Charles Pollock: Modernism in the Making, installation view at the MSU Broad, 2018. Image: Eat Pomegranate Photography

We all know of Pollock, the aspirant artist who studied under Thomas Hart Benton in New York, gained experience painting murals commissioned by the depression-era Works Progress Administration, and became an acclaimed Abstract Expressionist.Or do we? After all, most of us are likely more familiar with his younger sibling, Jackson, who also studied under Benton in New York, also made paintings for the WPA, and also worked in Abstract Expressionism, following the course laid by his older brother, Charles.

Through December, Michigan State University celebrates the work and legacy of Charles Pollock, who taught at MSU for almost 30 years (1942-1969) and retired 50 years ago. Charles worked in abstraction, though unlike his brother, his work bends more toward color-field painting, occasionally evoking the misty canvasses of Mark Rothko. Pollock was well connected with the driving artists and personalities of the postwar New York School, and he used his connections to acquire works of art and bring artists of America’s avant-gardeto campus. Along with the paintings, drawings, and correspondence of Charles Pollock himself, this intimate one-room exhibition also offers a cross-section of the many artists and personalities that encompassed his broad social circle.

Before turning toward abstraction, his early work carried thick Social Realist accent. Somber lithographs like After the Drought, portraying an eerily smiling cattle skull set against a bleak and unpeopled desert-scape, could easily serve as concept art for a film adaptation of a Steinbeck novel. Similarly, his Man at the Well (1933) is hardly an optimistic portrayal of America as the land of opportunity; the empty bucket and the grim expression the on figure’s face together imply that this well has run dry. Pollock also worked in graphic design, and it’s no surprise to see that he made the cover for an anthology of William Falkner, whose Sound and Fury viscerally gave the lie to the notion that America was a new-world Arcadia.

Pollock came to Michigan while working for the Works Progress Administration, and it was a set of mural assignments for the Lansing Water Treatment Plant and Michigan State University’s Fairchild Auditorium that brought him to Lansing. Here, viewers can see an early sketch for his Fairchild mural; the completed work, conceived as a triptych, is still on view in the Auditorium. The heroic imagery reveals the influence of Benton; implausibly muscular workers go about the business of making America great though brawn, brain, industry, and resourcefulness.

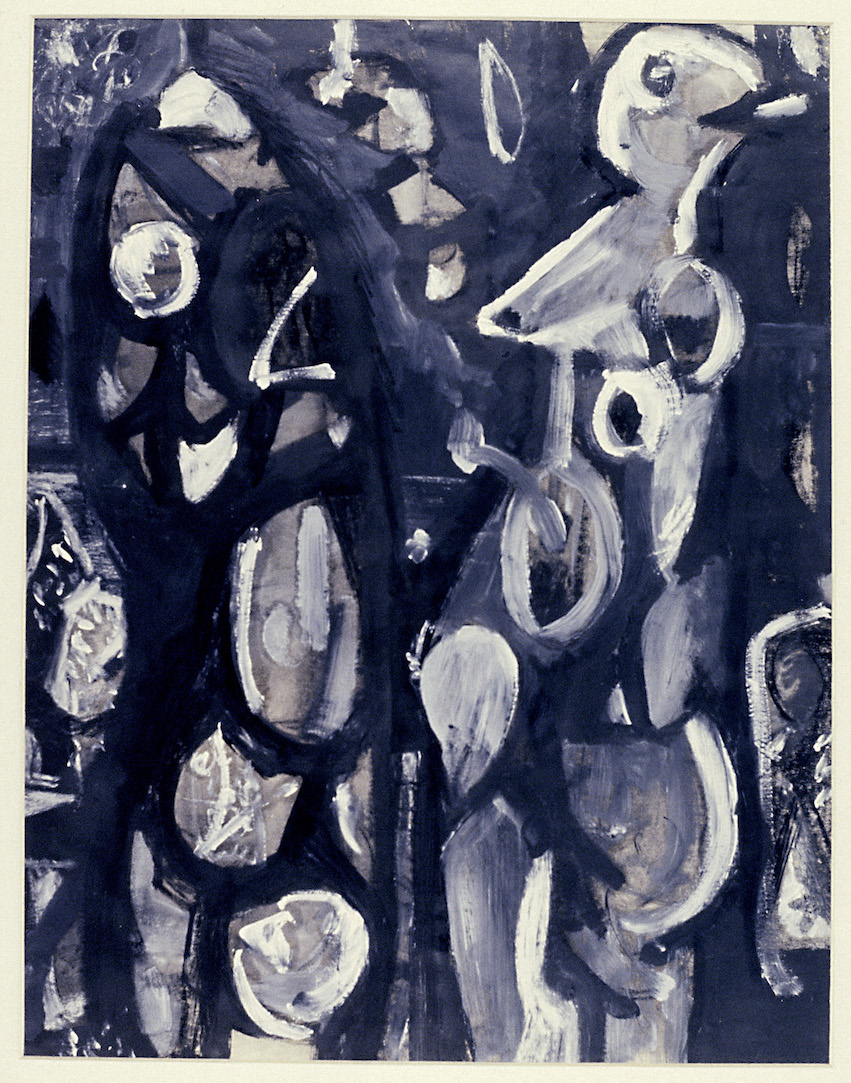

Charles Pollock, #95, 1967. Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum, Michigan State University, gift of George F. Schwelinger in memory of Ella Schwelinger.

In the 1940s, Pollock turned toward abstraction. Unlike Jackson, whose splashy drip-paintings seemed to suggest a haptic attitude of devil-may-care spontaneity, Charles’ paintings are, by comparison, orderly and restrained. His #86 fills the canvass with a grid of vertically oriented rectilinear color swatches, recalling the vertically-oriented color field paintings of Barnett Newman. And his #95 similarly offers viewers a serene grid of color fields, whose soft borders are suggestive of the color-field paintings of Rothko.

But the lion’s share of the gallery space highlights the artist’s connections with Abstract Expressionism’s famous personalities, many of whom he brought to Michigan State. On view are photographs and correspondence which reveal the extent of his reach, such as an invitation to famed art-critic Clement Greenburg, who came to MSU to deliver a talk.

Helen Frankenthaler, Untitled, 1950. Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum, Michigan State University, gift of Clement Greenberg.

There is also an impressive selection of paintings and sculptures by names synonymous with the postwar American art scene: Kenneth Noland, Barnett Newman, Helen Frankenthaler, and others. With the exception of an untitled metallic sculpture by Italo Scanga, consciously evoking a reductive human face, all the works on view are rooted in pure abstraction. The earliest work in the show is an untitled thickly-impostoed painting by Helen Frankenthaler from 1950, created just when Abstract Expressionism was enjoying its meteoric ascent in New York. It’s scrubbed-in gestural tangle of circular forms shows the influence of Jackson Pollock, recalling some of his messily-painted figurative work prior to his development of drip painting. Frankenthaler become a driving force in the development of Color Field painting, influencing the likes of Kenneth Noland, represented here with a typically Noland-esque lozenge-shaped arrangement of concentric squares emerging from the center of a canvass.

Charles Pollock: Modernism in the Making, installation view at the MSU Broad, 2018. Image: Eat Pomegranate Photography

Modernism in the Making is a small exhibit, but it brings together an impressively muscular cross-section of A-list postwar artists, offering a snapshot portrayal of the emergence of Abstract Expressionism. Admittedly, it’s hard not to walk away just a touch disappointed that Charles never managed to procure for Michigan State a drip-painting by Jackson Pollock himself. Put perhaps it’s for the best; the other Pollock has received plenty of attention—too much, really– and Charles and his circle certainly deserve their moment in the spotlight.

Broad Museum Michigan State University

Charles Pollock, Modernism in the Making runs through December 30; more information can be found here.