA from Minneapolis College of Art & Design, and an MFA from Columbia University in 2009. She is an installation artist based in Los Angles, CA where her work often includes a combination of sculpture, video, and sound. Her first solo exhibition was The Flat Side of the Knife and was organized by Mia Locks at the Museum of Modern Art PS1. Golden’s work in the Biennial, The Meat Grinder’s Iron Clothes, feels like a dystopian environment overlooking the Hudson River that contrasts office and domestic spaces. Admittedly, this writer has limited skill in describing the aesthetic aspects of this work of mirrors, living rooms, and wheelchairs.

Henry Taylor, “THE TIMES THAY AINT A CHANGING, FAST ENOUGH! (2017), acrylic on canvas, 72 x 96″

There are sixty-three artists represented in the Whitney Biennial, and this review has had Metro Detroit artists as its focus, but I would like to mention another artist, Henry Taylor, living and working out of Los Angeles, CA. With a BFA from California Institute for the Arts and a variety of life experience, Taylor has created a body of work that has a critical social sensibility that confronts the racial tension between law enforcement and the community they serve. In his work, The Times They Ain’t A Changing, Fast Enough! drawn from video, captures the moments after Philando Castile had been fatally shot by a police officer. Aside from the social message, I am drawn to the composition and naïve style in which Taylor executes his unaffected imagery. His empathetic style may draw on his ten years of working at the Camarillo State Mental Hospital near Santa Barbara, CA. Taylor’s work is represented by Blum & Poe in Los Angles, CA.

Aliza Nisenbaum (b. 1977), La Talaverita, Sunday Morning NY Times, 2016. Oil on linen, 68 x 88″

It could be that because this writer is also a painter, the work in the Biennial by Aliza Nisenbaum is immensely attractive. Known for depicting undocumented immigrants, there is something in the work La Talaverita, Sunday Morning NY Times, that combines working from live models, an elevated camera angle, and the casually colorful subject that connects with so many people. Born in Mexico City, Nisenbaum earned a BFA and MFA from the Chicago Art Institute. She says in her statement, “My work has repeatedly reflected on ideas of empathy or pathways for exchange between different people. My status as a legal American citizen makes me one of the few and privileged immigrants from my home country. Whether working with abstraction or, more recently, with still life and portraiture, I have tried to make paintings that support the experience of looking closer and with greater intention. My current body of work makes this connection explicit in its focus on the human face, which the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas suggests is inherently an ethical call to greater human justice.”

For me, her work personalizes the immigrant experience and could easily reflect the life in South West Detroit.

The new Whitney Museum of Art in its new location demonstrates in the curation of it’s 2017 Biennial a refreshing supply of under-recognized artists with diverse perspectives from all parts of the United States, and places itself at the center of American contemporary art.