In 1966, Andy Warhol was churning out silkscreens of electric chairs and car accidents, the Fluxus movement had given the world zany performances by the likes of Joseph Beuys and Yoko Ono, and Lichtenstein’s punchy Whams! and Bams!sprawled across gallery walls by the yard. Against this cacophonic backdrop, when Michel Parmentier debuted his understated, monochromatic canvasses of painted blue stripes, they might hardly seem particularly radical, yet “radical” is precisely how Parmentier’s work is often described.

Through October, Michigan State University’s Broad Art Museum allocates its whole second floor to exploring just what might be so groundbreaking about Parmentier’s work. The exhibition brings together 30 representative works spanning the artist’s career, along with rare texts authored by the artist. These allusive minimalist canvasses reveal the consistency of the artist’s philosophy, which remained largely unchanged from his early experiments in the 60s to the works he created just prior to his passing in 2000.

Michel Parmentier, installation view at the MSU Broad, 2018. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography

Parmentier didn’t want his painting to be about anything other than the physicality of paint itself, so he abandoned subject matter. His work was guided by an almost religious adherence to the pliagemethod, for which he prepared a large un-stretched canvass by folding it like an accordion in increments of 38 centimeters. He’d then spray-paint the exposed surface, unfolding it to reveal visceral horizontal creases and painted bars in monochromatic, horizontal blue stripes. The creative act was thus reduced to a nearly-mechanical process.

At first, his works might seem to rhyme with the striped paintings of Anges Martin. But Martin’s chromatically subtle works are warm, nuanced, and serene, while Parmentier’s have the impersonal detachment of an improvised painted banner advertisement. He worked in only one color each year. Wishing to disassociate his bars of color from any implied symbolism or personal significance, he’d change the color annually, switching from blue to gray in 1967, and finally to red in 1968.

Michel Parmentier, installation view at the MSU Broad, 2018. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography

Parmentier joined forces with several other French painters (Buren, Mosset, and Toroni, collectively calling themselves BMPT), but broke from the group in 1967, perhaps believing the other artists were becoming too reactionary.[i] In 1968, he stopped painting altogether, not producing any art again for fifteen years.

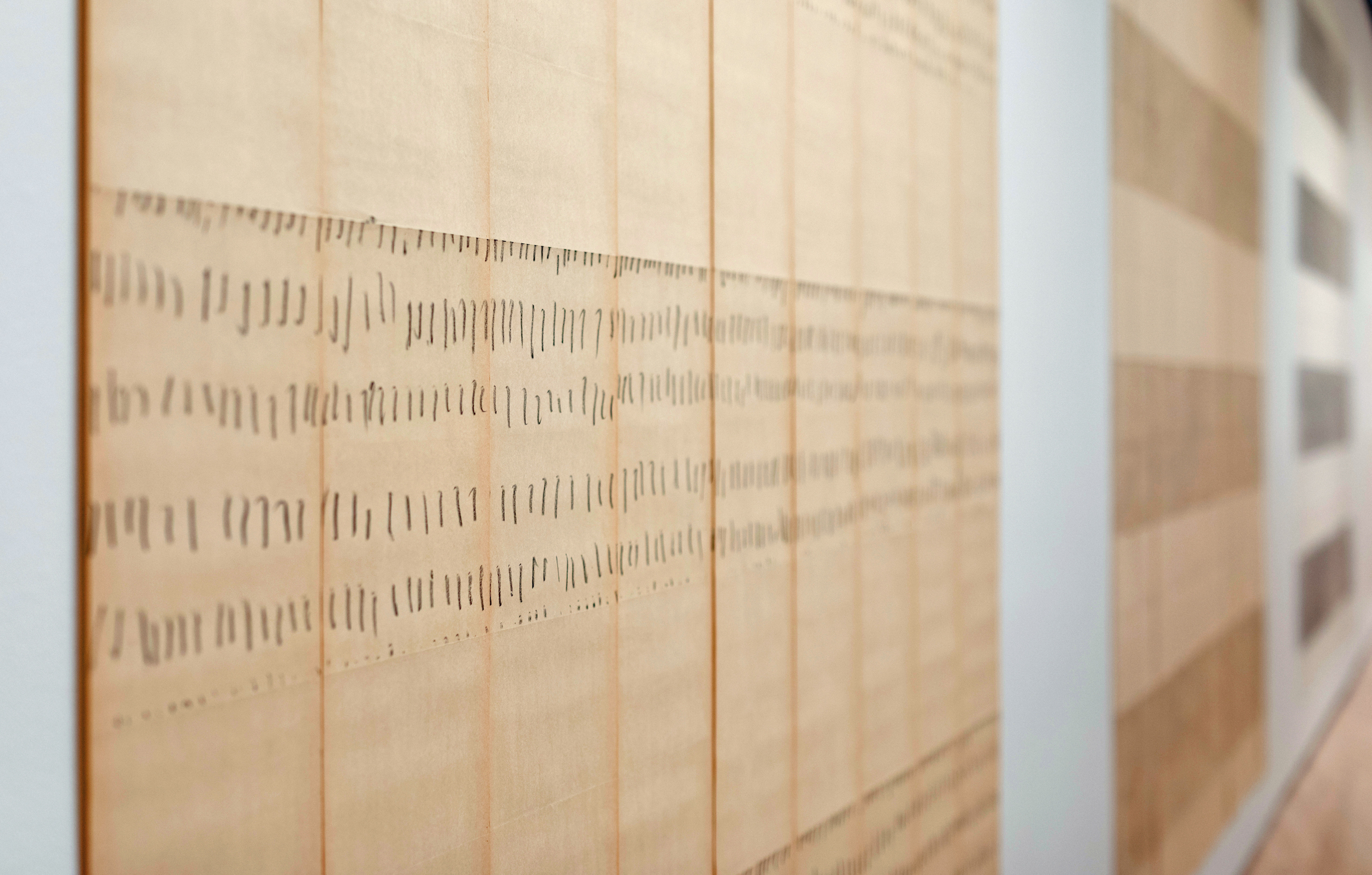

When he resumed in 1983, he integrated some variety in texture and media. Color disappeared altogether, replaced with varying values of graphite-gray or barely-discernible, creamy white. And in place of canvass, Parmentier began stapling together individual sheets of disconcertingly cheap printing paper. In addition to paint, he explored pastel, charcoal, and pencil. We even see trace elements of the artist’s hand start to emerge: rather than apply paint with a spray can, Parmentier took to scrubbing in his horizontal stripes with pastel, or applying thousands of neatly-arranged horizontal graphite marks. But his later works never strayed far from that which he produced the 60s. They invariably retained the same folded horizontal creases at 38cm increments, and they defiantly refused to be anything other than self-referential.

Michel Parmentier, installation view at the MSU Broad, 2018. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography

The Broad Art Museum’s retrospective compartmentalizes the artist’s work chronologically, beginning with his earliest blue, gray, and red paintings from the 60s. As the artist intended, they’re unframed and affixed to the wall only at the top, making his paintings almost look like linens hanging up to dry. An adjacent gallery displays a large selection of the artist’s writings and projects a one-channel video showing the artist preparing a canvass using his signature pliagemethod, giving us a sense of the mechanical rigidity of his working process.

A third gallery space is devoted to his later works, generally consisting of many sheets of paper affixed together, marked with graphite or pastel. Here, viewers can see elements that get lost in translation when his work is reproduced in photos. Easily missable (even in person) are the dates he’d stamp repeatedly on the hem of each work; if a piece took him several days, we’ll see several dates, each stamped on the relevant section of the image. It’s an element that recalls the conceptual paintings of On Karowa, who famously produced paintings of the day’s date, always painted in white against a black background.

Michel Parmentier, installation view at the MSU Broad, 2018. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography

In a letter to a friend, Parmentier once wrote, “To work without producing is undoubtedly one of the finest ideas there is […], not to work at all is another. Detachment from everything is a third. Being interested in everything without actively drawing any conclusions—simply doing, rather—seems to me very good.”[ii]It’s a philosophy which certainly informed his work, which always remained intentionally disengaged and aloof. So it’s to the Broad’s credit that it took a chance on organizing an exhibition exploring such an esoteric artist. And while this may lack the punchy visual theatrics of some of the Broad’s previous shows, it carries some historic weight as the artists’ first ever retrospective in the United States. Furthermore, one really does need to see Parmentier’s oveurein its entirety to grasp the unflinching consistency of his desire to produce art which, as one critic intoned in 1967, “simply exists.”

Michel Parmentier @ MSU Broad Museum through October 7, 2018

Leave a Reply